Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marianne Dashwood and Charlotte Lucas (The Christian Ideal of Marriage in Jane Austen)

Not Said But Shown 432 17. Marianne Dashwood and Charlotte Lucas (The Christian Ideal of Marriage in Jane Austen) ----- Marianne Dashwood at seventeen believes in “wholeheartedness.” One should cultivate right feelings as far as one possibly can, and express them frankly and to the full; and all with whom one can relate properly must do the same. One’s feelings should be intense, and the expression of them should be enthusiastic and eloquent. Towards those whose feelings are right, but who cannot achieve this freedom of expression, one must be charitable; but one should avoid all whose thought and behavior is governed by convention. Following convention corrupts one’s “sensibility,” so that one can no longer tell what the truth of natural feeling is. Thus, when Edward Ferrars and Marianne’s sister Elinor become mutually attached, Marianne approves of Edward — and she certainly agrees with her mother, who says, “I have never yet known what it was to separate esteem and love” (SS, I, iii, 16). But she cannot imagine how Elinor can be in love with Edward, because he lacks true “sensibility.” “Edward is very amiable, and I love him tenderly. But . his figure is not striking . His eyes want all that spirit, that fire, which at once announce virtue and intelligence . he has no real taste . I could not be happy with a man whose taste did not in every point coincide with my own . how spiritless, how tame was Edward’s manner in reading to us last night! . it would have broke my heart had I loved him, to hear him read with so little sensibility” (17-8). -

Sense and Sensibility by Kate Hamill Based on the Novel by Jane Austen

SENSE AND SENSIBILITY BY KATE HAMILL BASED ON THE NOVEL BY JANE AUSTEN DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. SENSE AND SENSIBILITY Copyright © 2016, Kate Hamill, based on the novel by Jane Austen All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of SENSE AND SENSIBILITY is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for SENSE AND SENSIBILITY are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

December 11, 2012–January 13, 2013

December 11, 2012–January 13, 2013 SENSE AND SENSIBILITY Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents PLAY GUIDE • Written by Lindsey Schmeltzer Education Intern Melissa Neumann Education Intern • By Jane Austen Adapted for the stage by Mark Healy Play Guide edited by Directed by Art Manke Leda Hoffmann December 11, 2012-January 13, 2013 Education Coordinator Quadracci Powerhouse JC Clementz Literary Assistant MARK’S TAKE: “Sense and Sensibility is my favorite of Jenny Kostreva Education Director Jane Austen’s wonderful works. I love the relationship between the two sisters — Lisa Fulton their contrasts, their journeys, their growth Director of Marketing throughout—and how this 200-year-old story • still resonates. We all fall in love, we all have our hearts broken, we all go through periods Graphic Design by where our lives are suddenly turned upside- Eric Reda down, and Austen’s beautiful prose manages to get right to the heart of those moments and makes us feel and say, ‘wow, I know that, I felt that, I understand that.’” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3 Synopsis Page 4 The Characters Page 5 Character Relationships Tickets: 414-224-9490 Page 6 The Settings www.MilwaukeeRep.com Page 7 Jane Austen’s Biography Mark Clements Page 8 Historical Context: Artistic Director The Regency Era Dawn Helsing Wolters Page 9 Sense vs. Sensibility Managing Director Page 10 Adaptation: From Novel To Stage Milwaukee Repertory Theater 108 E. Wells Street Page 11 Glossary Milwaukee, WI • 53202 Page 12 Creating the Rep Production Page 14 Visiting The Rep SYNOPSIS Henry Dashwood has three children: a son, John, by his first wife and two daughters, Elinor and Marianne, by his second. -

Toolkit Sense & Sensibility Toolkit

Bedlam's TOOLKIT Welcome! This Toolkit introduces topics, content, themes, and more about the A.R.T. production of Bedlam’s Sense & Sensibility. This exhuberant and inventive take on a Jane Austen classic explores questions of balancing reputation, expectation, and love using humor, emotion, and bold theatricality. This Toolkit is designed for classroom and individual use as preparation for or follow-up to seeing the A.R.T. production of Bedlam’s Sense & Sensibility. In its pages you will find articles, activities, and tools that help to illuminate the background and ideas at play in the work on stage: the context of Jane Austen and her classic text, concepts of theatrical adaptation, Bedlam’s signature performance style, and more. See you at the theater! BRENNA NICELY JAMES MONTAÑO A.R.T. Education & Community A.R.T. Education & Community Programs Manager Programs Fellow BEDLAM’S SENSE & SENSIBILITY TOOLKIT 2 Table of Contents SENSE & SENSIBILITY: THE NOVEL Summary..........................................................................................................................5-6 The Characters...............................................................................................................7-8 The Script of Sensibility.............................................................................................9-11 The World of Sense & Sensibilty .........................................................................12-15 Sense in Adaptation...................................................................................................16-18 -

