Kikon Difficult Loves CUP 2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur's Ahoms

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur’s Ahoms - An Ethnographic Approach Barnali Chetia, PhD, Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Vadodara, India. Department of Linguistics Abstract- Mong Dun Shun Kham, which in Assamese means xunor-xophura (casket of gold), was the name given to the Ahom kingdom by its people, the Ahoms. The advent of the Ahoms in Assam was an event of great significance for Indian history. They were an offshoot of the great Tai (Thai) or Shan race, which spreads from the eastward borders of Assam to the extreme interiors of China. Slowly they brought the whole valley under their rule. Even the Mughals were defeated and their ambitions of eastward extensions were nipped in the bud. Rangpur, currently known as Sivasagar, was that capital of the Ahom Kingdom which witnessed the most glorious period of its regime. Rangpur or present day sivasagar has many remnants from Ahom Kingdom, which ruled the state closely for six centuries. An ethnographic approach has been attempted to trace the history of indigenous culture and traditions of Rangpur's Ahoms through its remnants in the form of language, rites and rituals, religion, archaeology, and sacred sagas. Key Words- Rangpur, Ahoms, Culture, Traditions, Ethnography, Language, Indigenous I. Introduction “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.” -P.B Shelley Rangpur or present day Sivasagar was one of the most prominent capitals of the Ahom Kingdom. -

View, Satram, with the Secret Approval of Chandrakanta Hatched a Conspiracy to Murder Purnananda Buragohain.But the Plot Was Discovered

British Occupation of Assam Unit 5 UNIT 5: BRITISH OCCUPATION OF ASSAM UNIT STRUCTURE 5.1 Learning Objectives 5.2 Introduction 5.3 Anglo-Burmese Wars 5.4 Treaty of Yandaboo and British Conquest of Assam 5.5 Let Us Sum Up 5.6 Further Reading 5.7 Answers to Check Your Progress 5.8 Model Questions 5.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to: l Discuss the Burmese invasion of Assam, l Describe the circumstances leading to British intervention in Assam and the Anglo-Burmese wars, l Explain the terms of the Treaty of Yandaboo and the significance of this historic treaty in the history of Assam, 5.2 INTRODUCTION This unit begins with a brief background of the Burmese invasion of Assam. We are going to discuss the factors that led to foreign intervention in Assam. We will also discuss in detail the circumstances leading to the British intervention in Assam as a result of the latter’s fight against the Burmese. A brief account of the course of the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824) has also been discussed as well as the terms of the Treaty of Yandaboo that brought about an end to the war. The significance and the consequent changes that occurred in the political history of Assam after the Treaty of Yandaboo have been dealt with in detail. History of Assam from the 17th Century till 1947 C.E. 61 Unit 5 British Occupation of Assam 5.3 ANGLO-BURMESE WARS Prior to the intervention of the British East India Company, Assam was ruled by the Ahom dynasty. -

NAGALAND Basic Facts

NAGALAND Basic Facts Nagaland-t2\ Basic Facts _ry20t8 CONTENTS GENERAT INFORMATION: 1. Nagaland Profile 6-7 2. Distribution of Population, Sex Ratio, Density, Literacy Rate 8 3. Altitudes of important towns/peaks 8-9 4. lmportant festivals and time of celebrations 9 5. Governors of Nagaland 10 5. Chief Ministers of Nagaland 10-11 7. Chief Secretaries of Nagaland II-12 8. General Election/President's Rule 12-13 9. AdministrativeHeadquartersinNagaland 13-18 10. f mportant routes with distance 18-24 DEPARTMENTS: 1. Agriculture 25-32 2. Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services 32-35 3. Art & Culture 35-38 4. Border Afrairs 39-40 5. Cooperation 40-45 6. Department of Under Developed Areas (DUDA) 45-48 7. Economics & Statistics 49-52 8. Electricallnspectorate 52-53 9. Employment, Skill Development & Entrepren€urship 53-59 10. Environment, Forests & Climate Change 59-57 11. Evalua6on 67 t2. Excise & Prohibition 67-70 13. Finance 70-75 a. Taxes b, Treasuries & Accounts c. Nagaland State Lotteries 3 14. Fisheries 75-79 15. Food & Civil Supplies 79-81 16. Geology & Mining 81-85 17. Health & Family Welfare 85-98 18. Higher & Technical Education 98-106 19. Home 106-117 a, Departments under Commissioner, Nagaland. - District Administration - Village Guards Organisation - Civil Administration Works Division (CAWO) b. Civil Defence & Home Guards c. Fire & Emergency Services c. Nagaland State Disaster Management Authority d. Nagaland State Guest Houses. e. Narcotics f. Police g. Printing & Stationery h. Prisons i. Relief & Rehabilitation j. Sainik Welfare & Resettlement 20. Horticulture tl7-120 21. lndustries & Commerce 120-125 22. lnformation & Public Relations 125-127 23. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : NAGALAND DISTRICT : Dimapur Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 STATE CATTLE BREEDING FARM MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, 1965 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 STATE CHICK REPARING CENTRE MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, TEL 1965 10 - 50 NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 3610-Manufacture of furniture 3 MS MACHANIDED WOODEN FURNITURE DELAI ROAD NEW INDUSTRIAL ESTATE DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD 1998 10 - 50 UNIT CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 4 FURNITURE HOUSE LEMSENBA AO VILLAGE KASHIRAM AO SECTOR DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: 2002 10 - 50 NA , TEL NO: 332936, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5220-Retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialized stores 5 VEGETABLE SHED PIPHEMA STATION DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA 10 - 50 NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5239-Other retail sale in specialized stores 6 NAGALAND PLASTIC PRODUCT INDUSTRIAL ESTATE OLD COMPLEX DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , 1983 10 - 50 TEL NO: 226195, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

