The Tshon Gang in Bon Dzogchen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of the Andes

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2006 Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of the Andes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Capriles, E. (2006). Capriles, E. (2006). Beyond mind II: Further steps to a metatranspersonal philosophy and psychology. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 25(1), 1–44.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 25 (1). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.24972/ijts.2006.25.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of The Andes Mérida, Venezuela Some of Wilber’s “holoarchies” are gradations of being, which he views as truth itself; however, being is delusion, and its gradations are gradations of delusion. Wilber’s supposedly universal ontogenetic holoarchy contradicts all Buddhist Paths, whereas his view of phylogeny contradicts Buddhist Tantra and Dzogchen, which claim delusion/being increase throughout the aeon to finally achieve reductio ad absur- dum. Wilber presents spiritual healing as ascent; Grof and Washburn represent it as descent—yet they are all equally off the mark. -

The Mirror 84 January-February 2007

THE MIRROR Newspaper of the International Dzogchen Community JAN/FEB 2007 • Issue No. 84 NEW GAR IN ROMANIA MERIGAR EAST SUMMER RETREAT WITH CHÖGYAL NAMKHAI NORBU RETREAT OF ZHINE AND LHAGTHONG ACCORDING TO ATIYOGA JULY 14-22, 2007 There is a new Gar in Romania called Merigar East. The land is 4.5 hectares and 600 meters from the Black Sea. The Gar is 250 meters from a main road and 2 kilometers from the nearest village called the 23rd of August (the day of liberation in World War II); it is a 5-minute walk to the train station and a 10-minute walk to the beach. There are small, less costly hotels and pensions and five star hotels in tourist towns and small cities near by. There is access by bus, train and airplane. Inexpensive buses go up and down the coast. There is an airport in Costanza, 1/2 hour from the land, and the capital, Bucharest, 200 kilometers away, offers two international airports. At present we have only the land, but it will be developed. As of January 2007 Romania has joined the European Union. Mark your calendar! The Mirror Staff Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in the Tashigar South Gonpa on his birthday N ZEITZ TO BE IN INSTANT PRESENCE IS TO BE BEYOND TIME The Longsal Ati’i Gongpa Ngotrod In this latest retreat, which was through an intellectual analysis of CHÖGYAL NAMKHAI NORBU Retreat at Tashigar South, Argentina transmitted all around the world by these four, but from a deep under- SCHEDULE December 26, 2006 - January 1, 2007 closed video and audio webcast, standing of the real characteristics thanks to the great efforts and work of our human existence. -

Summer 2018-Summer 2019

# 29 – Summer 2018-Summer 2019 H.H. Lungtok Dawa Dhargyal Rinpoche Enthusiasm in Our Dharma Family CyberSangha Dying with Confidence LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE 2019/29 — CONTENTS GREETINGS 3 Greetings and news from the editors IN THE SPOTLIGHT 4 Five Extraordinary Days at Menri Monastery GOING BEYOND 8 Retreat Program 2019/2020 at Lishu Institute THE SANGHA 9 There Is Much Enthusiasm and Excitement in Our Dharma Family 14 Introducing CyberSangha 15 What's Been Happening in Europe 27 Meditations to Manifest your Positive Qualities 28 Entering into the Light ART IN THE SANGHA 29 Yungdrun Bön Calendar for 2020 30 Powa Retreat, Fall 2018 PREPARING TO DIE 31 Dying with Confidence THE TEACHER AND THE DHARMA 33 Bringing the Bon Teachings into the World 40 Tibetan Yoga for Health & Well-Being 44 Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche's 2019 European Seminars and online Teachings THE LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE is a joint venture of the community of European students of Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. Ideas and contributions are welcome at [email protected]. You can find this and the previous issues at www.ligmincha.eu, and you can find us on the Facebook page of Ligmincha Europe Magazine. Chief editor: Ton Bisscheroux Editors: Jantien Spindler and Regula Franz Editorial assistance: Michaela Clarke and Vickie Walter Proofreaders: Bob Anger, Dana Lloyd Thomas and Lise Brenner Technical assistance: Ligmincha.eu Webmaster Expert Circle Cover layout: Nathalie Arts page Contents 2 GREETINGS AND NEWS FROM THE EDITORS Dear Readers, Dear Practitioners of Bon, It's been a year since we published our last This issue also contains an interview with Rob magazine. -

The Five Elements in Tibetan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen

HEALING WITH FORM, ENERGY AND LIGHT front.p65 1 3/6/2002, 11:21 AM Page ii blank front.p65 2 3/6/2002, 11:21 AM HEALING WITH FORM, ENERGY AND LIGHT The Five Elements in Tibetan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen by Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche Edited by Mark Dahlby Snow Lion Publications Ithaca, NY / Boulder, CO front.p65 3 3/6/2002, 11:21 AM Snow Lion Publications 605 West State Street P.O. Box 6483 Ithaca, NY 14851 607-273-8519 www.snowlionpub.com Copyright © 2002 by Tenzin Wangyal All right reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 1-55939-176-6 Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wangyal, Tenzin. Healing with form, energy and light : the five elements in Tibetan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen / Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55939-176-6 1. Rdzogs-chen (Bonpo). 2. Spiritual life—Bonpo (Sect) 3. Spiritual life—Tantric Buddhism 4. Bonpo (Sect)—Doctrines. I. Title. BQ7982.3. .W345 2002 299’.54—dc21 2002000288 front.p65 4 3/6/2002, 11:21 AM CONTENTS Preface x The Prayer of the Intermediate State xiii Introduction xvii The Bön Religion xix ONE: The Elements 1 Three Levels of Spiritual Practice 3 External 3 Internal 3 Secret 4 Relating to the Sacred 5 The Five Pure Lights 8 The Dissolution of the Elements 11 Understanding Through the Elements 11 Relating Oneself to the Elements 12 Earth 13 Water 15 Fire 16 Air 17 Space 19 The Elements and Our Well-Being 21 How -

13. Tibetan Buddhism.Pdf

Prajïäpäramitä Sütra, Tibetan Manuscript Tibetan Buddhism Çäntideva's Bodhisattva Vow 12. By giving up all, sorrow is transcended And my mind will realize the sorrowless state. [Çäntideva was an 8th century Indian Mahäyäna It is best that I now give all to all beings philosopher of the Mädhyamika school (in the line from In the same way as I shall at death. Nägärjuna). His text, the Bodhicaryävatära (Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life) still exists in Sanskrit and 13. Having given this body up its Tibetan translation is universally used in the practice of For the pleasure of all living beings, Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama regards this text to be By killing, abusing, and beating it of paramount importance. In the film Kundun, about the May they always do as they please. life of the Dalai Lama, we hear these opening verses as the young Dalai Lama is given his first instruction.] 14. Although they may play with my body And make it a thing of ridicule, 8. May I be the doctor and the medicine Because I have given it up to them And may I be the nurse What is the use of holding it dear? For all sick beings in the world Until everyone is healed. 15. Therefore I shall let them do anything to it That does not cause them any harm, 9. May a rain of food and drink descend And when anyone encounters me To clear away the pain of thirst and hunger May it never be meaningless for him. And during the eon of famine May I myself turn into food and drink. -

Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia 12-2.Indd

Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 5/2 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 1 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 2 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 Ethnolinguistics, Sociolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 5, No. 2 Publication of Charles University in Prague Philosophical Faculty, Institute of South and Central Asia Seminar of Mongolian Studies Prague 2012 ISSN 1803–5647 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 3 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 Th is journal is published as a part of the Programme for the Development of Fields of Study at Charles University, Oriental and African Studies, sub-programme “Th e process of transformation in the language and cultural diff erentness of the countries of South and Central Asia”, a project of the Philosophical Faculty, Charles University in Prague. Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 Linguistics, Ethnolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 5, No. 2 (2012) © Editors Editors-in-chief: Jaroslav Vacek and Alena Oberfalzerová Editorial Board: Daniel Berounský (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) Agata Bareja-Starzyńska (University of Warsaw, Poland) Katia Buff etrille (École pratique des Hautes-Études, Paris, France) J. Lubsangdorji (Charles University Prague, Czech Republic) Marie-Dominique Even (Centre National des Recherches Scientifi ques, Paris, France) Marek Mejor (University of Warsaw, Poland) Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Domiin Tömörtogoo (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Reviewed by Prof. Václav Blažek (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic) and Prof. Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) English correction: Dr. -

Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa's Great Perfection Philosophy of Action

Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa's Great Perfection Philosophy of Action The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40050138 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa’s Great Perfection Philosophy of Action A dissertation presented by Adam S. Lobel to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University Cambridge, MA April 2018! ! © 2018, Adam S. Lobel All rights reserved $$!! Advisor: Janet Gyatso Author: Adam S. Lobel Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa’s Great Perfection Philosophy of Action Abstract This is a study of the philosophy of practical action in the Great Perfection poetry and spiritual exercises of the fourteenth century Tibetan author, Longchen Rabjampa Drime Ozer (klong chen rab 'byams pa dri med 'od zer 1308-1364). I inquire into his claim that practices may be completely spontaneous, uncaused, and effortless and what this claim might reveal about the conditions of possibility for action. Although I am interested in how Longchenpa understands spontaneous practices, I also question whether the very categories of practice and theory are useful for interpreting his writings. -

