West Essex CCG Anticholinergic Side-Effects and Prescribing Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

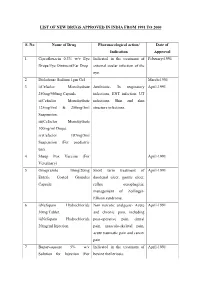

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Dosulepin Prescribing

SAFETY BULLETIN: DOSULEPIN PRESCRIBING In December 2007, the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued safety advice around prescribing of dosulepin, related to the narrow margin between therapeutic doses and potentially fatal doses. Nevertheless, dosulepin continues to be prescribed widely. Over eight years after the safety advice was published, prescribing of dosulepin in the Dorset area remains high. In the South West area, Dorset CCG was the highest prescriber of dosulepin for the 2015/16 financial year (3.238% of all antidepressant items). Of the 209 CCGs in the UK, Dorset is the fourteenth highest prescriber of dosulepin, and well above the national average of 2.111%. The following points summarise the reasons that dosulepin is not recommended for prescribing nationally, and in Dorset: Dosulepin has a small margin of safety between the (maximum) therapeutic dose and potentially fatal doses. The NICE guideline on depression in adults recommends that dosulepin should not be prescribed for adults with depression because evidence supporting its tolerability relative to other antidepressants is outweighed by the increased cardiac risk and toxicity in overdose. Dosulepin has also been used ‘off label’ in other indications such as fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. However the evidence for use in in this way is weak, and is not recommended. The lethal dose of dosulepin is relatively low and can be potentiated by alcohol and other CNS depressants. Dosulepin overdose is associated with high mortality and can occur rapidly, even before hospital treatment can be received. Onset of toxicity occurs within 4-6 hours. Every year, up to 200 people in England and Wales fatally overdose with dosulepin. -

Dose Equivalents of Antidepressants Evidence-Based Recommendations

Journal of Affective Disorders 180 (2015) 179–184 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Affective Disorders journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jad Research report Dose equivalents of antidepressants: Evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials Yu Hayasaka a,n, Marianna Purgato b, Laura R Magni c, Yusuke Ogawa a, Nozomi Takeshima a, Andrea Cipriani b,d, Corrado Barbui b, Stefan Leucht e, Toshi A Furukawa a a Department of Health Promotion and Human Behavior, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine/School of Public Health, Yoshida Konoe-cho, Sakyo- ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan b Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Section of Psychiatry, University of Verona, Policlinico “G.B.Rossi”, Pzz.le L.A. Scuro, 10, Verona 37134, Italy c Psychiatric Unit, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Centro San Giovanni di Dio, Fatebenefratelli, Brescia, Italy d Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK e Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Technische Universität München, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Ismaningerstr. 22, 81675 Munich, Germany article info abstract Article history: Background: Dose equivalence of antidepressants is critically important for clinical practice and for Received 4 February 2015 research. There are several methods to define and calculate dose equivalence but for antidepressants, Received in revised form only daily defined dose and consensus methods have been applied to date. The purpose of the present 10 March 2015 study is to examine dose equivalence of antidepressants by a less arbitrary and more systematic method. Accepted 12 March 2015 Methods: We used data from all randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose trials comparing fluoxetine or Available online 31 March 2015 paroxetine as standard drugs with any other active antidepressants as monotherapy in the acute phase Keywords: treatment of unipolar depression. -

Appendix A: Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (Pips) for Older People (Modified from ‘STOPP/START 2’ O’Mahony Et Al 2014)

