Historyofeducati035200mbp.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ulrich's Bimonthly Formerly "Picture of the Month"

The rational, the moral, and the general: an exploration | W. Ulrich | Ul... 1 Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly Formerly "Picture of the Month" September-October 2014 The Rational, the Moral, and the General: An Exploration Part 4: Ideas in Ancient Indian Thought / Introduction HOME An "Eastern" perspective: three ancient Indian ideas In Part 3 of this Previous | Next WER NER ULRICH'S BIO exploration we considered the character of general ideas of reason as ideal For a hyperlinked overview of all issues of "Ulrich's PUBLICATIONS limiting concepts and hence, the need for finding ways to "approximate" Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the Month" series, READINGS ON CSH their intent and to unfold their meaning in real-world contexts of practice. see the site map DOWNLOADS We also considered the eternal tension of the particular (or contextual) and PDF file HARD COPIES the general (or universal) in the quest for such meaning clarification and CRITICAL SYSTEMS described two basic "critical movements of thought" involved, a HEURISTICS (CSH) Note: This is the forth of the essays on the role of general CST FOR PROFESSIONALS contextualizing and a decontextualizing movement. We concluded that the & CITIZENS ideas in rational thought and notion of a cycle of critical contextualization (or "critically contextualist action. With it we begin an A TRIBUTE TO excursion into the world of C.W. CHURCHMAN cycle") might provide an elementary heuristic for reflective and discursive ideas of ancient India, as represented by the Vedic LUG ANO SUMMER SCHOOL processes of "approximation." tradition of thought and esp. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

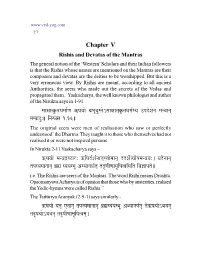

Rishi and Devtas of Vedic Mantra

www.ved-yog.com 52 Chapter V Rishis and Devatas of the Mantras The general notion of the ‘Western’ Scholars and their Indian followers is that the Rishis whose names are mentioned on the Mantras are their composers and devatas are the deities to be worshipped. But this is a very erroneous view. By Rishis are meant, according to all ancient Authorities, the seers who made out the secrets of the Vedas and propagated them. Yaskacharya, the well known philologist and author of the Nirukta.says in 1-91. lk{kkRÏr/kekZ.k _"k;ks cHkwoqLrs·lk{kkr~Ïr/keZH; mins'ksu eU=ku~ lEizknq%µ fu#Dr 1-19µ The original seers were men of realisation who saw or perfectly understood’ the Dharma. They taught it to those who themselves had not realised it or were not inspired persons. In Nirukta 2-11 Yaskacharya says – _"k;ks eU=nz"Vkj% _f"knZ'kZukr~Lrkseku~ nn'ksZR;kSieU;o%A ;nsuku~ riL;ekuku~ czã Lo;EHkw vH;ku'kZr~ rn`.kh.kke`f"kRofefr foKkirsµ i.e. The Rishis are seers of the Mantras. The word Rishi means Drashta. Opaomanyava Acharya is of opinion that those who by austerities, realised the Yedic-hymns were called Rishis.” The Taittiriya Aranyak (2-9-1) says similarly - _"k;ks ;r~ ,uku~ riL;ekuku~ czãLo;EHkw vH;ku"kZr~ rs_"k;ks·Hkou~ rn`"k;ks·Hkou~ rn`"kh.kke`f"kRoe~A www.ved-yog.com 53 Those that after tapas or deep meditation realised the secret meaning of the Vedic Mantras, became Rishis by the Grace of the Almighty. -

