Management of Movement Disorders and Extrapyramidal Side Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Appendix A: Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (Pips) for Older People (Modified from ‘STOPP/START 2’ O’Mahony Et Al 2014)

Appendix A: Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (PIPs) for older people (modified from ‘STOPP/START 2’ O’Mahony et al 2014) Consider holding (or deprescribing - consult with patient): 1. Any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication 2. Any drug prescribed beyond the recommended duration, where well-defined 3. Any duplicate drug class (optimise monotherapy) Avoid hazardous combinations e.g.: 1. The Triple Whammy: NSAID + ACE/ARB + diuretic in all ≥ 65 year olds (NHS Scotland 2015) 2. Sick Day Rules drugs: Metformin or ACEi/ARB or a diuretic or NSAID in ≥ 65 year olds presenting with dehydration and/or acute kidney injury (AKI) (NHS Scotland 2015) 3. Anticholinergic Burden (ACB): Any additional medicine with anticholinergic properties when already on an Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic (listed overleaf) in > 65 year olds (risk of falls, increased anticholinergic toxicity: confusion, agitation, acute glaucoma, urinary retention, constipation). The following are known to contribute to the ACB: Amantadine Antidepressants, tricyclic: Amitriptyline, Clomipramine, Dosulepin, Doxepin, Imipramine, Nortriptyline, Trimipramine and SSRIs: Fluoxetine, Paroxetine Antihistamines, first generation (sedating): Clemastine, Chlorphenamine, Cyproheptadine, Diphenhydramine/-hydrinate, Hydroxyzine, Promethazine; also Cetirizine, Loratidine Antipsychotics: especially Clozapine, Fluphenazine, Haloperidol, Olanzepine, and phenothiazines e.g. Prochlorperazine, Trifluoperazine Baclofen Carbamazepine Disopyramide Loperamide Oxcarbazepine Pethidine -

Eslicarbazepine Acetate: a New Improvement on a Classic Drug Family for the Treatment of Partial-Onset Seizures

Drugs R D DOI 10.1007/s40268-017-0197-5 REVIEW ARTICLE Eslicarbazepine Acetate: A New Improvement on a Classic Drug Family for the Treatment of Partial-Onset Seizures 1 1 1 Graciana L. Galiana • Angela C. Gauthier • Richard H. Mattson Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Eslicarbazepine acetate is a new anti-epileptic drug belonging to the dibenzazepine carboxamide family Key Points that is currently approved as adjunctive therapy and monotherapy for partial-onset (focal) seizures. The drug Eslicarbazepine acetate is an effective and safe enhances slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium chan- treatment option for partial-onset seizures as nels and subsequently reduces the activity of rapidly firing adjunctive therapy and monotherapy. neurons. Eslicarbazepine acetate has few, but some, drug– drug interactions. It is a weak enzyme inducer and it Eslicarbazepine acetate improves upon its inhibits cytochrome P450 2C19, but it affects a smaller predecessors, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, by assortment of enzymes than carbamazepine. Clinical being available in a once-daily regimen, interacting studies using eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treat- with a smaller range of drugs, and causing less side ment or monotherapy have demonstrated its efficacy in effects. patients with refractory or newly diagnosed focal seizures. The drug is generally well tolerated, and the most common side effects include dizziness, headache, and diplopia. One of the greatest strengths of eslicarbazepine acetate is its ability to be administered only once per day. Eslicar- 1 Introduction bazepine acetate has many advantages over older anti- epileptic drugs, and it should be strongly considered when Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder affecting over treating patients with partial-onset epilepsy. -

Chapter 25 Mechanisms of Action of Antiepileptic Drugs

Chapter 25 Mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs GRAEME J. SILLS Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Liverpool _________________________________________________________________________ Introduction The serendipitous discovery of the anticonvulsant properties of phenobarbital in 1912 marked the foundation of the modern pharmacotherapy of epilepsy. The subsequent 70 years saw the introduction of phenytoin, ethosuximide, carbamazepine, sodium valproate and a range of benzodiazepines. Collectively, these compounds have come to be regarded as the ‘established’ antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). A concerted period of development of drugs for epilepsy throughout the 1980s and 1990s has resulted (to date) in 16 new agents being licensed as add-on treatment for difficult-to-control adult and/or paediatric epilepsy, with some becoming available as monotherapy for newly diagnosed patients. Together, these have become known as the ‘modern’ AEDs. Throughout this period of unprecedented drug development, there have also been considerable advances in our understanding of how antiepileptic agents exert their effects at the cellular level. AEDs are neither preventive nor curative and are employed solely as a means of controlling symptoms (i.e. suppression of seizures). Recurrent seizure activity is the manifestation of an intermittent and excessive hyperexcitability of the nervous system and, while the pharmacological minutiae of currently marketed AEDs remain to be completely unravelled, these agents essentially redress the balance between neuronal excitation and inhibition. Three major classes of mechanism are recognised: modulation of voltage-gated ion channels; enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission; and attenuation of glutamate-mediated excitatory neurotransmission. The principal pharmacological targets of currently available AEDs are highlighted in Table 1 and discussed further below. -

