Role of Accounting Practices in the Disempowerment of the Coahuiltecan Indians Sarah A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coahuilteco, the Language Was Coahuilteco, the Language Group Was Coahuiltecan

1. Description 1.1 Name of society, language, and language family: The society is Coahuilteco, the language was Coahuilteco, the language group was Coahuiltecan. What languages fall under the Coahuiltecan Family and whether or not it is an actual language family are still under debate. Originally, Coahuilteco was one of several distinctly different languages spoken throughout southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. Following the arrival of Spanish Missionaries, Coahuilteco became a lingua franca in the area. There are no known speakers of the language today.1 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): Coahuilteco does not have an ISO Code. 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): Inland southern Texas. 29.3327° N, 98.4553° W.2 The Coahuilteco ranged across the entirety of texas between San Antonio and the Rio Grande as well as into the Mexican province of Coahuila. 1.4 Brief history: The early history of the Coahuiltecans is unknown2. They were first encountered in the 1500s by the Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca3. In the 1600s Franciscan missions were established in Nadadores, San Antonio, and along the Rio Grande for the express purpose of converting the Coahuilteco3. In 1690 there were an estimated 15000 Coahuilteco in over 200 scattered bands. By the late 19th century, disease, attacks by other tribes, and cultural integration had shrunk that number to two or three tribes on the southern side of the Rio Grande, none of whom spoke Coahuilteco3. 1.5 Influence of missionaries/schools/governments/powerful neighbors: The Coahuilteco were decimated by diseases brought by Spanish missionaries as well as assimilation into Mexican culture and attacks by Comanche and Apaches from the north3. -

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park (PDF)

A fact sheet from 2017 Marcia Argust/The Pew Charitable Trusts Repairing door beams at Mission San José—one of the four protected within the park—is part of a $7.4 million maintenance backlog. Carol Highsmith/Library of Congress San Antonio Missions National Historical Park Texas Overview San Antonio Missions National Historical Park is one of America’s cultural treasures, designated in 2015 as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The park preserves four Spanish frontier missions built in the 1700s for Franciscan friars who hoped to convert the Native Americans to Catholicism. Over time, the Spanish and local tribes built a new culture in what is now South Texas. Drawing more than a million visitors a year, the park is also a boon to San Antonio’s economy. But it faces a maintenance backlog of $7.3 million that includes restoring the missions and key infrastructure. Maintenance challenges The park’s most urgent repairs are to its historic buildings and visitor center. The center is more than 20 years old and needs more than a half-million dollars to update its interpretive displays. Nearly $400,000 is needed to repair the office and sacristy of the Franciscan father-president, who oversaw development of the missions. A compound where Native Americans lived, and the walls that encircle it, also requires restoration at a cost of $600,000. Repair needs go beyond the buildings that define San Antonio Missions. Several parking lots are showing their age and require almost a million dollars to resurface, and its water and communication systems are deteriorating and must be replaced. -

Sod Poodles Announce 2021 Season Schedule Sod Poodles to Host 60 Home Games at HODGETOWN in 2021, Home Opener Set for Tuesday, May 18

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected] Sod Poodles Announce 2021 Season Schedule Sod Poodles To Host 60 Home Games at HODGETOWN in 2021, Home Opener Set For Tuesday, May 18 AMARILLO, Texas (Feb 18, 2021) — Major League Baseball announced today the complete Sod Poodles schedule for the 2021 Minor League Baseball season. The season comprises 120 regular-season games, 60 at home and 60 on the road, and will begin on Tuesday, May 4 and run through Sunday, September 19. The Sod Poodles 2021 campaign begins on the road with a Championship rematch against the Tulsa Drillers, Double-A affiliate of the Los Angeles Dodgers. The 2021 home opener at HODGETOWN is scheduled for Tuesday, May 18 against the Midland RockHounds, Double-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics. “We couldn’t be more excited to announce to our community, the best fans in baseball, that the wait is over and Sod Poodles baseball is officially coming back to HODGETOWN this May,” said Sod Poodles President and General Manager Tony Ensor. “The 2019 season was the storybook year we all dreamt about and now it’s time to create new memories and see the future Major League stars of our new MLB affiliate team, the Arizona Diamondbacks. The future of baseball and entertainment in Amarillo is bright with the return of the Sod Poodles this summer and our new 10-year partnership with the D-backs!” In 2021, each team in the Double-A Central will play a total of 20 series, 10 at home and 10 on the road. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Historic Indian Groups of the Choke Canyon Reservoir and Surrounding Area, Southern Texas

