Parents' Rights in the Canadian Constitutional Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

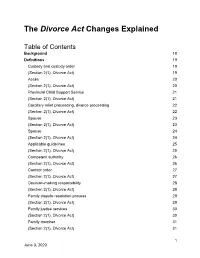

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

Private Law As Constitutional Context for Same-Sex Marriage

Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage ROBERT LECKEY * While scholars of gay and lesbian activism have long eyed developments in Canada, the leading Canadian judgment on same-sex marriage has recently been catapulted into the field of vision of comparative constitutionalists indifferent to gay rights and matrimonial matters more generally. In his irate dissent in the case striking down a state sodomy law as unconstitutional, Scalia J of the United States Supreme Court mentions Halpern v Canada (Attorney General).1 Admittedly, he casts it in an unfavourable light, presenting it as a caution against the recklessness of taking constitutional protection of homosexuals too far.2 Still, one senses from at least the American literature that there can be no higher honour for a provincial judgment from Canada — if only in the jurisdictional sense — than such lofty acknowledgement that it exists. It seems fair, then, to scrutinise academic responses to the case for broader insights. And it will instantly be recognised that the Canadian judgment emerged against a backdrop of rapid change in the legislative and judicial treatment of same-sex couples in most Western jurisdictions. Following such scrutiny, this paper detects a lesson for comparative constitutional law in the scholarly treatment of the recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada. Its case study reveals a worrisome inclination to regard constitutional law, especially the judicial interpretation of entrenched rights, as an enterprise autonomous from a jurisdiction’s private law. Due respect accorded to calls for comparative constitutionalism to become interdisciplinary, comparatists would do well to attend,intra disciplinarily, to private law’s effects upon constitutional interpretation. -

CHILD SUPPORT: by JUDICIAL DECISION by LEGISLATION? (Pt

REFORM OF THE LAW CHILD SUPPORT: BY JUDICIAL DECISION BY LEGISLATION? (Pt. I) Alastair Dissett-Johnson* Dundee This isa two-partarticle. Partone analyses the recent Supreme Court ofCanada decision in Willick and the Provincial Appeal Court decisions in L6vesque and Edwards on the issue ofassessing child support. Part two examines the British Child Support Acts 1991-5, which introduced an administrative formula driven method ofassessing child support, and the Canadian Federal/Provincial Family Law Committees Report Recommendations on Child Support. The merits and problems associated with administrative andjudicial methods ofassessing child support are examined and contrasted. Il s'agit d'un article en deux parties. La première partie analyse la décision récente de la Cour suprême du Canada dans l'affaire Willick, ainsi que les décisions de la Cour d'appelprovinciale dans les affaires Lévesque etEdward qui évaluent laprotection sociale de l'enfant. La secondepartie examine, d'unepart, les Child Support Acts britanniques (Lois sur la protection sociale de l'enfant) votées de 1991 à 1995 et quiontintroduit des moyens administratifs, basés surune formule, permettant d'évaluer laprotection sociale de l'enfant et, d'autre part, le Rapport des comités sur la législationfamilialefédérale/provinciale canadienne et les recommandations concernant la protection sociale de l'enfant. Les aspects positifs et négatifsliésaux méthodesadministratives etjudiciairesd'évaluation de la protection sociale de l'enfant sont examinés. I. Introduction .... ........ -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

Familysource®

FamilySource® What’s in FamilySource® CASE LAW • Western Weekly Reports (W.W.R.) 1911- report series of other commercial • Historical Report Series publishers, including Quebec cases of FamilySource contains all full text cases dealing national importance. These law report • Alberta Law Reports (Alta. L.R.) 1908-33 with family law from the Westlaw Canada case series include: Decisions published law collection. This collection includes: • Canadian Cases on the Law of in major law report series of other Securities (C.C.L.S.) 1994-1998 commercial publishers, including • Complete coverage of reported • Canadian Intellectual Property Quebec cases of national importance. Canadian court decisions from the Reports (C.I.P.R.) 1984-90 These law report series include: common law provinces and Quebec cases of national importance, from • Canadian Reports, Appeal Cases • A.R. Alberta Reports 1986 and continuing forward (C.R.A.C.) 1871-78; 1912-13 • Alta. L.R.B.R. Alberta Labour Relations • Complete coverage of reported Supreme • Coutlee’s Canada Supreme Court Board Reports Court of Canada and Privy Council Cases (Cout. S.C.) 1875-1906 • B.C.A.C. British Columbia Appeal Cases decisions originating in any province • Eastern Law Reporter (E.L.R.) 1906-14 • C.C.C. Canadian Criminal Cases or territory from 1876 forward • Fox Patent Cases (Fox Pat.C.) 1940-71 • C.H.R.R. Canadian Human Rights Reporter • Complete coverage of Federal Court • Maritime Provinces Reports • C.I.R.B. Canada Industrial Relations Board decisions reported in the Federal Court (M.P.R.) 1929-68 • C.L.L.C. Canadian Labour Law Cases Reports from 1971 forward, and of the • New Brunswick Reports (N.B.R.) 1867-1929 Exchequer Court from 1875 through • C.L.R.B.R. -

