DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

Screendollars August 10, 2020 About Films, the Film Industry No

For Exhibitors Screendollars August 10, 2020 About Films, the Film Industry No. 129 Newsletter and Cinema Advertising Happy birthday to Stan Durwood, the Founder of AMC Theatres, born 100 years ago on August 5, 1920. Stan was a highly motivated and creative entrepreneur, who expanded the family theatre business he took over in 1960 to become one of the largest theatre chains in the world. He is credited with many innovations that transformed the movie business, most notably, the creation of the multiplex cinema and the invention of the arm-rest cup holder. Purpose-built, multiple- screen, cinema entertainment complexes became Parkway Twin Theatres, the first Multiplex, The dominant force in exhibition in the late 20th century, growing a $2B annual industry in opened in Kansas City on July 12, 1963 1975 to a $6B industry in 1997. He was a proud son of Kansas City, where AMC is based. Welcome Back - Looking Forward to a Brighter 2021 As theatres begin to re-open and the industry comes back to life, we take stock of the positive signs of what lies ahead. The movie business has been interrupted, but it is not broken. Despite the significant challenges this year, when new movies return to theatres, audiences will follow. When circumstances permit, people are going to say to themselves, “I have been stuck at home for months watching streaming, and I’m tired of that. Now I want go out with friends and family, see other people, and experience something fantastic." Screendollars has produced this three-minute video, which previews the Must-See Movies which will be coming to theatres in 2021. -

Donald Mckayle's Life in Dance

ey rn u In Jo Donald f McKayle’s i nite Life in Dance An exhibit in the Muriel Ansley Reynolds Gallery UC Irvine Main Library May - September 1998 Checklist prepared by Laura Clark Brown The UCI Libraries Irvine, California 1998 ey rn u In Jo Donald f i nite McKayle’s Life in Dance Donald McKayle, performer, teacher and choreographer. His dances em- body the deeply-felt passions of a true master. Rooted in the American experience, he has choreographed a body of work imbued with radiant optimism and poignancy. His appreciation of human wit and heroism in the face of pain and loss, and his faith in redemptive powers of love endow his dances with their originality and dramatic power. Donald McKayle has created a repertory of American dance that instructs the heart. -Inscription on Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award orld-renowned choreographer and UCI Professor of Dance Donald McKayle received the prestigious Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival WAward, “established to honor the great choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of our modern dance heritage,” in 1992. The “Sammy” was awarded to McKayle for a lifetime of performing, teaching and creating American modern dance, an “infinite journey” of both creativity and teaching. Infinite Journey is the title of a concert dance piece McKayle created in 1991 to honor the life of a former student; the title also befits McKayle’s own life. McKayle began his career in New York City, initially studying dance with the New Dance Group and later dancing professionally for noted choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Sophie Maslow, and Anna Sokolow. -

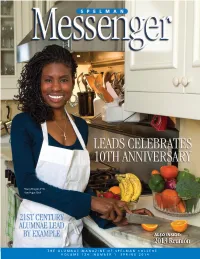

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

To View the Sankofa African Heritage Book List

A B C D E F COPY- TITLE AUTHORS ED PUBLISHER(S) COVER ANNOTATION 1 RIGHT African Origins of the Majors Yosef Ben jochannan 1970- All Western religions had 2 Western Religions Yosef Ben Jochannan Publishing 360pp Paper their beginnings in Africa The Encyclopedia of the 1999- African and African American 3 AFRICANA Kwame-Gates, editors Basic Civitas Books 2045pp Cloth Experience 2002- 4 Africans Americans David Boyle Barrons 127pp Cloth Coming to America Today, we live in a changed Al on America, The Right Reverend Kingsenton Publishing 2002- America, changed by people 5 Al Sharpton Karen Hunter Group 280pp Cloth who risk their own lives. 2009- What Should Black People Do 6 America I Am Legends Foreword : Tavis Smiley Smiley books 180pp Paper Now? Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, 2008- and Forgotten Founders who 7 America's Hidden History Kenneth C. Davis Smithsonian Books 265pp Cloth shaped a Nation Ancient Egypt, The Light of the 1990- A work of reclamation and 8 World,Vol 1-B and vol.2--A Gerald Massey ECA Associates 750pp Paper restitution in twelve volumes The teaching and prophetic wisdom of the Seven 1999- Hermetic laws of Ancient 9 Ancient Future Wayne B. Chandler Black Classic Press 246pp Paper Egypt 2009- The U.S. Commission on Civil 10 And Justice For All Mary Frances Berry Knopf Publishers 425pp Cloth Rights 1995- Everyday liife ritual and court 11 Art and Craft in Africa Laure Meyer Terrial Publishers, Montreal 208pp Paper art B.B. King and Dick 2005- Collection of treasures of 12 B.B.King- Treasures Waterman Bulfinch Press 160pp cloth B.B. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Layout 1 (Page 1