Volume 1981 Article 24 1981 Historic Indian Groups of the Choke Canyon Reservoir and Surrounding Area, Southern Texas T. N. Campbell Center for Archaeological Research T. J. Campbell Center for Archaeological Research Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Campbell, T. N. and Campbell, T. J. (1981) "Historic Indian Groups of the Choke Canyon Reservoir and Surrounding Area, Southern Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1981, Article 24. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.1981.1.24 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1981/iss1/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Historic Indian Groups of the Choke Canyon Reservoir and Surrounding Area, Southern Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1981/iss1/24 HISTORIC INDIAN GROUPS OF THE CHOKE CANYON RESERVOIR AND SURROUNDING AREA, SOUTHERN TEXAS T. -

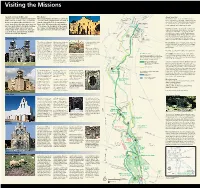

Visiting the Missions

Visiting the Missions Spanish Colonial Architecture The Alamo About Your Visit Early missions were unwalled communities Mission San Antonio de Valero is commonly The visitor center—located at 6701 San José built of wood or adobe. Later, as tensions called the Alamo (right). Founded in 1718, it Drive, San Antonio, TX 78214—and missions are between northern tribes and mission resi was the first mission on the San Antonio open daily except Thanksgiving Day, December dents grew, these structures were encircled River. After 106 years as the sole caretaker 25, and January 1. The park has picnic tables. Food, camping, and lodging are nearby. by stone walls. Directed by skilled artisans of the Alamo, the Daughters of the Repub recruited from New Spain, the mission lic of Texas now manages this state historic For Your Safety Be careful: walks, ramps, and Indians built their communities. They pre site under the Texas General Land Office. steps can be uneven and slippery. • Avoid fire served the basic Spanish model, modified ants; stay on sidewalks. • Lock your car with as frontier conditions dictated. valuables out of sight. • Flash floods are com ALL PHOTOS NPS mon and deadly. When the San Antonio River rises, the mission trail south of Mission San José Concepción is closed. Don’t pass barriers that announce water on roads. Be cautious at water crossings. The mission of Nuestra Missionaries worked to conversions when Indi- Be Considerate Stay off fragile stone walls. The Señora de la Purísima replace traditional ans took the sacra- missions are places of worship. Do not disrupt Concepción was trans- Indian rituals with reli- ments. -

Table 5-4. the North American Tribes Coded for Cannibalism by Volhard

Table 5-4. The North American tribes coded for cannibalism by Volhard and Sanday compared with all North American tribes, grouped by language and region See final page for sources and notes. Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. Family Group or Dialect Culture No. Language 1. Tribes with reports of cannibalism in Volhard, by region and language Language groups found mainly in the North and West Western Nadene Athapascan Northern Athapascan 798 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Chipewayan Northern ND7 Tschipewayan 799 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Slave Northern ND14 128 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Yellowknife Northern ND14 Subarctic Canada Northwest Salishan Coast Salish Bella Coola Bella Coola British NE6 132 Bilchula, Bilqula 795 Coast Columbia Northwest Penutian Tsimshian Tsimshian Tsimshian British NE15 Tsimschian 793 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Helltsuk Helltsuk British NE5 Heiltsuk 794 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Kwakiutl Kwakiutl British NE10 Kwakiutl* 792, 96, 97 Coast Columbia California Penutian Maidun Maidun Nisenan California NS15 Nishinam* 809, 810 California Yukian Yuklan Yuklan Wappo California NS24 Wappo 808 Language groups found mainly in the Plains Plains Sioux Dakota West Central Plains Sioux Dakota Assiniboin Assiniboin Prairie NF4 Dakota 805 Plains Sioux Dakota Gros Ventre Gros Ventre West Central NQ13 140 Plains Sioux Dakota Miniconju Miniconju West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Santee Santee West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Teton Teton West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Yankton Yankton West Central NQ11 Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. -