A Review on - Amlapitta in Kashyapa Samhita

Original Research Article DOI: 10.18231/2394-2797.2017.0002 A Review on - Amlapitta in Kashyapa Samhita Nilambari L. Darade1, Yawatkar PC2 1PG Student, Dept. of Samhita, 2HOD, Dept. of Samhita & Siddhantha SVNTH’s Ayurved College, Rahuri Factory, Ahmadnagar, Maharashtra *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] Abstract Amlapitta is most common disorders in the society nowadays, due to indulgence in incompatible food habits and activities. In Brihatrayees of Ayurveda, scattered references are only available about Amlapitta. Kashyapa Samhita was the first Samhita which gives a detailed explanation of the disease along with its etiology, signs and symptoms with its treatment protocols. A group of drugs and Pathyas in Amlapitta are explained and shifting of the place is also advised when all the other treatment modalities fail to manage the condition. The present review intended to explore the important aspect of Amlapitta and its management as described in Kashyapa Samhita, which can be helpful to understand the etiopathogenesis of disease with more clarity and ultimately in its management, which is still a challenging task for Ayurveda physician. Keywords: Amlapitta, Dosha, Aushadhi, Drava, Kashyapa Samhita, Agni Introduction Acharya Charaka has not mentioned Amlapitta as a Amlapitta is a disease of Annahava Srotas and is separate disease, but he has given many scattered more common in the present scenario of unhealthy diets references regarding Amlapitta, which are as follow. & regimens. The term Amlapitta is a compound one While explaining the indications of Ashtavidha Ksheera comprising of the words Amla and Pitta out of these, & Kamsa Haritaki, Amlapitta has also been listed and the word Amla is indicative of a property which is Kulattha (Dolichos biflorus Linn.) has been considered organoleptic in nature and identified through the tongue as chief etiological factor of Amlapitta in Agrya while the word Pitta is suggestive of one of the Tridosas Prakarana. -

Study of Caste

H STUDY OF CASTE BY P. LAKSHMI NARASU Author of "The Essence of Buddhism' MADRAS K. V. RAGHAVULU, PUBLISHER, 367, Mint Street. Printed by V. RAMASWAMY SASTRULU & SONS at the " VAVILLA " PRESS, MADRAS—1932. f All Rights Reservtd by th* Author. To SIR PITTI THY AG A ROY A as an expression of friendship and gratitude. FOREWORD. This book is based on arfcioles origiDally contributed to a weekly of Madras devoted to social reform. At the time of their appearance a wish was expressed that they might be given a more permanent form by elaboration into a book. In fulfilment of this wish I have revised those articles and enlarged them with much additional matter. The book makes no pretentions either to erudition or to originality. Though I have not given references, I have laid under contribution much of the literature bearing on the subject of caste. The book is addressed not to savants, but solely to such mea of common sense as have been drawn to consider the ques tion of caste. He who fights social intolerance, slavery and injustice need offer neither substitute nor constructive theory. Caste is a crippli^jg disease. The physicians duty is to guard against diseasb or destroy it. Yet no one considers the work of the physician as negative. The attainment of liberty and justice has always been a negative process. With out rebelling against social institutions and destroying custom there can never be the tree exercise of liberty and justice. A physician can, however, be of no use where there is no vita lity. -

Knowledge and Belief in the Dialogue of Cultures: Russian Philosophical

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IVA, Eastern and Central Europe, Volume 39 General Editor George F. McLean Knowledge and Belief in the Dialogue of Cultures Edited by Marietta Stepanyants Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2011 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Knowledge and belief in the dialogue of cultures / edited by Marietta Stepanyants. p. cm. – (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series IVA, Eastern and Central Europe ; v. 39) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Knowledge, Theory of. 2. Belief and doubt. 3. Faith. 4. Religions. I. Stepaniants, M. T. (Marietta Tigranovna) BD161.K565 2009 2009011488 210–dc22 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-262-2 (paper) TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication v George F. McLean Introduction 1 Marietta Stepanyants Part I. Chinese Thought Chapter I. On Knowing (Zhi): Praxis-Guiding Discourse in 17 the Confucian Analects Henry Rosemont, Jr.. Chapter II. Knowledge/Rationale and Belief/Trustiness in 25 Chinese Philosophy Artiom I. Kobzev Chapter III. Two Kinds of Warrant: A Confucian Response to 55 Plantinga’s Theory of the Knowledge of the Ultimate Peimin Ni Chapter IV. Knowledge as Addiction: A Comparative Analysis 59 Hans-Georg Moeller Part II. Indian Thought Chapter V. Alethic Knowledge: The Basic Features of Classical 71 Indian Epistemology, with Some Comparative Remarks on the Chinese Tradition Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad Chapter VI. The Status of the Veda in the Two Mimansas 89 Michel Hulin Chapter VII. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Balabodha Sangraham