Interacting with Separating, Divorcing, Never-Married Parents and Their Children

Association of Family and Conciliation Courts An Educator’s Guide: Interacting with Separating, Divorcing, Never-Married Parents and Their Children © 2009 Association of Family and Conciliation Courts AN EDUCATOR’S GUIDE: INTERACTING WITH SEPARATING, DIVORCING, NEVER- MARRIED PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN AFCC work group: Barbara Steinberg, Ph.D., Chair Nancy Olesen, Ph.D., Reporter Deborah Datz, LPC, NCSP Jake Jacobson, LCSW Naomi Kauffman, J.D. Hon. Emile Kruzick Shelley Probber, Psy.D. Gary Rick, Ph.D. With special thanks for contributed materials to Marsha Kline Pruett, PH.D., M.S.L. and The Smith Richardson Foundation, Inc. This guide was developed by the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts to help educators address the needs of separating, divorcing and never-married families and their children. AFCC is an international, multi- disciplinary organization comprised of attorneys, judges, mediators and mental health care providers who are dedicated to improving the lives of children and families through the resolution of family conflict. © 2009 Association of Family and Conciliation Courts TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................ 4 Children: Recognizing Their Challenges ................................................ 5 Parents: Facilitating Their Involvement ................................................. 7 Teachers: Staying Out of the Middle....................................................... 12 Family Court Professionals: Who Wants What -

Domestic Contracts

5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 1 FAMILY LAW FOR WOMEN IN ONTARIO Domestic Contracts All Women. One Family Law. Know your Rights. 5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 2 Canadian Council of Muslim Women (CCMW) has prepared this information to provide Muslim women with basic information about family law in Ontario as it applies to Muslim communities. We hope to give answers to key questions about whether Muslim family laws can be used to resolve family law disputes in Canada. 2 DOMESTIC CONTRACTS 5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 3 Domestic Contracts This booklet is meant to give you a basic understanding of legal issues. It is not a substitute for individual legal advice and assistance. If you are dealing with family law issues, get legal advice as soon as possible to protect your rights. For more information about how to find and pay for a family law lawyer, see FLEW’s booklet on “Finding Help with your Family Law Problem” on FLEW’s website at www.onefamilylaw.ca. Domestic contracts are legal agreements about intimate relationships. Marriage contracts, cohabitation agreements and separation agreements are different kinds of domestic contracts. You can use domestic contracts to set out certain terms for your relationship. You can also use a domestic contract to agree on your and your spouse’s rights and responsibilities in case your relationship ends. CANADIAN COUNCIL OF MUSLIM WOMEN (CCMW) 3 5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 4 Domestic contracts are not legal unless they are in writing. -

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Family Service Delivery: Disease

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Family Service Delivery: Disease, Prevention, and TTreatment Noel Semple Law Commission of Ontario Family Law Process Projjectt Final Paper June 23, 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction, Outline and Methodology ......................................................................... 3 I. A. Subject Matter: the Families and the Challenges Under Examination Here ......... 4 I. B. Unit of Analysis: Individual or Family? .................................................................. 5 I. C. The role of choice in the formation of family ......................................................... 6 I. D. Evaluative Tool: Cost-Benefit Analysis ................................................................. 9 I.D.1. Applying CBA Methodology to Family Challenges: Limitations ..................... 11 I.D.2. Applying CBA to Family Challenges: Potential ............................................. 13 II. Family Challenges ..................................................................................................... 14 II. A. Economic Vulnerability of Canadian Families.................................................... 16 II. B. Sacrifices in Earning Potential Undertaken in Intact Families............................ 19 II. B. 1. How Family Life can Lead to Sacrifices in Individual Earning Potential ..... 19 II. B. 2. Quantifying Parenting ................................................................................ 21 II. B. 3. Persistence of Gender Patterns ................................................................ -