A Study on Assamese Traditional Ornaments of Barpeta District of Assam Deepa Karmakar M.Com 4Th Semester, B

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-III, Issue-V, March 2017, Page No. 109-119 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com A Study on Assamese Traditional Ornaments of Barpeta District of Assam Deepa Karmakar M.Com 4th Semester, B. H. College, Howly, Assam, India Dr. Bhabananda Deb Nath Assistant Professor, Dept. of Accountancy, B. H. College, Howly, Assam, India Abstract Assamese Ornaments are one of the most important parts of Assamese Culture. It is generally made by Gold, Silver and Gold-Plated. Assamese Ornaments were originally used by Ahom Kings and Queens of Assam and from that period these Ornaments have occupied an honorable position in Assamese Society. ‘Gold Washing’ and ‘Manufacturing of Ornaments’ were two important ancient Industries of Assam. Assamese Traditional Ornaments (ATOs) are typically hand-made, and the design mostly depicts the Floral and Faunal treasures of the region. Barpeta District of Assam is recognized as one of the most important hub of manufacturing Assamese Ornaments. Therefore, the present study shows the History of ATOs, Manufacturing and Marketing of ATOs and the importance of ATOs as a Cultural Resource of Assamese people. Finally, the problem with sustainability of ATOs compared with the Branded Jewellery has become a big challenge as noticed during the study. The study is based on both Primary and Secondary data and have come to the conclusion that ATOs has good market potentiality for its unique design, shape, size and look. -

Sub-Coal Imaging of Lakwa-Sonari Field, A&AA Basin, Using Local

Sub-Coal Imaging of Lakwa-Sonari Field, A&AA Basin, using Local Angle Domain Wavefield Decomposition Saheb Ghosh*, V P Singh, KS Negi Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited [email protected] Keywords Sub-Coal Imaging, Constrained Dix Inversion, Full Azimuth Reflection Tomography, Local Angle Domain Imaging, Specular and Diffraction Imaging Summary The area under study, Lakwa-Sonari field, falls in UAN, Assam & Assam-Arakan Basin, a Tertiary onland Sub-coal imaging is one of major exploration objectives in basin in the north-eastern part of India and the data used in Lakwa-Sonari field. Apart from coal, Sonari field has a high the study is a 3D onland data of area 400 Sq Km with a bin velocity zone above coal that causes structural distortion of size of 25x25m. The area is both structurally and sub-coal sequences. High impedance contrast of Barail coal stratigraphically complex due to presence of Barail coal, causes a low illumination of underneath source rock and complex fault networks and proximity to thrusts. In Lakwa Lower Barail Sands (LBS). So, successful sub-coal imaging below Barail Coal Shale (BCS), Kopili acts as a main source demands a reliable estimation of interval velocity model rock and the Lower Barail Sands (LBS) are potential from poorly illuminated reflection signal and a migration hydrocarbon reserves. Apart from the LBS sands, Sonari algorithm to reduce coal generated wavefield distortion. In field has a high velocity anomaly above coal that causes this work formation dependent constraint dix inversion and structural distortion from Tipam sand to basement. So, full azimuth reflection tomography is used for initial enhancing reflector continuity and imaging of pre-barail modelling and refinement of depth interval velocity. -

