Max Warren, Tradition and Theology of Mission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Anglican Heritage 235

OUR ANGLICAN HERITAGE 235 OUR ANGLICAN HERITAGE.1 BY THE REV. CANON A. J. TAIT, D.D. I. The Lord is the portion of mine inheritance and of my cup : thou maintainest my lot. The lines are fallen unto me in pleasant places : yea, I have a goodly heritage.-Psalm xvi. 5, 6. EVERAL happenings of the past few months have quickened S within me the desire to increase my knowledge and under standing of the religious Movements which made the development of Church life and activity a conspicuous feature of the nineteenth century, and so to grow in appreciation of the spiritual heritage into which the Church of England has entered in this twentieth century. Some of those happenings to which I refer were par ticularly connected with the challenge of our very right to exist ence, which is being constantly reiterated by representative spokes men of the Roman Communion. My purpose therefore for these Sunday mornings in August is to speak positively about our heritage, and our indebtedness for its enrichment to the Movements of the nineteenth century, and, if time permits at the close, to give my reasons for regarding the Roman challenge as having no true foundation. In connection with the recent celebrations of the Centenary of the Oxford Movement I noted with interest a statement of the Bishop of Llandaff. After warning his hearers, as many of our leaders have recently done both in Pulpit and Press, that the battle in the near future will be with the forces of materialism and secularism, he said that the paramount need of the day was for consecrated men and women who know the meaning of mem· bership of the consecrated Society. -

Evangelikal – Radikal – Sozialkritisch. Zur Theologie Der Radika- Len Evangelikalen

EVANGELIKAL – RADIKAL – SOZIALKRITISCH. ZUR THEOLOGIE DER RADIKA- LEN EVANGELIKALEN. EINE KRITISCHE WÜRDIGUNG (THE THEOLOGY OF RA- DICAL EVANGELICALISM) by ROLAND HARDMEIER submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF J REIMER MAY 2006 *********** MTH structured Evangelikal – radikal – sozialkritisch. Zur Theologie der radikalen Evangelikalen ii DEUTSCHE ZUSAMMENFASSUNG Die vorliegende Dissertation erfasst die geschichtlichen und theologischen Grundlinien des radikalen Evangelikalismus und stellt ihn in den Kontext ähnlicher und ihn beeinflussender Theologien. Es wird aufgezeigt, dass der radikale Evangelikalismus eine evangelikale Grundkonzeption mit Elementen des Anabaptismus, des Social Gospel, der Befreiungstheologie und der Theologien im Umfeld des Öku- menischen Rates der Kirchen bereichert. Dabei wird deutlich, dass die radikale Theologie genuin e- vangelikal ist, die Einseitigkeiten der westlichen evangelikalen Theologie aber zu überwinden vermag. Besondere Aufmerksamkeit ist den Beiträgen radikaler Nord- und Lateinamerikaner gewidmet, da diese den radikalen Evangelikalismus wesentlich geprägt haben. Ziel ist es, den radikalen Evangelikalismus darzustellen, kritisch zu würdigen und für die europäische evangelikale Szene fruchtbar zu machen. Der erste Teil nennt die Quellen, aus denen sich die radikale Theologie speist. Der zweite Teil zeichnet den geschichtlichen Werdegang des radikalen Evangelika- lismus nach. Es wird nachgewiesen, dass der radikale Evangelikalismus in den dreissig Jahren seines Bestehens zu einem bestimmenden Faktor in der weltweiten evangelikalen Bewegung geworden ist. Der dritte Teil stellt die Grundzüge der radikalen Theologie mittels ausgewählter Themen dar. Er zeigt auf, dass die Radikalen die evangelikale Bewegung mit einer transformatorischen Missionstheorie konfrontiert haben, die relevant für die drängenden Probleme der Gegenwart ist. -

