CHAPTER-I the Dimasas: the Land and People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Ecotourism in Assam: a Promising Opportunity for Development

SAJTH, January 2012, Vol. 5, No. 1 Ecotourism in Assam: A Promising Opportunity for Development MEENA KUMARI DEVI* *Meena Kumari Devi, Associate Professor, Economics, S.D College, Hajo, Assam. INDIA Introduction Ecotourism is a new form of tourism based on the idea of sustainability. The term “ecotourism” has diverse meanings and scholars are not unanimous on what ecotourism really means. The concept of ecotourism came into prominence in the late 80s as a strategy for reconciling conservation with development in ecologically rich areas. Conservation of natural resources prevents environmental degradation. That is why, this form of tourism has received global importance. It is currently recognized as the fastest growing segment of the tourism market (Yadav 2002). The World Ecotourism Summit, held in Quebee City, Canada, from 19 th to 22 nd May, 2002, declared the year 2002 as the International Year of Ecotourism. Such declarations highlight the relevance and recognition of ecotourism, both locally and globally. Presently, ecotourism comprises 15-20% of international tourism. The growth rate of ecotourism and nature based activities is higher than most of the other tourism segments (Kandari and Chandra, 2004). Its market is now growing at an annual rate of 30% (Whelan, 1991). From this, the significance of ecotourism can be very easily evaluated. Definitions of Ecotourism: The concept of ecotourism is relatively new and often confusing. Therefore, a range of definitions of ecotourism has evolved. The term ‘ecotourism’ was coined by Hector Ceballos Lascurian in 1983 to describe nature based travel. Ceballos Lascurisn (1987) defines it as “traveling to relatively undisturbed or un contaminated natural areas with specific © South Asian Journal of Tourism and Heritage 180 MEENA KUMARI DEVI objectives of studying , admiring, enjoying the scenery and its wild plants and animals, as well as existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas”. -

Kikon Difficult Loves CUP 2017.Pdf

NortheastIndia Can we keep thinking of Northeast India as a site of violence or of the exotic Other? NortheastIndia: A PlacerfRelations turns this narrative on its head, focusing on encounters and experiences between people and cultures, the human and the non-human world,allowing forbuilding of new relationships of friendship and amity.The twelve essaysin this volumeexplore the possibilityof a new search enabling a 'discovery' of the lived and the loved world of Northeast India fromwithin. The essays in the volume employa variety of perspectives and methodological approaches - literary, historical, anthropological, interpretative politics, and an analytical study of contemporary issues, engaging the people, cultures, and histories in the Northeast with a new outlook. In the study, theregion emerges as a place of new happenings in which there is the possibility of continuous expansionof the horizon of history and issues of currentrelevance facilitating newvoices and narratives that circulate and create bonding in the borderland of South, East and SoutheastAsia. The book willbe influentialin building scholarship on the lived experiences of the people of the Northeast, which, in turn, promises potentialities of connections, community, and peace in the region. Yasmin Saikiais Hardt-Nickachos Chair in Peace Studies and Professor of History at Arizona State University. Amit R. Baishyais Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the University of Oklahoma. Northeast India A Place of Relations Editedby Yasmin Saikia Amit R. Baishya 11�1 CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One LibertyPlaza, 20th Floor, New York,NY 10006, USA 477 WilliamstownRoad, Port Melbourne, vie 3207, Australia 4843/24, 2nd Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, Delhi-110002, India 79 Anson Road,#06-04/06, Singapore 079906 Contents Cambridge UniversityPress is part of theUniversity of Cambridge. -