Family Law and Immigrants a HANDBOOK on FAMILY LAW ISSUES in NEW BRUNSWICK

30 30 25 20 20 20 20 15 15 10 10 10 0 2014 2015 2016 Family Law and Immigrants A HANDBOOK ON FAMILY LAW ISSUES IN NEW BRUNSWICK PUBLIC LEGAL EDUCATION AND INFORMATION SERVICE OF NEW BRUNSWICK Public Legal Education and Information Service of New Brunswick (PLEIS-NB) is a non-profit charitable organization. Our mission is to provide plain language law information to people in New Brunswick. PLEIS-NB receives funding and in-kind support from Department of Justice Canada, the New Brunswick Law Foundation and the New Brunswick Office of the Attorney General. Project funding for the development of this booklet was provided by the Supporting Families Fund, Justice Canada. We wish to thank the many organizations and individuals who contributed to the development of this handbook. We appreciate the suggestions for content that were shared by members of the Law Society of New Brunswick. We also thank the community agencies who work with newcomers and immigrants who helped us identify some unique issues that immigrants may face when dealing with family law matters. A special thanks as well to the individuals who participated in the professional review of the content, both from the perspective of legal accuracy, as well as relevance and cultural sensitivity. PLEIS-NB wishes to acknowledge the following agencies for giving permission to make use of, or adapt their existing information on family law and immigration status for this handbook: • Community Legal Education Ontario (CLEO) • Family Law Education for Women (FLEW) • METRAC – Action on Violence • Government of Canada, Global Affairs Canada • Government of Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship • Justice Education Society of BC • Legal Services Society British Columbia • Luke’s Place • Springtide Resources We have flagged this assistance throughout and the full list of agencies cited can be found on our Resources Cited section. -

Legislative Background

Legislative Background: An Act to amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act and to make consequential amendments to another Act (Bill C-78 in the 42nd Parliament) June 2019 June 2019 Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 4 A. DIVISION OF FEDERAL AND PROVINCIAL RESPONSIBILITIES FOR FAMILY LAW .................. 4 B. CHALLENGES FACING THE FAMILY JUSTICE SYSTEM ........................................................... 5 1. Outdated federal family laws ........................................................................................... 5 2. Access to justice ............................................................................................................... 6 3. Contentious issues in family law ...................................................................................... 7 OVERVIEW: LEGISLATIVE OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................ 7 A. PROMOTING THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE CHILD ............................................................... 7 1. Exclusive focus on the best interests of the child in parenting matters .......................... 8 2. Best interests criteria (Clause 12) ................................................................................... -

FAMILY LAW NEWSLETTER Published by the Family Law Section of the Oregon State Bar

FAMILY LAW NEWSLETTER Published by the Family Law Section of the Oregon State Bar Vol. 32, No. 1 February 2013 Winning and Losing When Dividing PERS Benefits CONTENTS By David W. Gault, QDRO Specialist and Certified Divorce Financial Analyst, Jones & Roth, CPAs & Business Consultants ArtICLES Despite a well written and wonderfully informative pair of articles authored by Clark B. Williams appearing in the 2011 Winning and Losing When Dividing PERS April and June issues of the OSB Family Law Newsletter, many Benefits family law practitioners appear to have not yet taken the time to By David W. Gault.......................1 give those articles the close reading they deserve. Those who do Parenting Time & Shared Residential Custody: will come to recognize that a significant advantage can result Ten Common Myths from making an informed choice between two acceptable By Dr. Linda Nielsen .....................2 methods of dividing pension benefits of Tier One and Tier Two PERS members. Index of Articles: 2012 OSB Family Law Newsletter ............................6 We would like to offer here a very capsulized summary and recommend that the reader digest the full discussion provided in MILItarY faMILY law those articles. Hidden Money in Military Divorce Cases Tier One and Tier Two accounts carry what are termed By Mark E. Sullivan .....................8 “Member Account Balances”, although those do not represent the entire value of the pension. Traditionally, the approach to CASENOTES division was to first isolate the marital portion (which might or Supreme Court........................12 might not be 100%) and then transfer 50% of the marital portion to a separate account in the name of the nonmember spouse. -

Privatizing Family Law in the Name of Religion

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 18 (2009-2010) Issue 4 Symposium: Families, Fundamentalism, Article 6 & the First Amendment May 2010 Privatizing Family Law in the Name of Religion Robin Fretwell Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Family Law Commons Repository Citation Robin Fretwell Wilson, Privatizing Family Law in the Name of Religion, 18 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 925 (2010), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol18/iss4/6 Copyright c 2010 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj PRIVATIZING FAMILY LAW IN THE NAME OF RELIGION Robin Fretwell Wilson* In pockets across the world, a movement has quietly taken hold to allow funda- mentalist1 religious norms, rather than state law, to govern family matters like divorce and inheritance. Many of these religious norms depart significantly from the state’s background rules protecting individuals. Nonetheless, fundamentalist religious understandings are given the force of law, either by treating them as binding judg- ments arrived at through arbitration or by delegating jurisdiction to religious groups to decide family disputes, with nominal state oversight. This Essay explores the risks to two traditionally vulnerable groups, women and children, when the state delegates its traditional oversight of the family to religious authorities.2 To surface these risks, this Essay draws on two lived experiences of reli- gious deference around the world. Specifically, this Essay examines the eighty-five * Class of 1958 Law Alumni Professor of Law, Washington and Lee University School of Law.