Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 07:56:16AM Via Free Access Chapter 2 the Image of Piety at the Dawn of Iconoclasm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresh Pigmeat and Certain Meat-Based Pork Products ;

21 . 8 . 87 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 238/31 COMMISSION DECISION of 28 July 1987 concerning certain protection measures relating to classical swine fever in Belgium (87/435/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION : Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Article 1 Having regard to Council Directive 64/432/EEC of 26 June 1964 on animal health problems affecting intra The Kingdom of Belgium shall not send to other Community trade in bovine animals and swine ('), as last Member States live pigs coming from those parts of their amended by Directive 87/231 /EEC (2), and in particular territory described in the Annex . Article 9 thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 72/461 /EEC of 12 Article 2 December 1972 on health problems affecting intra Community trade in fresh meat (3), as last amended by 1 . The Kingdom of Belgium shall not send to other Directive 87/231 /EEC, and in particular Article 8 thereof, Member States fresh pigmeat coming from those part of their territory described in the Annex, and fresh pigmeat Whereas several outbreaks of classical swine fever have obtained from pigs coming from those parts of Belgium occurred in parts of Belgium outside the area where vacci but slaughtered elsewhere . nation is carried out on a routine basis ; 2 . The meat referred to in paragraph 1 shall bear either Whereas these outbreaks are liable to endanger the herds the national stamp or the stamp prescribed by Article 5a of other Member States, in view of the trade in live pigs, of Directive 72/461 /EEC . -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Gothic Churches in Paris St Gervais Et St Protais Image Matching 3D Reconstruction to Understand the Vaults System Geometry

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W4, 2015 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25-27 February 2015, Avila, Spain GOTHIC CHURCHES IN PARIS ST GERVAIS ET ST PROTAIS IMAGE MATCHING 3D RECONSTRUCTION TO UNDERSTAND THE VAULTS SYSTEM GEOMETRY M.Capone a, , M. Campi b, R. Catuogno c a DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] b DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] c DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: Structure from Motion, Image Matching, 3D Modeling, Ribbed Vaults, Gothic Flamboyant, 3D reconstruction. ABSTRACT: This paper is part of a research about ribbed vaults systems in French Gothic Cathedrals. Our goal is to compare some different gothic cathedrals to understand the complex geometry of the ribbed vaults. The survey isn't the main objective but it is the way to verify the theoretical hypotheses about geometric configuration of the flamboyant churches in Paris. The survey method's choice generally depends on the goal; in this case we had to study many churches in a short time, so we chose 3D reconstruction method based on image dense stereo matching. This method allowed us to obtain the necessary information to our study without bringing special equipment, such as the laser scanner. The goal of this paper is to test image matching 3D reconstruction method in relation to some particular study cases and to show the benefits and the troubles. -

Workshop: Cannibalism and the Eucharist in Medieval Literature

Humanities Research Centre Workshop: Cannibalism and the Eucharist in medieval literature Wednesday 15th June, 5pm-7pm Wolfson 3 Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen, Man of Sorrows , first half of 16th century, oil on panel, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp. Contacts @medievalwarwick Jane Sinnett-Smith: [email protected] Louise Campion: [email protected] Humanities Research Centre There is one Universal Church of the faithful, outside of which there is absolutely no salvation. In which there is the same priest and sacrifice, Jesus Christ, whose body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine; the bread being changed (transsubstantiatio) by divine power into the body, and the wine into the blood, so that to realize the mystery of unity we may receive of Him what He has received of us. [Canon 1, the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215, Medieval Sourcebook http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/lateran4.asp ] The process of transubstantiation, by which the bread and wine of the Eucharist is transformed into the body and blood of Christ, would have been familiar to all medieval Christians. Yet even as it formed an essential part of Christian ritual and an important means of constituting the Christian community, it remained a point of contentious debate and profound anxiety for many medieval writers. What did it mean to eat the human flesh of God? To digest it? How was this consumption different to the consumption of animal flesh, or the bodies of other humans? What does eating God do to the body of the consumer? From representations of the Eucharist in devotional literature in which the celebrant explicitly consumes flesh and blood to tales of cannibals in far-off lands whose customs eerily echo the Christian rite, throughout the literatures of medieval Europe these questions were not just a source of doctrinal anxiety, but a spur to imaginative reflections on and reformulations of a cannibal Eucharist. -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