(SAM) BERRY Christians in Science: Looking Back – and Forward

S & CB (2015), 27, 125-152 0954–4194 MALCOLM JEEVES AND R.J. (SAM) BERRY Christians in Science: Looking Back – and Forward Christians in Science had its origins in 1944 in a small gathering of mainly postgraduate students in Cambridge. This group became the nucleus of the Research Scientists’ Christian Fellowship (which changed its name in 1988 to Christians in Science). The RSCF was originally a graduate section of the Inter-Varsity Fellowship (now the Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship), but is now an independent charity and limited company, albeit still retaining close links with UCCF. We review the seventy year history of CiS and its contributions to the maturing discussions in the faith-science area; we see a positive and developing role for the organisation. Keywords: Oliver Barclay, Donald MacKay, Reijer Hooykaas, Essays and Reviews, Victoria Institute, Research Scientists’ Christian Fellowship, God- of-the-gaps, naturalism A range of scientific discoveries in the first half of the nineteenth century raised worrying conflicts over traditional understandings of the Bible. The early geologists produced evidence that the world was much older than the few thousand years then assumed, more powerful telescopes showed that the solar system was a very small part of an extensive galaxy, and grow- ing awareness of the plants and animals of the Americas and Australasia led to unsettling suggestions that there might have been several centres of creation. These problems over biblical interpretations became focused in mid-century -

ABSTRACT Reclaiming Peace: Evangelical Scientists And

ABSTRACT Reclaiming Peace: Evangelical Scientists and Evolution After World War II Christopher M. Rios, Ph.D. Advisor: William L. Pitts, Jr., Ph.D. This dissertation argues that during the same period in which antievolutionism became a movement within American evangelicalism, two key groups of evangelical scientists attempted to initiate a countervailing trend. The American Scientific Affiliation was founded in 1941 at the encouragement of William Houghton, president of Moody Bible Institute. The Research Scientists‘ Christian Fellowship was started in London in 1944 as one of the graduate fellowship groups of Inter-Varsity Fellowship. Both organizations were established out of concern for the apparent threat stemming from contemporary science and with a desire to demonstrate the compatibility of Christian faith and science. Yet the assumptions of the respective founders and the context within which the organizations developed were notably different. At the start, the Americans assumed that reconciliation between the Bible and evolution required the latter to be proven untrue. The British never doubted the validity of evolutionary theory and were convinced from the beginning that conflict stemmed not from the teachings of science or the Bible, but from the perspectives and biases with which one approached the issues. Nevertheless, by the mid 1980s these groups became more similar than they were different. As the ASA gradually accepted evolution and developed convictions similar to those of their British counterpart, the RSCF began to experience antievolutionary resistance with greater force. To set the stage for these developments, this study begins with a short introduction to the issues and brief examination of current historiographical trends. -

Download More Information on the Buxton Family Written by R.E Davies

THE BUXTONS OF EASNEYE: AN EVANGELICAL VICTORIAN FAMILY AND THEIR SUCCESSORS BY R E DAVIES 2006 (Revised 2007) CONTENTS PREFACE CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER II: SPITALFIELDS AND LEYTONSTONE CHAPTER III: THE MOVE TO EASNEYE CHAPTER IV: THE MINISTRY OF DOING GOOD CHAPTER V: FAMILY LIFE AT EASNEYE OVER THE FIRST FORTY YEARS CHAPTER VI: THE GREAT WAR CHAPTER VII: BETWEEN THE WARS CHAPTER VIII: THE SECOND WORLD WAR CHAPTER IX: 1945 ONWARDS CHAPTER X: A NEW CHAPTER! APPENDIX 1: OWNERS AND INHABITANTS OF EASNEYE PREFACE I first came to Easneye in 1964, when I had been appointed as the Resident Tutor at All Nations Missionary College, which had just moved there from Taplow, near Maidenhead, Berkshire. I lived with my family in North Lodge, one of the cottages on the Easneye estate, for the next four years, but my connection with All Nations and Easneye has continued up to the present. I worked for thirty-four years full-time and for another seven years part-time, and now my son, who was only eighteen months old back in 1964, is a member of the All Nations faculty. I feel, therefore, that my long connection with the place gives me the interest and ability to look into and record something of the past history of Easneye and its inhabitants. Mr David Morris, the Principal of All Nations when it was at Taplow as well as for several years after the move to Easneye, and whose vision and hard work were vital in making the college what it is today, used to give a very informative and entertaining history of the site, the building, the Buxton family and the college (never dull but sometimes bordering on the over-imaginative!) When he retired, the Rev. -