Sense and Sensibility by KATE HAMILL BASED on the NOVEL by JANE AUSTEN IMAGE by JAMES HARTLEY JAMES by IMAGE Study Guide

STATE THEATRE COMPANY SOUTH AUSTRALIA PRESENTS Sense and Sensibility BY KATE HAMILL BASED ON THE NOVEL BY JANE AUSTEN IMAGE BY JAMES HARTLEY JAMES BY IMAGE Study Guide COMPILED BY HANNAH MCCARTHY-OLIVER *PLEASE USE IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE PRE PRODUCTION BRIEFING Marianne – What has wealth or fame to do with being happy? Elinor – Wealth has much to do with it. Marianne – Elinor, for shame! Suitable for Years 9-12 4 May - 26 May 2018 Dunstan Playhouse Running Time – Approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes – Including Interval Synopsis Set in the gossip filled world of late 18th century England, Hamill’s Sense and Sensibility is an entertaining, fun, frivolous and heart warming adaptation of Jane Austen’s well known novel. It tells the story of the Dashwood family, with the focus on hyper sensitive Marianne and the ever sensible Elinor. The show opens as a group of gossips discuss the death of the Dashwood patriarch. With limited financial means and reduced social standing the Dashwoods find themselves in a troubling situation for a family of women during the Regency period. The only way to rectify their issues… find husbands! Character Descriptions Elinor Dashwood – the eldest Dashwood sister; sensible Marianne Dashwood – the middle Dashwood sister; sensitive Margaret Dashwood – the youngest Dashwood sister; 10-13 years old Mrs Dashwood – mother to the Dashwood sisters John Dashwood – half brother to the Dashwood sisters (from their father’s side; no blood relation to Mrs Dashwood) Edward Ferrars – a gentleman; a bachelor Fanny (Ferrars) Dashwood -

1 Deborah Mondadori Simionato the Many Journeys in Jane Austen's Persuasion

DEBORAH MONDADORI SIMIONATO THE MANY JOURNEYS IN JANE AUSTEN’S PERSUASION: SOCIAL, GEOGRAPHICAL AND EMOTIONAL CROSSINGS PORTO ALEGRE 2016 1 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS ÁREA DE ESTUDOS DE LITERATURA LINHA DE PESQUISA: SOCIEDADE, (INTER)TEXTOS LITERÁRIOS E TRADUÇÃO NAS LITERATURAS ESTRANGEIRAS MODERNAS THE MANY JOURNEYS IN JANE AUSTEN’S PERSUASION: SOCIAL, GEOGRAPHICAL AND EMOTIONAL CROSSINGS AUTORA: DEBORAH MONDADORI SIMIONATO ORIENTADORA: SANDRA SIRANGELO MAGGIO Dissertação de mestrado em Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre. Porto Alegre, Março, 2016. 2 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA SIMIONATO, Deborah Mondadori The Many Journeys in Jane Austen’s Persuasion: Social, Geographical and Emotional Crossings. Deborah Mondadori Simionato Porto Alegre: UFRGS, Instituto de Letras, 2016. 141 p. Dissertação (Mestrado - Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras) Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. 1. Literatura inglesa. 2. Jane Austen. 3. Persuasão. 4. Jornadas. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Living my dreams is only possible due to the unwavering support of my parents, without whom I would not be here today, so I would like to start by thanking them. Dad, I want to thank you for always believing in me, and assuring me I could do whatever I wished – as long as I read. Maybe someday I will work in the family business, but for now, I will just keep on reading. Mum, you are my Wonder Woman, and nothing I might try to say about you and your never-ending love will do you justice, so I will just thank you for everything, always. -

Sense and Sensibility Adapted for the Stage from Jane Austen's Novel by Joseph Hanreddy and JR Sullivan

