Amending the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure Lester B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nancy Buenger Abstract

Nancy Buenger Abstract HOME RULE: EQUITABLE JUSTICE IN PROGRESSIVE CHICAGO AND THE PHILIPPINES ______________________________________________________________________________ The evolution of the US justice system has been predominantly parsed as the rule of law and Atlantic crossings. This essay considers courts that ignored, disregarded, and opposed the law as the United States expanded across the Pacific. I track Progressive home rule enthusiasts who experimented with equity in Chicago and the Philippines, a former Spanish colony. Home rule was imbued with double meaning, signifying local self-governance and the parental governance of domestic dependents. Spanish and Anglo American courts have historically invoked equity, a Roman canonical heritage, to more effectively administer domestic dependents and others deemed lacking in full legal capacity, known as alieni juris or of another’s right. Thomas Aquinas described equity as the virtue of setting aside the fixed letter of the law to expediently secure substantive justice and the common good. In summary equity proceedings, juryless courts craft discretionary remedies according to the dictates of conscience and alternative legal traditions—such as natural law, local custom, or public policy—rather than the law’s letter. Equity was an extraordinary Anglo American legal remedy, an option only when common law remedies were unavailable. But the common law was notably deficient in the guardianship of alieni juris. Overturning narratives of equity’s early US demise, I document its persistent jurisdiction over quasi-sovereign populations, at home and abroad. Equity, I argue, is a fundamental attribute of US state power that has facilitated imperial expansion and transnational exchange. Nancy Buenger Please do not circulate or cite without permission HOME RULE: EQUITABLE JUSTICE IN PROGRESSIVE CHICAGO AND THE PHILIPPINES _____________________________________________________________________________________ Progressive home rule enthusiasts recast insular and municipal governance at the turn of the twentieth century. -

Pursuant to the Call of the Chief Justice, Issued February 16, 1950, the Judicial Conference of the United States Met in Special Session on Thursday, March 9,1950

APPE~DIX REPORT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF A SPECIAL SESSION OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES Pursuant to the call of the Chief Justice, issued February 16, 1950, the Judicial Conference of the United States met in special session on Thursday, March 9,1950. The following were present: The Chief Justice, presiding. Circuit: District of Columbia: Chief Judge HAROLD M. SrrEPHENs. First: Chief Judge CALVERT MAGRUDER. Second: Chief Judge LEARNED HAND. Third: Chief Judge JOHN BIGGS, Jr. Fourth: Chief Judge JOHN J. PARKER. Fifth: Chief Judge JOSEtPH C. HUTCHESON, Jr. Sixth: Circuit Judge CHARLES C. SaIONs.* Seventh: Chief Judge J. EARL MAJOR. Eighth: Chief Judge ARCHIBALD K. GARDNER. Tenth: Chief Judge DRlE L. PHILLIPS. Hon. Arthur F. Lederle, Chief Judge, United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan; Hon. Finis J. Garrett, Chief Judge, United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals; ·Chief JudgE' Xenophon Hicks of the Sixth JUdicial Circuit was unable to attend and, pursuant to his suggestion, .Tudge Sim.ons was desig'nated by the Chief Justice to attend In his stead: Chief Judge William Denman of the ~lntll Judicial Circuit was unable to attend and, because of the pressure of tlle court business in the Circuit, be suggested no alternate for deSignation to attend in his stead. (231) 232 Hon. Marvin Jones, Chief Judge, United States Court of Claims; and Hon. Webster J. Oliver, Chief Judge, United States Customs Court, were in attendance for part of the session, and participated in the discussions relative to Retirement of Judges. Henry P. Chandler, DirectoOr; Elmore ''''bitehurst, Assistant Director; Will Shafroth, Chief, Division of Procedural Studies and Statistics; and Leland Tolman, Chief, Division of Business Ad ministration; all of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts, were in attendance throughout the session.l Paul L. -

THE VANPORT FLOOD and RACE RELATIONS in PORTLAND, OREGON Michael James Hamberg Central Washington University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at Central Washington University Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Spring 2017 FLOOD OF CHANGE: THE VANPORT FLOOD AND RACE RELATIONS IN PORTLAND, OREGON Michael James Hamberg Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Human Geography Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hamberg, Michael James, "FLOOD OF CHANGE: THE VANPORT FLOOD AND RACE RELATIONS IN PORTLAND, OREGON" (2017). All Master's Theses. 689. http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/689 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLOOD OF CHANGE: THE VANPORT FLOOD AND RACE RELATIONS IN PORTLAND, OREGON ___________________________ A Thesis Presented To The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University _____________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History ________________________________ by Michael James Hamberg June 2017 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Michael James Hamberg Candidate for the degree of Master -

Bank of America Chicago Marathon 1 Sunday, October 13, 2019 Media Course Record Progressions

Media Table of contents Media ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Media information ............................................................................................................................................................................4 Race week schedule of events ..................................................................................................................................................7 Quick facts ............................................................................................................................................................................................9 By the numbers ..................................................................................................................................................................................10 Top storylines ......................................................................................................................................................................................11 Bank of America Chicago Marathon prize purse ...........................................................................................................13 Time bonuses ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Participant demographics ............................................................................................................................................................15 -

The Strategic Elevation of District Court Judges to the Courts of Appeals

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2012 Elevating Justice: The Strategic Elevation of District Court Judges to the Courts of Appeals Mikel Aaron Norris [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Norris, Mikel Aaron, "Elevating Justice: The Strategic Elevation of District Court Judges to the Courts of Appeals. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1332 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Mikel Aaron Norris entitled "Elevating Justice: The Strategic Elevation of District Court Judges to the Courts of Appeals." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. John M. Scheb, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Nathan J. Kelly, Anthony J. Nownes, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Elevating Justice: The Strategic Elevation of District Court Judges to the Courts of Appeals A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Tennessee, Knoxville Mikel Aaron Norris May, 2012 Copyright © Mikel A. -

Council and Participants

THE AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE OFFICERS Cliairman of the Council GEORGE WHARTON PEl'l'ER P1'esiclcnt HARRISON TWEED 1st Vlcc-Presiclcnt WILLIAI\I A. SCHNADER 211cl Vicc-Pre1:1iclent JOHN G. BUCHANAN Treasurer BERNARD G. SEGAL Director HERBERT F. GOODRICII COUNCIL (April, 1959) Dillon Anderson ·---·····Houston ···--·-·-·--TC'xas Francis M. Bird ----·----Atlanta -···-··-···-Georgia John G. Buchanan ··-·--·Pittsburgh ···-···-·Pennsylvania Charles Bunn ---·····-··l\Iadison ····-·····-·Wiscousin Howard F. Burns ·----··-Cleveland ···-····-··Ohio Herbert W. Clark ···-···-San Francir.co ...... Califomia Homer D. Crotty ···----·Los Angeles ···-··-·CaHfornia R. Ammi Cutter ..... ----Boston .. ·-·-_ ··--·. l\fassuchusctts Norris Darrell ···-·-·---·New York -····-----New York Edward J. Dimock -----•.New York --·······-NewYork Arthur Dixon ... -------· Chicago ....·-· •••• -Illinois James Alger Fee -·---··-San Francisco ·-----California Gerald F. Flood ·-------·-Philadelphia --····--Pennsylvania Erwin N. Griswold -·-···Cambridge -··-------Massachusl•tts. H. Eastman Hackney •••. Pittsburgh --·-·-···Pennsylvania Learned Hand ······----·New York ---------·NewYork 1 Hcstatcmcnt or Trusts 2d V REPORTER AUSTIN W. SCOTT, Law School of Harvard University, Cambridge, l\fossachus etts ADVISERS RALPH J. BAKER, Law School of Harvm·d University, Cambridge, l\fossachusetts A. JAMES CASNER, Law School of Harvard University, Cambridge, l\fassaehusetts BERNARD HELLRING, Newark, New Jersey I. RUSSELL DENISON NILES, New York University School of Law, New York, New York JOHN V. SPALDING, Boston, Massachusetts DANIEL G. TENNEY, Jr., New York, New York WARREN A. SEAVEY, Law School of Harvard University, Cam- bridge, Massachusetts RAY.MONO S. WILKINS, Boston, Massachusetts Ex OFFICIO HARRISON TWEED, New York, New York President, The Ameri'canl,aw lm1tit11le HERBERT F. GOODRICH, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Dfrector, The American Law Institute • 1 Restatement or Trm1ts 2d III THE AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE COUNCIL (April, 1959)-Continued Albert J. -

Frank Bauman, 2009 USDCHS Oral History

FRANK A. BAUMAN November 21, 2005 Tape 1, Side 1 Portland, Oregon Foundational Years, 1921-1935 KS: This is Karen Saul speaking. I am a volunteer with the United States District Court Historical Society, and we are taking the oral history of Frank Anthony Bauman, Jr. This is November 21, 2005. We are in Mr. Bauman’s office at the Carriage House in Portland, Oregon, and this is the first tape and the first side. So, Mr. Bauman, would you begin by stating your full name, your date and place of birth? FB: Gladly, Miss Saul. Frank Anthony Bauman, Jr., and I was born in Portland, Oregon on June 10, 1921. KS: Mr. Bauman, I’d like to begin by having you tell me whatever you would like about your family history and your grandmother and grandfather. FB: Thank you. Let me begin with reference to my grandparents. I’ll take my paternal side first. My grandfather John Bauman, at that time spelt with two “Ns”, Baumann, was born in Berlin, Germany, and left Germany in approximately 1871 at the time of the Franco Prussian War. His reasons, I daresay, were twofold—one, political and two, as a young man he did not want to serve in a war to which he was not sympathetic. So he immigrated to America. Let me add that in 1977, I had the pleasure of being in Berlin for roughly one week when my son, Todd, was studying at the Free Berlin University, and I made an attempt to learn something about my grandfather through official records in Berlin. -

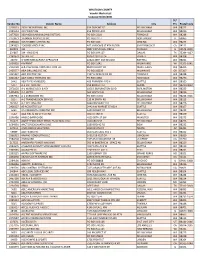

Vendor Number List (PDF)

WHATCOM COUNTY Vendor Master List Updated 06/26/2021 St/ Vendor No. Vendor Name Address City Prv Postal Code 2226513 2020 ENGINEERING INC 814 DUPONT ST BELLINGHAM WA 98225 2231654 24/7 PAINTING 256 PRINCE AVE BELLINGHAM WA 98226 2477603 360 MODULAR BUILDING SYSTEMS PO BOX 3218 FERNDALE WA 98248 2279973 3BRANCH PRODUCTS INC PO BOX 2217 NORTHBOOK IL 60065 2398518 3CS TIMBER CUTTING INC PO BOX 666 DEMING WA 98244 2243823 3DEGREE GROUP INC 407 SANSOME ST 4TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO CA 94111 294045 3M 2807 PAYSPHERE CIRCLE CHICAGO IL 60674-0000 234667 3M - XWD3349 PO BOX 844127 DALLAS TX 75284-4127 2161879 3S FIRE LLC 4916 123RD ST SE EVERETT WA 98208 24070 3-WIRE RESTAURANT APPLIANCE 22322 20TH AVE SE #150 BOTHELL WA 98021 1609820 4IMPRINT PO BOX 1641 MILWAUKEE WI 53201-1641 2319728 A & V GENERAL CONSTRUCTION LLC 8630 TILBURY RD MAPLE FALLS WA 98266 2435577 A&A DRILLING SVC INC PO BOX 68239 MILWAUKIE OR 97267 2431437 A&E ELECTRIC INC 2197 ALDERGROVE RD FERNDALE WA 98248 1816247 A&R CABLE THINNING INC PO BOX 4338 NOOKSACK WA 98276 5442 A&V TAPE HANDLERS 405 FAIRVIEW AVE N SEATTLE WA 98109 5477 A-1 GUTTERS INC 250 BOBLETT ST BLAINE WA 98230-4002 2378120 A-1 MOBILE LOCK & KEY 1956 S BURLINGTON BLVD BURLINGTON WA 98233 1405405 A-1 SEPTIC 565 WILTSE LN BELLINGHAM WA 98226 2457944 A-1 SHREDDING INC PO BOX 31366 BELLINGHAM WA 98228-3366 5514 A-1 TRANSMISSION SERVICE 210 W SMITH RD BELLINGHAM WA 98225 162561 A-1 WELDING INC 4000 IRONGATE RD BELLINGHAM WA 98226 2406127 A3 ACOUSTICS LLP 2442 NW MARKET ST #614 SEATTLE WA 98107 6461 AA ANDERSON COMPANY INC -

The Vanport Flood and Race Relations in Portland, Oregon

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Spring 2017 Flood of Change: the Vanport Flood and Race Relations in Portland, Oregon Michael James Hamberg Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Human Geography Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hamberg, Michael James, "Flood of Change: the Vanport Flood and Race Relations in Portland, Oregon" (2017). All Master's Theses. 689. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/689 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLOOD OF CHANGE: THE VANPORT FLOOD AND RACE RELATIONS IN PORTLAND, OREGON ___________________________ A Thesis Presented To The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University _____________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History ________________________________ by Michael James Hamberg June 2017 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Michael James Hamberg Candidate for the degree of Master of Arts APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY _________ ________________________________ Dr. Stephen Moore, Committee Chair _________ _________________________________ Dr. Daniel Herman _________ __________________________________ Dr. Brian Carroll _________ ___________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii Abstract FLOOD OF CHANGE: THE VANPORT FLOOD AND RACE RELATIONS IN PORTLAND, OREGON by Michael James Hamberg June 2017 This thesis examines race relations amid dramatic social changes caused by the migration of African Americans and other Southerners into Portland, Oregon during World War II. -

To the Power of OCF 2018 ANNUAL REPORT

You To the Power of OCF 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 1 OUR MISSION To improve lives for all Oregonians through the power of philanthropy. OUR VISION A healthy, thriving, sustainable Oregon. STRATEGIC PLAN 2019 Inspire Advance Engage Giving Opportunity Communities OUR VALUES COLLABORATIVE WISE STEWARDSHIP ACTION EQUITY, DIVERSITY SPIRIT OF AND INCLUSION COMMUNITY 2 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD 2 OCF’S IMPACT IN 2018 5 OUR REGIONS 6 RESILIENT LANDSCAPES, RESILIENT COMMUNITIES 38 PACIFIC NORTHWEST INITIATIVE 40 GO KIDS 41 RESEARCH 42 LATINO PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM 43 ARTS 44 ADVANCING BLACK STUDENT SUCCESS 45 GRANTS AND SCHOLARSHIPS 46 IN SERVICE TO YOU 47 OCF FUND LIST 48 INVESTMENT PROGRAM 62 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 63 STAFF 64 World music globe painting, Arts in Education of the Gorge. Programs funded by the OCF Studio to School initiative (see page 44). 3 Message From the Board RESEARCH TELLS US THAT BY LIFTING LOCAL VOICES FROM WITHIN COMMUNITIES WE CAN DELIVER SOLUTIONS THAT WORK. Dear Friends of OCF, We celebrate philanthropy. Our community make positive, transformative change across depends on our generosity. Built upon a foundation communities in Oregon. of shared values, together we can do great things Throughout the pages of this report, you’ll see for Oregonians. generosity, passion, commitment and optimism These shared values inform a bold new strategic as we deploy philanthropic resources and scale plan and visual identity to focus and amplify our strategies across communities. We can create work. By inspiring impactful giving that advances real impact when we work together to transform opportunities and engages communities in individual priorities into sustained community- addressing some of the most pressing challenges driven solutions. -

ALEXANDERS Ijiwrence

PAGE THREE ' EiGUT PAGES DAILY EAST OREGONIAN, PENDLETON, OREGON, MONDAY, JUNE 4, 1917. iiniiiniiiiuiinMMiuniiiiiHMniiiiiniunniiiMiHHiiiuniMiHnuMMMiMniiiinniir: HERIL1ISTQN CREAMERY IS BEING IMPROVED MONDAY. JUNK 4, 1017. Co. Whei war Is o'er, he's Dean Tatom fMiwnrd. MiHxUan KUUvrn. the troubled KI.FX.'-TItI- The no more. C KMKXT I1XKIK l I f AND "Thin wiuad march straight for l While I've four years to do this In, MOTOR IKT.I.Il-:- ward,' IX KACTOKV. FOR BUSINESS WEAR. 5 Sergeant Stelwer bellows, I'll tell you my lot in a short space 688 We find eay mo to do. of time Phone it By Mrs. II. Newell, IfOHtem at Two in one of the For we're tttralKhtforward fellows.!' relutiiig this dally prayer of I. H. Blue Sere mine. Attractive Fartira; Mr. and Mr. things never goes out M. Konunnrer Home from Wcddln that A Xature Fakci of style; it's always neat ' Now I lay me dowri to sleep, Trl. , "W. T. Rlesninjc of Her mist on la always appro- CHEESE I pray the I,ord my soul to keep, and dressy; laying the foundation of a fine dairy (Ka Oregon ian Special.) priate ; always satisfac- 3 aay cornrry correspond- Grant th 't no other sailor take Her-n-lst- Limburjrer in Bricks 30 herd," a My HERMI8TON, June 1. The is provided ent. He be some bird. shoes or socks before I wake. Creamery Company ia making tory. That mut my slum- Tins - 20 And, Lord, please protect some Improvement to a good piece of Blue In ber, much needed it's - Were You Ono of Them. -

Robert Belloni: an Oral History

Robert Belloni: An Oral History i ii Robert Belloni An Oral History FOREWORD BY JUDGE OWEN PANNER US District Court of Oregon Historical Society Oral History Project Portland, Oregon iii Copyright © 2011 United States District Court of Oregon Historical Society Printed in the United States of America PROJECT STAFF Janice Dilg, Oral History Liaison Adair Law, Editor & Page layout Jim Strassmaier, Interviewer iv CONTENTS Foreword....................................................................................................................................xx Introduction..............................................................................................................................xx Tape One, September 19, 1988.................................................................................................1 Side 1—Family History, Parents Side 2—Family Status, School Tape Two, September 19, 1988...............................................................................................14 Side 1—Influence of Adults, Educational Plans Side 2—Father’s Death, Early Political Memories Tape Three, September 28, 1988............................................................................................24 Side 1—Work After College, Military Service, Philippine Islands and Japan Side 2—Marriage and Law School, Memories of Ted Goodwin Tape Four, September 28, 1988 - November 7, 1988...........................................................34 Side 1—Inspiring Teachers Side 2—Early Days as a Lawyer, Early Political Office Tape