Belgium-Luxembourg-6-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges & Antwerp & Western Flanders Eastern Flanders p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Western Wallonia p182 The Ardennes p203 Luxembourg p242 #_ THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Helena Smith, Andy Symington, Donna Wheeler PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Belgium BRUSSELS . 34 Antwerp to Ghent . 164 & Luxembourg . 4 Around Brussels . 81 Westmalle . 164 Belgium South of Brussels . 81 Hoogstraten . 164 & Luxembourg Map . 6 Southwest of Brussels . 82 Turnhout . 164 Belgium North of Brussels . 82 Lier . 166 & Luxembourg’s Top 15 . 8 Mechelen . 168 Need to Know . 16 BRUGES & WESTERN Leuven . 173 First Time . 18 FLANDERS . 83 Leuven to Hasselt . 177 Hasselt & Around . 178 If You Like . 20 Bruges (Brugge) . 85 Tienen . 178 Damme . 105 Month by Month . 22 Hoegaarden . 179 The Coast . 106 Zoutleeuw . 179 Itineraries . 26 Knokke-Heist . 107 Sint-Truiden . 180 Travel with Children . 29 Het Zwin . 107 Tongeren . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 De Haan . 107 Zeebrugge . 108 Lissewege . 108 WESTERN Ostend (Oostende) . 108 WALLONIA . 182 MATT MUNRO /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY MUNRO MATT Nieuwpoort . 114 Tournai . 183 Oostduinkerke . 114 Pipaix . 188 St-Idesbald . 115 Aubechies . 189 De Panne & Adinkerke . 115 Belœil . 189 Veurne . 115 Lessines . 190 Diksmuide . 117 Enghien . 190 Beer Country . 117 Mons . 190 Westvleteren . 117 Waterloo Battlefield . 194 Woesten . 117 Nivelles . 196 Watou . 117 Louvain-la-Neuve . 197 CHOCOLATE LINE, BRUGES P103 Poperinge . 118 Villers-la-Ville . 197 Ypres (Ieper) . 119 Charleroi . 198 Ypres Salient . 123 Thuin . 199 HELEN CATHCART /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY HELEN CATHCART Comines . 124 Aulne . 199 Kortrijk . 125 Ragnies . 199 Oudenaarde . -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/09/2021 07:17:43PM Via Free Access Chapter 1 the Cult of Saint Leonard at Zoutleeuw

Ruben Suykerbuyk - 9789004433106 Downloaded from Brill.com10/09/2021 07:17:43PM via free access Chapter 1 The Cult of Saint Leonard at Zoutleeuw Saint Leonard’s Altarpiece In July 1476, the churchwardens of Zoutleeuw gathered in a tavern to discuss commissioning an altarpiece dedicated to Saint Leonard. After their meeting, they placed an order in Brussels, and the work was finished in March 1478. The churchwardens again travelled to Brussels to settle the payment, and the retable was shipped to Zoutleeuw via Mechelen.1 The subject and the style, as well as the presence of Brussels quality marks on both the sculpture and the case of the oldest retable preserved in the Zoutleeuw church today (fig. 8), confirm that it is the very same one that was commissioned in 1476.2 Saint Leonard, the Christian hero of the altarpiece, lived in Merovingian France around the year 500. His hagiography identi- fies his parents as courtiers to King Clovis and states that he had been baptized and instructed in Christian faith by Saint Remigius, archbishop of Reims. Leonard quickly won Clovis’ goodwill, and was granted many favors by him. Not only was he allowed to free the pris- oners he visited, he was also offered a bishopric. However, preferring solitude and prayer he refused the honor and instead went to live in a forest near Limoges, where he preached and worked miracles. One of these wonders involved the pregnant queen, who had joined her husband on a hunting party in the woods and was suddenly seized by labor pains. Leonard prayed on her behalf for safe delivery. -

Flying Buttresses • Openings and Spans • Bar Tracery and Linear Elements • Large Scale Construction and Transmission of Knowledge

HA2 Autumn 2005 Gothic Architecture: design and history Outline • Main design issues and innovations • Structural outline • Chronological development • Classical styles (France) • Outside the canon • Gothic in the UK • Case study: Burgos Cathedral Gothic Architecture: design and history 2 Gothic Architecture: design and history Dimitris Theodossopoulos 1 HA2 Autumn 2005 Main design issues • Definition – a sharp change from Romanesque? (St Denis 1130) • Major elements pre-existing (ribs and shafts, pointed arches, cross vaults) • Composition and scale • Light and height • Role of patrons (royal vs. secular foundations) and cathedral buildings • Strong technological input • European regional characteristics • Decline: decorative character and historical reasons Gothic Architecture: design and history 3 Main design issues Gothic Architecture: design and history 4 Gothic Architecture: design and history Dimitris Theodossopoulos 2 HA2 Autumn 2005 Technological innovations • Dynamic composition • Dynamic equilibrium • Linearity – origin in Norman timber technology? • Role of the ribs (and shafts) • Spatial flexibility of cross vaults – use of pointed arch • Flying buttresses • Openings and spans • Bar tracery and linear elements • Large scale construction and transmission of knowledge Gothic Architecture: design and history 5 The role of geometry Gothic Architecture: design and history 6 Gothic Architecture: design and history Dimitris Theodossopoulos 3 HA2 Autumn 2005 Light Contrast Durham Cathedral (1093-1133) and Sainte Chapelle in Paris -