Sacramento Theatre Company Study Guide Sense and Sensibility Adapted for the stage from Jane Austen's novel by Joseph Hanreddy and JR Sullivan Study Guide Prepared: August 25, 2015 by William Myers Additional Contributor: Romyl Mabanta 1 Sacramento Theatre Company Mission Statement The Sacramento Theatre Company (STC) strives to be the leader in integrating professional theatre with theatre arts education. STC produces engaging professional theatre, provides exceptional theatre training, and uses theatre as a tool for educational engagement. Our History The theatre was originally formed as the Sacramento Civic Repertory Theatre in 1942, an ad hoc troupe formed to entertain locally-stationed troops during World War II. On October 18, 1949, the Sacramento Civic Repertory Theatre acquired a space of its own with the opening of the Eaglet Theatre, named in honor of the Eagle, a Gold Rush-era theatre built largely of canvas that had stood on the city’s riverfront in the 1850s. The Eaglet Theatre eventually became the Main Stage of the not-for-profit Sacramento Theatre Company, which evolved from a community theatre to professional theatre company in the 1980s. Now producing shows in three performance spaces, it is the oldest theatre company in Sacramento. After five decades of use, the Main Stage was renovated as part of the H Street Theatre Complex Project. Features now include an expanded and modernized lobby and a Cabaret Stage for special performances. The facility also added expanded dressing rooms, laundry capabilities, and other equipment allowing the transformation of these performance spaces, used nine months of the year by STC, into backstage and administration places for three months each summer to be used by California Musical Theatre for Music Circus. -

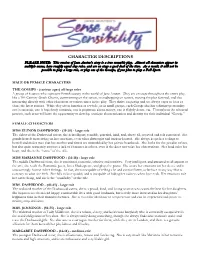

Character Descriptions

CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS PLEASE NOTE: This version of Jane Austen’s story is a true ensemble play. Almost all characters appear in multiple scenes, have roughly equal size roles, and are on stage a good deal of the time. As a result, it will not be possible to play a large role, or play one of the Gossips, if you plan to play a Fall Sport. MALE OR FEMALE CHARACTERS THE GOSSIPS - (various ages) all large roles A group of 6 actors who represent British society in the world of Jane Austen. They are on stage throughout the entire play, like a 19th Century Greek Chorus, commenting on the action, eavesdropping on scenes, moving the plot forward, and also interacting directly with other characters at various times in the play. They thrive on gossip and are always eager to hear or share the latest rumors. While they often function as a whole, or in small groups, each Gossip also has a distinct personality -- one is sarcastic, one is hopelessly romantic, one is pragmatic about money, one is slightly dense, etc. Throughout the rehearsal process, each actor will have the opportunity to develop a unique characterization and identity for their individual “Gossip.” FEMALE CHARACTERS MISS ELINOR DASHWOOD - (19-20) - large role The eldest of the Dashwood sisters, she is intelligent, sensible, practical, kind, and, above all, reserved and self-contained. She guards herself from acting on her emotions, even when distraught and broken-hearted. She always keeps her feelings to herself and makes sure that her mother and sisters are untroubled by her private heartbreak. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Renáta Vašaničová The Role of Women, Marriage, Courtship and Social Status in the selected works of Jane Austen Postavení žen, manželství, dvoření a sociální status ve vybraných dílech Jane Austen Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Libor Práger OLOMOUC 2012 1 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a použila pouze literaturu uvedenou v přiloženém seznamu. Nemám námitek proti půjčení práce se souhlasem katedry ani proti zveřejnění práce nebo její části. V Olomouci dne 31. 12. 2011 ____________________________ vlastnoruční podpis 2 Děkuji PhDr. Liborovi Prágrovi za odborné vedení mé bakalářské diplomové práce, za poskytnuté konzultace a rady a za laskavé zapůjčení materiálů k této práci. 3 Abstract Surname and first name: Vašaničová Renáta Name of the department: The Department of English and American studies, Philosophical Faculty Name of the bachelor´s thesis: The Role of Women, Marriage, Courtship And Social Status in the selected works of Jane Austen Consultant : PhDr. Libor Práger Key words: social status, middling sort, middle class, sense, sensibility, pride, prejudice, women, courtship, marriage, fashion, household, role, men Description of the bachelor´s thesis: The bachelor´s thesis is focused on the selected works of Jane Austen – Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. The work is describing the position of women from the middle class, the analysis of the courtship, marriage and social status of women in the Regency Era. The description of the historical background is the necessary key point to understand the work – how the historical events were influencing the era when Jane Austen lived. -