2009 UTSA Roadrunners Baseball Media Guide

2009 UTSA Roadrunners Baseball Media Guide Quick Facts Table of Contents General Introduction Institution ___________ The University of Texas at San Antonio Media information ____________________________________ 2 Nickname __________________________________ Roadrunners goUTSA.com _________________________________________ 3 Colors ______________ Orange (1665), navy blue (289) & white 2009 season outlook _________________________________ 4-6 Founded __________________________________________ 1969 2009 schedule ________________________________________ 7 Enrollment _______________________________________28,534 2009 rosters ________________________________________ 8-9 President ______________________________Dr. Ricardo Romo Roadrunner Field ____________________________________ 10 Athletics Director ___________________________ Lynn Hickey Wolff Stadium _______________________________________ 11 Athletics phone __________________________ 210/458-4161 Ticket & camp information ____________________________ 12 Ticket office phone _______________________ 210/458-8872 Affiliation ______________________________ NCAA Division I Meet The Roadrunners Conference ___________________________________ Southland Returnee bios _____________________________________ 14-29 Coaching Staff Newcomer bios ___________________________________ 30-32 Head coach _______________ Sherman Corbett (ninth season) UTSA Baseball award winners _________________________ 33 Record at UTSA (seasons) ________________ 250-213 (eight) Head Coach Sherman Corbett ______________________ -

PD Commons PD Books PD Commons EARLY EXPLORATION/ and MISSION ESTABLISHMENT/ in TEXAJ"

PD Commons PD Books PD Commons EARLY EXPLORATION/ AND MISSION ESTABLISHMENT/ IN TEXAJ" PD Books PD Commons fc 8 w Q fc O 8 fc 8 w G w tn H U5 t-i EARLY EXPLORATIONS AND MISSION ESTABLISHMENTS IN TEXAS BY EDWARD W. HEUSINQER, F.R.Q.S. Illustrated With Original Photographs Maps and Plans THE NAYLOR COMPANY SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS 1936 PD Books PD Commons EARLY EXPLORATIONS AND MISSION ESTABLISHMENTS IN TEXAS BY EDWARD W. HEUSINGER, F.R.Q.S. Illustrated With Original Photographs Maps and Plans THE NAYLOR COMPANY SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS 1936 PD Books PD Commons Copyright, 1936 THE NAYI.OR COMPANY Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. V This book is dedicated to the memory of the Franciscan Missionaries: PR. DAMIAN MASSANET FR. ANTONIO DE SAN BUENAVENTURA Y OLIVARES FR. YSIDRO FELIX DE ESPINOSA FR. ANTONIO MARGIL DE JESUS FR. BARTHOLOME GARCIA and their many intrepid co-workers who unselfishly gave their labor and their lives that Texas might enjoy the heritage of Christianity. PD Books PD Commons INTRODUCTION For two centuries after the discovery of America, Texas remained an unexplored and almost unvisited frontier province of Spain's far-flung empire. The reasons for this are not far to seek. First of all, Texas was almost inaccessible from the Spanish point of view. There were three possible ways of getting to it, each one less attractive than the pre- ceding. The one by sea was over the totally un- charted Gulf of Mexico, which was rendered doubly difficult by the peculiar formation of Matagorda Peninsula and the bay it protects. -

Texas Indians CH 4 TEXAS HISTORY First Texans

Texas Indians CH 4 TEXAS HISTORY First Texans Native Americans adapted to and used their environment to meet their needs. Plains Indians People who move from place to place with the seasons are nomads. The main advantage of teepees was their mobility. Plains Indians The Apaches were able to attack both the Spanish and other Indian groups because of their skilled use of horses. Apaches used their skill at riding horses to assert dominance. Plains Indians The Comanche became wealthy as skilled buffalo hunters. Hunters used buffalo hides for clothing and shelter and ate the meat. All Plains Indians lived off the buffalo. Plains Indians The Comanche first entered Texas from the Great Plains. The Comanche later drove the Apache into the Mountains and Basins region of West Texas and into New Mexico. Plains Indians The Lipan and Mescalero were subgroups of the Apaches. Southeastern Indians The Caddos were a matrilineal society, which meant they traced their families through the mother’s side. Caddos farmed and practiced crop rotation to prevent the soil from wearing out. Southeastern Indians Farming changed Native American culture by creating more complex, permanent societies. Western Gulf Indians Gulf Coast Indians were different from Plains Indians because they were able to eat seafood from the Gulf, including oysters, clams, turtles and fish. Western Gulf Indians The Karankawa and Coahuiltecan were both were nomads along the Gulf Coast. They didn’t farm because they lived in a dry area. Pueblo Indians The Pueblo were from the Mountains and Basins region and built adobe homes of mud and straw. -

Minor League Baseball Report

PRELIMINARY DRAFT – SUBJECT TO REVISION CONFIDENTIAL CITY OF SAN ANTONIO MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL DUE DILIGENCE REPORT PREPARED BY: BARRETT SPORTS GROUP, LLC SEPTEMBER 16, 2016 The following report has been prepared for the internal use of the City of San Antonio and is subject to the attached limiting conditions and assumptions The scope of services has been limited – additional due diligence required Findings are preliminary in nature and subject to revision This report may not be used, in whole or in part, in any financing document Preliminary Draft – Subject to Revision Page 2 Confidential TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY II. SAN ANTONIO MISSIONS OVERVIEW III. TRIPLE-A BASEBALL OVERVIEW IV. MARKET OVERVIEW V. PRELIMINARY PROGRAM RECOMMENDATION VI. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS VII. FINANCING ALTERNATIVES APPENDIX A: MARKET DEMOGRAPHICS APPENDIX B: BRAILSFORD & DUNLAVEY REPORT REVIEW APPENDIX C: MLB POTENTIAL LIMITING CONDITIONS AND ASSUMPTIONS Preliminary Draft – Subject to Revision Page 3 Confidential I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Barrett Sports Group, LLC (BSG) is pleased to present our preliminary findings to the City of San Antonio (City) The City retained BSG to evaluate potential feasibility of the proposed development of a new state-of- the-art Triple-A minor league baseball stadium in San Antonio, Texas Seven potential Triple-A stadium sites have been identified by the City and Populous . ITC . Fox Tech South . Fox Tech . UTSA . Alamodome . Irish Flats . Fox Tech North The City is currently home to the Double-A San Antonio Missions The findings are limited since BSG has not completed market surveys and/or focus group sessions – consideration could be given to completing these tasks Preliminary Draft – Subject to Revision Page 5 Confidential I. -

Texas Indians Fishermen

Texas Indians Fishermen Nomads Karankawa • Tall • Strong • Canes in their nose • Lived near coast in winter/moved inland during the summer • Friendly unless provoked Atakapans • Short • Stocky • Bushy Hair • Lived near the ocean in the summer/moved inland during the winter Fisherman • Shelter • Wikiups • Lean-To’s • Brush Shelter Fishermen • Ate seafood, seeds, nuts—even locusts if hungry. • Used Alligator fat for bug repellant • Used canoes for moving and fishing • Shaped babies’ heads to cone shape Plant Gatherers Nomads Coahuiltecans • There was no one tribe called the Coahuiltecans. There were many bands that lived in the Coahuiltecan region. • Up to 7 different languages. There were up to 140 different “tribal” names. • Small, strong wore bones/teeth for decoration • Food became scarce as Spanish moved in. Ate pecans, acorns, mesquite beans, small animals. • Used dirt as a medicine for stomach aches. Tonkawa • Very friendly • Got along with most other tribes • Thought they descended from wolves—would not eat them. • Ate very well. Many plants and animals in their region. Plant Gatherers • Most severe punishment--threw water on their kids heads • Named kids when 2-3 years old • Wikiups and Brush Shelters Farmers Caddo/Wichita • pierced nose/tattos • baskets • pottery • 2-year corn supply saved • most advanced Caddo Shelter Wichita Shelter Jumano • pottery • welcome house • neat • clean • short hair • turquoise jewelry Jumano Shelter/Pueblos Farmers • They ate corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, and trapped animals. • They also traded frequently with other kinds of natives. Hunters Nomads Kiowa • Hunters • Lived in Tepees • Called horses—sacred dogs Kiowa • Famous for their beadwork Apache • There were two groups living in Texas—the Mescalero and Lipan Apache • They were not friendly to each other.