Hypersalivation in Children and Adults

Pharmacological Management of Hypersalivation in Children and Adults Scope: Adult patients with Parkinson’s disease, children with neurodisability, cerebral palsy, long-term ventilation with drooling, and drug-induced hypersalivation. ASSESSMENT OF SEVERITY/RESPONSE TO TREATMENT: Severity of drooling can be assessed subjectively via discussion with patients and their carers/parents and by observation. Amount of drooling can be quantified by measuring the number of bibs required per day and this can also be graded using the Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg scale: • 1 = Dry (no drooling) • 2 = Mild (moist lips) • 3 = Moderate (wet lips and chin) • 4 = Severe (damp clothing) CONSIDERATIONS FOR PRESCRIBING/TITRATION No evidence to support the use of one particular treatment over another. Drug choice is to be determined by individual patient factors. When prescribing/titrating antimuscarinic drugs to treat hypersalivation always take account of: • Coexisting conditions (for example, history of urinary retention, constipation, glaucoma, dental issues, reflux etc.) • Use of other existing medication affecting the total antimuscarinic burden • Risk of adverse effects Titrate dose upward until the desired level of dryness, side effects or maximum dose reached. Take into account the preferences of the patients and their carers/ parents, and the age range and indication covered by the marketing authorisations (see individual summaries of product characteristics, BNF or BNFc for full prescribing information). FIRST LINE DRUG TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR ADULTS -

Clinical Review, Adverse Events

Clinical Review, Adverse Events Drug: Carbamazepine NDA: 16-608, Tegretol 20-712, Carbatrol 21-710, Equetro Adverse Event: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Reviewer: Ronald Farkas, MD, PhD Medical Reviewer, DNP, ODE I 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Background Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an anticonvulsant with FDA-approved indications in epilepsy, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. CBZ is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), closely related serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions that can be permanently disabling or fatal. Other anticonvulsants, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, and lamotrigine are also associated with SJS/TEN, as are members of a variety of other drug classes, including nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs and sulfa drugs. The incidence of CBZ-associated SJS/TEN has been considered “extremely rare,” as noted in current U.S. drug labeling. However, recent publications and postmarketing data suggest that CBZ- associated SJS/TEN occurs at a much higher rate in some Asian populations, about 2.5 cases per 1,000 new exposures, and that most of this increased risk is in individuals carrying a specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele, HLA-B*1502. This HLA-B allele is present in about 5- to 20% of many, but not all, Asian populations, and is also present in about 2- to 4% of South Asians/Indians. The allele is also present at a lower frequency, < 1%, in several other ethnic groups around the world (although likely due to distant Asian ancestry). About 10% of U.S. Asians carry HLA-B*1502. HLA-B*1502 is generally not present in the U.S. -

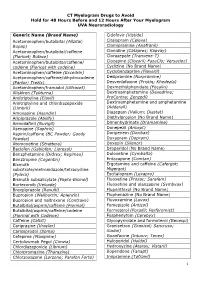

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

A Brief Overview of Psychotropic Medication Use for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATION USE FOR PERSONS WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES INTRODUCTION Individuals with intellectual disabilities are not uncommonly prescribed psychotropic medications. Too often, historically, such agents have been used to try to improve behavioral control without adequate understanding of the antecedents, purpose, and reinforcement of the problematic behavior. While an individual with an intellectual disability may experience a depressive, anxiety, or psychotic disorder in the more typical sense some individuals experience a pattern of anxiety/alarm/arousal leading to affective dysregulation and impulsive behavior. The anxiety can be stimulated by environmental change, physical discomfort, cues related to past trauma, overstimulation, boredom, confusion, or other unpleasant states. Addressing what is causing the distress or reinforcing the behavioral response is the most important thing (though not always easy). Psychotropic medications may be useful for treating more typically presenting psychiatric illnesses as well as being part of more comprehensive plans to attenuate risk behaviors. An individual with intellectual disabilities who seems sad, is withdrawn, shows low energy and lack of interest, is eating or sleeping more or less, or may be more irritable could be suffering from a depression that needs medication treatment. On the other hand an individual with intellectual disabilities who demonstrates aggression, property destruction, self-injury, or other forms of “dyscontrol” may be helped by medication aimed at blunting the anxiety/alarm and/or blocking its escalation into aggression or other dangerous behaviors. In such instances the medications are just part of an overall strategy or plan to help the individual avoid the “need” to engage in such behavior. -

