The Cotehele Cupboard: an Elegy in Oak. Tina O'connor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIES of the TUDORS the Influence of Margaret Beaufort and Her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership

TIES OF THE TUDORS The Influence of Margaret Beaufort and her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership P.V. Smolders Student Number: 1607022 Research Master Thesis, August 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Liesbeth Geevers Leiden University, Institute for History Ties of the Tudors The Influence of Margaret Beaufort and her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership. Pauline Vera Smolders Student number 1607022 Breestraat 7 / 2311 CG Leiden Tel: 06 50846696 E-mail: [email protected] Research Master Thesis: Europe, 1000-1800 August 2016 Supervisor: Dr. E.M. Geevers Second reader: Prof. Dr. R. Stein Leiden University, Institute for History Cover: Signature of Margaret Beaufort, taken from her first will, 1472. St John’s Archive D56.195, Cambridge University. 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 3 Introduction 4 1 Kinship Networks 11 1.1 The Beaufort Family 14 1.2 Marital Families 18 1.3 The Impact of Widowhood 26 1.4 Conclusion 30 2 Patronage Networks 32 2.1 Margaret’s Household 35 2.2 The Court 39 2.3 The Cambridge Network 45 2.4 Margaret’s Wills 51 2.5 Conclusion 58 3 The Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership 61 3.1 Margaret’s Reputation and the Role of Women 62 3.2 Mother and Son 68 3.3 Preserving Tudor Rulership 73 3.4 Conclusion 76 Conclusion 78 Bibliography 82 Appendixes 88 2 Abbreviations BL British Library CUL Cambridge University Library PRO Public Record Office RP Rotuli Parliamentorum SJC St John’s College Archives 3 Introduction A wife, mother of a king, landowner, and heiress, Margaret of Beaufort was nothing if not a versatile women that has interested historians for centuries. -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Lists of Appointments CHAMBER Administration Lord Chamberlain 1660-1837

Lists of Appointments CHAMBER Administration Lord Chamberlain 1660-1837 According to The Present State of the British Court, The Lord Chamberlain has the Principal Command of all the Kings (or Queens) Servants above Stairs (except in the Bedchamber, which is wholly under the Grooms [sic] of the Stole) who are all Sworn by him, or by his Warrant to the Gentlemen Ushers. He has likewise the Inspection of all the Officers of the Wardrobe of the King=s Houses, and of the removing Wardrobes, Beds, Tents, Revels, Musick, Comedians, Hunting, Messengers, Trumpeters, Drummers, Handicrafts, Artizans, retain=d in the King=s or Queen=s Service; as well as of the Sergeants at Arms, Physicians, Apothecaries, Surgeons, &c. and finally of His Majesty=s Chaplains.1 The lord chamberlain was appointed by the Crown. Until 1783 his entry into office was marked by the reception of a staff; thereafter more usually of a key.2 He was sworn by the vice chamberlain in pursuance of a royal warrant issued for that purpose.3 Wherever possible appointments have been dated by reference to the former event; in other cases by reference to the warrant or certificate of swearing. The remuneration attached to the office consisted of an ancient fee of ,100 and board wages of ,1,100 making a total of ,1,200 a year. The lord chamberlain also received plate worth ,400, livery worth ,66 annually and fees of honour averaging between ,24 and ,48 a year early in the eighteenth century. Shrewsbury received a pension of ,2,000 during his last year of office 1714-15. -

Grenzeloos Actuariaat

grenzeloos actuariaat BRON: WIKIPEDIA grenzeloos actuariaat: voor u geselecteerd uit de buitenlandse bladen q STATE OPENING OF PARLIAMENT In the United Kingdom, the State Opening of Parliament is an the Commons Chamber due to a custom initiated in the seventeenth annual event that marks the commencement of a session of the century. In 1642, King Charles I entered the Commons Chamber and Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is held in the House of Lords attempted to arrest five members. The Speaker famously defied the Chamber, usually in late October or November, or in a General King, refusing to inform him as to where the members were hiding. Election year, when the new Parliament first assembles. In 1974, Ever since that incident, convention has held that the monarch cannot when two General Elections were held, there were two State enter the House of Commons. Once on the Throne, the Queen, wearing Openings. the Imperial State Crown, instructs the house by saying, ‘My Lords, pray be seated’, she then motions the Lord Great Chamberlain to summon the House of Commons. PREPARATION The State Opening is a lavish ceremony. First, the cellars of the Palace SUMMONING OF THE COMMONS of Westminster are searched by the Yeomen of the Guard in order to The Lord Great Chamberlain raises his wand of office to signal to the prevent a modern-day Gunpowder Plot. The Plot of 1605 involved a Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, who has been waiting in the failed attempt by English Catholics to blow up the Houses of Commons lobby. -

Aberystwyth University the Poet As a Healer

Aberystwyth University The Poet as a Healer Huws, Bleddyn Published in: Transactions of the Physicians of Myddfai Society / Trafodion Cymdeithas Meddygon Myddfai Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): Huws, B. (2018). The Poet as a Healer. Transactions of the Physicians of Myddfai Society / Trafodion Cymdeithas Meddygon Myddfai, 2011-2017, 143-149. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 The Poet as a Healer Bleddyn Owen Huws All the quotations in verse apart from one in this paper are inflamed circles that appeared under the children’s armpits in the cywydd meter. For those who are not familiar with that caused them to shout in agony. The black buboes are Welsh poetry, just a brief word of explanation. -