Appendix A: Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (PIPs) for older people (modified from ‘STOPP/START 2’ O’Mahony et al 2014) Consider holding (or deprescribing - consult with patient): 1. Any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication 2. Any drug prescribed beyond the recommended duration, where well-defined 3. Any duplicate drug class (optimise monotherapy) Avoid hazardous combinations e.g.: 1. The Triple Whammy: NSAID + ACE/ARB + diuretic in all ≥ 65 year olds (NHS Scotland 2015) 2. Sick Day Rules drugs: Metformin or ACEi/ARB or a diuretic or NSAID in ≥ 65 year olds presenting with dehydration and/or acute kidney injury (AKI) (NHS Scotland 2015) 3. Anticholinergic Burden (ACB): Any additional medicine with anticholinergic properties when already on an Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic (listed overleaf) in > 65 year olds (risk of falls, increased anticholinergic toxicity: confusion, agitation, acute glaucoma, urinary retention, constipation). The following are known to contribute to the ACB: Amantadine Antidepressants, tricyclic: Amitriptyline, Clomipramine, Dosulepin, Doxepin, Imipramine, Nortriptyline, Trimipramine and SSRIs: Fluoxetine, Paroxetine Antihistamines, first generation (sedating): Clemastine, Chlorphenamine, Cyproheptadine, Diphenhydramine/-hydrinate, Hydroxyzine, Promethazine; also Cetirizine, Loratidine Antipsychotics: especially Clozapine, Fluphenazine, Haloperidol, Olanzepine, and phenothiazines e.g. Prochlorperazine, Trifluoperazine Baclofen Carbamazepine Disopyramide Loperamide Oxcarbazepine Pethidine -

Guidelines for the Forensic Analysis of Drugs Facilitating Sexual Assault and Other Criminal Acts

Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Guidelines for the Forensic analysis of drugs facilitating sexual assault and other criminal acts United Nations publication Printed in Austria ST/NAR/45 *1186331*V.11-86331—December 2011 —300 Photo credits: UNODC Photo Library, iStock.com/Abel Mitja Varela Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Guidelines for the forensic analysis of drugs facilitating sexual assault and other criminal acts UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 ST/NAR/45 © United Nations, December 2011. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. List of abbreviations . v Acknowledgements .......................................... vii 1. Introduction............................................. 1 1.1. Background ........................................ 1 1.2. Purpose and scope of the manual ...................... 2 2. Investigative and analytical challenges ....................... 5 3 Evidence collection ...................................... 9 3.1. Evidence collection kits .............................. 9 3.2. Sample transfer and storage........................... 10 3.3. Biological samples and sampling ...................... 11 3.4. Other samples ...................................... 12 4. Analytical considerations .................................. 13 4.1. Substances encountered in DFSA and other DFC cases .... 13 4.2. Procedures and analytical strategy...................... 14 4.3. Analytical methodology .............................. 15 4.4. -

Chlorphenamine Maleate)

Package leaflet: Information for the patient Chlorphenamine 10 mg/ml Solution for Injection (Chlorphenamine Maleate) Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. − Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. − If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or nurse. − If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or nurse. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet: 1. What Chlorphenamine is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before Chlorphenamine is given 3. How Chlorphenamine is given 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Chlorphenamine 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Chlorphenamine is and what it is used for Chlorphenamine 10 mg/ml Solution for Injection contains the active ingredient chlorphenamine maleate which is an antihistamine. Chlorphenamine is indicated in adults and children (aged 1 month to 18 years) for the treatment of acute allergic reactions. These medicines inhibit the release of histamine into the body that occurs during an allergic reaction. This product relieves some of the main symptoms of a severe allergic reaction. 2. What you need to know before Chlorphenamine is given You MUST NOT be given Chlorphenamine: if you are allergic to chlorphenamine maleate or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6) if you have had monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) antidepressive treatment within the past 14 days. Warnings and precautions Talk to your doctor or nurse before you are given this medicine if you: are being treated for an overactive thyroid or enlarged prostate gland have epilepsy, raised blood pressure within the eye or glaucoma, very high blood pressure, heart, liver, asthma or other chest diseases. -

Research Article RP-HPLC Method for Determination of Several Nsaids and Their Combination Drugs