Churchman 124/1 2/11/10 10:25 Page 367

124/4:Churchman 124/1 2/11/10 10:25 Page 367 367 Book Reviews TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH The Globalization of Christianity Kenneth Hylson-Smith London: PaTernosTer, 2007 237pp £12.99 ISBN: 978-1-84227-475-0 ‘European colonisaTion involved spreading disease, enslaving Their populaTions and forcing Them To converT To ChrisTianiTy…’ Thus began The Times’ review of “Dark ConTinenTs” in Channel 4’s series “ChrisTianiTy: A HisTory” (February, 2009). NoT a happy picTure of The ChrisTian missionary endeavour. And yeT The programme iTself, by wriTer, playwrighT and ChrisTian Kwame Kwei Armah was much more posiTive and showed how ChrisTianiTy had Taken rooT in conTexTualized ways across SouTh America and Africa. The weekend I read ThaT review and waTched The programme, I was also reading Hylson-SmiTh’s book. JusT as Kwame’s acTual programme was more posiTive Than The media review, so This book also gives a posiTive appraisal of The worldwide missionary movemenT and The ChrisTian Church in The face of media scepTicism and cynicism. The book is, he says, ‘a response To The many hisTorians, sociologisTs, Theologians, aTheisTs, agnosTics and media pundiTs who in recenT decades have declared ChrisTianiTy, or aT leasT The insTiTuTional Church, To be in reTreaT and even suffering from Terminal illness’. WhilsT I am noT convinced ThaT such media pundiTry or academic analysis is as widespread as iT once was, This book does show ChrisT’s Church To be healThy, vigorous and global. As such, iT encouraged me in my faiTh in The Lord Jesus who is building his Church. -

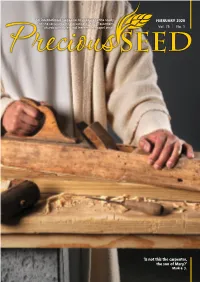

FEBRUARY 2020 of the Scriptures, the Practice of New Testament Church Principles and Interest in Gospel Work Vol

An international magazine to encourage the study FEBRUARY 2020 of the scriptures, the practice of New Testament church principles and interest in gospel work Vol. 75 | No. 1 ‘Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary?’ Mark 6. 3. BOOKS ORDER FORM Please complete this form and send with your card details to: GENERAL SERIES Precious Seed Publications, 34 Metcalfe Avenue, Killamarsh, Church Doctrine and Practice (Revised) ........................................ @ £9.50 Sheffield, S21 1HW, UK. Footprints Nurture Course (Ken Rudge), make your own multiple copies @ £15.00 Please send the following: The Minor Prophets........................................................................ @ £7.95 New Treasury of Bible Doctrine ..................................................... @ £12.00 NEW BOOKS AND SPECIAL OFFERS 100 Questions sent to Precious Seed (R. Collings) ......................... @ £7.50 Precious Seed Vol. 5....................................................................... @ £8.50 Christ and His Apostles ................................................................@ £3.00 OLD TESTAMENT OVERVIEW SERIES Living in the Promised Land ..........................................................@ £3.00 Vol. 1. Beginnings by Richard Catchpole ......................................@ £7.50 Church Doctrine and Practice (Revised) .....................................@ £9.50 Vol. 2. Laws for Life by Keith Keyser .............................................@ £7.50 The Person and Work of the Holy Spirit (Samuel Jardine) .................@ -

EVANGELICAL REVIEW of THEOLOGY Are Reprinted with Permission from the Following Journals: ‘The Bible in the WCC’, Calvin Theological Journal, Vol