Tenzin Wangyal Youtube Video Resources

Versie 0.1 – 20 Februari 2013 – © KenKon TENZIN WANGYAL YOUTUBE VIDEO RESOURCES UNIFICATION OF THE THREE SPACES Unification of the three spaces part 1/3 Unification of the three spaces part 2/3 Unification of the three spaces part 3/3 FIVEFOLD TEACHINGS OF DAWA GYALTSEN Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 1/8, Introduction Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 2/8, Introduction 2 Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 3/8, Vision is Mind Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 4/8, Mind is Empty Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 5/8, Emptiness is Clear Light Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 6/8, Clear Light is Union Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 7/8, Union is Great Bliss Fivefold teachings of Dawa Gyaltsen, Part 8/8, Conclusion TIBETAN SOUND HEALING Tibetan Sound Healing part 1/5, Introduction Tibetan Sound Healing part 2/5, A Tibetan Sound Healing part 3/5, OM Tibetan Sound Healing part 4/5, HUNG Tibetan Sound Healing part 5/5, RAM Tibetan Sound Healing part 6/6, DZA Tibetan Sound Healing part 7/7, Conclusion Teaser for Tibetan Sound Healing Online Workshop, Changing your Life Through Sound Teaser for Tibetan Sound Healing Online Workshop DREAM YOGA Teaser for Dream Yoga Online Workshop Dream Yoga Versie 0.1 – 20 Februari 2013 – © KenKon AWAKENING THE SECRET BODY Awakening the sacred body (Tibetan Yogas of Breath and Movement), Introduction of book/dvd Awakening the sacred body (Tibetan Yogas of Breath and Movement), Teaser Online Workshop LONG VIDEOS The five elements, guided meditation practice Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche guides a simple meditation practice that can help you to connect intimately with the five natural elements of earth, water, fire, air and space. -

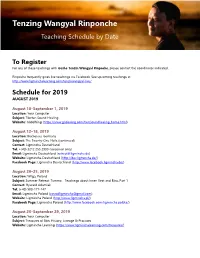

Tenzing Wangyal Rinponche Teaching Schedule by Date

Tenzing Wangyal Rinponche Teaching Schedule by Date To Register For any of these teachings with Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, please contact the coordinator indicated. Rinpoche frequently gives live teachings via Facebook. See upcoming teachings at http://www.ligminchalearning.com/tenzinwangyal-live/. Schedule for 2019 AUGUST 2019 August 10–September 1, 2019 Location: Your Computer Subject: Tibetan Sound Healing Website: GlideWing (https://www.glidewing.com/twr/soundhealing_home.html) August 12–18, 2019 Location: Buchenau, Germany Subject: The Twenty-One Nails (continued) Contact: Ligmincha Deutschland Tel: +(49) 3212 255 2999 (voicemail only) Email: Ligmincha Deutschland ([email protected]) Website: Ligmincha Deutschland (http://dev.ligmincha.de/) Facebook Page: Ligmincha Deutschland (http://www.facebook.ligmincha.de/) August 20–25, 2019 Location: Wilga, Poland Subject: Summer Retreat: Tummo - Teachings about Inner Heat and Bliss, Part 1 Contact: Ryszard Adamiak Tel: (+48) 500-177-147 Email: Ligmincha Poland ([email protected]) Website: Ligmincha Poland (http://www.ligmincha.pl/) Facebook Page: Ligmincha Poland (http://www.facebook.com/ligmincha.polska/) August 23–September 29, 2019 Location: Your Computer Subject: Treasures of Bön: History, Lineage & Practices Website: Ligmincha Learning (https://www.ligminchalearning.com/treasures/) SEPTEMBER 2019 September 6–8, 2019 Location: Budapest, Hungary Subject: Spontaneous Creativity: Meditations for Manifesting Your Positive Qualities Contact: Olivia Zsamboki Email: Ligmincha -

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche Concern Without Panic Week 1: “Facing Fear, Finding Peace” October 3, 2020