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Chromatography Research International Volume 2013, Article ID 242868, 13 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/242868 Research Article RP-HPLC Method for Determination of Several NSAIDs and Their Combination Drugs Prinesh N. Patel, Gananadhamu Samanthula, Vishalkumar Shrigod, Sudipkumar C. Modh, and Jainishkumar R. Chaudhari Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER), Balanagar, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh 500037, India Correspondence should be addressed to Gananadhamu Samanthula; [email protected] Received 29 June 2013; Accepted 13 October 2013 Academic Editor: Andrew Shalliker Copyright © 2013 Prinesh N. Patel et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. An RP-HPLC method for simultaneous determination of 9 NSAIDs (paracetamol, salicylic acid, ibuprofen, naproxen, aceclofenac, diclofenac, ketorolac, etoricoxib, and aspirin) and their commonly prescribed combination drugs (thiocolchicoside, moxifloxacin, clopidogrel, chlorpheniramine maleate, dextromethorphan, and domperidone) was established. The separation was performed on ∘ Kromasil C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 m) at 35 C using 15 mM phosphate buffer pH 3.25 and acetonitrile with gradient elution ata flow rate of 1.1 mL/min. The detection was performed by a diode array detector (DAD) at 230 nm with total run time of 30min. 2 Calibration curves were linear with correlation coefficients of determinationr ( ) > 0.999. Limit of detection (LOD) and Limit of quantification (LOQ) ranged from 0.04 to 0.97 g/mL and from 0.64 to 3.24 g/mL, respectively. -

MSM Cross Reference Antihistamine Decongestant 20100701 Final Posted

MISSISSIPPI DIVISION OF MEDICAID Antihistamine/Decongestant Product and Active Ingredient Cross-Reference List The agents listed below are the antihistamine/decongestant drug products listed in the Mississippi Medicaid Preferred Drug List (PDL). This is a cross-reference between the drug product name and its active ingredients to reference the antihistamine/decongestant portion of the PDL. For more information concerning the PDL, including non- preferred agents, the OTC formulary, and other specifics, please visit our website at www.medicaid.ms.gov. List Effective 07/16/10 Therapeutic Class Active Ingredients Preferred Non-Preferred ANTIHISTAMINES - 1ST GENERATION BROMPHENIRAMINE MALEATE BPM BROMAX BROMPHENIRAMINE MALEATE J-TAN PD BROMSPIRO LODRANE 24 LOHIST 12HR VAZOL BROMPHENIRAMINE TANNATE BROMPHENIRAMINE TANNATE J-TAN P-TEX BROMPHENIRAMINE/DIPHENHYDRAM ALA-HIST CARBINOXAMINE MALEATE CARBINOXAMINE MALEATE PALGIC CHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE CHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE CPM 12 CHLORPHENIRAMINE TANNATE ED CHLORPED ED-CHLOR-TAN MYCI CHLOR-TAN MYCI CHLORPED PEDIAPHYL TANAHIST-PD CLEMASTINE FUMARATE CLEMASTINE FUMARATE CYPROHEPTADINE HCL CYPROHEPTADINE HCL DEXCHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE DEXCHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE DIPHENHYDRAMINE HCL ALLERGY MEDICINE ALLERGY RELIEF BANOPHEN BENADRYL BENADRYL ALLERGY CHILDREN'S ALLERGY CHILDREN'S COLD & ALLERGY COMPLETE ALLERGY DIPHEDRYL DIPHENDRYL DIPHENHIST DIPHENHYDRAMINE HCL DYTUSS GENAHIST HYDRAMINE MEDI-PHEDRYL PHARBEDRYL Q-DRYL QUENALIN SILADRYL SILPHEN DIPHENHYDRAMINE TANNATE DIPHENMAX DOXYLAMINE SUCCINATE -

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

Anticholinergic Drugs Improve Symptoms but Increase Dry Mouth in Adults with Overactive Bladder Syndrome

