ASEAN School Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report for ASEAN School Games 2014

Report for ASEAN School Games 2014 15th December 2014 By Andrew Pirie PSC Research Assistant Office of Commissioner Gomez The Philippines finished with fourth place at the ASEAN School Games behind Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. The Philippines garnered 11 Golds, 14 Silvers and 22 Bronzes a total of 47 medals its best ever finish since the ASEAN School Games revival in 2010. The Philippines was coming second to last leading into the last day of competition however Women’s Basketball and SEA Games Champion Princess Superal bumped the Philippines up ahead of Vietnam and Singapore with last minute gold efforts. The Philippines has finished second to last or last the last three editions so this was its best ever performance. However DEPED Regional Director Ms. Alameda pointed out that as the host the Philippines a country with the same population as Thailand and Malaysia should have won a lot more Thailand won 41 Gold’s and Malaysia 35 gold’s. Ms. Alameda pointed out she looked forward to having talks and more cooperation with the POC, PSC, NSAs, UAAP board and others on ways to improve the overall medal standing of the games and was open to ideas and suggestions. This meet was for athletes born in 1996 and under represented by eight member nations of the South East Asian Federation. All countries competed here except Cambodia, Myanmar and Timor Leste. Athletics While Athletics did not get its anticipated six gold medal haul it did exceed its total medal count of 19, with 21 medals in total. 2 Golds, 9 Silvers and 10 Bronzes. -

BBSS Westories 2018

BUKIT BATOK SECONDARY SCHOOL www.bukitbatoksec.moe.edu.sg Learning to take Responsible Risks can pay off later in life CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT: Preparing for Future Challenges alking along our common corridor, one cannot help but notice the eye- Wcatching signboards hanging from the ceiling. These hard-to-miss Habits of Mind (HOM) visuals are daily reminders of good learning habits and thinking dispositions like “Listening with Empathy and Understanding” that every student in BBSS practises to prepare himself or herself for future challenges. These HOM dispositions have been the drivers of student character development in the school since 2003. We believe in Activity-Based Learning in which students go through the learning cycle of Taught, Caught and Practice. Starting with the disposition of “Gathering Data Through All Senses”, our Sec 1 students learn to tap their five senses to observe the school environment as they walk around the school Our Habits of Mind posters constantly remind our Our challenging outdoor camp for Sec 3 students during their HOM lessons. They should be able students to be mindful teaches teamwork to describe these locations vividly to parents or friends who have never been to that part of the to “Persist” and “Think Interdependently” as HOM dispositions are practised every day – in school before. they negotiate high-obstacle courses and work class, at CCA, during Values in Action (VIA) Sec 2 students hone the disposition of “Taking in teams to reach common goals. activities and on overseas trips. They are reflected upon frequently through platforms like Responsible Risks” through playing an exciting Graduating cohorts facing the challenging reflection logs post-activity, using the disposition game of Stacko in which they steadily pull out national examinations would apply the of “Thinking About Your Thinking”. -

THE ASEAN WORK PLAN on SPORTS 2016-2020 ASEAN Senior

THE ASEAN WORK PLAN ON SPORTS 2016-2020 ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Sports (SOMS) 2019 THE ASEAN WORK PLAN ON SPORTS 2016-2020 No. Programme Lead Timeline 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 KEY ELEMENT 1: Promote awareness of ASEAN through sporting activities that bring the ASEAN peoples together and engages and benefits the community Priority Area 1.1: Inclusion of ASEAN traditional sports and games (TSG) and existing sports events to further instill values of mutual understanding, friendship and sportsmanship among ASEAN nationals 1 Support the regular conduct as well as new initiatives which showcase ASEAN TSG in Malaysia x x x x x ASEAN and beyond 2 Conduct relevant clinics and courses for coaches/ technical officials (judges, umpires, Malaysia x x x referees, and others) on ASEAN traditional sports (e.g. martial arts, sepak takraw, traditional rowing, lion dance) to promote the rich and diverse heritage of ASEAN, especially in traditional sports to broader audience 3 Create promotional video on the Inventory of ASEAN Traditional Games and Sports to be Malaysia x x shared widely on ASEAN publication tools and by related stakeholders 4 Dissemination of information / regular updates on ASEAN TSG by existing and newly Malaysia x x created ASEAN-related publication tools (Dissemination of booklet on ASEAN TSG in conjunction with Visit ASEAN Year 2017) 5 Further promote the Inventory of ASEAN Traditional Games and Sports Book in ASEAN Malaysia x x cultural/educational festivals and seminar events, especially on TSG Priority Area 1.2: Established -