बालबोध सङ्ग्रहः - १ BALABODHA SANGRAHA - 1 A Non-detailed Text book for Vedic Students Compiled with blessings and under instructions and guidance of Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 69th Peethadhipathi and Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Sankara Vijayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 70th Peethadhipathi of Moolamnaya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Offered with devotion and humility by Sri Atma Bodha Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Kumbakonam Swamiji) Disciple of Pujyasri Kuvalayananda Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Tambudu Swamiji) Translation from Tamil by P.R.Kannan, Navi Mumbai Page 1 of 86 Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham ॥ श्रीमहागणपतये नमः ॥ ॥ श्री गु셁भ्यो नमः ॥ INTRODUCTION जगत्कामकलाकारं नािभस्थानं भुवः परम् । पदपस्य कामाक्षयाः महापीठमुपास्महे ॥ सदाििवसमारमभां िंकराचाययमध्यमाम् । ऄस्मदाचाययपययनतां वनदे गु셁परमपराम् ॥ We worship the Mahapitha of Devi Kamakshi‟s lotus feet, the originator of „Kamakala‟ in the world, the supreme navel-spot of the earth. We worship the Guru tradition, starting from Sadasiva, having Sankaracharya in the middle and coming down upto our present Acharya. This book is being published for use of students who join Veda Pathasala for the first year of Vedic studies and specially for those students who are between 7 and 12 years of age. This book is similar to the Non-detailed text books taught in school curriculum. We wish that Veda teachers should teach this book to their Veda students on Anadhyayana days (days on which Vedic teaching is prohibited) or according to their convenience and motivate the students. -

AGH-111 Course Title: Agricultural Heritage Credits: 1(1+0) Course Teacher Prof.Prasad

DEPARTMENT OF AGRONOMY Course No: AGH-111 Course Title: Agricultural Heritage Credits: 1(1+0) Course Teacher Prof.Prasad. M Patil Assistant Professor Department of Agronomy Contact: 7507445546, 9860208251 Email Id:[email protected] Prof.Prasad M.Patil (MSc.Agri, Agronomy) Department of Agronomy 7507445546, 9860208251 [email protected] Chapter-8 Plant production through indigenous traditional knowledge Astronomy -Prediction of Monsoon Rains; Parashara, Varamihira, Panchanga in Comparison to modern methods. Astronomy:-The Path of the sun being a fixed circle among the fixed stars is called ecliptic. 1. Modern scientific knowledge of methods of weather forecasting has originated recently. But ancient indigenous knowledge is unique to our country. 2. India had a glorious scientific and technological tradition in the past. 3. A scientific study of meteorology was made by our ancient astronomers and astrologers. 4. Even today, it is common that village astrologers (pandits) are right in surprisingly high percentage of their weather predications. 5. Meteorology is generally believed to be a new science. It may be new to the west, but not in India, where this science has existed since ancient times. 6. A systematic study of this science was made by our ancient astronomers and astrologers. 7. The rules are simple and costly apparatus are not required. Observations coupled with experience over centuries enhanced to develop meteorology. Prof.Prasad M.Patil (MSc.Agri, Agronomy) Department of Agronomy 7507445546, 9860208251 [email protected] Prediction of Monsoon Rains:- The ancient/indigenous method of weather forecast may be broadly classified into two Categories. 1. Observational Methods:- Atmospheric Changes Boi-indicators Chemical Changes Physical Changes Cloud forms and other sky features 2. -

Interpreting the UPANISHADS

Interpreting the UPANISHADS ANANDA WOOD Modified version 2003 Copyright 1996 by Ananda Wood Published by: Ananda Wood 1A Ashoka 3 Naylor Road Pune 411 001 India Phone (020) 612 0737 Email [email protected] Contents Preface . v ‘This’ and ‘that’ . 1 Consciousness . 6 Consciousness and perception . 11 Creation Underlying reality . 21 Cosmology and experience . 23 Creation from self . 26 The seed of creation . 27 Light from the seed . 29 The basis of experience . 30 Creation through personality . 35 Waking from deep sleep . 48 The creation of appearances . 51 Change and continuity Movement . 59 The continuing background . 60 Objective and subjective . 67 Unchanging self . 68 Continuity . 75 Life Energy . 81 Expression . 82 Learning . 84 The living principle . 89 The impersonal basis of personality ‘Human-ness’ . 93 Universal and individual . 96 Inner light . 103 Underlying consciousness . 104 The unborn source . 108 The unmoved mover . 112 One’s own self . 116 The ‘I’-principle . 117 iv Contents Self Turning back in . 119 Unbodied light . 120 The self in everyone . 135 The rider in a chariot . 138 The enjoyer and the witness . 141 Cleansing the ego . 144 Detachment and non-duality . 146 Happiness Value . 152 Outward desire . 153 Kinds of happiness . 154 One common goal . 158 Love . 160 Desire’s end . 162 Freedom . 163 The ground of all reality . 166 Non-duality . 167 The three states . 169 The divine presence God and self . 176 The rule of light . 181 Teacher and disciple Seeking truth . 195 Not found by speech . 196 Learning from a teacher . 197 Coming home . 198 Scheme of transliteration . 201 List of translated passages . -