Source of funding: Evid Based Nurs: first published as 10.1136/ebn.6.2.49 on 1 April 2003. Downloaded from Review: anticholinergic drugs improve symptoms but Health Research Council of Aotearoa increase dry mouth in adults with overactive bladder New Zealand. syndrome For correspondence: Jean Hay-Smith, Hay-Smith J, Herbison P,Ellis G, et al. Anticholinergic drugs versus placebo for overactive bladder syndrome in adults. Dunedin School of Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003781 (latest version May 29 2002). Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, New QUESTION: What are the effects of anticholinergic drugs in adults with overactive Zealand. jean.hay-smith@ bladder syndrome? otago.ac.nz Data sources Parallel arm studies of anticholinergic drugs v placebo for overactive bladder syndrome in Studies were identified by searching the Cochrane adults at 12 days to 12 weeks* Incontinence Group trials register (to January 2002) Weighted event rates and reference lists of relevant papers. Anticholinergic Study selection Outcomes drugs Placebo RBI (95% CI) NNT (CI) Randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials in Self reported cure or adults with symptomatic diagnosis of overactive bladder improvement (8 studies) 63% 45% 41% (29 to 54) 6 (5 to 8) syndrome, urodynamic diagnosis of detrusor overactiv- RRI (CI) NNH (CI) ity, or both, that compared an anticholinergic drug Dry mouth (20 studies) 36% 15% 138 (70 to 232) 5 (4 to 7) (given to decrease symptoms of overactive bladder) with Outcomes Weighted mean difference (CI) placebo or no treatment. Studies of darifenacin, emepronium bromide or carrageenate, dicyclomine Number of leakage episodes in 24 hours (9 − chloride, oxybutynin chloride, propiverine, propanthe- studies) 0.56 (–0.73 to –0.39) Number of micturitions in 24 hours (8 studies) −0.59 (–0.83 to –0.36) line bromide, tolterodine, and trospium chloride were Maximum cystometric volume (ml) (12 studies) 54.3 (43.0 to 65.7) included. -

2-Bromopyridine Safety Data Sheet Jubilant Ingrevia Limited

2-Bromopyridine Safety Data Sheet According to the federal final rule of hazard communication revised on 2012 (HazCom 2012) Date of Compilation : July 03 ’ 2019 Date of Revision : February 09 ’ 2021 Revision due date : January 2024 Revision Number : 01 Version Name : 0034Gj Ghs01 Div.3 sds 2-Bromopyridine Supersedes date : July 03 ’ 2019 Supersedes version : 0034Gj Ghs00 Div.3 sds 2-Bromopyridine Jubilant Ingrevia Limited Page 1 of 9 2-Bromopyridine Safety Data Sheet According to the federal final rule of hazard communication revised on 2012 (HazCom 2012) SECTION 1: IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE/MIXTURE AND OF THE COMPANY/UNDERTAKING 1.1. Product identifier PRODUCT NAME : 2-Bromopyridine CAS RN : 109-04-6 EC# : 203-641-6 SYNONYMS : 2-Pyridyl bromide, Pyridine, 2-bromo-, beta-Bromopyridine, o-Bromopyridine SYSTEMATIC NAME : 2-Bromopyridine, -Pyridine, 2-bromo- MOLECULAR FORMULA : C5H4BrN STRUCTURAL FORMULA N Br 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against 1.2.1. Relevant identified uses 2-Bromopyridine is used as an intermediate in the pharmaceutical industry for the manufacture of Atazanavir (an antiretroviral drug), Carbinoxamine, Chloropyramine, triprolidine (antihistamine drugs), Disopyramide Phosphate (an antiarrythmic drug), Mefloquine (antimalarial drug), Pipradrol (mild CNS stimulant) etc. Uses advised against: None 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Jubilant Ingrevia Limited REGISTERED & FACTORY OFFICE: Jubilant Ingrevia Limited Bhartiagram, Gajraula , District: Amroha, Uttar Pradesh-244223, India PHONE NO: +91-5924-252353 to 252360 Contact Department-Safety: Ext. 7424 , FAX NO : +91-5924-252352 HEAD OFFICE: Jubilant Ingrevia Limited, Plot 1-A, Sector 16-A,Institutional Area, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 201301 - India T +91-120-4361000 - F +91-120-4234881 / 84 / 85 / 87 / 95 / 96 [email protected] -www.jubilantingrevia.com 1.4.