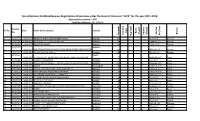

Fee Collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies Under The

Fee collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies under the Head of Accounts "1475" for the year 2017-2018 Applications recieved = 1837 Total fee collected = Rs. 2,20,541 Receipt Sl. No. Date Name of the Society District No. Copy Name Name Branch Change Change Challan Address Renewal Certified No./Date Duplicate 1 02410237 01-04-2017 NABAJYOTI RURAL DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta 200 640/3-3-17 Barpeta 2 02410238 01-04-2017 MISSION TO THE HEARTS OF MILLION Barpeta 130 10894/28-3-17 Barpeta 3 02410239 01-04-2017 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Barpeta 200 2935/9-3-17 Barpeta 02410240 Barpeta 4 01-04-2017 SIPNI SOCIO ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION 100 5856/15-2-17 Barpeta 5 02410241 01-04-2017 DESTINY WELFARE SOCIETY Barpeta 100 5857/15-2-17 Barpeta 08410259 Dhubri 6 01-04-2017 DHUBRI DISTRICT ENGINE BOAT (BAD BADHI) OWNER ASSOCIATION 75 14616/29-3-17 Dispur 7 15411288 03-04-2017 SOCIETY FOR CREATURE KAM(M) 52 40/3-4-17 Dispur 8 15411289 03-04-2017 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DAKHIN GUWAHATI JATIYA BIDYALAYA KAM(M) 125 15032/30-2-17 Dispur 9 24410084 03-04-2017 UNNATI SIVASAGAR 100 11384/15-3-17 Dispur 10 27410050 03-04-2017 AMGULI GAON MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11836/16-2-17 Dispur 11 27410051 03-04-2017 MANPUR MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11837/15-2-17 Dispur 12 27410052 03-04-2017 ULUBARI MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11835/16-2-17 Dispur 13 15411291 04-04-2017 ST. CLARE CONVENT EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY KAM(M) 100 342/5-4-17 Dispur 14 16410228 04-04-2017 SERAPHINA SEVA SAMAJ KAM(R) 60 343/5-4-17 Dispur 15 16410234 -

Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road

No.24-5/2017-N.M.(Assam) Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11th Floor, Pt. Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-3 Dated : 3v March, 2017 To The Pay and Accounts Officer Ministry of Minority Affairs, 11th Floor, Pt. Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003 Subject: Sanction of Project under Nai Manzil Scheme in the State of Assam to be implemented by Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam-782435 - Release of 1st installment (30%) of training cost for additional 120 trainees during 2016-17 Sir, In continuation of this Ministry's Sanction Order of even number dated 24.03.2017, I am directed to convey the approval of the President of India to sanction additional 120 Nos. of trainees under the Nai Manzil Project to Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil All Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam -782435 for the Assam State. The total number of trainees has been enhanced to 970 Nos. from 850 Nos. with this additional allocation. Consequently, the cost of the Project has also been enhanced to Rs. 5,48,05,000/- from Rs. 4,80,25,000/-. This cost ceiling is subject to common norms of Ministry of Skill Development & Entrepreneurship for skill component applicable from time to time. 2. I am also directed to convey the sanction of the President of India for release of Rs. 20,34,000/- ( Rupees twenty lakh and thirty four thousand only) (making total release to Rs. 1,64,41,500/-) for 970 trainees as 1st installment (30%) of Grants-in-aid to 111 Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam -782435 during 2016-17. -

GOVT. of ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai

GOVT. OF ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai No: DZP/142/2008-09/ Dated- 24/06/2013 To, The Finance (Economic Affair) Assam, Dispur, Ghy-06 Sub- Regarding Information PRI List Reference No- FEA (SFC) 81/2013/5/ Dated-04-06-2013 Sir, With reference to the subject cited above, I have the honour to furnish detailed Names of President of Zilla Parishad. Anchalik Panchayat & Gaon Panchayat along with Soft & Hard Copies. This is for favour of your kind information & necessary action. You’re faithfully Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai Memo No: - DZP/142/2008-091 Dated- 24/06/2013 Copy for favour of kind information to:- 1. The Commissioner Panchayat & Rural Development. 2. The Deputy Commissioner Darrang, Mangaldai 3. The President Darrang Zilla Parishad, Mangaldai Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai GOVT. OF ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai 1. Name of ZP President:- Mrs. Mohsina Khatun 2. Name AP President 1. Pub Mangaldai:-Md. Jainal Abedin 2. Sipajhar:-Ayub Ancharai 3. Dalgaon :-Raihana Sultana Ahmed 4. Pachim Mangaldai:-Priti Rekha Baruah 5. Bechimari:-Firuja Khatun Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai List of GP President SI No Name & No. of ZPC Name & No. of Name & No. of GP Name of winning AP candidate 1 6.Tengabari Ms. Padmeswari No. 1 Deka 2 Lakhimpur/Tengabari 7.Lakhimpur Mr. Lohit Ch. Sarma 3 ZPC 8.Namkhola Ms. Babita Kalita Saikia 4 No. 1 Kalaigaon 9.Buragarh Mr. Hari Ram Barua 5 AP 10.Outala Mr. Kamini Kakati Saikia 6 1.Rajapukhuri Mr. -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings. -

Final Shortlisted Hospital Administrator

Provisionally shortlisted candidates for Interview for the Post of Hospital Administrator under NHM, Assam Instruction: Candidates shall bring all relevant testimonials and experience certificates in original to produce before selection committee along with a set of self attested photo copies for submission at the time of interview. Shortlisting of candidates have been done based on the information provided by the candidates and candidature is subject to verification of documents at the time of interview. Date of Interview : 23/10/2018 Time of Interview : 11:00 AM (Reporting Time - 10:00 AM) Venue : Office of the Mission Director, NHM, Assam, Saikia Commercial Complex, Christianbasti, Guwahati-5 Sl Regd. ID Candidate Name Father Name Address No. PARTHAJIT C/o-HARANIDHI CHAKRABORTY, H.No.-27, Vill/Town- NHM/HPTLA/0 ABHISHEK 1 BHATTACHARY ARJYAPATTY NEAR DURGA BARI, P.O.-SILCHAR, P.S.- 016 BHATTACHARYA A SILCHAR, Dist.-Cachar, State-ASSAM, Pin-788001 C/o-Amit Rajpal, H.No.-1-GHA-18, Mnumarg, Al;war, NHM/HPTLA/0 Dr. Arjun Singh 2 Amit Rajpal Vill/Town-Alwar, P.O.-HPO, Alwar, P.S.-Kotwali, Alwar, 005 Rajpal Dist.-Alwar, State-Rajasthan, Pin-301001 C/o-DR. MUNINDRA MALAKAR, H.No.-56, Vill/Town-DR. NHM/HPTLA/0 NIMAICHAND ZAKIR HUSSAIN PATH, NEAR DOWN TOWN 3 ARYA THOUDAM 017 THOUDAM HOSPITAL., P.O.-DISPUR, P.S.-DISPUR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781006 C/o-TIRTHA KONWAR, H.No.-Rangoli bam path, Vill/Town- NHM/HPTLA/0 BHASKAR JYOTI TIRTHA 4 SIVASAGAR, P.O.-SIMALUGURI, P.S.-SIMALUGURI, 012 KONWAR KONWAR Dist.-Sivasagar, State-ASSAM, -

Dimasa Kachari of Assam

ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY NO·7II , I \ I , CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I MONOGRAPH SERIES PART V-B DIMASA KACHARI OF ASSAM , I' Investigation and Draft : Dr. p. D. Sharma Guidance : A. M. Kurup Editing : Dr. B. K. Roy Burman Deputy Registrar General, India OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS FOREWORD v PREFACE vii-viii I. Origin and History 1-3 II. Distribution and Population Trend 4 III. Physical Characteristics 5-6 IV. Family, Clan, Kinship and Other Analogous Divisions 7-8 V. Dwelling, Dress, Food, Ornaments and Other Material Objects distinctive qfthe Community 9-II VI. Environmental Sanitation, Hygienic Habits, Disease and Treatment 1~ VII. Language and Literacy 13 VIII. Economic Life 14-16 IX. Life Cycle 17-20 X. Religion . • 21-22 XI. Leisure, Recreation and Child Play 23 XII. Relation among different segments of the community 24 XIII. Inter-Community Relationship . 2S XIV Structure of Soci141 Control. Prestige and Leadership " 26 XV. Social Reform and Welfare 27 Bibliography 28 Appendix 29-30 Annexure 31-34 FOREWORD : fhe Constitution lays down that "the State shall promote with special care the- educational and economic hterest of the weaker sections of the people and in particular of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist States in fulfilling their responsibility in this regard, the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the President under the Constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include in or exclude from the lists, any caste or tribe. -

Notice Regarding the Post of Para Legal Volounteer Under District

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY :: HOJAI;| SA KARDEV NAGAR (ASSAM) ]UDICIAI Cq'RT CAMRJS, SCNIGRDEV IIIAGAR, HOJAI (ASSAM), wN-74242 PHONE : 9707208575 E-MAIL ID : dlsahoiai@qmail,com I{OTICE Applications are invited from the local residents jn standard form along with two number of passport size photographs, for selection of around 70 numbers of pLV,s who are willing to serve as Para Legal Volunteer at Hoiai district under District Legal Services Authority, Hojai, Sankardev Nagar. The applicants should have the following qualifications to apply for the selection of Para Legal Volunteers- 1. He/ She must be a citizen of India and should be from any one of the follor\ring groups - ' Teachers (including retired teacheE) ' Retired Government servants and senior Gtizens. ' Master of Social Work Students and Teachers. ' Anganwadi Worlcrs. ' Doctors/ Ph)6icians. ' Students & Law Students (till they enroll as lawyers) ' Members of non- political, service oriented N@s and Clubs. ' Members of Women Neighborhood Groups, Maithri Sanghams and other Self Help Groups including Marginalized/ Vulnenble groups. 2. The applicants should pass minimum matriculatjon with a capacity for over all comprehension and should have mind set to assist the needy in society coupled with compassion, emEtthy and corrcern fior the uplifonent of marginalized and weaker sections of the society. They must have the unflindting commitment towards the cause which should be translated into the work they undertake. 3. Preferably the PLVS shall be selected, who do not look up to the income they derive from their services as PLVS, but they should have a mind set to assist the needy in the society. -