EVANGELICAL REVIEW OF THEOLOGY VOLUME 2 Volume 2 • Number 2 • October 1978 p. 160a Acknowledgements The articles in this issue of the EVANGELICAL REVIEW OF THEOLOGY are reprinted with permission from the following journals: ‘The Bible in the WCC’, Calvin Theological Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2. ‘Controversy at Culture Gap’, Eternity, Vol. 27, No. 5. ‘East African Revival’, Churchman, Vol. 1, 1978. ‘Survey of Recent Literature on Islam’, International Review of Mission, LXVII, No. 265. ‘Who are the Poor’ and ‘Responses’, Theological Forum of the Reformed Ecumenical Synod, No. 1, Feb. 1978. ‘The Great Commission of Matthew 28: 18–20’, Reformed Theological Review, Vol. 35, No. 3. ‘A Glimpse of Christian Community Life in China’, Tenth, Jan. 1977. ‘TEE: Service or Subversion?’, Extension Seminary Quarterly Bulletin, No. 4. ‘TEE in Zaire: Mission or Movement?’, Ministerial Formation, No. 2. ‘Theology for the People’ and ‘Para-Education: Isolation or Integration?’ are printed with the permission of the authors. p. 161 Editorial For an increasing number of Christians the message of the Bible is no longer self-evident. The cultural gap between the ancient world and our secular technological world continues to grow. From the standpoint of a Christian caught in poverty, social injustice and political oppression, commentaries on the Bible written by scholars living in an academic atmosphere of middle and upper class society often seem flat and barely relevant. They fail to deal with what Hans-Georg Gadamer calls the central problem of hermeneutics, the problem of application. While we have good reasons to seriously question the new hermeneutic of Bultmann and his successors in their use of the dialectical method and the existentialism that rejects the concept of propositional revelation, the new hermeneutic does seek to uncover the hidden and unexamined presuppositions with which all of us come to the Scriptures. -

Knowing Doing

KNOWING OING &D. C S L EWI S I N S TITUTE PROFILE IN FAITH Bright Messenger of God: Bishop Handley Moule by David B. Calhoun Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri This article originally appeared in the Spring 2011 issue of Knowing & Doing. n May 17, 1921, while traveling on a train, Bish- his mother read to him from op Handley Moule wrote a short poem about great books, instilling in him a Othree places in England that he loved: “Three lifelong quest for learning. At Affections in One Life.” the age of sixteen, he had mem- The first was the place of his birth—Dorset— orized the Greek text of Ephe- his “mother.” sians and Philippians. From his brothers he learned the arts Dorset, my heart’s first warmth is thine of bell ringing and woodcarv- Till all my years are done, ing. The Moule sons compiled David B. Calhoun O fair and dear, O mother mine. a remarkable record of service in education and the O glory of thy son. church, two of them becoming missionaries, both as bishops in China. Handley Carr Glyn Moule was born on Decem- The revival of 1859 touched Fordington. Nightly ber 23, 1841, the youngest of eight sons of Henry and meetings in Henry Moule’s church featured no great Mary Evans Moule. Handley’s father was the evan- preacher but simply the reading of Scripture and gelical Anglican vicar of Fordington, now a suburb prayer. Even so, many were “awakened, awed and of Dorchester. -

The A~~=~~~Or~:~Rn ~::~~ Knd. = Work Can Scarcely Be Found

OCI'OBER, 1933. ~llllllliiiiiiiiii!IIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIII!IIIIIIIIIIliiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUI~ = = With outstretched Hands = The A~~=~~~or~:~rn ~::~~ knd. = Work can scarcely be found. - :::~and children are the greatest suflerers. extra help for Aged Widows' Home, = Special help for sick children, especially T .B. cases, a - PL::::d~::r;~:d :~~. Armenian Massacre Relief at the office of Bible Lands Missions' Aid Society 7 6P 5 T RAN D, L 0 N D 0 N, W. C. 2. HARRY FEAR, Esq., J.P., Treasurer. =:a Rev. S. W. GENTLE·CACKETT, Secretary. ~ = lfniiiiUIIIIIIllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllliiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIOIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIOIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIi ! THE CHUROHMAN ADVERTISER. Publications obtainable from the CHURCH BOOK ROOM 7 WINE OFFICE COURT, E.C.4. ABOUT THE FEET OF GOD. By Canon E. R. PRicE DEVEREux, M.A., LL.B. Paper cover, 3d. AT THE LORD'S TABLE. A Manual for Communicants, with the Communion Service. By the BISHOP OF CBE LMSFORD. Cloth gilt, Is. 6d. ; cloth, Is. A COMMUNICANT'S MANUAL. By the BISHOP OF MIDDLETON. Id., or 7s. per IOO. COMMUNICANTS' UNION SERVICE. Arranged by Canon A. E. BARNRS-LAWRENCE. Id., or SS. per IOO. THE DAILY WALK. Devotions for every day of the year. Compiled by CORNELIA, LADY WIMBORNE. ss. and 7s. 6d. DEVOTIONAL STUDIES IN THE HOLY COMMUNION SER VICE. Six Sermons by Rev. A. ST. JoHN THORPE, M.A. 6d.; cloth, gd. FAMILY PRAYERS. By Rev. A. F. THoRNHILL, M.A. Limp cloth, 6d. ; paper cover, zd. FATHER AND SON. A Boy's Prayers for a Week. By Rev. R. R. WILLIAMS, B.A. Cloth, gd. ; duxeen, 3d. A GIRL'S WEEK OF PRAYER. By E. M. -

The Late Rev. Robert Clark. the Missions

THE LATE REV. ROBERT CLARK. THE MISSIONS OF THE CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY A~D THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND ZENANA MISSIONARY · SOCIETY IN THE PUNJAB AND SINDH BY THE LATE REv. ROBERT CLARK, M.A. EDITED .AND REPISED BY ROBERT MACONACHIE, LATE I.C.S. LONDON: CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY SALi SBU R Y SQUARE, E.C. 1904 PREFATORY NOTE. --+---- THE first edition of this book was published in 18~5. In 1899 Mr. Robert Clark sent the copy for a second and revised edition, omitting some parts of the original work, adding new matter, and bringing the history of the different branches of the Mission up to date. At the same time he generously remitted a sum of money to cover in part the expense of the new edition. It was his wish that Mr. R. Maconachie, for many years a Civil officer in the Punjab, and a member of the C.M.S. Lahore Corre sponding Committee, would edit the book; and this task Mr. Maconachie, who had returned to England and was now a member of the Committee at home, kindly undertook. Before, however, he could go through the revised copy, Mr. Clark died, and this threw the whole responsibility of the work upon the editor. Mr. Maconachie then, after a careful examination of the revision, con sidered that the amount of matter provided was more than could be produced for a price at which the book could be sold. He therefore set to work to condense the whole, and this involved the virtual re-writing of some of the chapters. -

Cathedral and University and Other Sermons

‘Il Schoo 1 of Wi Theology at | Clarem ir The Library SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AT CLAREMONT WEST FOOTHILL AT COLLEGE AVENUE CLAREMONT, CALIFORNIA CATHEDRAL AND UNIVERSITY AND OTHER SERMONS ALD 6. A in Gy , 1 CATHEDRAL AND UNIVERSITY AND OTHER SERMONS BY HANDLEY C. G. MOULE, D.D. BISHOP OF DURHAM HODDER AND STOUGHTON LIMITED LONDON ‘Theology Library SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AT CLAREMONT Calitornia PriInTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY Ricwarp Cray & Sons, Limitep, BRUNSWICK ST., STAMFORD STs, SeEs I) AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK. SEVERAL collections of Dr. Handley Moule’s sermons have been made in former years, the last published as lately as 1908. But it has been thought that many readers, who have valued his teaching from study or pulpit, would welcome yet one more small volume of his latest and perhaps strongest period—strongest in fervency and in courage of thought and utterance. In a deep sense, no doubt, this preacher had one theme only—his Master and Lord ;—but his interest and sympathies ranged widely and touched all things human ; and in the choice of these sermons varzety of subject and occasion ~has been aimed at, to illustrate not his = spirituality only but his humanity ; for example E(to mention only three characteristic attitudes), ~his almost worship of womanhood and mother- hood and the home, his reverence towards the THEOLOGY LIBRARY SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AT CLAREMONT A 5693 CALIFORNIA great medical profession, and his grateful and enthusiastic affection for persons and for places whose debtor he felt himself to be. This last emotion finds a voice in three of the sermons ; notably in ‘‘Durham Cathedral” (No.