The Implications of Pruritogens in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3628-3641-Pruritus in Selected Dermatoses

Eur opean Rev iew for Med ical and Pharmacol ogical Sci ences 2016; 20: 3628-3641 Pruritus in selected dermatoses K. OLEK-HRAB 1, M. HRAB 2, J. SZYFTER-HARRIS 1, Z. ADAMSKI 1 1Department of Dermatology, University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 2Department of Urology, University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland Abstract. – Pruritus is a natural defence mech - logical self-defence mechanism similar to other anism of the body and creates the scratch reflex skin sensations, such as touch, pain, vibration, as a defensive reaction to potentially dangerous cold or heat, enabling the protection of the skin environmental factors. Together with pain, pruritus from external factors. Pruritus is a frequent is a type of superficial sensory experience. Pruri - symptom associated with dermatoses and various tus is a symptom often experienced both in 1 healthy subjects and in those who have symptoms systemic diseases . Acute pruritus often develops of a disease. In dermatology, pruritus is a frequent simultaneously with urticarial symptoms or as an symptom associated with a number of dermatoses acute undesirable reaction to drugs. The treat - and is sometimes an auxiliary factor in the diag - ment of this form of pruritus is much easier. nostic process. Apart from histamine, the most The chronic pruritus that often develops in pa - popular pruritus mediators include tryptase, en - tients with cholestasis, kidney diseases or skin dothelins, substance P, bradykinin, prostaglandins diseases (e.g. atopic dermatitis) is often more dif - and acetylcholine. The group of atopic diseases is 2,3 characterized by the presence of very persistent ficult to treat . Persistent rubbing, scratching or pruritus. -

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.06.20055715; this version posted April 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 Mo%on Sifnos: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstra%ng the effec%veness of tradipitant in the treatment of mo%on sickness Vasilios M. Polymeropoulos*1, Mark É. Czeisler1#a, Mary M. Gibson1¶, Aus%n A. Anderson1¶, Jane Miglo1#b, Jingyuan Wang1, Changfu Xiao1, Christos M. Polymeropoulos1, Gunther Birznieks1, Mihael H. Polymeropoulos1 1 Vanda Pharmaceu%cals, Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America #a The Ins%tute for Breathing and Sleeping, Aus%n Health, Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia #b College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] (VMP) ¶These authors contributed equally to this work. NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.06.20055715; this version posted April 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 2 Abstract Background Novel therapies are needed for the treatment of mo%on sickness given the inadequate relief, and bothersome and dangerous adverse effects of currently approved therapies. -

Recent Advances in Drug Discovery of GPCR Allosteric Modulators

Recent Advances in Drug Discovery of GPCR Allosteric Modulators ADDEX Pharma S.A., Head of Core Chemistry Chemin Des Aulx 12, 1228 Plan-les-Ouates, Geneva, Switzerland Jean-Philippe Rocher, PhD results in a number of differentiating factors. In fact, most Introduction allosteric modulators have little or no effect on receptor function until the active site is bound by an orthosteric The importance of the allosteric regulation of cellular ligand. Allosteric modulators therefore have multiple functions has been known for decades and even the word potential advantages compared to small molecule and “allosterome,” which describes the endogenous alloste- biologic orthosteric drugs. In particular, they offer new ric regulator molecules of a cell, has been proposed 1. chemistry possibilities allowing access to well known tar- Although best described as modulators of enzymes, gets that have been considered intractable to historical advances in molecular biology and robotic HTS technolo- small molecule approaches. For example, allosteric mod- gies recently allowed the discovery of small molecule allo- ulators may soon be developed for targets which hereto- steric modulators of various biological systems, including fore have been only successfully targeted with proteins GPCR and non-GPCR targets. Today, allosteric modula- and peptides. In other words, allosteric drugs with all the tors appear to be an emerging class of orally available advantages of small molecules - brain penetration, eas- therapeutic agents that can offer a competitive advantage ier manufacturing, distribution and oral administration over classical “orthosteric” drugs. This potential stems - may soon be viewed as the best life cycle management from their ability to offer greater selectivity and differ- strategy for protein therapeutics 2. -