GOVT. of ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai

GOVT. OF ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai No: DZP/142/2008-09/ Dated- 24/06/2013 To, The Finance (Economic Affair) Assam, Dispur, Ghy-06 Sub- Regarding Information PRI List Reference No- FEA (SFC) 81/2013/5/ Dated-04-06-2013 Sir, With reference to the subject cited above, I have the honour to furnish detailed Names of President of Zilla Parishad. Anchalik Panchayat & Gaon Panchayat along with Soft & Hard Copies. This is for favour of your kind information & necessary action. You’re faithfully Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai Memo No: - DZP/142/2008-091 Dated- 24/06/2013 Copy for favour of kind information to:- 1. The Commissioner Panchayat & Rural Development. 2. The Deputy Commissioner Darrang, Mangaldai 3. The President Darrang Zilla Parishad, Mangaldai Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai GOVT. OF ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai 1. Name of ZP President:- Mrs. Mohsina Khatun 2. Name AP President 1. Pub Mangaldai:-Md. Jainal Abedin 2. Sipajhar:-Ayub Ancharai 3. Dalgaon :-Raihana Sultana Ahmed 4. Pachim Mangaldai:-Priti Rekha Baruah 5. Bechimari:-Firuja Khatun Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai List of GP President SI No Name & No. of ZPC Name & No. of Name & No. of GP Name of winning AP candidate 1 6.Tengabari Ms. Padmeswari No. 1 Deka 2 Lakhimpur/Tengabari 7.Lakhimpur Mr. Lohit Ch. Sarma 3 ZPC 8.Namkhola Ms. Babita Kalita Saikia 4 No. 1 Kalaigaon 9.Buragarh Mr. Hari Ram Barua 5 AP 10.Outala Mr. Kamini Kakati Saikia 6 1.Rajapukhuri Mr. -

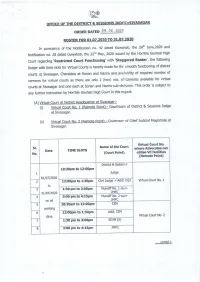

Courtroom of District & Sessions Judge at Sivasagar

rtr OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE:TSMSAGAR ORDERDAIED 2.!3:P ROSTER FOR 01.07.2020 TO 31'07'2020 In pu6uance of the Notification no' 42 dated Guwahati, the 25h June,2020 and Gauhati High Notification no. 28 dated Guwahati, th e 22rt MaY , 2020 issued by the Hon'ble the following Court regarding 'Restricted Court Functioning' with 'staggered Roste/, gmooth functioning of district Roster with time slots for virtual c-ourts is hereby made for thf number of courts at Sivasagar, Charaideo at Sonari and Nazira and avalralllity of required virtual cameras for virtual courts as there are only 2 (two) nos oi tatetas available for is subiect to courts at Sivasagar and one each at Sonari and Nazira sub{ivisions This order any further instruction by Hon'ble Gauhati l-ligh Oourt in this r€gard (A) ViItual Court at Distrid Headouarter at Sivasaoarl tO Vrtualgouilo-j-tleoggtq0!}:courtroom of District & Sessions Judge at Sivasagar. (iD Virtual Couft No, 2 (Remote Point):- Courtroor of ChiefJudicial Magistrate at Sivasagar. Virtual Court No. sl. Name of the Court where Advocates can Date TIME SLOTS No. (Court Point) utilise VC facilitiee (Remote Point) District & sessiorls 10r30am to 12:00Pm 1 Judge 01107/2020 Virtual Court No. 1 2 12:00pm to 1:30pm Civil Judge + Add!. D3l to 3 1:30 pm to 3:O0Pm I'"lunsiff No. l_oJh- 3110712020 JMFC 4 3:0o pm to 4r15pm Mungff No. 2-cum_ on all JT4FC 5 loi3oam to 12:00Pm clM working 6 12:00pm to 1:30Pm Addt. cJ14 days. -