Press Release Asg.Pdf

PRESS RELEASE Ministry of Education 1 Jun 2011 Singapore hosts 3rd ASEAN Schools Games 2011 1. Singapore will host the 3rd ASEAN Schools Games (ASG) from 1 – 7 July 2011. The ASG aims to promote ASEAN solidarity through school sports, while providing opportunities for school athletes to benchmark their sporting talents in the ASEAN region. This is the first time that Singapore is hosting the ASEAN Schools Games. 2. Come July, over 1,100 student-athletes from 7 ASEAN nations (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) will compete in a total of 12 sports – Badminton, Basketball, Golf, Gymnastics, Hockey, Netball, Sepak Takraw, Swimming, Table Tennis, Tennis, Track and Field, and Waterpolo (Boys only). To participate, athletes must be below 18 years of age and be full-time students of schools or junior colleges in the participating ASEAN countries. (Refer to Annex A for information on the ASG and ASEAN Schools Sports Council). 3. The competitions will be held at 13 venues across the island. Student- athletes and officials will be housed at the Games Village in Nanyang Technological University. There will be over 200 student-athletes in the Singapore’s contingent for the 3rd ASG. 4. Student-athletes and officials will participate in a culture and education programme (CEP) during their stay in Singapore that promotes understanding and cross-cultural interaction. The CEP comprises a cultural festival during the opening of the Games Village on 30 Jun, evening cultural showcases during the Games and a learning journey. Through the ASG, our schools can also enhance their students’ knowledge of ASEAN and how sports has brought ASEAN nations together. -

The ASEAN Magazine Issue 4 August 2020

The A SEAN ISSUE 04 | AUGUST 2020 YOUTH AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT BUILDING BLOCKS FOR BETTER COMMUNITIES ISSN 2721-8058 CONVERSATIONS VIEWPOINT INSIDE VIEW ASEAN’s Young and Inspiring Singaporean Olympic Education, Training and Sports Social Entrepreneurs Champion Joseph Schooling for Youth Development s of ight R n and n and G ome Wome ender W en hildr are C L elf t ab W en or ial pm oc elo ACW S ev D nd ACWC a SLOM nt e on m ti SOMSWD C p a iv o ic i l d l S ve ra e e E rvi D y c l rt e a e r v u o AMMW R P SOMRDPE SOM-ACCSM d n AMMSWD ALMM a AMRDPE ACCSM H s e t r a o lt p ASEAN SOCIO-CULTURAL h S SOMS COMMUNITY SOMHD n o l i i t c AMMS a AHMM n Ministerial Bodies r u o o b C a l and Senior Officials l C o C c S s A e t s r a e o i t i f d l i e n o c e o a b i t l f t t i a a d SOM-ED ASED r AMMDM c n m o u ASCC a t d l m c i E e o c t s C n n Council ’ u C e s l o S m a C S i e A c C g g f C a S n ACDM O n A o a r s m o t M i r a n o s r e t e AMMY S p r COP-AADMER p o st u f a S e f is o SOMY D Y SOCA o u t h AMRI AMME AMCA COP-AATHP SOMRI ASOEN t n e In m fo n r o m COCI* vir ati En on SOMCA COM Cu ltu re e an az d y H Art ar s und sbo Tran Ministerial Bodies Sectoral Bodies * takes guidance from and reports to both AMCA and AMRI AMRI-ASEAN Ministers Responsible for Information AMMDM-ASEAN Ministerial Meeting SOMRDPE-Senior Officials Meeting on Rural on Disaster Management Development and Poverty Eradication AMCA-ASEAN Ministers Responsible for Culture and Arts COP-AADMER-Conference of the Parties to the ASEAN SOMSWD-Senior Officials -

Singapore Age-Group Records As of November 2011

Singapore Age-Group Records As of November 2011 U-19 BOYS Event Record Name D.O.B Country Established 100 metres 10.53 Kang Li Loong Calvin April 16, 1990 Jakarta, Indonesia Asian Jr. Championship June 13, 2008 200 metres 21.8 Chay Wai Sum - - - 1985 21.87 Poh Seng Song January 30, 1983 Singapore ASEAN School August 4, 1999 400 metres 47.97 Ng Chin Hui January 12, 1994 Jakarta, Indonesia SEA Junior June 18, 2011 800 metres 1:52.37 Sinnathambi Pandian November 7, 1967 Singapore - 1985 1500 metres 3:59.4 Pillai Arjunan Saravanan - - - 1988 5000 metres 15:19.0 Mirza Namazie July 17, 1950 - - September 19, 1967 3000m S/C 9.24.64 Mathevan Maran - - - August 25, 1989 110m Hurdles (0.991m) 14.24 +1.1 m/s Ang Chen Xiang July 3, 1994 Singapore SAA T&F Series 2 February 19, 2011 400m Hurdles (0.914m) 53.6 Aljunied Syed Abdul Malik - - - 1986 High Jump 2.08 Yap Kuan Yi Wayne April 11, 1992 - Negeri Sembilan Open April 26, 2009 Long Jump 7.62 Goh Yujie Matthew July 17, 1991 Vientiane, Laos SEA Games December 15, 2009 Triple Jump 14.78 Alfred Tsao - - - 1978 Pole Vault 4.81 Lim Zi Qing Sean July 5, 1993 Singapore S'pore U23/Open C'ship June 25, 2011 Javelin (800 gm) 55.19 Koh Thong En October 29, 1991 Singapore - May 31, 2009 Shot Put (7.26 kg) 14.66 Wong Kai Yuen June 17, 1994 Singapore S'pore U23/Open C'ship June 25, 2011 Shot Put (6 kg) 16.07 Wong Kai Yuen June 17, 1994 Singapore SAA T&F Series 4 May 8, 2011 Shot Put (5 kg) 18.63 Wong Kai Yuen June 17, 1994 Singapore ASEAN School Games July 3, 2011 Discus (2 kg) 47.98 Wong Tuck Yim James January 10, 1969 - - 1987 Discus (1.75 kg) 49.60 Wong Wei Gen Scott September 9, 1990 Singapore ASEAN School Games April 6, 2008 Discus (1.5 kg) 53.88 Wong Wei Gen Scott September 9, 1990 Singapore ASEAN School T&F C'ship August 26, 2008 10KM walk (T) 46:25.76 Jairajkumar Jeyabal - - - December 5, 1996 Compiled by SAA Statistician. -

Sheikha Moza: Set a World Synergy Crucial for Labour Reform Goals’

WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 2, 2019 SAFAR 3, 1441 VOL.13 NO. 4753 QR 2 Fajr: 4:10 am Dhuhr: 11:23 am Asr: 2:47 pm Maghrib: 5:21 pm Isha: 6:51 pm MAIN BRANCH LULU HYPER SANAYYA ALKHOR US 8 Business 9 Doha D-Ring Road Street-17 M & J Building Trump administration QSE launches fifth FINE MATAR QADEEM MANSOURA ABU HAMOUR BIN OMRAN HIGH : 42°C Near Ahli Bank Al Meera Petrol Station Al Meera pushes back hard against annual IR Excellence LOW : 30°C alzamanexchange www.alzamanexchange.com 44441448 impeachment probe Programme ‘State, private sector Sheikha Moza: Set a world synergy crucial for labour reform goals’ day for protection of education QNA DOHA ILO official praises Qatar She makes the pitch QATAR has embarked on an ambitious programme to re- Qatar is carrying out a at the UN Office form Labour laws in order to improve workers’ rights, Min- pivotal role in reforming la- in Geneva while ister of Administrative Devel- bour policies, said Michelle highlighting conse- opment, Labour and Social Leighton, the chief of the Affairs Yousuf Mohammed Labour Migration Branch quences of armed al Othman Fakhroo said at a for the International Labour conflicts for children’s high-level forum in Doha on Organization (ILO). She Tuesday. said these policies would education Several key reforms have “undoubtedly” contribute to already been adopted and boosting its economy. QNA many are in the pipeline, the Addressing the high-level GENEVA minister said, terming such forum in Doha on Tuesday, measures the results of Qatar’s HH Sheikha Moza bint commitment to achieving the Leighton said the reforms Nasser called for setting aside UN Sustainable Development implemented by Qatar in an international day for the Goals. -

