Medicaid Kaiser Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cy Martin Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Cy Martin Collection Martin, Cy (1919–1980). Papers, 1966–1975. 2.33 feet. Author. Manuscripts (1968) of “Your Horoscope,” children’s stories, and books (1973–1975), all written by Martin; magazines (1966–1975), some containing stories by Martin; and biographical information on Cy Martin, who wrote under the pen name of William Stillman Keezer. _________________ Box 1 Real West: May 1966, January 1967, January 1968, April 1968, May 1968, June 1968, May 1969, June 1969, November 1969, May 1972, September 1972, December 1972, February 1973, March 1973, April 1973, June 1973. Real West (annual): 1970, 1972. Frontier West: February 1970, April 1970, June1970. True Frontier: December 1971. Outlaws of the Old West: October 1972. Mental Health and Human Behavior (3rd ed.) by William S. Keezer. The History of Astrology by Zolar. Box 2 Folder: 1. Workbook and experiments in physiological psychology. 2. Workbook for physiological psychology. 3. Cagliostro history. 4. Biographical notes on W.S. Keezer (pen name Cy Martin). 5. Miscellaneous stories (one by Venerable Ancestor Zerkee, others by Grandpa Doc). Real West: December 1969, February 1970, March 1970, May 1970, September 1970, October 1970, November 1970, December 1970, January 1971, May 1971, August 1971, December 1971, January 1972, February 1972. True Frontier: May 1969, September 1970, July 1971. Frontier Times: January 1969. Great West: December 1972. Real Frontier: April 1971. Box 3 Ford Times: February 1968. Popular Medicine: February 1968, December 1968, January 1971. Western Digest: November 1969 (2 copies). Golden West: March 1965, January 1965, May 1965 July 1965, September 1965, January 1966, March 1966, May 1966, September 1970, September 1970 (partial), July 1972, August 1972, November 1972, December 1972, December 1973. -

Maine Developments, January 1966 Maine Department of Economic Development

Maine State Library Digital Maine Economic and Community Development Economic and Community Development Documents 1-1-1966 Maine Developments, January 1966 Maine Department of Economic Development Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/decd_docs Recommended Citation Maine Department of Economic Development, "Maine Developments, January 1966" (1966). Economic and Community Development Documents. 114. https://digitalmaine.com/decd_docs/114 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Economic and Community Development at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economic and Community Development Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAIN! Department of Economic Development • Augusta, Maine • Standish K. Bachman, Commissioner Vol. 5 No.1 January, 1966 COORDINATOR Governor John H. Reed has appointed MAINE'S ECONOMIC PROGRESS Richard A. Hebert of the DED staff to be Federal projects coordinator for his office. BY Hebert will be on assignment loan to the Executive Department and will report STANDISH K. BACHMAN, Commissioner directly to the Governor and to Steven D. DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC DEVEWPMENT Shaw, Administrative Assistant to the Governor. Maine stands at the dawning of a new Great strides are being made in our high- The veteran DED staffer has been with year. On the basis of what transpired in the Department since its creattion in 1955 ways system. Route 95 was completed from the year just ended, I look for 1966 to bring Old Town to Howland, on its way to Houl- and served as administrative assistant to continued economic progress to our state. -

1953 1952 1955 1954 1957 1956 1959 1958 1961

I. Edward Block retired as The Richard C. DiPrima Prize Managing Director of was established in December SIAM in September 1994, 1985 to commemorate the and he was replaced by former SIAM president. James Crowley, who was named as SIAM’s The JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR Executive Director. In January 2001, the society INDUSTRIAL AND APPLIED appointed a representative in By the fall MATHEMATICS was renamed Washington, DC to act on of 1954, the SIAM JOURNAL ON APPLIED The Society for Industrial and In May 1969, the behalf of its members. SIAM had MATHEMATICS in January 1966. SIAM released the Applied Mathematics (SIAM) was society released its The SIAM Journal on The society released 500 members and sections had The society co-sponsored first volume in its incorporated as a non-profit first volume in the Optimization made its debut its Mathematics in been formed in New York City, San the first Gatlinburg Around 1978, SIAM initiated SIAM co-sponsored the First In July 1989, the society MONOGRAPHS ON organization under the laws of the book series, SIAM- in February 1991. Industry report in 1996. Francisco and Washington, DC. symposium on numerical its focused-conference International Congress on moved into its new offices DISCRETE MATHEMATICS State of Delaware on April 30, 1952. AMS Proceedings. SIAM held a record-setting, On December 28, 1954, SIAM held linear algebra in April 1961. program to concentrate on In July 1980, SIAM moved its international celebration to mark Industrial and Applied at 3600 Science Center, in In December 1996, a AND APPLICATIONS, and In 1959, the society published the SIAM published the first volume its first national meeting. -

Analysis of the Lexington, Kentucky Housing Market

728.1 :308 r22 ]966 L+rn6tot1 Ka W"lfi"e I l, I LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY HOUSING MARKET as of January I, 1966 A Report by the DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT FED ERAt HOUSING ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D. C.2O1I1 JUrY 1966 a ANALYSIS OF THE LEXINGTON KENTUCKY HOI]SING MARKET AS OF JANUARY I t966 FIELD MAR.KET ANALYSIS SERVICE FEDERAL HOUSING ADMINI STRATION DEPARTT"IENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMM.IT Foreword As a publlc servlce to assist local houslng actlvitles through clearer understanding of local housing market conditions, FHA lnttiated publlcatlon of lts comprehenslve housing market analyeee early ln 1965. Wht[e each report ls deslgned speclfically for FHA use in administerlng lts mortgage lnsurance operations, 1t ls expected that the factual lnformatlon and the findings and concluslons of these reports wl1l be generally useful also to bullders, mortgagees, and others concerned with local housing problems and to others havlng an lnterest in local economlc con- dlttons and trends. Stnce market analysls 1s not an exact science the judgmental factor 1s lmportant tn the development of flndlngs and conclusions. There wlll, of course, be dlfferences of oplnlon ln the lnter- pretatlon of avallabl.e factual lnfornatton 1n determlning the absorptlve capaclty of the market and the requirements for maln- tenance of a reasonable balance ln deuand-supply relatlonshlps. The factual framework for each analysts 1s developed as thoroughly as posslble on the basis of inforrnatton avallable from both local and national sources. Unless speclflcally identifled by source reference, all estlmates and judgments ln the analygls are those of the authorlng analyst. -

™E Items-In-Secretary-General's Statements - XI, 4 January 1966 - 5 May 1966

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 20 Date 22/05/2006 Time 4:29:40 PM S-0886-0004-03-00001 Expanded Number S-0886-0004-03-00001 ™e Items-in-Secretary-General's statements - XI, 4 January 1966 - 5 May 1966 Date Created 21/03/1966 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0886-0004: United Nations Documents of the Secretary-General: U Thant: Secretary-General's Statements Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit UNITED NATIONS Press Services Office of Public Information United Nationst N.Y. (JOE USE OF INFORMATION MEDIA — NOT AN OFFICIAL RECORD) Press Release SG/SM/502 5 May 1966 STATEMENT BY SECRETARY-GENERAL AT HEW YORK AIRPORT OH 5 MAY Following is the text of a statement made by the Secretary-General, U Thant, on arrival at New York airport on 5 May from Geneva: "I have nothing new to add on my return from Europe, since my press officer has been dispatching daily reports to Headquarters. The primary purpose of my visit to Europe was to attend the Administrative Committee on Co-ordination (ACC) meetings in London and to address the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, but the Government of the United Kingdom and the Government of France very kindly invited me to be their guest. "During my stay in London and Paris I took the opportunity of discussing several matters of interest with the leaders of the two countries. Naturally, in the course of our discussions, political issues such as Viet-Nam came up prominently. In London, of course, we discussed,besides Viet-Nam, the questions of Cyprus and Rhodesia. -

ORDER of 23 NOVEMBER 1966 Mode Officiel De Citation: Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, Ordonnance Du 23 Novembre 1966, C.I.J

COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE RECUEIL DES ARRÊTS, AVIS CONSULTATIFS ET ORDONNANCES AFFAIRE DE LA BARCELONA TRACTION, LIGHT AND POWER COMPANY, LIMITED (NOUVELLE REQUÊTE : 1962) (BELGIQUE c. ESPAGNE) ORDONNANCE DU 23 NOVEMBRE 1966 INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REPORTS OF JUDGMENTS, ADVISORY OPINIONS AND ORDERS CASE CONCERNING THE BARCELONA TRACTION, LIGHT AND POWER COMPANY, LIMITED (NEW APPLICATION: 1962) (BELGIUM v. SPAIN) ORDER OF 23 NOVEMBER 1966 Mode officiel de citation: Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, ordonnance du 23 novembre 1966, C.I.J. Recueil 1966, p. 507. Officia1 citation: Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, Order of 23 November 1966, I.C.J. Reports 1966, p. 507. No de vente : Sales number 304 1 INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE YEAR 1966 1966 23 November 1966 23 November General List : No. 50 CASE CONCERNING THE BARCELONA TRACTION, LIGHT AND POWER COMPANY, LIMITED (NEW APPLICATION : 1962) (BELGIUM v. SPAIN) ORDER The President of the International Court of Justice, Having regard to Article 48 of the Statute of the Court and to Article 37 of the Rules of Court, Having regard to the Order of 12 January 1966 fixing the time-limits for the filing of the Reply of the Government of Belgium and the Rejoin- der of the Government of Spain; Whereas, by a letter dated 7 October 1966 and received and filed in the Registry on 13 October 1966, the Agent for the Government of Belgium, for the reasons therein set out, requested an extension of six months of the time-limit, fixed at 30 November 1966, -

Special Libraries, November 1966

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1966 Special Libraries, 1960s 11-1-1966 Special Libraries, November 1966 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1966 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, November 1966" (1966). Special Libraries, 1966. 9. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1966/9 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1966 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. special libraries November 1966, vol. 57, no. 9 Information Networks Data Processing and the Library Audio-visual Orientation A Special Iwvitatiow tbat will save your library more than $1600 1 THE PERGAMON INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY CONTRACT PLAN Now, for the first time, you may obtain hardcover library editions of the Commonwealth and International Library at a considerable saving in time, and at discounts of up to 40%. ABOUT THE BOOKS This modern International Library is authored by distinguished international authori- ties. The books provide a concise treatment of topics ranging from science and tech- nology, to education, politics and the arts. They have received enthusiastic acclaim from educators, librarians, students, and the general reader. Under the Pergamon International Library Contract Plan all your costs go into books. There are no extra fees or hidden expenses. The liberal discounts over the next two and one half years require only a small yearly investment for a large volume of books. -

Generl Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

RESTRICTED L/2336/Add.2 GENERL AGREEMENT ON 10 May 1965 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution Original: English RESIDUAL IMPORT RESTRICTIONS Addendum DENMARK The Government of Denmarmk has submitted the following detailed plans for liberalization, as had been forecast in the basic Danish notification of residual import restrictions (L/2336, page 19). It is the intention of the Danish Government to abolish the remaining quan- titative import restrictions on goods listed from Chapter 25 to the end of the Brussels Nomenclature and restrictions on some goods listed in Chapters 17 to 21, not later than 31 December 1966, as shown in the following time-table for liberalization: Brussels Planned No. Description of commodity liberalization date ex 17.04 Liquorice confectionery except liquorice all sorts 1 July 1965 ex 17.04 Other sugar confectionery and liquorice all sorts 1 January 1966 ex 18.06 Chocolate 31 December 1966 ex 19.08 Biscuits, rusks 1 July 1966 ex 18.06 Other food preparations, also containing cocoa 31 December 1966 ex 21.07 ex 25.16 Granite in blocks and sheets 1 July 1965 35.05 ) Dextrins and dextrin glues; soluble or roasted 1 January 1966 ex 35.06 ) starches; starch glues and glues containing ) starch or starch products 40.10 Transmission, conveyor or elevator belts or belting 1 July 1965 of vulcanized rubber ex 40.11 Rubber tyres and tubes for bicycles without motor 1 July 1965 or with an auxiliary motor ex 46.03 Basketwork and other articles of plaiting materials 1 July 1966 ex 48.11 Wallpaper 1 July 1965 ex 64.01 ) Footwear with uppers of rubber, footwear on which 1 July 1966 ex 64.02 ) outer soles are vulcanized L/2336/Add.2 Page 2 Brussels Planned No. -

January 1964 Economic Report of the President

JANUARY 1964 ECONOMIC REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT HEARINGS BEFORE THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES EIGHTY-EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 23, 27, 28, and 29, 1964 PART 1 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 28-276 WASHINGTON: 1964 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office / Washington, D.C., 20402 -Price 70 cents JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE (Created pursuant to sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Cong.) PAUL H. DOUGLAS, Illinois, Chairman RICHARD BOLLING, Missouri, Vice Chairman SENATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JOHN SPARKMAN, Alabama WRIGHT PATMAN, Texas J. W. FULBRIGHT, Arkansas HALE BOGGS, Louisiana WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin HENRY S. REUSS, Wisconsin CLAIBORNE PELL, Rhode Island MARTHA W. GRIFFITHS, Michigan JACOB K. JAVITS, New York THOMAS B. CURTIS, Missouri JACK MILLER, Iowa CLARENCE E. KILBURN, New York LEN B. JORDAN, Idaho WILLIAM B. WIDNALL, New Jersey JAMES W. KNOWLEs, Executive Director MARn&N T. TRACY, Financial Clerk HAMILTON D. GEWEHR, Administratise Clerk ECONOMISTS W5LLIAM H. MOORE THOMAS H. Bones, JR. GERALD A. POLLACK ALAN P. MURRAY DONALD A. WEBSTER (Mlinority) _ II CONTENTS STATEMENTS JANUARY 23, 1964 Heller, Dr. Walter W., Chairman, Council of Economic Advisers, ac- Page companied by Gardner Ackley and John P. Lewis, members - 8 JANUARY 27, 1964 Gordon, Kermit, Director, Bureau of the Budget, accompanied by Elmer Staats, Deputy Director; Charles L. Schultze, Assistant Director; and Samuel M. Cohen, Deputy to the Assistant Director for Budget Review- 81 JANUARY 28, 1964 Dillon, Hon. Douglas, Secretary of the Treasury accompanied by Paul A. -

LACC Library Periodicals

- AAA - AWI QUARTERLY Current copy only ADMINISTRATIVE MANAGEMENT MF:March 1986-4th Qtr. 1988 ADOLESCENCE Winter 1967/68-Fall 1982 Spring 2001-Spring 2007 AFRICAN ARTS Autumn 1967-November 1983 ALBUMEN (L.A.C.C.)(Archives) #1: March 1972 AMERICA (National Catholic Weekly Review) January 1961- M:April 1909-December 1997 AMERICAN ARTIST January 1958-December 1982 January 1984-December 1985 January 1992-December 1992 AMERICAN CINEMATOGRAPHER February 1968-May 2012 AMERICAN CRAFT (Formerly CRAFT HORIZONS) June 1979-January 1992 AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW March 1985- December 1987 June 1995-December 1995 M:March 1960–December 1982 AMERICAN EDUCATOR Keep latest year AMERICAN HERITAGE December 1954-Summer 2012 AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW October 1929-April 1989 M:October 1959-December 1982 AMERICAN HISTORY ILLUSTRATED February 1971-January 1985 September 1988-February 1991 AMERICAN IMAGO Spring 1968-Winter 1978 Spring 1987- Winter 1988 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF NURSING January 1942-December 1988 January 1990-December 1990 January 1992-December 1992 August 1994-December 1995 January 1996-July 1997 April 2001- AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY January 1990-January 2012 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY M:July 1895-May 1959 * Shelved in Newspaper Stacks M: Microfilm MF: Microfiche 11/4/2019 1 AMERICAN LITERATURE January 1949-October 1982 AMERICAN MAGAZINE January 1943-June 1943 January 1945-June 1947 July 1948-June 1949 January 1950-June 1956 AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL MONTHLY January 1989-June/July 1999 AMERICAN MERCURY May 1924-December 1933 January 1937-January -

Extensions of Re.Marks C

22876 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-_ SENATE September 16, 1966 Assistant Director, Resource Management a NOMINATION of America to th:) 21st session of the General Assembly of the United Nations-; Gerald M. Kerr, May 1961 to May 1962. Executive nomination received by the . Eugene V. Zumwalt, J:.me 1962 to present. Mrs. Patricia Roberts Harris, of the District Senate September 16 (legislative day of of Columbia, to be alternate representative State director, California State office b September 7), 1966: of the United States of America to the 21st Raymond Best, September 1955 to May AsSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL session of the General . Assembly of the 1961. Harold Barefoot Sanders, Jr., of Texas, to United Nations. Neal D. Nelson, May 1961 to January 1966. be an Assistant Attorney General, vice John George L. Killion, of Californ~a. to be al ternate representative of the United States J. Russell Penney, January 1966 to present. W. Douglas, resigned. State director, Oregon State office b of America to the 21st session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. Virgil Heath, May 1955 to August 1959. Harding F. Bancroft, of New York, to be Russell E. Getty, August 1959 to June 1966. CONFffiMATIONS alternate representative of the United States James F. Doyle, June 1966 to present. of America to the 21st session of the Gen NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Executive nominations confirmed by eral Assembly of the United Nations. the Senate September 16 (legislative day Director INTER-AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK of September 7) , 1966 : Conrad L. Wirth, December 1951 to Jan- W. True Davis, Jr., of Missouri, to be Exec uary 1964. -

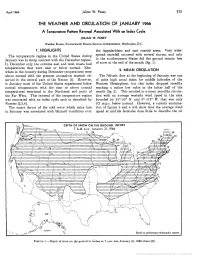

The Weather and Circulation of January 1966

April 1966 Julian W. Posey 215 THE WEATHER AND CIRCULATION OF JANUARY 1966 A Temperature Pattern Reversal Associated With an Index Cycle JULIAN W. POSEY Weather Bureau, Environmental Science Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 1. HIGHLIGHTS the Appalachians and east coastal areas. Very wide- The temperature regime in the United States during spread snowfall occurred with several storms, and only January was in sharp contrast with the December regime. in the southernmost States did the ground remain free In December only the extreme east and west coasts had of snow at the end of the month (fig. 1). temperatures that were near or below normal. Else- 2. MEAN CIRCULATION where in the country during December temperatures were above normal with the greatest anomalous warmth ob- The 700-mb. flow at the beginning of January was one served in the central part of the Nation [l]. However, of quite high zonal index for middle latitudes of the in January most of the United States experienced below Western Hemisphere, but this index dropped steadily normal temperatures with the near or above normal reaching a rather low value in the latter half of the temperatures restricted to the Northeast and parts of month (fig. 2). This resulted in a mean monthly circula- the Far West. This reversal of the temperature regime tion with an average westerly wind speed in the area was associated with an index cycle such as described by bounded by 35'-55' N. and 5'-175' W. that was only Namias [2,3,4]. 0.2 m.p.s. below normal.