Nagaland State Disaster Management Plan

CONTENTS CHAPTER I 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1-3 CHAPTER –II 2. OVERVIEW OF THE STATE 4-21 2.1.1 Location 2.2 Socio – economic Division 2.3 Administrative Divisions. 2.4 Physiographic of Nagaland. 2.5 Geology of Nagaland. 2.6 Climate and Rainfall. 2.7 Drainage. 2.8 Demographic Profile & Literacy. 2.9 Demographic Profile of Nagaland. 2.10 State Education. 2.11 Health. 2.12 Forest. 2.13 Agriculture and Land Use Pattern. 2.14 Soils of Nagaland. 2.15 Industry. 2.16 Oil & Minerals. 2.17 Transportation. 2.18 Power. 2.19 Water Supply. 2.20 State Domestic Product. CHAPTER III 3. HAZARD VUNERABILTY ANALYSIS OF THE STATE 22-74 OF NAGALAND. 3.1 Earthquake 3.1.1 Risk and Vulnerability Analysis. 3.1.2 Measures to be taken before, during and after an Earthquake. 3.2 Landslides 3.2.1 Hazard analysis. 3.2.2 Landslide Indicators. 3.2.3 Prevention and Mitigation Measures. 3.2.4 Structural Measures. (i) Retaining wall, Embankments and Dams. (ii) Bamboo/wooden Nail Reinforcements. (iii) Water Control Methods. (iv) Surface Water. (v) Catch-water drain. (vi) Cross drain. (vii) Subsurface water. (viii) Deep trench drain. (ix) Topographic Treatment. 3.2.5. Biological Measures 3.2.6. Non-Structural Measures 3.2.7. Remote Sensing & GIS in Landslide Management 3.2.8. Generating Awareness 3.2.9. Recommendation 3.3. District wise Vulnerability Assessment 3.3.1. Dimapur 3.3.1.2. Vulnerability Analysis 3.3.2. Kiphire 3.3.2.1. Vulnerability Analysis 3.3.3. Kohima 3.3.3.1. -

International Journal of History & Scientific Approach

International Journal of History & Scientific Approach History and Culture: A Study on the Importance of the Place Names of Chandrapur Rosie Patangia Assistant Professor and Head, Deptt of English, Narangi Anchalik Mahavidyalaya, Narengi, Guwahati-171, Dist: Kamrup (Metro), Assam, India & Ph.D Research Scholar, Folklore Department, Gauhati University, Guwahati- 781014, Assam, India Abstract: History has its culture. Every place is denoted by a name. Each place name carries its own culture and tradition. The memory of a place is deeply embedded in its history, historical characters, legendary heroes, historical events etc. Assam in general and Kamrup in particular is rich in its culture and history. The place names speak of the past history of that place and helps in building identity. In Assam, we find innumerable places connected with oral narratives, folk beliefs, culture, history, myths, and legends. The present paper is an attempt to study the place names of Chandrapur and its cultural and historical significance. Key words: History, Culture, Place, Names, Chandrapur, historical significant. Introduction Every place from the macrocosm to the microcosm embodies its community, history and culture. Robert Murphy (1986) highlights that “Culture means the total body of tradition borne by a society and transmitted from generation to generation.” The Oxford English Dictionary (2007) defines a ‘place’ as a ‘particular position or area or a portion of space occupied by or set aside for someone or something’. It defines a ‘name’ as ‘a word or words by which someone or something is known.”Each place has its own cultural and historical background. While the term ‘cultural’ refers to the ideas, customs and social behavior of a society, the word ‘historical’ relates to past events or history. -

1. the Ahom Dynasty Ruled the Ahom Kingdom for Approximately A) 300 Years B) 600 Years C) 500 Years D) 400 Years

Visit www.AssamGovJob.in for more GK and MCQs 1. The Ahom Dynasty ruled the Ahom Kingdom for approximately a) 300 Years b) 600 Years c) 500 Years d) 400 Years 2. Who was the founder of the Varmana Dynasty? (a) Bhaskar Varman (b) Pushyavarman (c) Mahendravarman (d) Banabhatta 3. In which year did the Koch King Naranarayan invade the Ahom kingdom? (a) 1555 (b) 1562 (c) 1665 (d) 1552 4. The Yandaboo Treaty was signed in 1826 between (a) British Crown and the Burmese (b) British King and the Ahom King (c) East India Company and the Ahom King (d) East India Company and the Burmese 5. Which Ahom king was known as ‘Dihingia Roja’ ? (a) Suhungmung (b) Sukapha (c) Suseupa (d) Sudangpha 6. Who was the last ruler of Ahom kingdom? (a) Sudingpha (b) Jaydwaja Singha (c) Jogeswar Singha (d) Purandar Singha 7. The Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang visited Kamarupa in which year? (a) 602 A.D. (b) 643 A.D. (c) 543 A.D. (d) 650 A.D. 8. Which among the following has written the Prahlada Charita? (a) Rudra Kandali (b) Madhav Kandali (c) Harivara Vipra (d) Hema Saraswati 9. Which Swargadeo shifted the capital of the Ahom Kingdom from Garhgaon to Rangpur (a) Gadhar Singha (b) Rudra Singha (c) Siva Singha (d) None of them 10. Borphukans were from the following community (a) Chutias (b) Mech (c) Ahoms (d) Kacharis 11. Who founded the Assam Association in 1903? (a) Manik Chandra Baruah (b) Jaggannath Baruah (c) Navin Chandra Bordoloi (d) None of them 12. Phulaguri uprising, first ever peasant movement in India that occurred in middle Assam in which year? (a) 1861 (b) 1857 (c) 1879 (d) 1836 13. -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings.