Increasing Access to Family Justice Through Comprehensive Entry Points and Inclusivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Education of a Judge Begins Long Before Judicial Appointment

T H E EDUCATION O F A JUD G E … The Honourable Brian Lennox, Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice The education of a judge begins long before judicial appointment. Judges are first and foremost lawyers. In Canada, that means that they typically have an undergraduate university degree1, followed by a three‐year degree from a Faculty of Law, involving studies in a wide variety of legal subjects, including contracts, real estate, business, torts, tax law, family, civil and criminal law, together with practice‐ oriented courses on the application of the law. The law degree is followed by a period of six to twelve months of practical training with a law firm. Before being allowed to work as a lawyer, the law school graduate will have to pass a set of comprehensive Law Society exams on the law, legal practice and ethics. In total, most lawyers will have somewhere between seven and nine years of post‐high school education when they begin to practice. It is not enough to have a law degree in order to be appointed as a judge. Most provinces and the federal government2 require that a lawyer have a minimum of 10 years of experience before being eligible for appointment. It is extremely rare that a lawyer is appointed as a judge with only 10 years’ experience. On average, judges have worked for 15 to 20 years as a lawyer before appointment and most judges are 45 to 52 years of age at the time of their appointment. They come from a variety of backgrounds and experiences and have usually practised before the courts to which they are appointed. -

National Directory of Courts in Canada

Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE National Directory of Courts in Canada August 2000 Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Statistics Statistique Canada Canada How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Information and Client Service, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (telephone: (613) 951-9023 or 1 800 387-2231). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our Web site. National inquiries line 1 800 263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1 800 363-7629 Depository Services Program inquiries 1 800 700-1033 Fax line for Depository Services Program 1 800 889-9734 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Web site www.statcan.ca Ordering and subscription information This product, Catalogue no. 85-510-XPB, is published as a standard printed publication at a price of CDN $30.00 per issue. The following additional shipping charges apply for delivery outside Canada: Single issue United States CDN $ 6.00 Other countries CDN $ 10.00 This product is also available in electronic format on the Statistics Canada Internet site as Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE at a price of CDN $12.00 per issue. To obtain single issues or to subscribe, visit our Web site at www.statcan.ca, and select Products and Services. All prices exclude sales taxes. The printed version of this publication can be ordered by • Phone (Canada and United States) 1 800 267-6677 • Fax (Canada and United States) 1 877 287-4369 • E-mail [email protected] • Mail Statistics Canada Dissemination Division Circulation Management 120 Parkdale Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0T6 • And, in person at the Statistics Canada Reference Centre nearest you, or from authorised agents and bookstores. -

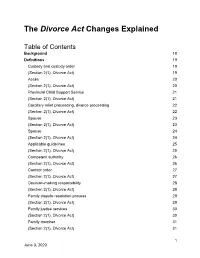

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

COVID-19 Guide: In-Person Hearings at the Federal Court

COVID-19 Guide: In-person Hearings at the Federal Court OVERVIEW This guide seeks to outline certain administrative measures that are being taken by the Court to ensure the safety of all individuals who participate in an in-person-hearing. It is specifically directed to the physical use of courtrooms. For all measures that are to be taken outside of the courtroom, but within common areas of a Court facility, please refer to the guide prepared by the Courts Administrative Service, entitled Resuming In-Person Court Operations. You are also invited to view the Court’s guides for virtual hearings. Additional restrictions may apply depending on the evolving guidance of the local or provincial public health authorities, and in situations where the Court hearing is conducted in a provincial or territorial facility. I. CONTEXT Notwithstanding the reopening of the Court for in-person hearings, the Court will continue to schedule all applications for judicial review as well as all general sittings to be heard by video conference (via Zoom), or exceptionally by teleconference. Subject to evolving developments, parties to these and other types of proceedings are free to request an in-person hearing1. In some instances, a “hybrid” hearing, where the judge and one or more counsel or parties are in the hearing room, while other counsel, parties and/or witnesses participate via Zoom, may be considered. The measures described herein constitute guiding principles that can be modified by the presiding Judge or Prothonotary. Any requests to modify these measures should be made as soon as possible prior to the hearing, and can be made by contacting the Registry. -

9780470736821.C01.Pdf

Includes the Family Law Act, Child Support Guidelines, Divorce Act, Arbitration Act, and Arbitration Act Regulations CANADIAN FAMILY LAW An indispensable, clearly written guide to Canadian law on • marriage • separation • divorce • spousal and child support • child custody and access • property rights • estate rights • domestic contracts • enforcement • same-sex relationships • alternate dispute resolution MALCOLM C. KRONBY Kronby_10thE_Book.indb 1 06/11/09 8:58 AM Copyright © 2010 by Malcolm C. Kronby All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed in writing to The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free 1-800-893-5777. Care has been taken to trace ownership of copyright material contained in this book. The publisher will gladly receive any information that will enable them to rectify any reference or credit line in subsequent editions. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in re- gard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kronby, Malcolm C., 1934- Canadian family law / Malcolm C. Kronby.—10th ed. -