Unlocking the Rape: an Analysis of Austen's Use of Pope's Symbolism

Unlocking the Rape: An Analysis t of Austen’s Use of :L Pope’s Symbolism i in Sense and Sensibility CATHERINE BRISTOW Catherine Bristow lives in Philadelphia, where she writes and teaches adult education for the Women’s Association for Women’s Alternatives. Early in the story of Sense and Sensibility, Marianne Dashwood allows her beloved Willoughby to “cut off a long lock of her hair” (60), as a younger sister later reports. At least one critic has noticed “the oblique contrast between Marianne … and Pope’s painted Belinda” (Sulloway 45), including the repetition of the word “lock” twice during sister Margaret’s retelling (60). An analysis of Sense and Sensibility in light of the text of “The Rape of the Lock” reveals that Austen appro- priates symbols, scenes, and characters from the poem with great reg- ularity. Where Austen’s message differs from Pope’s is in presenting the goal of restraint. Austen is less concerned for the general good of society than for the safety of each individual woman. The regulation of passion is, for her, a practice best recommended to women to help them avoid the “dementia and decay of the wronged woman,” as Claudia Johnson puts it (160). Marianne Dashwood and Pope’s Belinda are young, marriageable girls consumed by “ruling passions,” which at first glance appear to be nearly opposite. Belinda’s desire is for power over the male sex and unlimited opportunity to exercise her coquettishness. Pope describes her “shining Ringlets” (ii.22), which aim at “the Destruction of Mankind” (ii.19); she “Burns to encounter” (iii.26) potential “Slaves” (ii.23). -

Strong Female Characters: Jane Austen's Vs

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 4-30-2018 Strong Female Characters: Jane Austen's vs. The Mashups' Rachel McCoy Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation McCoy, Rachel, "Strong Female Characters: Jane Austen's vs. The ashM ups'" (2018). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 740. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/740 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRONG FEMALE CHARACTERS: JANE AUSTEN’S VS. THE MASHUPS’ A Capstone Experience/ Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of English Literature with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Rachel T. McCoy ***** Western Kentucky University 2018 CE/T Committee: Professor Walker Rutledge, Chair Professor Robert Hale Doctor Christopher Keller Copyright by Rachel McCoy 2018 ABSTRACT The comparison of Strong Female Characters in Jane Austen’s novels Pride & Prejudice and Sense & Sensibility, with the altered characters in the monster mashups by Seth Grahame-Smith and Ben Winters, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters, respectively, reveals differences between the two society’s understanding and portrayal of strength and femininity. Because these texts are so closely connected – Austen is listed as a co-author of both mashups – the differences evident in the representations of women more clearly reveal the differing cultural values. -

Hale Center Theater Orem Proudly Presents

HALE CENTER THEATER OREM PROUDLY PRESENTS Original Direction by: Dr. Christopher Clark STARRING Malia MacKay Scout Smith Lisa Zimmerman SUPPORTING Rachel Bigler Alyssa Buckner Bryan Dayley Dianna Graham Will Ingram Jon Liddiard Jordan Mazzocato Annadee Morgan Cleveland McKay Nicoll Julie Suazo FEATURING Yana Andersen Emma Eugenia Belnap Justin Bills Woody Brook Calee Gardner Erica Glenn Jeff Thompson Anya Wilson Director Production Manager & Master Carpenter Blake Barlow Lighting Design Bobby Swenson Joseph Governale Based on Direction by Costume Director Dr. Christopher Clark Costume Design Anne Swenson Janet Swenson Production Stage Manager Hair & Makeup Director Meagan M. Downey Set Design, Technical Melinda Wilks Direction, & Sound Design Dialect Coach Cole McClure Technicians Dianna Graham Ryan Fallis & Richie Trimble Hair & Makeup Design Choreography Savanna Waldron Cutter / Draper Jennifer Hill-Barlow Jessica Barksdale Properties Linda Hale Assistant Properties Cody Hale Sense & Sensibility 3 Check out Twitter our social Pinterest media sites. Facebook Instagram YouTube also visit us at haletheater.org search #hcto 4 Hale Center Theater Orem CAST OF CHARACTERS ELINOR DASHWOOD ....................................Lisa Zimmerman (MWF ) Malia Mackay (TTHS) u/s Erica Glenn MARIANNE DASHWOOD ....................................................................... Scout Smith (M-S) u/s Calee Gardner MRS. DASHWOOD / ANNE STeeLE / GOSSIP ......................................Annadee Morgan (MWF) Dianna Graham (TTHS)