Secret War: the Navajo Code Talkers in World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Da Vinci Code

The Da Vinci Code Dan Brown FOR BLYTHE... AGAIN. MORE THAN EVER. Acknowledgments First and foremost, to my friend and editor, Jason Kaufman, for working so hard on this project and for truly understanding what this book is all about. And to the incomparable Heide Lange—tireless champion of The Da Vinci Code, agent extraordinaire, and trusted friend. I cannot fully express my gratitude to the exceptional team at Doubleday, for their generosity, faith, and superb guidance. Thank you especially to Bill Thomas and Steve Rubin, who believed in this book from the start. My thanks also to the initial core of early in-house supporters, headed by Michael Palgon, Suzanne Herz, Janelle Moburg, Jackie Everly, and Adrienne Sparks, as well as to the talented people of Doubleday's sales force. For their generous assistance in the research of the book, I would like to acknowledge the Louvre Museum, the French Ministry of Culture, Project Gutenberg, Bibliothèque Nationale, the Gnostic Society Library, the Department of Paintings Study and Documentation Service at the Louvre, Catholic World News, Royal Observatory Greenwich, London Record Society, the Muniment Collection at Westminster Abbey, John Pike and the Federation of American Scientists, and the five members of Opus Dei (three active, two former) who recounted their stories, both positive and negative, regarding their experiences inside Opus Dei. My gratitude also to Water Street Bookstore for tracking down so many of my research books, my father Richard Brown—mathematics teacher and author—for his assistance with the Divine Proportion and the Fibonacci Sequence, Stan Planton, Sylvie Baudeloque, Peter McGuigan, Francis McInerney, Margie Wachtel, André Vernet, Ken Kelleher at Anchorball Web Media, Cara Sottak, Karyn Popham, Esther Sung, Miriam Abramowitz, William Tunstall-Pedoe, and Griffin Wooden Brown. -

An Introduction to Cryptography, Second Edition Richard A

DISCRETE MATHEMATICS AND ITS APPLICATIONS Series Editor KENNETH H. ROSEN An INTRODUCTION to CRYPTOGRAPHY Second Edition © 2007 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC DISCRETE MATHEMATICS and ITS APPLICATIONS Series Editor Kenneth H. Rosen, Ph.D. Juergen Bierbrauer, Introduction to Coding Theory Kun-Mao Chao and Bang Ye Wu, Spanning Trees and Optimization Problems Charalambos A. Charalambides, Enumerative Combinatorics Henri Cohen, Gerhard Frey, et al., Handbook of Elliptic and Hyperelliptic Curve Cryptography Charles J. Colbourn and Jeffrey H. Dinitz, The CRC Handbook of Combinatorial Designs Steven Furino, Ying Miao, and Jianxing Yin, Frames and Resolvable Designs: Uses, Constructions, and Existence Randy Goldberg and Lance Riek, A Practical Handbook of Speech Coders Jacob E. Goodman and Joseph O’Rourke, Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry, Second Edition Jonathan L. Gross and Jay Yellen, Graph Theory and Its Applications, Second Edition Jonathan L. Gross and Jay Yellen, Handbook of Graph Theory Darrel R. Hankerson, Greg A. Harris, and Peter D. Johnson, Introduction to Information Theory and Data Compression, Second Edition Daryl D. Harms, Miroslav Kraetzl, Charles J. Colbourn, and John S. Devitt, Network Reliability: Experiments with a Symbolic Algebra Environment Leslie Hogben, Handbook of Linear Algebra Derek F. Holt with Bettina Eick and Eamonn A. O’Brien, Handbook of Computational Group Theory David M. Jackson and Terry I. Visentin, An Atlas of Smaller Maps in Orientable and Nonorientable Surfaces Richard E. Klima, Neil P. Sigmon, and Ernest L. Stitzinger, Applications of Abstract Algebra with Maple™ and MATLAB®, Second Edition Patrick Knupp and Kambiz Salari, Verification of Computer Codes in Computational Science and Engineering William Kocay and Donald L. -

The Cultural Contradictions of Cryptography: a History of Secret Codes in Modern America

The Cultural Contradictions of Cryptography: A History of Secret Codes in Modern America Charles Berret Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2019 © 2018 Charles Berret All rights reserved Abstract The Cultural Contradictions of Cryptography Charles Berret This dissertation examines the origins of political and scientific commitments that currently frame cryptography, the study of secret codes, arguing that these commitments took shape over the course of the twentieth century. Looking back to the nineteenth century, cryptography was rarely practiced systematically, let alone scientifically, nor was it the contentious political subject it has become in the digital age. Beginning with the rise of computational cryptography in the first half of the twentieth century, this history identifies a quarter-century gap beginning in the late 1940s, when cryptography research was classified and tightly controlled in the US. Observing the reemergence of open research in cryptography in the early 1970s, a course of events that was directly opposed by many members of the US intelligence community, a wave of political scandals unrelated to cryptography during the Nixon years also made the secrecy surrounding cryptography appear untenable, weakening the official capacity to enforce this classification. Today, the subject of cryptography remains highly political and adversarial, with many proponents gripped by the conviction that widespread access to strong cryptography is necessary for a free society in the digital age, while opponents contend that strong cryptography in fact presents a danger to society and the rule of law. -

Codebreakers

1 Some of the things you will learn in THE CODEBREAKERS • How secret Japanese messages were decoded in Washington hours before Pearl Harbor. • How German codebreakers helped usher in the Russian Revolution. • How John F. Kennedy escaped capture in the Pacific because the Japanese failed to solve a simple cipher. • How codebreaking determined a presidential election, convicted an underworld syndicate head, won the battle of Midway, led to cruel Allied defeats in North Africa, and broke up a vast Nazi spy ring. • How one American became the world's most famous codebreaker, and another became the world's greatest. • How codes and codebreakers operate today within the secret agencies of the U.S. and Russia. • And incredibly much more. "For many evenings of gripping reading, no better choice can be made than this book." —Christian Science Monitor THE Codebreakers The Story of Secret Writing By DAVID KAHN (abridged by the author) A SIGNET BOOK from NEW AMERICAN LIBRARV TIMES MIRROR Copyright © 1967, 1973 by David Kahn All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address The Macmillan Company, 866 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-16109 Crown copyright is acknowledged for the following illustrations from Great Britain's Public Record Office: S.P. 53/18, no. 55, the Phelippes forgery, and P.R.O. 31/11/11, the Bergenroth reconstruction. -

List of Glossary Terms

List of Glossary Terms A Ageofaclusterorfuzzyrule 1054 A correlated equilibrium 3064 Agent 58, 76, 105, 1767, 2578, 3004 Amechanism 1837 Agent architecture 105 Anearestneighbor 790 Agent based models 2940 A social choice function 1837 Agent (or software agent) 2999 A stochastic game 3064 Agent-based computational models 2898 Astrategy 3064 Agent-based model 58 Abelian group 2780 Agent-based modeling 1767 Absolute temperature 940 Agent-based modeling (ABM) 39 Absorbing state 1080 Agent-based simulation 18, 88 Abstract game 675 Aggregation 862 Abstract game of network formation with respect to Aggregation operators 122 irreflexive dominance 2044 Aging 2564, 2611 Abstract game of network formation with respect to path Algebra 2925 dominance 2044 Algebraic models 2898 Accuracy 161, 827 Algorithm 2496 Accuracy (rate) 862 Algorithmic complexity of object x 132 Achievable mate 3235 Algorithmic self-assembly of DNA tiles 1894 Action profile 3023 Allowable set of partners 3234 Action set 3023 Almost equicontinuous CA 914, 3212 Action type 2656 Alphabet of a cellular automaton 1 Activation function 813 ˛-Level set and support 1240 Activator 622 Alternating independent-2-paths 2953 Active membranes 1851 Alternating k-stars 2953 Actors 2029 Alternating k-triangles 2953 Adaptation 39 Amorphous computer 147 Adaptive system 1619 Analog 3187 Additive cellular automata 1 Analog circuit 3260 Additively separable preferences 3235 Ancilla qubits 2478 Adiabatic switching 1998 Anisotropic elements 754 Adjacency matrix 1746, 3114 Annealed law 2564 Adjacent 2864, -

An Introduction to Cryptography, Second Edition Richard A

DISCRETE MATHEMATICS AND ITS APPLICATIONS Series Editor KENNETH H. ROSEN An INTRODUCTION to CRYPTOGRAPHY Second Edition © 2007 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC DISCRETE MATHEMATICS and ITS APPLICATIONS Series Editor Kenneth H. Rosen, Ph.D. Juergen Bierbrauer, Introduction to Coding Theory Kun-Mao Chao and Bang Ye Wu, Spanning Trees and Optimization Problems Charalambos A. Charalambides, Enumerative Combinatorics Henri Cohen, Gerhard Frey, et al., Handbook of Elliptic and Hyperelliptic Curve Cryptography Charles J. Colbourn and Jeffrey H. Dinitz, The CRC Handbook of Combinatorial Designs Steven Furino, Ying Miao, and Jianxing Yin, Frames and Resolvable Designs: Uses, Constructions, and Existence Randy Goldberg and Lance Riek, A Practical Handbook of Speech Coders Jacob E. Goodman and Joseph O’Rourke, Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry, Second Edition Jonathan L. Gross and Jay Yellen, Graph Theory and Its Applications, Second Edition Jonathan L. Gross and Jay Yellen, Handbook of Graph Theory Darrel R. Hankerson, Greg A. Harris, and Peter D. Johnson, Introduction to Information Theory and Data Compression, Second Edition Daryl D. Harms, Miroslav Kraetzl, Charles J. Colbourn, and John S. Devitt, Network Reliability: Experiments with a Symbolic Algebra Environment Leslie Hogben, Handbook of Linear Algebra Derek F. Holt with Bettina Eick and Eamonn A. O’Brien, Handbook of Computational Group Theory David M. Jackson and Terry I. Visentin, An Atlas of Smaller Maps in Orientable and Nonorientable Surfaces Richard E. Klima, Neil P. Sigmon, and Ernest L. Stitzinger, Applications of Abstract Algebra with Maple™ and MATLAB®, Second Edition Patrick Knupp and Kambiz Salari, Verification of Computer Codes in Computational Science and Engineering William Kocay and Donald L. -

Codebreakers

Some of the things you will learn in THE CODEBREAKERS • How secret Japanese messages were decoded in Washington hours before Pearl Harbor. • How German codebreakers helped usher in the Russian Revolution. • How John F. Kennedy escaped capture in the Pacific because the Japanese failed to solve a simple cipher. • How codebreaking determined a presidential election, convicted an underworld syndicate head, won the battle of Midway, led to cruel Allied defeats in North Africa, and broke up a vast Nazi spy ring. • How one American became the world's most famous codebreaker, and another became the world's greatest. • How codes and codebreakers operate today within the secret agencies of the U.S. and Russia. • And incredibly much more. "For many evenings of gripping reading, no better choice can be made than this book." —Christian Science Monitor THE Codebreakers The Story of Secret Writing By DAVID KAHN (abridged by the author) A SIGNET BOOK from NEW AMERICAN LIBRARV TIMES MIRROR Copyright © 1967, 1973 by David Kahn All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address The Macmillan Company, 866 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-16109 Crown copyright is acknowledged for the following illustrations from Great Britain's Public Record Office: S.P. 53/18, no. 55, the Phelippes forgery, and P.R.O. 31/11/11, the Bergenroth reconstruction. -

Stealing-The-Network-How-To-Own-A

363_Web_App_FM.qxd 12/19/06 10:46 AM Page ii 384_STS_FM.qxd 1/3/07 10:04 AM Page i Visit us at www.syngress.com Syngress is committed to publishing high-quality books for IT Professionals and delivering those books in media and formats that fit the demands of our cus- tomers. We are also committed to extending the utility of the book you purchase via additional materials available from our Web site. SOLUTIONS WEB SITE To register your book, visit www.syngress.com/solutions. Once registered, you can access our [email protected] Web pages. There you may find an assortment of value-added features such as free e-books related to the topic of this book, URLs of related Web sites, FAQs from the book, corrections, and any updates from the author(s). ULTIMATE CDs Our Ultimate CD product line offers our readers budget-conscious compilations of some of our best-selling backlist titles in Adobe PDF form. These CDs are the perfect way to extend your reference library on key topics pertaining to your area of exper- tise, including Cisco Engineering, Microsoft Windows System Administration, CyberCrime Investigation, Open Source Security, and Firewall Configuration, to name a few. DOWNLOADABLE E-BOOKS For readers who can’t wait for hard copy, we offer most of our titles in download- able Adobe PDF form. These e-books are often available weeks before hard copies, and are priced affordably. SYNGRESS OUTLET Our outlet store at syngress.com features overstocked, out-of-print, or slightly hurt books at significant savings. SITE LICENSING Syngress has a well-established program for site licensing our e-books onto servers in corporations, educational institutions, and large organizations. -

The Da Vinci Code

The Da Vinci Code Dan Brown FOR BLYTHE... AGAIN. MORE THAN EVER. Acknowledgments First and foremost, to my friend and editor, Jason Kaufman, for working so hard on this project and for truly understanding what this book is all about. And to the incomparable Heide Lange—tireless champion of The Da Vinci Code, agent extraordinaire, and trusted friend. I cannot fully express my gratitude to the exceptional team at Doubleday, for their generosity, faith, and superb guidance. Thank you especially to Bill Thomas and Steve Rubin, who believed in this book from the start. My thanks also to the initial core of early in-house supporters, headed by Michael Palgon, Suzanne Herz, Janelle Moburg, Jackie Everly, and Adrienne Sparks, as well as to the talented people of Doubleday's sales force. For their generous assistance in the research of the book, I would like to acknowledge the Louvre Museum, the French Ministry of Culture, Project Gutenberg, Bibliothèque Nationale, the Gnostic Society Library, the Department of Paintings Study and Documentation Service at the Louvre, Catholic World News, Royal Observatory Greenwich, London Record Society, the Muniment Collection at Westminster Abbey, John Pike and the Federation of American Scientists, and the five members of Opus Dei (three active, two former) who recounted their stories, both positive and negative, regarding their experiences inside Opus Dei. My gratitude also to Water Street Bookstore for tracking down so many of my research books, my father Richard Brown—mathematics teacher and author—for his assistance with the Divine Proportion and the Fibonacci Sequence, Stan Planton, Sylvie Baudeloque, Peter McGuigan, Francis McInerney, Margie Wachtel, André Vernet, Ken Kelleher at Anchorball Web Media, Cara Sottak, Karyn Popham, Esther Sung, Miriam Abramowitz, William Tunstall-Pedoe, and Griffin Wooden Brown. -

Report of Flintlock Operation

Uto. ER J^IFTH AMPHIBIOUS FORCE REPORT OF FLINTLOCK OPERATION DOWNGRADED AT 3 YERR INTERVALS; RE©: L-Ui Uvii.W COMBINED ARMS RESEARCH LIBRARY FORT LEAVENWORTH, KS 3 1695 00839 7424 GENCENTPAC AG. Dato— 19 April 1944. HEADQUARTERS UNITED ^TATFg ARMY EOJ ircc rcLLXRAJL PACIFIC AREA ****** toasts mm mm mm AG 052/285 19 April 1944. SUBJECT: 'Transmittal Of Report of FlintJock Operation - 5thPhibFor. TO : Commandant, Command and General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The inclosed report is forwarded for your information: For the Commanding General: 0. M. THOMPSONJ Colonel, AGD, 1 Incl: Adjutant General. Report of Flintlock Operation (Reg. No. 30) rrn.«n£ instroictGrs (pile Ho Sign Below _ _ Date ^air.s --- -55W?55i£T* naj Dun i/iB f ^ - )• ft UUidU Cii 'w -LASIIPikC * In^ ^st %- AG. PS&1P1 ft 19 Asfil 19AL. HEADQUARTERS jfe^TfS ARMVfPi## CENl^LfflJnC AREA APO 958 AG (£2/285 19 April 1944. SUBJECT! Transmittal of Keport of Flintlock Operation - 5tiPhibFor. TO i Commandant, Coomsnd end General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The inclosed report is forwarded for your information: For the Commanding Generals O.'I. THOMPSON, Colonel, A CD, 1 IBCIJ Adjutant General. Keport of Flintlock Operation C^®S« No. 30} C5A/A16--3(3) . JOINT 'EXPEDITE jiRY-'FORCE- (TF 51) V. OFFICE OF TEE COMMANDER, - .' Serial 00189 U.S.S. ROCKY MOUNT, Flagship, February 25, 1944 f% $ T5 8 IT *<• . « h 3 Qfi i '1 '4J * ... K a;V ¥ ... J . ^ i ' From: Commander Joint Expeditionary Force, FLDTTLOCK, (Commander FIFTH Amphibious Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet); To: Commander in Chief, U. -

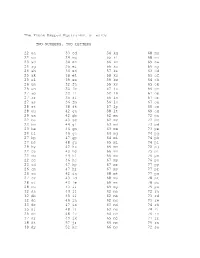

The Phone Keypad Equivalent of Words TWO NUMBERS, TWO

The Phone Keypad Equivalent of words TWO NUMBERS, TWO LETTERS 22 aa 33 ed 54 kg 68 nu 22 ac 34 eg 55 kl 68 nv 23 ad 34 eh 56 km 69 nw 24 ag 35 el 56 ko 69 ny 24 ah 36 en 57 ks 63 od 25 ak 38 et 58 ku 63 of 25 al 39 ex 59 kw 64 oh 26 am 32 fa 59 ky 65 ok 26 an 33 fe 52 la 66 on 27 ap 33 ff 52 lb 67 op 27 ar 35 fl 56 ln 67 or 27 as 36 fm 56 lo 67 os 28 at 38 ft 57 lp 69 ow 28 au 42 ga 58 lt 69 ox 29 ax 42 gb 62 ma 72 pa 22 ba 43 ge 62 mc 72 pc 22 bc 44 gi 63 md 73 pd 23 be 46 gm 63 me 73 pe 24 bi 46 go 64 mg 74 pg 27 bp 47 gp 64 mi 74 ph 27 bs 48 gu 65 ml 74 pi 29 by 42 ha 66 mm 75 pj 22 ca 43 he 66 mn 75 pl 22 cb 44 hi 66 mo 76 pm 22 cc 46 ho 67 mp 76 po 23 cd 47 hp 67 mr 77 pp 26 cm 47 hr 67 ms 77 pr 26 co 42 ia 68 mt 77 ps 27 cs 43 id 68 mu 78 pt 28 ct 43 ie 69 mx 78 pu 28 cu 43 if 69 my 79 px 32 da 44 ii 62 na 72 ra 32 db 45 il 62 nb 73 rd 32 dc 46 in 62 nc 73 re 33 de 47 is 63 nd 74 rh 35 dj 48 it 63 ne 74 ri 36 do 48 iv 64 nh 76 rn 37 dr 49 ix 65 nj 77 rr 38 dt 57 jr 66 nm 79 rx 39 dy 52 kc 66 no 72 sa Phone Number Words--Walton--Page 2 72 sc 73 sd 73 se 73 sf 76 so 78 st 79 sw 82 ta 82 tb 86 tn 86 to 88 tt 88 tv 89 tx 84 uh 85 uk 86 un 87 up 87 us 88 ut 88 uv 82 va 82 vc 83 vd 84 vi 87 vp 88 vt 92 wa 93 we 94 wi 95 wk 97 wp 98 wt 98 wv 99 wy 94 xi 98 xv 99 xx 93 yd 97 yr THREE NUMBERS, THREE LETTERS 222 aaa 222 abc 223 ace 232 ada 235 adj 232 aec 222 aba 223 abe 228 act 233 add 236 ado 235 afl Phone Number Words--Walton--Page 3 238 aft 296 awn 289 buy 288 cut 393 dye 322 fcc 243 age 293 axe 293 bye 298 cwt 327 ear 332 fda 246 ago -

Codes: the Guide to Secrecy from Ancient to Modern Times Richard A

Codes The Guide to Secrecy from Ancient to Modern Times DISCRETE MATHEMATICS and ITS APPLICATIONS Series Editor Kenneth H. Rosen, Ph.D. Juergen Bierbrauer, Introduction to Coding Theory Kun-Mao Chao and Bang Ye Wu, Spanning Trees and Optimization Problems Charalambos A. Charalambides, Enumerative Combinatorics Charles J. Colbourn and Jeffrey H. Dinitz, The CRC Handbook of Combinatorial Designs Steven Furino, Ying Miao, and Jianxing Yin, Frames and Resolvable Designs: Uses, Constructions, and Existence Randy Goldberg and Lance Riek, A Practical Handbook of Speech Coders Jacob E. Goodman and Joseph O’Rourke, Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry, Second Edition Jonathan Gross and Jay Yellen, Graph Theory and Its Applications Jonathan Gross and Jay Yellen, Handbook of Graph Theory Darrel R. Hankerson, Greg A. Harris, and Peter D. Johnson, Introduction to Information Theory and Data Compression, Second Edition Daryl D. Harms, Miroslav Kraetzl, Charles J. Colbourn, and John S. Devitt, Network Reliability: Experiments with a Symbolic Algebra Environment Derek F. Holt with Bettina Eick and Eamonn A. O’Brien, Handbook of Computational Group Theory David M. Jackson and Terry I. Visentin, An Atlas of Smaller Maps in Orientable and Nonorientable Surfaces Richard E. Klima, Ernest Stitzinger, and Neil P. Sigmon, Abstract Algebra Applications with Maple Patrick Knupp and Kambiz Salari, Verification of Computer Codes in Computational Science and Engineering William Kocay and Donald L. Kreher, Graphs, Algorithms, and Optimization Donald L. Kreher and Douglas R. Stinson, Combinatorial Algorithms: Generation Enumeration and Search Charles C. Lindner and Christopher A. Rodgers, Design Theory Alfred J. Menezes, Paul C. van Oorschot, and Scott A.