In 1949, Janet Collins—the first Black artist to appear Jean-Léon Destiné’s company along with Spanish and African Artists of the African Diaspora on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera—and Jean-Léon Hindu dances. It was a bold move, and its legacy is seen Destiné made their debut appearances at Jacob’s Pillow. today in the all-encompassing dance programming at Famous for his work with Katherine Dunham, Destiné Jacob’s Pillow. In 1970 Ted Shawn presented Dance Theatre and Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival: was the first of many Black artists to teach in The School of Harlem’s first formal “engagement.” Critic Walter Terry American at Jacob’s Pillow in 1949, and returned to direct the praised the company’s debut and Shawn referred to the Inception to Present Cultural Traditions Program in 2004. Over 100 students Dance Theatre of Harlem performance as a “highlight of from around the world attend this professional-track the summer.” School at Jacob’s Pillow each year. f v f Heritage Beginning in the 1980s, African-American companies The ground-breaking Lester Horton Dance Theatre appeared at the Pillow more and more frequently. “Dance includes every way that men of all races in every period of the made its Pillow debut in 1953. Several of its young Highlights since then have included engagements by Participate in African Diaspora activities at JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE members, James Truitte, Carmen de Lavallade, and tappers Savion Glover, Gregory Hines and Jimmy Jacob’s Pillow Dance world’s history have moved rhythmically to express themselves.”—Ted Shawn (1915) Alvin Ailey, would leave a lasting impression on the Slyde, hip-hop from Rennie Harris, and world premiere dance world. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 9 Article 15 2009 Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement Melissa Seifert Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Seifert, Melissa (2009) "Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Seifert: Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in t Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement By: Melissa Seifert The origins of the Black Power Movement can be traced back to the civil rights movement’s sit-ins and freedom rides of the late nineteen fifties which conveyed a new racial consciousness within the black community. The initial forms of popular protest led by Martin Luther King Jr. were generally non-violent. However, by the mid-1960s many blacks were becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow pace and limited extent of progressive change. -

Bridge & Tunnel

March 29 – May 1, 2016 on the Upperstage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts with contributions by Janet Allen Gordon Strain, Katie Cowan Sickmeier, Allen Hahn, Todd Mack Reischman Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON SPONSOR 2015-2016 YOUTH AUDIENCE & MATINEE PROGRAMS SPONSOR 2 INDIANA REPERTORY THEATRE Bridge & Tunnel by Sarah Jones An open-mic poetry night becomes a celebration of American diversity in the Tony Award- winning play, Bridge & Tunnel. Follow along as one woman plays more than a dozen characters of various genders, ages, and nationalities as life stories are shared and dreams are dared. Jones’s script encourages us to look through new eyes at an all-inclusive America: a beautiful ideal for immigrants and nationals alike, where liberty, equality, and opportunity have concrete, vital meaning. Student Matinees at 10:00 A.M. on April 6 & 13 Estimated length: 90 minutes, with no intermission Recommended for grades 11-12 due to strong language and mature themes. Themes & Topics Poetry and Storytelling Race and Nationality Equality and Opportunity Humor and Vulnerability Empathy and Compassion Tradition and Sexuality Immigration Freedom, Fear of Exclusion Multiculturalism Contents Milicent Wright, Actress 3 Executive Artistic Director’s Note 4 Director’s Note 5 Designer Notes 6 Poet & Playwright Sarah Jones 8 Slam Poetry 10 Historic Poets 12 Around the World 14 Academic Standards Alignment Guide 21 Pre-Show Activity 22 Discussion Questions 23 Activities 23 Education Sales Writing Prompts 24 Randy Pease • 317-916-4842 Resources 25 [email protected] Glossary 28 Going to the Theatre 34 Ann Marie Elliott • 317-916-4841 [email protected] cover art by Kyle Ragsdale Outreach Programs Milicent Wright • 317-916-4843 [email protected] INDIANA REPERTORY THEATRE 3 Milicent Wright Actor Characters in the Play: Ms. -

National Conference

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION In Memoriam We honor those members who passed away this last year: Mortimer W. Gamble V Mary Elizabeth “Mery-et” Lescher Martin J. Manning Douglas A. Noverr NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION APRIL 15–18, 2020 Philadelphia Marriott Downtown Philadelphia, PA Lynn Bartholome Executive Director Gloria Pizaña Executive Assistant Robin Hershkowitz Graduate Assistant Bowling Green State University Sandhiya John Editor, Wiley © 2020 Popular Culture Association Additional information about the PCA available at pcaaca.org. Table of Contents President’s Welcome ........................................................................................ 8 Registration and Check-In ............................................................................11 Exhibitors ..........................................................................................................12 Special Meetings and Events .........................................................................13 Area Chairs ......................................................................................................23 Leadership.........................................................................................................36 PCA Endowment ............................................................................................39 Bartholome Award Honoree: Gary Hoppenstand...................................42 Ray and Pat Browne Award