The Use and Potential Abuse of Anticholinergic

British Journal of Clinical DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03342.x Pharmacology Correspondence Dr Pål Gjerden, Department of Psychiatry, The use and potential abuse Telemark Hospital, N-3710 Skien, Norway. Tel: + 47 3500 3476 Fax: + 47 3500 3187 of anticholinergic E-mail: [email protected] ---------------------------------------------------------------------- antiparkinson drugs in Keywords adverse effects, anticholinergic agents, antiparkinson agents, antipsychotic Norway: a agents, drug abuse ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Received pharmacoepidemiological 9 June 2008 Accepted 18 October 2008 study Published Early View 16 December 2008 Pål Gjerden, Jørgen G. Bramness1 & Lars Slørdal2 Department of Psychiatry,Telemark Hospital, Skien, 1Department of Pharmacoepidemiology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo and 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Children’s and Women’s Health, Norwegian University of Science and Technology,Trondheim, Norway WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT • Anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs are used to ameliorate extrapyramidal AIMS symptoms caused by either Parkinson’s The use of anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs is assumed to have disease or antipsychotic drugs, but their use shifted from the therapy of Parkinson’s disease to the amelioration in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease is of extrapyramidal adverse effects induced by antipsychotic drugs. There is a considerable body of data suggesting that anticholinergic assumed to be in decline. antiparkinson drugs have a potential for abuse.The aim was to • Patients with psychotic conditions have a investigate the use and potential abuse of this class of drugs in Norway. high prevalence of abuse of drugs, including anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs. METHODS Data were drawn from the Norwegian Prescription Database on sales to a total of 73 964 patients in 2004 of biperiden and orphenadrine, and use in patients with Parkinson’s disease or in patients who were WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS also prescribed antipsychotic agents. -

![APTIOM (Eslicarbazepine Acetate) Is (S)-10-Acetoxy-10,11-Dihydro-5H Dibenz[B,F]Azepine-5-Carboxamide](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5440/aptiom-eslicarbazepine-acetate-is-s-10-acetoxy-10-11-dihydro-5h%C2%AD-dibenz-b-f-azepine-5-carboxamide-1265440.webp)

APTIOM (Eslicarbazepine Acetate) Is (S)-10-Acetoxy-10,11-Dihydro-5H Dibenz[B,F]Azepine-5-Carboxamide

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION Monitor and discontinue if another cause cannot be established. (5.2, 5.3, These highlights do not include all the information needed to use 5.4) APTIOM safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for • Hyponatremia: Monitor sodium levels in patients at risk or patients APTIOM. experiencing hyponatremia symptoms. (5.5) • Neurological Adverse Reactions: Monitor for dizziness, disturbance in gait APTIOM® (eslicarbazepine acetate) tablets, for oral use and coordination, somnolence, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and visual Initial U.S. Approval: 2013 changes. Use caution when driving or operating machinery. (5.6) • Withdrawal of APTIOM: Withdraw APTIOM gradually to minimize the ---------------------------RECENT MAJOR CHANGES------------------------- risk of increased seizure frequency and status epilepticus. (2.6, 5.7, 8.1) Indications and Usage (1) 9/2017 • Dosage and Administration (2) 9/2017 Drug Induced Liver Injury: Discontinue APTIOM in patients with jaundice Warnings and Precautions (5) 9/2017 or evidence of significant liver injury. (5.8) • Hematologic Adverse Reactions: Consider discontinuing. (5.10) ----------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE-------------------------- APTIOM is indicated for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in patients 4 ------------------------------ADVERSE REACTIONS------------------------------ years of age and older. (1) • Most common adverse reactions in adult patients receiving APTIOM (≥4% and ≥2% greater than placebo): dizziness, somnolence, nausea, headache, ----------------------DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION---------------------- diplopia, vomiting, fatigue, vertigo, ataxia, blurred vision, and tremor. (6.1) • Adult Patients: The recommended initial dosage of APTIOM is 400 mg • Adverse reactions in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adult once daily. For some patients, treatment may be initiated at 800 mg once patients. daily if the need for seizure reduction outweighs an increased risk of adverse reactions. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Journal of Central Nervous System Disease a Review Of

Journal of Central Nervous System Disease OPEN ACCESS Full open access to this and thousands of other papers at EXPERT REVIEW http://www.la-press.com. A Review of Eslicarbazepine Acetate for the Adjunctive Treatment of Partial-Onset Epilepsy Rajinder P. Singh and Jorge J. Asconapé Department of Neurology, Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Illinois 60153, USA. Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: Eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) is a novel antiepileptic drug indicated for the treatment of partial-onset seizures. Structurally, it belongs to the dibenzazepine family and is closely related to carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. Its main mechanism of action is by blocking the voltage-gated sodium channel. ESL is a pro-drug that is rapidly metabolized almost exclusively into S-licarbazepine, the biologically active drug. It has a favorable pharmacokinetic and drug-drug interaction profile. However, it may induce the metabolism of oral contraceptives and should be used with caution in females of child-bearing age. In the pre-marketing placebo-controlled clinical trials ESL has proven effective as adjunctive therapy in adult patients with refractory of partial-onset seizures. Best results were observed on a single daily dose between 800 and 1200 mg. In general, ESL was well tolerated, with most common dose-related side effects including dizziness, somnolence, headache, nausea and vomiting. Hyponatremia has been observed (0.6%–1.3%), but the incidence appears to be lower than with the use of oxcarbazepine. There is very limited information on the use of ESL in children or as monotherapy. Keywords: eslicarbazepine, licarbazepine, dibenzazepine, voltage-gated sodium channel, partial-onset seizures, epilepsy Journal of Central Nervous System Disease 2011:3 179–187 doi: 10.4137/JCNSD.S4888 This article is available from http://www.la-press.com.