District-Wise Number of Present Incumbents of Home Guards Name of Name of Name of the Home Gender Male/ Sl

District-wise number of present Incumbents of Home Guards Name of Name of Name of the Home Gender Male/ Sl. No. Father's Name Date of Birth Remarks if any the State the Dist. Guards Female [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] 5544 Assam Sivasagar Hema Gogoi Lt.Tankeswar Gogoi 20-10-1976 Male 5545 Assam Sivasagar Bikash Nath Khogeswar Nath 01-02-1976 Male 5546 Assam Sivasagar Jatin Baruah Prabhat Baruah 01-10-1983 Male 5547 Assam Sivasagar Bhupen Baruah Noreswar Baruah 15-03-1976 Male 5548 Assam Sivasagar Horen Gogoi Lt.Mohan Gogoi 30-12-1981 Male 5549 Assam Sivasagar Ananta Saikia Lt.Jugen Saikia 26-05-1970 Male 5550 Assam Sivasagar Ranjit Phukan Lt.Mohendra Phukan 01-11-1976 Male 5551 Assam Sivasagar Horen gogoi Lt.Jiten Gogoi 01-05-1981 Male 5552 Assam Sivasagar Ananda Dutta Minik Dutta 01-03-1987 Male 5553 Assam Sivasagar Bijit Chutia Ganesh Chutia 01-01-1984 Male 5554 Assam Sivasagar Naba Jyoti Nath Radhika Nath 30-09-1982 Male 5555 Assam Sivasagar Krishna Das Belat Das 31-12-1979 Male 5556 Assam Sivasagar Pranab Nath Dimbeswar Nath 30-10-1982 Male 5557 Assam Sivasagar Horen Borah Lt.Sonai Borah 01-10-1976 Male 5558 Assam Sivasagar Ramen Bhuyan Lt.Jugai Bhuyan 01-10-1985 Male 5559 Assam Sivasagar Durlav Saikia Biren Saikia 28-10-1989 Male 5560 Assam Sivasagar Prabhat Dutta Lt.Jatiram Dutta 01-03-1974 Male 5561 Assam Sivasagar Nitu Borah Thankeswar Borah 30-11-1983 Male 5562 Assam Sivasagar Bidyut Bikash Nath Prmod Ch Nath 30-06-1986 Male 5563 Assam Sivasagar Robin Das Pradip Das 05-03-1983 Male 5564 Assam Sivasagar Monoj Gogoi Lt. -

Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution in Three Tribal Societies of North East India

NESRC Peace Studies Series–4 Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution in Three Tribal Societies of North East India Editor Alphonsus D’Souza North Eastern Social Research Centre Guwahati 2011 Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Alphonsus D’Souza / 1 Traditional Methods of Conflict Management among the Dimasa Padmini Langthasa / 5 The Karbi Community and Conflicts Sunil Terang Dili / 32 Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution Adopted by the Lotha Naga Tribe Blank Yanlumo Ezung / 64 2 TRADITIONAL METHODS OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION INTRODUCTION 3 system rather than an adversarial and punitive system. inter-tribal conflicts were resolved through In a criminal case, the goal is to heal and restore the negotiations and compromises so that peaceful victim’s well-being, and to help the offender to save relations could be restored. face and to regain dignity. In a civil case, the parties In the case of internal conflicts, all the three involved are helped to solve the dispute in a way communities adopted very similar, if not identical, that there are no losers, but all are winners. The mechanisms, methods and procedures. The elders ultimate aim is to restore personal and communal played a leading role. The parties involved were given harmony. ample opportunities to express their grievances and The three essays presented here deal with the to present their case. Witnesses were examined and traditional methods of conflict resolution practised cross examined. In extreme cases when evidence was in three tribal communities in the Northeast. These not very clear, supernatural powers were invoked communities have many features in common. All the through oaths. The final verdict was given by the elders three communities have their traditional habitat, in such a way that the guilty were punished, injustices distinctive social organisation and culture.