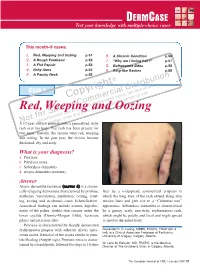

Red, Weeping and Oozing P.51 6

DERM CASE Test your knowledge with multiple-choice cases This month–9 cases: 1. Red, Weeping and Oozing p.51 6. A Chronic Condition p.56 2. A Rough Forehead p.52 7. “Why am I losing hair?” p.57 3. A Flat Papule p.53 8. Bothersome Bites p.58 4. Itchy Arms p.54 9. Ring-like Rashes p.59 5. A Patchy Neck p.55 on © buti t ri , h ist oad rig D wnl Case 1 y al n do p ci ca use o er sers nal C m d u rso m rise r pe o utho y fo C d. A cop or bite ngle Red, Weleepirnohig a sind Oozing a se p rint r S ed u nd p o oris w a t f uth , vie o Una lay AN12-year-old boy dpriesspents with a generalized, itchy rash over his body. The rash has been present for two years. Initially, the lesions were red, weeping and oozing. In the past year, the lesions became thickened, dry and scaly. What is your diagnosis? a. Psoriasis b. Pityriasis rosea c. Seborrheic dermatitis d. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) Answer Atopic dermatitis (eczema) (answer d) is a chroni - cally relapsing dermatosis characterized by pruritus, later by a widespread, symmetrical eruption in erythema, vesiculation, papulation, oozing, crust - which the long axes of the rash extend along skin ing, scaling and, in chronic cases, lichenification. tension lines and give rise to a “Christmas tree” Associated findings can include xerosis, hyperlin - appearance. Seborrheic dermatitis is characterized earity of the palms, double skin creases under the by a greasy, scaly, non-itchy, erythematous rash, lower eyelids (Dennie-Morgan folds), keratosis which might be patchy and focal and might spread pilaris and pityriasis alba. -

Apoptotic Threshold Is Lowered by P53 Transactivation of Caspase-6

Apoptotic threshold is lowered by p53 transactivation of caspase-6 Timothy K. MacLachlan*† and Wafik S. El-Deiry*‡§¶ʈ** *Laboratory of Molecular Oncology and Cell Cycle Regulation, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and Departments of ‡Medicine, §Genetics, ¶Pharmacology, and Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Communicated by Britton Chance, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, April 23, 2002 (received for review January 11, 2002) Little is known about how a cell’s apoptotic threshold is controlled Inhibition of the enzyme reduces the sensitivity conferred by after exposure to chemotherapy, although the p53 tumor suppres- overexpression of p53. These results identify a pathway by which sor has been implicated. We identified executioner caspase-6 as a p53 is able to accelerate the apoptosis cascade by loading the cell transcriptional target of p53. The mechanism involves DNA binding with cell death proteases so that when an apoptotic signal is by p53 to the third intron of the caspase-6 gene and transactiva- received, programmed cell death occurs rapidly. tion. A p53-dependent increase in procaspase-6 protein level al- lows for an increase in caspase-6 activity and caspase-6-specific Materials and Methods Lamin A cleavage in response to Adriamycin exposure. Specific Western Blotting and Antibodies. Immunoblotting was carried out by inhibition of caspase-6 blocks cell death in a manner that correlates using mouse anti-human p53 monoclonal (PAb1801; Oncogene), with caspase-6 mRNA induction by p53 and enhances long-term rabbit anti-human caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), mouse survival in response to a p53-mediated apoptotic signal. -

The Role of Caspase-2 in Regulating Cell Fate

cells Review The Role of Caspase-2 in Regulating Cell Fate Vasanthy Vigneswara and Zubair Ahmed * Neuroscience and Ophthalmology, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 April 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020; Published: 19 May 2020 Abstract: Caspase-2 is the most evolutionarily conserved member of the mammalian caspase family and has been implicated in both apoptotic and non-apoptotic signaling pathways, including tumor suppression, cell cycle regulation, and DNA repair. A myriad of signaling molecules is associated with the tight regulation of caspase-2 to mediate multiple cellular processes far beyond apoptotic cell death. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the literature pertaining to possible sophisticated molecular mechanisms underlying the multifaceted process of caspase-2 activation and to highlight its interplay between factors that promote or suppress apoptosis in a complicated regulatory network that determines the fate of a cell from its birth and throughout its life. Keywords: caspase-2; procaspase; apoptosis; splice variants; activation; intrinsic; extrinsic; neurons 1. Introduction Apoptosis, or programmed cell death (PCD), plays a pivotal role during embryonic development through to adulthood in multi-cellular organisms to eliminate excessive and potentially compromised cells under physiological conditions to maintain cellular homeostasis [1]. However, dysregulation of the apoptotic signaling pathway is implicated in a variety of pathological conditions. For example, excessive apoptosis can lead to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, whilst insufficient apoptosis results in cancer and autoimmune disorders [2,3]. Apoptosis is mediated by two well-known classical signaling pathways, namely the extrinsic or death receptor-dependent pathway and the intrinsic or mitochondria-dependent pathway. -