Private Law As Constitutional Context for Same-Sex Marriage

Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage ROBERT LECKEY * While scholars of gay and lesbian activism have long eyed developments in Canada, the leading Canadian judgment on same-sex marriage has recently been catapulted into the field of vision of comparative constitutionalists indifferent to gay rights and matrimonial matters more generally. In his irate dissent in the case striking down a state sodomy law as unconstitutional, Scalia J of the United States Supreme Court mentions Halpern v Canada (Attorney General).1 Admittedly, he casts it in an unfavourable light, presenting it as a caution against the recklessness of taking constitutional protection of homosexuals too far.2 Still, one senses from at least the American literature that there can be no higher honour for a provincial judgment from Canada — if only in the jurisdictional sense — than such lofty acknowledgement that it exists. It seems fair, then, to scrutinise academic responses to the case for broader insights. And it will instantly be recognised that the Canadian judgment emerged against a backdrop of rapid change in the legislative and judicial treatment of same-sex couples in most Western jurisdictions. Following such scrutiny, this paper detects a lesson for comparative constitutional law in the scholarly treatment of the recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada. Its case study reveals a worrisome inclination to regard constitutional law, especially the judicial interpretation of entrenched rights, as an enterprise autonomous from a jurisdiction’s private law. Due respect accorded to calls for comparative constitutionalism to become interdisciplinary, comparatists would do well to attend,intra disciplinarily, to private law’s effects upon constitutional interpretation. -

CHILD SUPPORT: by JUDICIAL DECISION by LEGISLATION? (Pt

REFORM OF THE LAW CHILD SUPPORT: BY JUDICIAL DECISION BY LEGISLATION? (Pt. I) Alastair Dissett-Johnson* Dundee This isa two-partarticle. Partone analyses the recent Supreme Court ofCanada decision in Willick and the Provincial Appeal Court decisions in L6vesque and Edwards on the issue ofassessing child support. Part two examines the British Child Support Acts 1991-5, which introduced an administrative formula driven method ofassessing child support, and the Canadian Federal/Provincial Family Law Committees Report Recommendations on Child Support. The merits and problems associated with administrative andjudicial methods ofassessing child support are examined and contrasted. Il s'agit d'un article en deux parties. La première partie analyse la décision récente de la Cour suprême du Canada dans l'affaire Willick, ainsi que les décisions de la Cour d'appelprovinciale dans les affaires Lévesque etEdward qui évaluent laprotection sociale de l'enfant. La secondepartie examine, d'unepart, les Child Support Acts britanniques (Lois sur la protection sociale de l'enfant) votées de 1991 à 1995 et quiontintroduit des moyens administratifs, basés surune formule, permettant d'évaluer laprotection sociale de l'enfant et, d'autre part, le Rapport des comités sur la législationfamilialefédérale/provinciale canadienne et les recommandations concernant la protection sociale de l'enfant. Les aspects positifs et négatifsliésaux méthodesadministratives etjudiciairesd'évaluation de la protection sociale de l'enfant sont examinés. I. Introduction .... ........ -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

Submission to the Saskatchewan Provincial Court Commission November 2011

SSuubbmmiissssiioonn ttoo tthhee SSaasskkaattcchheewwaann PPrroovviinncciiaall CCoouurrtt CCoommmmiissssiioonn Saskatchewan Provincial Court Judges Association November 21, 2011 2011 Provincial Court Commission November 2011 Submission of the The Saskatchewan Provincial Court Judges’ Association Table of Contents Page Part I Introduction . .. 1 Part II Provincial Court Of Saskatchewan – An Overview . 2 A. Circuit Map . 3.1 Part III Mandate of the Provincial Court Commission . 7 Part IV Factors for Consideration . 13 A. The Trial Judges’ Role and Judicial Independence . 13 1. Responsibilities of a Trial Court Judge . 13 2. The Provincial Court and Judicial Independence . 19 3. The Work of the Provincial Court. .22 i. Criminal Jurisdiction . 23 ii. New Offences and Legislative Requirements . 25 iii. Criminal Division Workload . 35 a) The Judicial Complement . 35 b) Crime Rate in Saskatchewan . .37 iv. Civil Jurisdiction . .40 v. Family Jurisdiction . .46 vi. Youth Criminal Justice Act Jurisdiction . 47 vii. The Public We Serve . 49 a) Unrepresented and Self Represented Persons . 49 b) First Appearances in Provincial Court . .50 i SPCJA Submission to the Saskatchewan Provincial Court Commission November 2011 c) Emotional Problems, Learning Disorders and Mental Health Disabilities . .51 d) Literacy Problems . 52 e) Gladue Inquiries. 52 f) French Trials and Interpreters. 52 h) Spotlight in the Media. 53 viii. Accessibility . .57 B. Attracting the Most Qualified Applicants. .63 1. Tax Implications for Private Practitioners . 76 C. Economic and Market Factors. .78 1. Saskatchewan - Leading the Nation . 78 2. Cost of Living in Saskatchewan. .82 D. Salaries Paid to Other Trial Judges in Saskatchewan . 84 E. Salaries Paid to Other Trial Judges in Canada. 90 Part V Recommendations . -

Familysource®

FamilySource® What’s in FamilySource® CASE LAW • Western Weekly Reports (W.W.R.) 1911- report series of other commercial • Historical Report Series publishers, including Quebec cases of FamilySource contains all full text cases dealing national importance. These law report • Alberta Law Reports (Alta. L.R.) 1908-33 with family law from the Westlaw Canada case series include: Decisions published law collection. This collection includes: • Canadian Cases on the Law of in major law report series of other Securities (C.C.L.S.) 1994-1998 commercial publishers, including • Complete coverage of reported • Canadian Intellectual Property Quebec cases of national importance. Canadian court decisions from the Reports (C.I.P.R.) 1984-90 These law report series include: common law provinces and Quebec cases of national importance, from • Canadian Reports, Appeal Cases • A.R. Alberta Reports 1986 and continuing forward (C.R.A.C.) 1871-78; 1912-13 • Alta. L.R.B.R. Alberta Labour Relations • Complete coverage of reported Supreme • Coutlee’s Canada Supreme Court Board Reports Court of Canada and Privy Council Cases (Cout. S.C.) 1875-1906 • B.C.A.C. British Columbia Appeal Cases decisions originating in any province • Eastern Law Reporter (E.L.R.) 1906-14 • C.C.C. Canadian Criminal Cases or territory from 1876 forward • Fox Patent Cases (Fox Pat.C.) 1940-71 • C.H.R.R. Canadian Human Rights Reporter • Complete coverage of Federal Court • Maritime Provinces Reports • C.I.R.B. Canada Industrial Relations Board decisions reported in the Federal Court (M.P.R.) 1929-68 • C.L.L.C. Canadian Labour Law Cases Reports from 1971 forward, and of the • New Brunswick Reports (N.B.R.) 1867-1929 Exchequer Court from 1875 through • C.L.R.B.R. -

Museums and Photography: Some Observations

MUSEUMS AND PHOTOGRAPHY Museums and Photography: Some Observations By Carol Payne Today, photographs are fundamental few examples and tendencies and hope tools through which museums manage that these preliminary remarks will draw collections, provide didactic information, attention to the growing and dynamic promote themselves and engage relationship between Canadian museums audiences; just as visitors often participate and photographs at this important in museums through a camera lens and moment. social media. Photography is a mainstay in Canadian museums. The Canadian “Museum Latecomers” Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, for example, fosters an awareness of the The current surge of photography thousands of immigrants who arrived in exhibitions, festivals and collections Halifax through photographic portraits; is a relatively recent international Sight Unseen, the current Canadian phenomenon. British scholars Elizabeth Museum of Human Rights exhibition, Edwards and Christopher Morton recently paradoxically, uses smart phone cameras noted, “Photographs are museum and new software applications to make latecomers”; they generally “occupied an visual displays accessible to the seeing- ambiguous space between institutional impaired; and across the country digital and personal property, between photographs document myriad object historical document and transient or collections, making them available in- disposable record, both materially and house and online. intellectually.”1 Although there were a few notable exceptions, including the Carol Payne is associate professor of As the most popular form of visual Museum of Modern Art and the George Art History at Carleton University and a media in the early twenty-first century, Eastman House International Museum former curator at the Canadian Museum photography is enmeshed in the art, of Photography; museums usually of Contemporary Photography. -

Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments

Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments Report on the 2021 Process July 28, 2021 Independent Advisory Board for Comité consultatif indépendant Supreme Court of Canada sur la nomination des juges de la Judicial Appointments Cour suprême du Canada July 28, 2021 The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau Prime Minister of Canada 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A2 Dear Prime Minister: Pursuant to our Terms of Reference, the Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments submits this report on the 2021 process, including information on the mandate and the costs of the Advisory Board’s activities, statistics relating to the applications received, and recommendations for improvements to the process. We thank you for the opportunity to serve on the Advisory Board and to participate in such an important process. Respectfully, The Right Honourable Kim Campbell, C.P., C.C., O.B.C., Q.C. Chairperson of the Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments Advisory Board members: David Henry Beverley Noel Salmon Signa A. Daum Shanks Jill Perry The Honourable Louise Charron Erika Chamberlain Independent Advisory Board for Comité consultatif indépendant Supreme Court of Canada sur la nomination des juges de la Judicial Appointments Cour suprême du Canada Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Establishment of the Advisory Board and the