Linkebeek 10.23%

Geografische indicatoren (gebaseerd op Census 2011) De referentiedatum van de Census is 01/01/2011. Filters: Woningen gebouwd vanaf 1991 België Gewest Provincie Arrondissement Gemeente Sint-Gillis 2.84% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Schaarbeek 3.00% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Colfontaine 3.54% Vlaams Gewest Provincie Limburg Arrondissement Tongeren Herstappe 3.57% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Vorst (Brussel-Hoofdstad) 3.78% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Luik Luik 4.24% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Watermaal-Bosvoorde 4.41% Farciennes 4.44% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Charleroi Charleroi 4.49% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Sint-Joost-ten-Node 5.36% Provincie Namen Arrondissement Philippeville Doische 5.39% Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Boussu 5.46% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Luik Saint-Nicolas (Luik) 6.01% Arrondissement Bergen Dour 6.28% Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Thuin Erquelinnes 6.34% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Elsene 6.65% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Quaregnon 6.71% Anderlecht 6.81% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Ganshoren 6.99% Verviers 7.06% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Verviers Dison 7.18% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Etterbeek 7.32% Flémalle 7.36% Provincie -

Politiezone LANDEN – LINTER

Politiezone LANDEN – LINTER - ZOUTLEEUW 1 2 JAARVERSLAG 2015 Politiezone LAN 5390 Landen – Linter – Zoutleeuw PZ LAN 5390 Populierendreef 2 3400 Landen Tel. : 011/884 884 Fax: 011/88 33 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.lokalepolitie.be/5390 3 INHOUD Voorwoord ………………………………………………………………………………….5 Beleid ………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Personeel …………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Financiën ……………………………………………………………………………………..13 Heugelijke dagen voor de PZ LAN …………………………………………………………..17 Werking Politionele cijfers …………………………………………………………………………….23 Verkeer ………………………………………………………………………………………28 Diefstallen ……………………………………………………………………………………39 Verdovende middelen ………………………………………………………………………..49 Prorela ………………………………………………………………………………………..51 Slachtofferbejegening ………………………………………………………………………..51 Milieu ………………………………………………………………………………………..52 Contactgegevens ……………………………………………………………………………..53 4 VOORWOORD Nooit hadden we het ons in het hoofd gehaald. We hadden het zelfs niet kunnen en willen denken. “De inhuldiging van het nieuw politiehuis met langs alle zijden van de site zwaar bewapende politie-inspecteurs”. Was dit in Landen? En met dit contrast van feest en dreiging zal 2015 in ons geheugen gegrift blijven. 2015 was voor de lokale politie van de PZ LAN het jaar van de grote metamorfose, tenminste op het vlak van huisvesting. Het nieuw commissariaat op Hasco was een feit en burgers en medewerkers zouden voortaan krijgen waar ze recht op hadden, namelijk een aangepaste ruimte waar dienstverlening een ander gezicht kon krijgen. En ondanks een veelvoud -

Embodied Piety Sacrament Houses and Iconoclasm in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries

bmgn - Low Countries Historical Review | Volume 131-1 (2016) | pp. 36-58 Embodied Piety Sacrament Houses and Iconoclasm in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries anne-laure van bruaene On the eve of the Beeldenstorm, a great number of churches in the Low Countries had a sacrament house, a shrine for the Corpus Christi, often metres high. These monstrance-like tabernacles were nearly all destroyed by iconoclasts between 1566 and 1585. This essay discusses the dialectics between the construction and destruction of sacrament houses before and after the Beeldenstorm. It argues against a strict divide between material devotion and spiritual belief by highlighting the intertwining of Catholic and Calvinist embodied pieties. Fuelled by their opposing conceptions of the Eucharist, Catholic devotees and Protestant iconoclasts both engaged with sacrament houses and other expressions of the Corpus Christi devotion (processions, miracle cults et cetera) in a deliberate and intensely physical manner. Belichaamde vroomheid. Sacramentshuizen en iconoclasme in de zestiende-eeuwse Nederlanden Aan de vooravond van de Beeldenstorm stond in heel wat kerken in de Nederlanden een sacramentshuis, een vaak metershoge toren met het uiterlijk van een reusachtige monstrans, waarin het Corpus Christi werd tentoongesteld. Deze tabernakels werden haast allemaal vernield door iconoclasten tussen 1566 en 1585. Dit artikel bestudeert het samenspel tussen het optrekken en afbreken van sacramentshuizen voor en na de Beeldenstorm. De centrale stelling luidt dat we af moeten van een strikte scheiding tussen materiële devotie en spiritueel geloof. Zowel katholieken als calvinisten beleefden hun geloof op een belichaamde manier en hun handelingen waren steeds verweven. Vrome katholieke leken en protestantse beeldenstormers hadden sterk conflicterende ideeën over de eucharistie, maar juist daarom gingen ze op een heel bewuste en uiterst lichamelijke manier om met de sacramentshuizen en andere uitingen van sacramentsvroomheid zoals ommegangen en mirakelcultussen. -

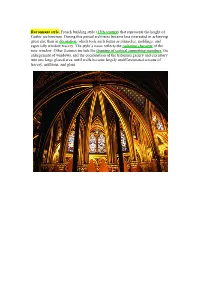

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century.