Achiever's Academy Shivamogga March-2019

ACHIEVER’S ACADEMY SHIVAMOGGA MARCH-2019 www.achieversacademyshivamogga.com Page 1 ACHIEVER’S ACADEMY SHIVAMOGGA MARCH-2019 Dear Readers, This Monthly Capsules is a complete docket of important news and events that occurred in a month of March 2019. We have compiled important & Expected questions which can be asked in upcoming Banking & Insurance Exams, interviews and all upcoming Competitive exams. SL NO. CONTENTS Page No. 1 BANKING AWARENESS 3-11 2 AWARDS & HONOURS 12-20 3 BUSINESS & MOUS 20-23 4 NATIONAL NEWS 23-38 5 INTERNATIONAL NEWS 38-46 6 NEW APPOINTMENTS & RESIGNS 47-56 7 RANKS & REPORTS 57-62 8 SCHEMES & APPS 62-67 9 BOOKS & AUTHORS 68 10 DEFENCE, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 69-72 11 IMPORTANT DAYS & EVENTS 73-77 12 SPORTS NEWS 78-86 13 OBITUARIES 87-89 www.achieversacademyshivamogga.com Page 2 ACHIEVER’S ACADEMY SHIVAMOGGA MARCH-2019 Banking & Financial Awareness Cabinet nod for Rs 1,450 cr to purchase RBI stake in National Housing Bank The Union Cabinet approved an expenditure of Rs 1,450 crore for purchase of the Reserve Bank of India-held shares in the National Housing Bank (NHB), Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced following a Cabinet meeting in New Delhi. The RBI currently holds 100 per cent stake in the NHB. RBI, Bank of Japan sign Bilateral Swap Arrangement Reserve Bank of India and Bank of Japan have signed a Bilateral Swap Arrangement (BSA).It was negotiated between India and Japan during the visit of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Tokyo in October 2018.The BSA provides for India to access 75 billion US dollars whereas the earlier BSA had provided for 50 billion dollars.The BSA was approved by the Union Cabinet in January 2019. -

Sub-Saharan Africa

AFRICA REGION THE WORLD BANK ESMI 2 Symposium on Power Sector Reform and Efficiency Improvement in Sub-SaharanAfrica Johannesburg, December 5-8, 1995 Report No. 182/96 June 1996 Jointly Organized by The Africa Region of the World Bank and The Joint UNDP/World Bank Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme (ESMAP) EnergySedor Management sistance Programme JOINT UNDP / WORLD BANK ENERGY SECTOR MANAGEMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAMME (ESMAP) PURPOSE The Joint UNDP/World Bank Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme (ESMAP) is a special global technical assistance program run by the World Bank's Industry and Energy Department. ESMAP provides advice to governments on sustainable energy development. Established with the support of UNDP and 15 bilateral official donors in 1983, it focuses on policy and institutional reforms designed to promote increased private investment in energy and supply and end-use energy efficiency; natural gas development; and renewable, rural, and household energy. GOVERNANCE AND OPERATIONS ESMAP is govemed by a Consultative Group (ESMAP CG), composed of representatives of the UNDP and World Bank, the governments and other institutions providing financial support, and the recipients of ESMAP's assistance. The ESMAP CG is chaired by the World Bank's Vice President, Finance and Private Sector Development, and advised by a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) of independent energy experts that reviews the Programme's strategic agenda, its work program, and other issues. ESMAP is staffed by a cadre of engineers, energy planners, and economists from the Industry and Energy Department of the World Bank. The Director of this Department is also the Manager of ESMAP, responsible for administering the Programme. -

Asean Schools Sports Council General Rules and Regulations for All Games

MARIKINA CITY 6TH ASEAN SCHOOL GAMES 2014 PHILIPPINES ASEAN SCHOOLS SPORTS COUNCIL GENERAL RULES AND REGULATIONS FOR ALL GAMES 1. Rules & Regulations All ASSC Championships will be played under the current official Rules adopted by the respective International Sports Federations, the Constitution of the ASSC and these General Rules and Regulations of the ASSC. 2. Eligibility 2.1. Each country is allowed to send only one boys‟ and one girls‟ team. 2.2. Players must only be 18 years of age or younger as on 1st January of the year of the Games (i.e. Players were born in 1996 or later will be eligible for the 6h ASG in 2014) 2.3. Players must be full- time bona fide students of schools/junior colleges of the respective countries. Players who are citizen of country „A‟ but studying full-time in country „B‟ can only represent country „B‟. 2.4. Polytechnic / University students will not be allowed to take part. 3. Composition of Contingent 3.1. Each contingent shall comprise the following : Table 1 - Composition of Contingent (Officials*) Category Officials No. of Pax A Senior Ministry of Officials (SMO) 2 B Chef-De-Mission (CDM) 1 C Deputy Chef-De-Mission (Dy CDM) 1: If less than or equal to 150 athletes 2: If more than 150 athletes 3: If less than or equal to 150 athletes D Secretariat 4: If more than 150 athletes E Medical/Support Team 3 F Media 3 *: Not including Team Managers, Coaches and Referees Table 2 - Composition of Contingent (Team Managers, Coaches, Referees & student Athletes) GAMES OFFICIALS PARTICIPANTS Track and Field 2 officials -

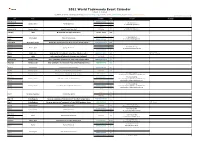

2021 World Taekwondo Event Calendar

2021 World Taekwondo Event Calendar (subject to change) ※ Grade of event is distinguished by colour: Blue-Kyorugi, Red-Poomsae, Green-Para, Purple-Junior, Orange-Team, (as of 15th January, 2021) Date Place Event Discipline Grade Contacts Remarks February 20-21 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (T) 0090 530 575 27 00 Istanbul, Turkey Turkish Open 2021 February 22 CADET N/A (E ) [email protected] February 23 JUNIOR N/A (T) 0090 530 575 27 00 February 25-26 Istanbul, Turkey Turkish Poomsae Open 2021 POOMSAE G-1 (E ) [email protected] February Online World Taekwondo Super Talent Show TALENT SHOW N/A - March 6 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) 359 8886 84548 Sofia, Bulgaria Ramus Sofia Open 2021 March 7 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E ) [email protected] March 8-10 Riyad, Saudi Arabia Riyadh 2021 World Taekwondo Women's Open Championships SENIOR KYORUGI TBD March 12 CADET N/A (T) 34 965 37 00 63 March 13 Alicante, Spain Spanish Open 2021 JUNIOR N/A (E ) [email protected] March 14 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (PSS : Daedo) March Wuxi, China Wuxi 2020 World Taekwondo Grand Slam Champions Series SENIOR KYORUGI N/A Postponed to 2021 March Online Online 2021 World Taekwondo Poomsae Open Challenge I POOMSAE G-4 March 26-27 Amman, Jordan Asian Qualification Tournament for Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games SENIOR KYORUGI N/A March 28 Amman, Jordan Asian Qualification Tournament for Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games PARA KYORUGI G-1 April 8-11 Sofia, Bulgaria European Senior Championships SENIOR KYORUGI G-2 April 19 Beirut, Lebanon 6th Asian Taekwondo Poomsae Championships POOMSAE G-4 -

SEA Games Swimming Rankings Complete 2013.Pdf

SEA Games Rankings 2013 Issue 5 Swimming 01.01.14 Compiled by Andrew Pirie ATFS Statiscian/PSC Consultant 50M Freestyle 1 LIM Darren Fang Yue SIN 22.73 Nat Championships Singapore 25.06.13 2 HUONG Quy Phuoc VIE 22.90 Championships Barcelona 31.07.13 3 Fauzi Sadik Triady INA 23.12 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 15.12.13 4 Kaiyi Russell Ong SIN 23.14 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 15.12.13 5 SCHOOLING Joseph SIN 23.34 2013 Area Grand Prix Charlotte, USA 09.05.13 6 Gavin Alexander Lewis THA 23.40 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 15.12.13 7 LIM Ching Hwan MAS 23.46 AYG Nanjing 22.08.13 8 BEGO Daniel MAS 23.68 56th Malaysia National Open Kuala Lumpur 16.05.13 9 PAPUNGKORN Ingkanont THA 23.80 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 15.12.13 10 LING Clement SIN 23.83 44th Singapore National Age Singapore 19.03.13 * Glenn Victor Sutanto INA 23.79c FINA World Cup Singapore 05.10.13 100M Freestyle 1 HOANG Quy Phuoc VIE 49.60 FINA World Champs Barcelona 31.07.13 2 Triadi Fauzi Sidiq INA 49.99 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 05.10.13 3 Danny Yeo Kai Quan SIN 50.51 9th Singapore National Swimming Nyapitdaw 25.06.13 4 Ching Hwang Lim MAS 50.87 44th National Age Grade Singapore 19.03.13 5 Daniel Bego MAS 51.21 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 13.12.13 6 LIM Darren SIN 51.25 9th Singapore National Swimming Singapore 25.06.13 7 NG Kai Wee Rainer SIN 51.41 FINA World Champs Barcelona 31.07.13 8 Clement Lim SIN 51.43 9th Singapore National Swimming Singapore 25.06.13 9 SCHOOLINH Joseph SIN 51.47 2013 Grand Prix at Charl Charlotte 09.05.13 10 Jessie Khing Lacuna PHI 51.52 SEA Games Nyapitdaw 13.12.13 * Triadi Fauzi Sidiq INA 49.85c FINA