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche Concern without Panic Week 1: “Facing Fear, Finding Peace” October 3, 2020 Greetings. My name is Tenzin Wangyal. I'm a Tibetan lama. I was born in India, grew up in a monastery, and received my geshe degree at Menri Monastery in northern India in 1986. The geshe degree is the full training in Buddhist philosophy. After I finished that, I traveled with my teacher, His Eminence Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche. In the last 30 years, I have been teaching in the West. We have established Ligmincha International organization, based in Virginia. We have started more than 35 centers around the world. So I'm very happy and honored to be invited to teach this Tricycle Dharma Talk series. The title of week one of this four-week course will be "Facing Fear, Finding Peace." It's very important to understand our fear when it manifests. The only way to find a deep sense of peace is when you can fully recognize, embrace, accommodate, accept, and transcend your fear. Most of the time in our life, we tend to run away from our fear. We are not able to see, connect with, and transform our fear. So that will be the first week. The second week is titled "Turning Pain into the Path." It's very important to recognize one's suffering and then know what causes the suffering; this is an important teaching in Buddhism; we see this, for example, in the first noble truth. It is similar in the Tibetan tradition we call it taking all our experiences into the path of our enlightenment. -

The Rimé Activities of Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol (1781-1851)1

The Rimé Activities of Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol (1781-1851)1 Rachel H. Pang (Davidson College) on-sectarianism (ris med), especially in the Tibetan Buddhist context, is most often associated with the lives and works of N a group of nineteenth-century religious luminaries from the Kham region of eastern Tibet. Referred to collectively as the “non- sectarian movement” by contemporary scholars, this group consisted of Jamgön Kongtrül, Jamyang Khyentsé Wangpo, Chokgyur Lingpa, Dza Patrul, Ju Mipham, and others.2 Yet, approximately three dec- ades prior to the non-sectarian activities of Jamgön Kongtrül and his contemporaries, there was a figure fervently advocating non- sectarianism in north-eastern, central and western Tibet: the re- nowned poet-saint Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol (1781-1851). While both Tibetan studies scholars and Tibetan Buddhists alike have not- ed Shabkar’s non-sectarian tendencies in general, this topic has re- mained largely unexplored in the scholarly literature. Because Shab- kar’s non-sectarian activities were so prolific, I argue that it is neces- sary to take serious consideration of Shabkar’s non-sectarian activi- ties as a part of the history, nature, and extent of non-sectarianism in Tibetan Buddhist history as a whole. This essay provides a detailed articulation of Shabkar’s non- sectarianism as presented in his two-volume spiritual autobiog- 3 raphy. In this essay, I demonstrate that in his Life, Shabkar portrays 1 I would like to thank V.V. Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche, V. Lama Tashi Dondup, Gyelwé Yongdzin Lama Nyima Rinpoche, Khenpo Chonyi Rangdrol, the sangha of Takmo Lujin monastery, and my teachers and friends from Amdo—without them my fieldwork and study of Shabkar's writings would not have been possi- ble. -

('Phrul 'Khor): Ancient Tibetan Yogic Practices from the Bon Religion and Their Migration Into Contemporary Medical Settings1

BRILL Asian Medicine 3 (2007) 130-155 www.brill.nl/asme Magical Movement ('Phrul 'Khor): Ancient Tibetan Yogic Practices from the Bon Religion and their Migration into Contemporary Medical Settings1 M.A.Chaoul Abstract Magical movement is a distinctive Tibetan yogic practice in which breath and concentration of the mind are integrated as crucial components in conjunction with particular body move ments. Present in all five spiritual traditions of Tibet-though more prevalent in some than in others-it has been part of Tibetan spiritual training since at least the tenth century CE. This report describes some varieties of magical movement, and goes on to examine their application within conventional biomedical settings. In particular, a pilot study of the method's utility in stress-reduction among cancer patients is considered. Keywords Tibet, Bon, magical movement, mind-body practices, integrative medicine, meditation, cancer, rtsa rlung, 'phrul 'khor, Tibetan Yoga Focusing on the magical movement from the ancient Bon Great Complete ness or Dzogchen (rdzogs chen) tradition's Oral Transmission ofZhang Zhung (Zhang zhung snyan rgyud) 2 and its contemporary representatives and lineage- 1 Written in part on the anniversary ofTonpa Shenrab's passing away and enlightenment. 2 Chandra and Namdak 1968. The magical movement chapter is the 'Quintessential Instruc tions of the Oral Wisdom of Magical Movements' ('phrul 'khor zhal shes man ngag, hereafter Quintessential Imtructiom), pp. 631--43. Usually translated as 'Oral Transmission' and lately too as 'Aural Transmission' (Kvaerne 1996, and following him, Rossi 1999). Although I am using 'oral transmission' for snyan rgyud, I find 'aural' or 'listening' to be more accurate renderings of snyan.