Caspase-1 Antibody A

Revision 1 C 0 2 - t Caspase-1 Antibody a e r o t S Orders: 877-616-CELL (2355) [email protected] Support: 877-678-TECH (8324) 5 2 Web: [email protected] 2 www.cellsignal.com 2 # 3 Trask Lane Danvers Massachusetts 01923 USA For Research Use Only. Not For Use In Diagnostic Procedures. Applications: Reactivity: Sensitivity: MW (kDa): Source: UniProt ID: Entrez-Gene Id: WB H Endogenous 20 p20. 30 to 45 Rabbit P29466 834 beta, delta, gamma. 50 alpha. Product Usage Information 3. Miura, M. et al. (1993) Cell 75, 653-60. 4. Kuida, K. et al. (1995) Science 267, 2000-3. Application Dilution 5. Li, P. et al. (1995) Cell 80, 401-11. 6. Feng, Q. et al. (2004) Genomics 84, 587-91. Western Blotting 1:1000 7. Martinon, F. et al. (2002) Mol Cell 10, 417-26. Storage Supplied in 10 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 100 µg/ml BSA and 50% glycerol. Store at –20°C. Do not aliquot the antibody. Specificity / Sensitivity Caspase-1 Antibody detects endogenous levels of pro-caspase-1 and the caspase-1 p20 subunit. The antibody is expected to detect alpha, beta, gamma and delta isoforms. Species Reactivity: Human Source / Purification Polyclonal antibodies are produced by immunizing animals with a synthetic peptide corresponding to residues within the p20 subunit of human caspase-1. Antibodies are purified by protein A and peptide affinity chromatography. Background Caspase-1, or interleukin-1ß converting enzyme (ICE/ICEα), is a class I cysteine protease, which also includes caspases -4, -5, -11, and -12. -

Frontiers in Dermatology and Venereology - a Series of Theme Issues in Relation to the 100-Year Anniversary of Actadv

ISSN 0001-5555 ActaDV Volume 100 2020 Theme issue ADVANCES IN DERMATOLOGY AND VENEREOLOGY A Non-profit International Journal for Interdisciplinary Skin Research, Clinical and Experimental Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases Frontiers in Dermatology and Venereology - A series of theme issues in relation to the 100-year anniversary of ActaDV Official Journal of - European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry Affiliated with - The International Forum for the Study of Itch Immediate Open Access Acta Dermato-Venereologica www.medicaljournals.se/adv ACTA DERMATO-VENEREOLOGICA The journal was founded in 1920 by Professor Johan Almkvist. Since 1969 ownership has been vested in the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica, a non-profit organization. Since 2006 the journal is published online, independently without a commercial publisher. (For further information please see the journal’s website https://www. medicaljournals.se/acta) ActaDV is a journal for clinical and experimental research in the field of dermatology and venereology and publishes high- quality papers in English dealing with new observations on basic dermatological and venereological research, as well as clinical investigations. Each volume also features a number of review articles in special areas, as well as Correspondence to the Editor to stimulate debate. New books are also reviewed. The journal has rapid publication times. Editor-in-Chief: Olle Larkö, MD, PhD, Gothenburg Former Editors: Johan Almkvist 1920–1935 Deputy Editors: Sven Hellerström 1935–1969 -

Dermatological Disorders in Tuvalu Between 2009 and 2012

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 12: 3629-3631, 2015 Dermatological disorders in Tuvalu between 2009 and 2012 LI-JUNG LAN1,2, YING-SHUANG LIEN2,3, SHAO-CHUAN WANG2,4, NESE ITUASO-CONWAY5, MING-CHE TSAI2,6, PAO-YING TSENG6, YU-LIN YEH1, CHUN-TZU CHEN7, KO‑HUANG LUE2,8, JING-GUNG CHUNG9,10 and YU-PING HSIAO1,2 1Department of Dermatology, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40201; 2Institute of Medicine, School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung 40201; Departments of 3Obstetrics and Gynecology, and 4Urology, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40201; 5Public Health, Princess Margaret Hospital, Ministry of Health, Funafuti, Tuvalu; 6International Medical Service Center, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40201; Departments of 7Chief Secretary Group and 8Pediatrics, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40201; 9Department of Biological Science and Technology, China Medical University, Taichung 40201; 10Department of Biotechnology, Asia University, Taichung 41354, Taiwan, R.O.C. Received July 1, 2014; Accepted September 18, 2014 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3806 Abstract. There is a distinct lack of knowledge on the land area of Tuvalu is only 25.9 km2, and the highest point does prevalence of skin disorders in Tuvalu. The aim of the current not exceed 4 m above sea level (1). Currently, an estimated study was to assess the prevalence of cutaneous diseases and 11,000 people live in Tuvalu (1). The Taiwan International to evaluate access dermatological care in Tuvalu. Cutaneous Cooperation and Development Fund (Taiwan ICDF) has disorders in the people of Tuvalu between 2009 and 2012 coordinated the medical resources of Taiwanese hospitals in were examined. -

Biased Signaling of G Protein Coupled Receptors (Gpcrs): Molecular Determinants of GPCR/Transducer Selectivity and Therapeutic Potential