Hinduism and Social Work

5 Hinduism and Social Work *Manju Kumar Introduction Hinduism, one of the oldest living religions, with a history stretching from around the second millennium B.C. to the present, is India’s indigenous religious and cultural system. It encompasses a broad spectrum of philosophies ranging from pluralistic theism to absolute monism. Hinduism is not a homogeneous, organized system. It has no founder and no single code of beliefs; it has no central headquarters; it never had any religious organisation that wielded temporal power over its followers. Hinduism does not have a single scripture as the source of its various teachings. It is diverse; no single doctrine (or set of beliefs) can represent its numerous traditions. Nonetheless, the various schools share several basic concepts, which help us to understand how most Hindus see and respond to the world. Ekam Satya Viprah Bahuda Vadanti — “Truth is one; people call it by many names” (Rigveda I 164.46). From fetishism, through polytheism and pantheism to the highest and the noblest concept of Deity and Man in Hinduism the whole gamut of human thought and belief is to be found. Hindu religious life might take the form of devotion to God or gods, the duties of family life, or concentrated meditation. Given all this diversity, it is important to take care when generalizing about “Hinduism” or “Hindu beliefs.” For every class of * Ms. Manju Kumar, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, Delhi University, Delhi. 140 Origin and Development of Social Work in India worshiper and thinker Hinduism makes a provision; herein lies also its great power of assimilation and absorption of schools of philosophy and communities of people, (Theosophy, 1931). -

21. Ramanuja Nutrandhadhi

AmudhanAr’s IrAmAnusa nUtranthAthi Annotated Commentary in English By: "sampradAya prachAra dhurantharar" SrIrangam SrI V. MAdhavakkaNNan Our Sincere Thanks to the following for their contributions to this ebook: Images contribution: Ramanuja Dasargal at www.pbase.com/svami Neduntheru Sri Mukund Srinivasan eBook assembly: sadagopan.org Smt. Kala Lakshminarayanan CONTENTS TITLE PAGE Introduction 1 Paasuram 1 3 Paasuram 2 7 Paasuram 3 10 Paasuram 4 13 Paasuram 5 15 Paasuram 6 17 Paasuram 7 19 Paasuram 8 25 Paasuram 9 28 sadagopan.org Paasuram 10 30 Paasuram 11 33 Paasuram 12 38 Paasuram 13 42 Paasuram 14 45 Paasuram 15 51 Paasuram 16 52 Paasuram 17 57 Paasuram 18 59 Paasuram 19 62 Paasuram 20 65 Paasuram 21 68 Paasuram 22 71 Paasuram 23 74 Paasuram 24 76 Paasuram 25 78 Paasuram 26 81 Paasuram 27 83 CONTENTS CONT’D. TITLE PAGE Paasuram 28 85 Paasuram 29 88 Paasuram 30 90 Paasuram 31 93 Paasuram 32 95 Paasuram 33 97 Paasuram 34 100 Paasuram 35 102 Paasuram 36 105 Paasuram 37 109 Paasuram 38 112 Paasuram 39 115 Paasuram 40 117 Paasuram 41 122 sadagopan.org Paasuram 42 125 Paasuram 43 128 Paasuram 44 134 Paasuram 45 137 Paasuram 46 139 Paasuram 47 144 Paasuram 48 147 Paasuram 49 150 Paasuram 50 153 Paasuram 51 156 Paasuram 52 160 Paasuram 53 162 Paasuram 54 165 CONTENTS CONT’D. TITLE PAGE Paasuram 55 168 Paasuram 56 171 Paasuram 57 174 Paasuram 58 177 Paasuram 59 181 Paasuram 60 184 Paasuram 61 186 Paasuram 62 189 Paasuram 63 192 sadagopan.org Paasuram 64 194 Paasuram 65 197 Paasuram 66 200 Paasuram 67 203 Paasuram 68 207 Paasuram 69 210 Paasuram