East of the Saser La Harish Kapadia 28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final BLO,2012-13

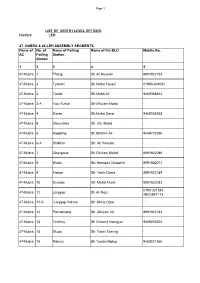

Page 1 LIST OF BOOTH LEVEL OFFICER . District: LEH 47- NUBRA & 48-LEH ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS. Name of No. of Name of Polling Name of the BLO Mobile.No. AC Polling Station Station 1 3 3 4 5 47-Nubra 1 Thang Sh.Ali Hussain 8991922153 47-Nubra 2 Tyakshi Sh.Mohd Yousuf 01980-248031 47-Nubra 3 Turtuk Sh.Mohd Ali 9469368812 47-Nubra 3-A Youl Turtuk Sh:Ghulam Mohd - 47-Nubra 4 Garari Sh.Mohd Omar 9469265938 47-Nubra 5 Chulunkha Sh: Gh. Mohd - 47-Nubra 6 Bogdang Sh.Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 47-Nubra 6-A Shilkhor Sh: Ali Hassain - 47-Nubra 7 Changmar Sh.Ghulam Mehdi 8991922086 47-Nubra 8 Waris Sh: Namgail Chosphel 8991922073 47-Nubra 9 Fastan Sh: Tashi Dawa 8991922149 47-Nubra 10 Sunudo Sh: Mohd Anvar 8991922082 0190-221344 47-Nubra 11 Largyap Sh Ali Rozi /9622957173 47-Nubra 11-A Largyap Yokma Sh: Nima Otzer - 47-Nubra 12 Pachathang Sh. Ghulam Ali 8991922182 47-Nubra 13 Terchey Sh Chemet Namgyal 9469266204 47-Nubra 14 Skuru Sh; Tashi Tsering - 47-Nubra 15 Rakuru Sh Tsetan Motup 9469221366 Page 2 47-Nubra 16 Udamaru Sh:Mohd Ali 8991922151 47-Nubra 16-A Shukur Sh: Sonam Tashi - 47-Nubra 17 Hunderi Sh: Tashi Nurbu 8991922110 47-Nubra 18 Hunder Sh Ghulam Hussain 9469177470 47-Nubra 19 Hundar Dok Sh Phunchok Angchok 9469221358 47-Nubra 20 Skampuk Sh: Lobzang Thokmed - 47-Nubra 21 Partapur Smt. Sari Bano - 47-Nubra 22 Diskit Sh: Tsering Stobdan 01980-220011 47-Nubra 23 Burma Sh Tuskor Tagais 8991922100 47-Nubra 24 Charasa Sh Tsewang Stobgais 9469190201 47-Nubra 25 Kuri Sh: Padma Gurmat 9419885156 47-Nubra 26 Murgi Thukje Zangpo 9419851148 47-Nubra 27 Tongsted -

(IRP) 2020 Week-9

IASbaba’s Integrated Revision Plan (IRP) 2020 Week-9 CURRENT AFFAIRS QUIZ Q.1) With reference to Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme, which of the statements given below is incorrect? a) It provides loans to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) only. b) It was rolled out as part of the Centre’s Aatmanirbhar package in response to the COVID•19 crisis. c) It has a corpus of ₹41,600 crore and provides fully guaranteed additional funding of up to ₹3 lakh crore. d) None Q.1) Solution (a) The Centre has expanded its credit guarantee scheme for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to cover loans given to larger firms, as well as to self•-employed people and professionals who have taken loans for business purposes. The Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme was rolled out in May as part of the Centre’s Aatmanirbhar package in response to the COVID•19 crisis. It has a corpus of ₹41,600 crore and provides fully guaranteed additional funding of up to ₹3 lakh crore. Source: https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/credit-guarantee-extended-to-larger- firms-self-employed/article32249835.ece Q.2) Which of the following statements about Bal Gangadhar Tilak is/are correct? 1. He founded the Fergusson College in Pune. 2. He was part of the extremist faction of Indian National Congress. 3. He was associated with the Hindu Mahasabha. Select the correct answer using code below a) 1 and 2 b) 2 only c) 1 and 3 only d) 1, 2 ad 3 Q.2) Solution (a) Bal Gangadhar Tilak IASbaba’s Integrated Revision Plan (IRP) 2020 Week-9 He was commonly known as Lokamanya Tilak. -

Approved Capex Budget 2020-21 Final

Capex Budget 2020-21 of Leh District I NDEX S. No Sector Page No. S. No Sector Page No. 1 2 3 1 2 3 GN-0 3 29 Forest 56 - 57 GN-1 4 - 5 30 Parks & Garden 58 1 Agriculture 6 - 9 31 Command Area Dev. 59 - 60 2 Animal Husbandry 10 - 13 32 Power 61 - 62 3 Fisheries 14 33 CA&PDS 63 - 64 4 Horticulture 15 - 16 34 Soil Conservation 65 5 Wildlife 17 35 Settlement 66 6 DIC 18 36 Govt. Polytechnic College 67 7 Handloom 19 - 20 37 Labour Welfare 68 8 Tourism 21 38 Public Works Department 9 Arts & Culture 22 1 Transport & Communication 69 - 85 10 ITI 23 2 Urban Development 86 - 87 11 Local Bodies 24 3 Housing Rental 88 12 Social Welfare 25 4 Non Functional Building 89 - 90 13 Evaluation & Statistics 26 5 PHE 97 - 92 14 District Motor Garages 27 6 Minor Irrigation 93 - 95 15 EJM Degree College 28 7 Flood Control 96 - 99 16 CCDF 29 8 Medium Irrigation 100 17 Employment 30 9 Mechanical Division 101 18 Information Technology 31 Rural Development Deptt. 19 Youth Services & Sports 32 1 Community Development 102 - 138 20 Non Conventional Energy 33 OTHERS 21 Sheep Husbandry 34 - 36 1 Untied 139 22 Information 37 2 IAY 139 23 Health 38 - 42 3 MGNREGA 139 24 Planning Mechinery 43 4 Rural Sanitation 139 25 Cooperatives 44 - 45 5 SSA 139 26 Handicraft 46 6 RMSA 139 27 Education 47 - 53 7 AIBP 139 28 ICDS 54 - 55 8 MsDP 139 CAPEX BUDGET 2020-21 OF LEH DISTRICT (statement GN 0) (Rs. -

The Following Staff Is Hereby Appointed for Conduct of Poll of Panchayat Elections-2018, Panchayat Halqa DISKIT Block DISKIT District LEH

APPOINTMENT ORDER OF THE POLLING STAFF The following staff is hereby appointed for conduct of poll of Panchayat Elections-2018, Panchayat Halqa DISKIT block DISKIT District LEH. Polling Station Number Name of the Presiding Officer Name of the Polling Officers and Name with complete with Designation,Posting with Designation,Posting particulars of its location Place,Department and Place,Department and Controlling Officer Controlling Officer 1 TSEWANG DORJAY 001 SAJAD ALI . SENIOR ASSISTANT GANGTAK MASTER PANAMIK HS CHUCHOT YOKMA RURAL DEVELOPMENT EDUCATION HSS GANGTAK ACD CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER 2 TSERING ANGCHUK . TEACHER M/S SKARA PartyCode : 10Party028 EDUCATION ZEO LEH 1 DORJAY NAMGAIL 002 JIGMET RABGAIS . DRAFTSMAN KHAMATONG STATISTICAL ASSISTANT PWD CIRCLE LEH LEH PWD ANIMAL HUSBANDARY HSS DISKIT SE PWD CHIEF ANIMAL HUSBANDRY OFFICER 2 SONAM NORBOO . TEACHER KENKAR SAKTI PartyCode : 10Party010 EDUCATION CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER 1 DORJAY NAMGIAL 003 TSEWANG RIGZEN . TEACHER GONPA PEM PS TSELO BHSS LEH EDUCATION EDUCATION HSS DISKIT ZEO NYOMA CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER 9469164299 2 ABI DIN . F.D. ASSTT SINDHU PartyCode : 10Party001 FISHRIES AD FISHRIES 1 SADATH ALI 004 TSERING WANGCHUK . SENIOR ASSISTANT SPAIR HEADMASTER CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICE LEH HS HESHUK EDUCATION EDUCATION HSS DISKIT CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER 2 TSERING ANGCHUK . OPERATOR MECH DIV LEH PartyCode : 10Party027 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING XENDEPARTMENT MECHANICAL 1 SONAM PUNCHOK 005 IFTIKHAR ALAM . TEACHER TSAKHING GONGMA MASTER HS STOK HS LIKIR EDUCATION EDUCATION HSS DISKIT CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER 9419981866 2 GHULAM MEHDI . WORK SUPERVISOR LEH PartyCode : 10Party015 PWD XEN RNB NIC J&K "Greater Participation for Stronger Democracy" Page 1 of 2 APPOINTMENT ORDER OF THE POLLING STAFF The following staff is hereby appointed for conduct of poll of Panchayat Elections-2018, Panchayat Halqa DISKIT block DISKIT District LEH. -

2000 Ladakh and Zanskar-The Land of Passes

1 LADAKH AND ZANSKAR -THE LAND OF PASSES The great mountains are quick to kill or maim when mistakes are made. Surely, a safe descent is as much a part of the climb as “getting to the top”. Dead men are successful only when they have given their lives for others. Kenneth Mason, Abode of Snow (p. 289) The remote and isolated region of Ladakh lies in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, marking the western limit of the spread of Tibetan culture. Before it became a part of India in the 1834, when the rulers of Jammu brought it under their control, Ladakh was an independent kingdom closely linked with Tibet, its strong Buddhist culture and its various gompas (monasteries) such as Lamayuru, Alchi and Thiksey a living testimony to this fact. One of the most prominent monuments is the towering palace in Leh, built by the Ladakhi ruler, Singe Namgyal (c. 1570 to 1642). Ladakh’s inhospitable terrain has seen enough traders, missionaries and invading armies to justify the Ladakhi saying: “The land is so barren and the passes are so high that only the best of friends or worst of enemies would want to visit us.” The elevation of Ladakh gives it an extreme climate; burning heat by day and freezing cold at night. Due to the rarefied atmosphere, the sun’s rays heat the ground quickly, the dry air allowing for quick cooling, leading to sub-zero temperatures at night. Lying in the rain- shadow of the Great Himalaya, this arid, bare region receives scanty rainfall, and its primary source of water is the winter snowfall. -

International Relations | Topic: Effect of Policies and Politics of Developed & Developing Countries on India's Interests

Page 1 Battle for Hong Kong2 A phantom called the Line of Actual Control3 G7 outdated, says Trump, invites India, Russia and others to September meeting6 India, China bring in heavy equipment and weaponry to their rear bases near eastern Ladakh8 India, China and fortifying the Africa outreach10 Shoring up Indo-Pacific13 It's time to play hardball with China over its misadventures15 Wolf Warrior Diplomacy17 Move over G7, it's time for a new and improved G1119 Seven to eleven: The Hindu Editorial on India and G-721 The Delhi-DC-Beijing triangle - editorials - Hindustan Times23 India-Australia meet strengthens ties25 The de-escalation road map for India and China27 A chill in U.S.-China relations29 Skyrocketing tensions: The Hindu Editorial on U.S.-China ties32 Eastern Ladakh standoff: Indian and Chinese armies hold Lt-General-level talks34 In Persian Gulf littoral, cooperative security is key36 Raja Mandala: It’s not about America40 Resume dialogue with Nepal now42 Pincer provocations?46 ‘China disregarding historic commitments on Naku La’49 An unravelling of the Group of Seven51 As Nepal paints itself into a corner on Kalapani issue, India must tread carefully55 A case for quiet diplomacy58 Back from the brink: The Hindu Editorial on India-China border row61 Black lives and the experiment called America63 India-China: the line of actual contest67 India slams Nepal for adopting a new map70 Forgotten in the fog of war, the last firing on the India-China border72 No longer special: The Hindu Editorial on India-Nepal ties74 ‘There will be no -

Page-1.Qxd (Page 2)

Excelsiordaily Vol No. 51 No. 260 JAMMU, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2015 REGD.NO.JK-71/15-17 16+4 (Magazine) = 20 Pages ` 4.00 RNI No. 28547/1992 HM to visit forward posts, fly over others Minor injured in firing succumbs Rajnath to hold high level security Hizb militant found dead Adil Lateef recharge his phone from a near- Witnesses said when the by shop. Though the duo was body of Burhan reached his review along China LAC for 3 days SRINAGAR, Sept 19: A rushed to hospital but Bashir ancestral village, a pale of Sanjeev Pargal Commanders, civil and police over Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO), three year old kid who was succumbed to injuries enroute gloom descended in entire administration in Leh and the Track Junction, Murgo and injured yesterday during an while Burhan was shifted to area and people staged mas- JAMMU, Sept 19: Union troops during his visit to for- Burtse BOPs to have aerial view attack on his father, a former Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of sive protests. The women were Home Minister Rajnath Singh ward posts along the China bor- of LAC position. These BOPs Jamiat-ul-Mujahideen mili- Medical Sciences (SKIMS) seen wailing and beating their will hold high level review of der. He will assess requirements either don't have direct road tant, by gunmen in north Soura where he lost his life chests. The witnesses said, security scenario along with of the ITBP jawans, who have access from Leh or were located Kashmir’s Sopore area of today early morning. hundreds of people attended top Commanders of Indo- been manning LAC along with in very far off areas. -

Marches Et Frontières Dans Les Himalayas

C h a P i t r e 1 les HimalaYas et la barrière Une union très imparfaite 1. LES HIMALAYAS oU la PÉriPHÉrie COMME QUESTION ceNTRALE entre la plaine indo-gangétique et les basses terres du Takla Makan-Gobi sont concentrées 96 % des terres de plus de 3 000 m de l’asie1, qui constituent le plus formidable ensemble de hautes terres du globe (d’une altitude moyenne de 4 500 m), circonscrit au nord et au sud par des chaînes culminant à 7 000 m, voire 8 000 m . Étroitement liées entre elles au sortir du nœud des Pamirs (500 km à peine séparent Karghalik de Rawalpindi), les chaînes divergent et s’individualisent rapidement pour composer de longs aligne- ments globalement orientés ouest-est (la largeur de l’ensemble est alors de 1 . asie insulaire non comprise . Le chiffre associe au Tibet les massifs périphériques qui forment avec lui un ensemble continu . Voir André Cailleux, « Tibet, Andes : catastrophes, plaques et rétroaction », Annales de géographie, no 488, juillet-août 1979, p . 419-431 . 20 Marches et frontières dans les Himalayas près de 1 500 km) avant de se réunir au rebroussement birman et d’épouser une direction méridienne (quelque 1 300 km de largeur) . Dans ce contexte régional l’Himalaya apparaît comme « un monde à part, indien par sa base, par sa végétation, par son climat, par les fleuves qui s’y épanchent, tibétain par l’énorme protubérance terrestre dont il forme le rebord méridional2 » . il est « la figure géographique qui domine l’inde3 » et, dans la géographie régionale classique, l’une des trois macro-régions de l’inde, avec les Plaines septentrionales (Northern plains) et la péninsule du Deccan . -

Mountains & Monasteries of Northern India

MOUNTAINS & MONASTERIES OF NORTHERN INDIA Detailed Itinerary Ladakh, Dharamsala and the Golden Temple Aug 14/19 Experience a more remote, serene and spiritual Facts & Highlights India! See snowcapped Himalayan peaks as you • 22 land days • Maximum 16 travelers • Start and finish in traverse the world’s highest pass. Visit the holy Delhi • All meals included • Includes 1 internal flight Sikh Golden Temple. Savor the local culture of • Sightseeing of Delhi • Enjoy Ladakh and the Himalayas • Visit Shey, Thikse and Hemis Monasteries • See the a home stay in a beautiful Himalayan valley 900-year-old murals of Alchi • Travel over the world’s and feel enlightened as you encounter Tibetan highest pass • Experience a local home-stay in the foothills of the Himalayas • Travel to Dharamsala, home of the Buddhist monks, culture, monasteries and chants Tibetan Government in exile • Visit the Dalai Lama that echo through the mountains and valleys. monasteries • Visit the Golden Temple in Amritsar • Attend the colorful Hemis Festival in Leh We begin in Delhi, the capital of India, before taking a fast train to Amritsar where we visit the Departure Dates & Price Golden Temple. The Golden Temple glitters with Jun 16 - Jul 07, 2020 - $5495 USD gold and marble and is one of the holiest Sikh Activity Level: 2 shrines. Afterwards we drive up into the foothills Comfort Level: 8 days over 9,000 feet. Some rough, dusty roads and long drives.. of the Himalayas stopping at the 6th century Accommodations Comfortable hotels/ town of Chamba. Experience a 3-night home stay guesthouses with private bathroom facilities. -

Volume 27 # June 2013

THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER Volume 27 l June 2013 Contents Annual Seminar February 2013 ........................................ 2 First Jagdish Nanavati Awards ......................................... 7 Banff Film Festival ................................................................. 10 Remembrance George Lowe ....................................................................................... 11 Dick Isherwood .................................................................................... 3 Major Expeditions to the Indian Himalaya in 2012 ......... 14 Himalayan Club Committee for the Year 2013-14 ........... 28 Select Contents of The Himalayan Journal, Vol. 68 ....... 30 THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER The Himalayan Club Annual Seminar 2013 The Himalayan Club Annual Seminar, 03 was held on February 6 & 7. It was yet another exciting Annual Seminar held at the Air India Auditorium, Nariman Point Mumbai. The seminar was kicked off on 6 February 03 – with the Kaivan Mistry Memorial Lecture by Pat Morrow on his ‘Quest for the Seven and a Half Summits’. As another first the seminar was an Audio Visual Presentation without Pat! The bureaucratic tangles had sent Pat back from the immigration counter of New Delhi Immigration authorities for reasons best known to them ! The well documented AV presentation made Pat come alive in the auditorium ! Pat is a Canadian photographer and mountain climber who was the first person in the world to climb the highest peaks of seven Continents: McKinley in North America, Aconcagua in South America, Everest in Asia, Elbrus in Europe, Kilimanjaro in Africa, Vinson Massif in Antarctica, and Puncak Jaya in Indonesia. This hour- long presentation described how Pat found the resources to help him reach and climb these peaks. Through over an hour that went past like a flash he took the audience through these summits and how he climbed them in different parts of the world. -

Nehru Gave Away Aksai Chin to China1

Nehru gave away Aksai Chin to China1 The Special Representatives (SR) of India and China will hold the 16th round of talks on their disputed border. Not much has been achieved so far; the best proof was of this that the Chinese could walk into India’s territory with impunity, pitch their tents for 3 weeks in Depsang Plains in the vicinity of the Karakoram pass in Ladakh and go back without any serious consequences on Sino-Indian relations. The SR’s meet could be routine if it was notfor the appointment of a new Chinese SR. Yang Jiechi, the former Foreign Minister was recently promoted State Councilor in the new Cabinet of Premier Li Keqiang. Ms. Hua Chunying, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson declared that the talks would help to “maintain the negotiation momentum, safeguard peace and tranquility in border areas, exchange views on bilateral relations as well as major international and regional issues, and push for comprehensive and in-depth development of relations.” The same words are repeated before each meeting, but this time, one is told that some ‘momentum’ has been ‘injected’ after the Chinese Premier’s visit to India last month. When Ms Hua says that “pending the final settlement of the issue, we should safeguard peace and tranquility of border areas”, she should be told that it is not India who pitched tents on Chinese soil, and ‘safeguarding the peace’ depends very much on Beijing. 1 Published in Niti Central on June 18, 2013 (URL not available). Considering the outrageous claims from China and the constant by moving goal posts (the LAC), the wishy-washy handling of the situation by Nehru decades ago did not help. -

Karakoram 1988

Karakoram 1988 PAUL NUNN (Plates 105, 106) The summer seems to have been marked by relatively good early weather for high snow peaks, but conditions were poor for high-altitude climbing in July and early August, causing disappointment on K2 to all parties and some problems elsewhere. Nevertheless, there was a continued trend towards creative ascents of new routes, on peaks varying from just below 8000m to small technical and not-so-technical mountains. The year began with the Polish-British-Canadian first attempt on K2 in winter. Bad weather caused immense difficulty in getting equipment to Base Camp, which delayed matters greatly. Andrzej Zawada, veteran of so many winter schemes, led the n-member team. They faced high winds and temperatures down to - 50°C. A high point of 7350m on the Abruzzi ridge was reached, but mostly the conditions seem to have been too bad to allow much progress. Roger Mear, Mike Woolridge and John Barry took part, though John did not go to Base Camp and Mike was ill. The first winter ascent of Broad Peak was something of a consolation prize. Maciej Berbeka and Alek Lwow set out on 3 March on an alpine-style ascent of the ordinary route. On 6 March Lwow decided to stay at a camp at 7700m after the exhausting struggle to reach that point through deep snow. Berbeka reached the top that night at 6pm and got down to 7900m before being forced to stop. Next morning he rejoined Lwow in poor weather and they made the descent safely. Both suffered frostbite.