Pharmacology & Therapeutics 200 (2019) 148–178 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacology & Therapeutics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharmthera Biased signaling of G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs): Molecular determinants of GPCR/transducer selectivity and therapeutic potential Mohammad Seyedabadi a,b, Mohammad Hossein Ghahremani c, Paul R. Albert d,⁎ a Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Iran b Education Development Center, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Iran c Department of Toxicology–Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran d Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Neuroscience, University of Ottawa, Canada article info abstract Available online 8 May 2019 G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) convey signals across membranes via interaction with G proteins. Origi- nally, an individual GPCR was thought to signal through one G protein family, comprising cognate G proteins Keywords: that mediate canonical receptor signaling. However, several deviations from canonical signaling pathways for GPCR GPCRs have been described. It is now clear that GPCRs can engage with multiple G proteins and the line between Gprotein cognate and non-cognate signaling is increasingly blurred. Furthermore, GPCRs couple to non-G protein trans- β-arrestin ducers, including β-arrestins or other scaffold proteins, to initiate additional signaling cascades. Selectivity Biased Signaling Receptor/transducer selectivity is dictated by agonist-induced receptor conformations as well as by collateral fac- Therapeutic Potential tors. In particular, ligands stabilize distinct receptor conformations to preferentially activate certain pathways, designated ‘biased signaling’. In this regard, receptor sequence alignment and mutagenesis have helped to iden- tify key receptor domains for receptor/transducer specificity. -

Cell Penetrating Peptides, Novel Vectors for Gene Therapy

pharmaceutics Review Cell Penetrating Peptides, Novel Vectors for Gene Therapy Rebecca E. Taylor 1 and Maliha Zahid 2,* 1 Mechanical Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Electrical and Computer Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 15201, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-412-692-8893; Fax: +1-412-692-6184 Received: 5 February 2020; Accepted: 1 March 2020; Published: 3 March 2020 Abstract: Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs), also known as protein transduction domains (PTDs), first identified ~25 years ago, are small, 6–30 amino acid long, synthetic, or naturally occurring peptides, able to carry variety of cargoes across the cellular membranes in an intact, functional form. Since their initial description and characterization, the field of cell penetrating peptides as vectors has exploded. The cargoes they can deliver range from other small peptides, full-length proteins, nucleic acids including RNA and DNA, liposomes, nanoparticles, and viral particles as well as radioisotopes and other fluorescent probes for imaging purposes. In this review, we will focus briefly on their history, classification system, and mechanism of transduction followed by a summary of the existing literature on use of CPPs as gene delivery vectors either in the form of modified viruses, plasmid DNA, small interfering RNA, oligonucleotides, full-length genes, DNA origami or peptide nucleic acids. Keywords: cell penetrating peptides; protein transduction domains; gene therapy; small interfering RNA 1. Introduction The plasma membrane of a cell is essential to its identity and survival, but at the same time presents a barrier to intracellular delivery of potentially diagnostic or therapeutic cargoes. -

Complementary Regulation of Caspase-1 and IL-1Β Reveals Additional Mechanisms of Dampened Inflammation in Bats

Complementary regulation of caspase-1 and IL-1β reveals additional mechanisms of dampened inflammation in bats Geraldine Goha,1, Matae Ahna,1, Feng Zhua, Lim Beng Leea, Dahai Luob,c, Aaron T. Irvinga,d,2, and Lin-Fa Wanga,e,2 aProgramme in Emerging Infectious Diseases, Duke–National University of Singapore Medical School, 169857, Singapore; bLee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, 636921, Singapore; cNTU Institute of Structural Biology, Nanyang Technological University, 636921, Singapore; dZhejiang University–University of Edinburgh Institute, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Zhejiang University International Campus, Haining, 314400, China; and eSinghealth Duke–NUS Global Health Institute, 169857, Singapore Edited by Vishva M. Dixit, Genentech, San Francisco, CA, and approved September 14, 2020 (received for review February 21, 2020) Bats have emerged as unique mammalian vectors harboring a experimental confirmation is rare. We recently demonstrated diverse range of highly lethal zoonotic viruses with minimal that NLRP3 is dampened in bats as a result of loss-of-function clinical disease. Despite having sustained complete genomic loss bat-specific isoforms and impaired transcriptional priming (9). of AIM2, regulation of the downstream inflammasome response in The stimulator of IFN genes (STING), a key adaptor to the bats is unknown. AIM2 sensing of cytoplasmic DNA triggers ASC DNA-sensing cGAS protein, is also exclusively mutated at S358 aggregation and recruits caspase-1, the central inflammasome ef- in bats, resulting in a reduced IFN response to HSV1 (10). We fector enzyme, triggering cleavage of cytokines such as IL-1β and previously reported a complete absence of Absent in melanoma inducing GSDMD-mediated pyroptotic cell death.