Lovely Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

Unseen Femininity: Women in Japanese New Wave Cinema

UNSEEN FEMININITY: WOMEN IN JAPANESE NEW WAVE CINEMA by Candice N. Wilson B.A. in English/Film, Middlebury College, Middlebury, 2001 M.A. in Cinema Studies, New York University, New York, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in English/Film Studies University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Candice N. Wilson It was defended on April 27, 2015 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Film Studies Program Neepa Majumdar, Associate Professor, Film Studies Program Nancy Condee, Director, Graduate Studies (Slavic) and Global Studies (UCIS), Slavic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Director, Film Studies Program ii Copyright © by Candice N. Wilson 2015 iii UNSEEN FEMININITY: WOMEN IN JAPANESE NEW WAVE CINEMA Candice N. Wilson, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 During the mid-1950s to the early 1970s a subversive cinema, known as the Japanese New Wave, arose in Japan. This dissertation challenges critical trends that use French New Wave cinema and the oeuvre of Oshima Nagisa as templates to construct Japanese New Wave cinema as largely male-centered and avant-garde in its formal aesthetics. I argue instead for the centrality of the erotic woman to a questioning of national and postwar identity in Japan, and for the importance of popular cinema to an understanding of this New Wave movement. In short, this study aims to break new ground in Japanese New Wave scholarship by focusing on issues of gender and popular aesthetics. -

Women and Yaoi Fan Creative Work เพศหญิงและงานสร้างสรรค์แนวยาโอย

Women and Yaoi Fan Creative Work เพศหญิงและงานสร้างสรรค์แนวยาโอย Proud Arunrangsiwed1 พราว อรุณรังสีเวช Nititorn Ounpipat2 นิติธร อุ้นพิพัฒน์ Krisana Cheachainart3 Article History กฤษณะ เชื้อชัยนาท Received: May 12, 2018 Revised: November 26, 2018 Accepted: November 27, 2018 Abstract Slash and Yaoi are types of creative works with homosexual relationship between male characters. Most of their audiences are female. Using textual analysis, this paper aims to identify the reasons that these female media consumers and female fan creators are attracted to Slash and Yaoi. The first author, as a prior Slash fan creator, also provides part of experiences to describe the themes found in existing fan studies. Five themes, both to confirm and to describe this phenomenon are (1) pleasure of same-sex relationship exposure, (2) homosexual marketing, (3) the erotic fantasy, (4) gender discrimination in primacy text, and (5) the need of equality in romantic relationship. This could be concluded that these female fans temporarily identify with a male character to have erotic interaction with another male one in Slash narrative. A reason that female fans need to imagine themselves as a male character, not a female one, is that lack of mainstream media consists of female characters with a leading role, besides the romance genre. However, the need of gender equality, as the reason of female fans who consume Slash text, might be the belief of fan scholars that could be applied in only some contexts. Keywords: Slash, Yaoi, Fan Creation, Gender 1Faculty of -

Queer Fears Programme Final 2019

QUEER FEARS A ONE DAY SYMPOSIUM ON NEW QUEER HORROR FILM AND TELEVISION FRIDAY, 28TH JUNE 2019, UNIVERSITY OF HERTFORDSHIRE This symposium/project is part of the ongoing work of the Media Research Group (Humanities) at the University of Hertfordshire. SYMPOSIUM PROGRAMME 9am Registration (Cinema Foyer, coffee and tea provided) 10am Conference Opening Address and Welcome (Cinema Auditorium downstairs) 10.15-11.45pm Panel 1: In and Out of the Closet - (Chair: Darren Elliott-Smith, University of Herts) Chris Lloyd (University of Hertfordshire) – American Horror Story – Queer Fears in the USA. Tim Stafford (Independent Scholar) – All’s Queer in Love and War-lock: The Problematic Queer Space in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina The Teenage Witch. Ben Wheeler (University of Hertfordshire) - Losing Boys, Falling Down, Gaining Nipples: The Queer Fears of Joel Schumacher. 11.45-12.00pm Coffee Break 12.00-1.30pm Panel 2: Queer Performative Horror - (Chair: Laura Mee, University of Hertfordshire) Valeria Lindvall (University of Gothenburg, Sweden) – Dragula and Queer Performance. Daniel Sheppard (University of East Anglia) – The Babadook and New Realisations of the Monster Queer. Lexi Turner (Cornell University) – The Dance of An Other – Queer Dance as Ritual in Suspiria and Climax. 1.30-2.15pm Lunch and Refreshments (Cinema Foyer Downstairs) 2.15 - 3.45pm Panel 3: Consuming Queerness and Other Gross Tales… (Chair: Christopher Lloyd, University of Hertfordshire) Robyn Ollett (University of Teeside) - What do you eat? Queering the Cannibal in Ducourneau’s RAW. Eddie Falvey (University of Exeter) - Conspicuous Corporeality - Monstrousness as Queer in Ducourneau’s RAW. Laura Mee (University of Hertfordshire) - Sick Girls, Bloodhound Bitches, Feral Females and Weirdos: Queer Women in the films of Lucky McKee 3.45 – 4.00pm Coffee Break 4.00 - 5.30pm Panel 4: Frightfully Problematic Queerness (Chair: Agustin Rico- Albero, University of Hertfordshire) Siobhan O’Reilly (University of Hertfordshire) - Queer Horror and Transphobia. -

1 07 Ghost 2 11 Eyes 3 801 TTS Airbat 4 Abenobashi Mahou

1 07 Ghost 37 Amnesia (Movie) 2 11 Eyes 38 Angel Beats 3 801 TTS Airbat 39 Angel Sanctuary 4 Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai 40 Angel's Feathers (Yaoi) 5 Abrazo de Primavera (Yaoi) 41 Antique Bakery 6 Accelerado (Hentai) 42 Ao no Exorcist 7 AD Police 43 Aoi Bungaku 8 Afro Samirai Resurrection 44 Aoi Hana 9 Afro Samurai 45 Appleseed 10 After the School in the Teacher's Lounge 46 Aquariam Age 11 Agent Aika 47 Araiso (Yaoi) 12 Ah! Megamisama 48 Arakawa Under The Bridge 13 Ah! Megamisama (Movie) 49 Arashi no Ato (Manga - Yaoi) 14 Ah! Megamisama (OVA) 50 Argento Soma 15 Ai no Kusabi (Yaoi) 51 Aria -Arietta- (OVA) 16 Ai Yori Aoshi 52 Aria The Animation 17 Ai Yori Aoshi - Enishi - 53 Aria The Navegation 18 Aika R-16 54 Aria The Origination 19 Aika Zero 55 Aria The Scarlet Ammo 20 Air 56 Armitage III 21 Air (OVA) 57 Asterix El Galo (Movie) 22 Air Gear 58 Asterix y Cleopatra (Movie) 23 Air Tonelico (Movie) 59 Asterix y La Sorpresa del Cesar (Movie) 24 Aiso Tsukash (Manga - Yaoi) 60 Asterix y las 12 Pruebas (Movie) 25 Aitsu no Daihonmei (Manga - Yaoi) 61 Asterix y Los Bretones (Movie) 26 Aitsu no Heart Uihi wo Tsukeru (Manga - Yaoi) 62 Asterix y Los Vikingos (Movie) 27 Akane Maniac 63 Asu no Yoichi 28 Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka 64 Asura Criyn' 29 Akira 65 Asura Criyn' II 30 Akuma no Himitsu (Manga - Yaoi) 66 Asuza 31 Amaenaideyo 67 Avatar Libro 1 Agua 32 Amaenaideyo - Especial - (OVA) 68 Avatar Libro 2 Tierra 33 Amaenaideyo Katsu 69 Avatar Libro 3 Fuego 34 Amagami SS 70 Avenger 35 Amame Pecaminosamente (Manga - Yaoi) 71 Ayakashi Japanese Classic Horror -

Nodame Cantabile: a Japanese Television Drama and Its Promotion of Western Art Music in Asia

NODAME CANTABILE: A JAPANESE TELEVISION DRAMA AND ITS PROMOTION OF WESTERN ART MUSIC IN ASIA Yu-Ting Tung A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2009 Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Robert Fallon © 2009 Yu-Ting Tung All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor The fictional Japanese TV drama series, Nodame Cantabile (!"#$%&'()), based on the lives of Western art music performance majors in a Japanese music conservatory, has successfully reached out and appealed to the Japanese common audience since it was first aired in Japan in October, 2006. It has also attracted an international following, been aired in various Asian countries (including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Malaysia), and found mass audiences beyond national boundaries. Why is a TV drama depicting such a specific group (i.e. music majors) able to cater to a mass audience in Japan and even to millions of viewers beyond Japan? In this thesis, I will argue that Nodame Cantabile not only has the typical prerequisites to be a successful Japanese TV drama, it also enchants its spectators by employing a unique, almost unprecedented approach—using Western art music as the thematic music and main soundtrack— which results in a whimsical, sensational, cross-cultural success. By contrast, most music in similar drama series uses Japanese pop music and electronic music. I will decode how this drama attracts mass audiences by interpreting/elucidating it from different perspectives, including: 1) how it portrays/reflects the Japanese music conservatory culture; 2) how it reflects the long-term popularity of certain Western art music compositions in/among Japanese music consumers; and, most interestingly; 3) how this drama further changes the perception of mass audiences, especially fans in Taiwan, about Western art music, and serves to increase the popularity of this music in Asian countries. -

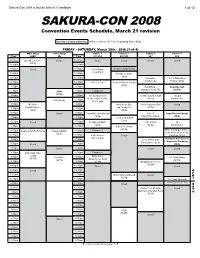

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

ANIMAX Hong Kong Feb 2009

ANIMAX Hong Kong Feb 2009 9-Dec-08 MON-FRI SAT SUN 6A 6A B-Legend! B-daman ##(52x30')[12/05-2/16](rr) / Hiwou War Chronicles ## (26x30')[2/17-3/24](rr) Final Fantasy Unlimited ## [rpt of Sat 1030A] Alice Academy## (26x30')[1/02-2/06](rr) / Captain Tsubasa ~ Road to Dream ##(52x30')(2/09-4/21)(rr) Ranma 1/2 ep 11- 161(150x30')[7/05- 7A 7A Kamichu ## / La Corda D'Oro Primo Passo ##[rpt of Mon-Fri 430P] 3/21/09](rr) Astro Boy ##(50x30')[12/15-2/19](rr) / Chibi Maruko-Chan (Season 1)## (52x30')[2/20-5/04](rr) 8A Astro Boy ## 8A Chibi Maruko-Chan (Season 2)## / Black Cat [rpt of Mon-Fri 4P] (49x30')[1/11-3/15](rr) Flame of Recca / Spooky Kitaro ## [rpt of Mon-Fri 5P] Samurai Deeper Kyo/ 9A 9A God(?) Save Our King (Season 1) / Big Windup! ## [rpt of Mon - Fri 530P] Prince of Tennis (Season 1) ##[rpt of Mon-Fri 630P] Kamichu ## / La Corda D'Oro Primo Passo ##[rpt of Mon-Fri 430P] Air Gear[PG] ## [rpt of Thu 10P]/ Bincho-Tan 10A 10A B-Legend! B-daman ## / Hiwou War Chronicles ## [rpt of Mon - Fri 6A] (6X30') [2/22- 3/8](rr) Astro Boy ## / Chibi Maruko-chan ## [rpt of Mon - Fri 730A] Final Fantasy Unlimited Toward the Terra/ REC 11A ##(25x30')[12/01-2/28](rr) [rpt of Mon 10P] 11A Alice Academy ## / Captain Tsubasa ~ Road to Dream ## [rpt of Mon-Fri 630A] Slam Dunk [rpt of Mon-Fri 6P] Toward the Terra/ REC/ Darker than Black [rpt of 12N Mr. -

Hong Kong Martial Arts Films

GENDER, IDENTITY AND INFLUENCE: HONG KONG MARTIAL ARTS FILMS Gilbert Gerard Castillo, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2002 Approved: Donald E. Staples, Major Professor Harry Benshoff, Committee Member Harold Tanner, Committee Member Ben Levin, Graduate Coordinator of the Department of Radio, TV and Film Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, TV and Film C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castillo, Gilbert Gerard, Gender, Identity, and Influence: Hong Kong Martial Arts Films. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2002, 78 pp., references, 64 titles. This project is an examination of the Hong Kong film industry, focusing on the years leading up to the handover of Hong Kong to communist China. The influence of classical Chinese culture on gender representation in martial arts films is examined in order to formulate an understanding of how these films use gender issues to negotiate a sense of cultural identity in the face of unprecedented political change. In particular, the films of Hong Kong action stars Michelle Yeoh and Brigitte Lin are studied within a feminist and cultural studies framework for indications of identity formation through the highlighting of gender issues. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank the members of my committee all of whom gave me valuable suggestions and insights. I would also like to extend a special thank you to Dr. Staples who never failed to give me encouragement and always made me feel like a valuable member of our academic community. -

Open Final Version of Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications HORROR GLOBAL, HORROR LOCAL: A CROSS-CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF TORTURE PORN, J-HORROR, AND GIALLO AS CONTEMPORARY MANIFESTATIONS OF THE HORROR GENRE A Thesis in Media Studies by Lauren J. DeCarvalho © 2009 Lauren J. DeCarvalho Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2009 ii The thesis of Lauren J. DeCarvalho was reviewed and approved* by the following: John S. Nichols Professor of Communications Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research Matthew F. Jordan Assistant Professor of Media Studies Thesis Advisor Marie C. Hardin Associate Professor of Journalism Jeanne L. Hall Associate Professor of Film and Video *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT The overbearing effects of Hollywood continue to blur the lines of distinction between national and global cinema, leaving scholars to wonder whether the latter type of cinema has since trumped the former. This thesis explores the depths of this perplexity by looking at the cultural differences in post-1990s horror films from three countries: the United States, Japan, and Italy. Scholarship on women in horror films continues to focus on the feminist sensitivities, without the slightest regard for possible cultural specificities, within the horror genre. This, in turn, often collapses the study of women in horror films into a transnational genre, thereby contributing to the perception of a dominant global cinema. Therefore, it is the aim of the author to look at three culturally-specific subgenres of the horror film to explore their differences and similarities.