Arthurian Personal Names in Medieval Welsh Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberystwyth Research Portal ʹͲͳͷ Summary The aim of this work is to provide an extensive survey of the Arthurian personal names in the works of Beirdd y Tywysogion (the Poets of the Princes) and Beirdd yr Uchelwyr (the Poets of the Nobility) from c.1100 to c.1525. This work explores how the images of Arthur and other Arthurian characters (Gwenhwyfar, Llachau, Uthr, Eigr, Cai, Bedwyr, Gwalchmai, Melwas, Medrawd, Peredur, Owain, Luned, Geraint, Enid, and finally, Twrch Trwyth) depicted mainly in medieval Welsh prose tales are reflected in the works of poets during that period, traces their developments and changes over time, and, occasionally, has a peep into reminiscences of possible Arthurian tales that are now lost to us, so that readers will see the interaction between the two aspects of middle Welsh literary tradition. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... 3 Bibliographical Abbreviations and Short Titles ....................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1: Possible Sources in Welsh and Latin for the References to Arthur in Medieval Welsh Poetry .............................................................................................. 17 1.1. Arthur in the White Book of Rhydderch and the -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1573

1573 1573 At HAMPTON COURT, Middlesex. Jan 1,Thur New Year gifts. New Year Gift roll is not extant, but Sir Gilbert Dethick, Garter King of Arms, gave the Queen: ‘A Book of all the Knights of the Garter made in the short reign of Richard III’. Also Jan 1: play, by the Children of Windsor Chapel.T also masque: Janus. Eight Januses; eight who present fruit. Revels: ‘going to Windsor about Mr Farrant’s play; gloves for the Children of Windsor two dozen and for masquers 16 pair; a desk for Farrant’s play’; ‘a key for Janus’; ‘fine white lamb to make snowballs eight skins’. Robert Moorer, apothecary, for sugar, musk comfits, corianders, clove comfits, cinnamon comfits, rose water, spice water, ginger comfits. ‘All which served for flakes of ice and hail-stones in the masque of Janus, the rose water sweetened the balls made for snowballs presented to her Majesty by Janus’. Janus: Roman god, facing two ways; Richard Farrant: Master of the Children. Jan 2,Fri new appointment: George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury: Earl Marshal. In overall charge of the College of Arms, succeeding the Duke of Norfolk. Jan 4,Sun play, by the Children of Paul’s.T Revels paid for: ‘two squirts for the play of the Children of Paul’s; the waggoner for carriage of the stuff to Hampton Court’, Jan 4. Jan 6,Tues Earl of Desmond and his brother at Hampton Court. Gerald Fitzgerald, 14th Earl of Desmond (c.1533-1583), known as the Rebel Earl, and his brother Sir John Desmond led a rebellion in Ireland and were in the Tower December 1567-Sept 1570, then in the custody of Warham St Leger, in Kent and Southwark. -

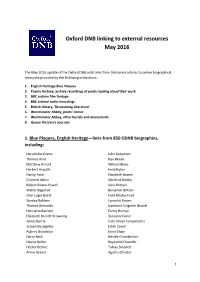

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

Wales and the Wars of the Roses Cambridge University Press C

WALES AND THE WARS OF THE ROSES CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, Manager ILcinfcott: FETTER LANE, E.C. EBmburgfj: 100 PRINCES STREET §& : WALES AND THE WARS OF THE ROSES BY HOWELL T. EVANS, M.A. St John's College, Cambridge Cambridge at the University Press 1915 : £ V*. ©amtrrtrge PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS PREFACE AS its title suggests, the present volume is an attempt to ** examine the struggle between Lancaster and York from the standpoint of Wales and the Marches. Contemporary chroniclers give us vague and fragmentary reports of what happened there, though supplementary sources of informa- tion enable us to piece together a fairly consecutive and intelligible story. From the first battle of St Albans to the accession of Edward IV the centre of gravity of the military situation was in the Marches : Ludlow was the chief seat of the duke of York, and the vast Mortimer estates in mid-Wales his favourite recruiting ground. It was here that he experienced his first serious reverse—at Ludford Bridge; it was here, too, that his son Edward, earl of March, won his way to the throne—at Mortimer's Cross. Further, Henry Tudor landed at Milford Haven, and with a predominantly Welsh army defeated Richard III at Bosworth. For these reasons alone unique interest attaches to Wales and the Marches in this thirty years' war; and it is to be hoped that the investigation will throw some light on much that has hitherto remained obscure. 331684 vi PREFACE I have ventured to use contemporary Welsh poets as authorities ; this has made it necessary to include a chapter on their value as historical evidence. -

The Plantagenet in the Parish: the Burial of Richard III’S Daughter in Medieval London

The Plantagenet in the Parish: The Burial of Richard III’s Daughter in Medieval London CHRISTIAN STEER Westminster Abbey, the necropolis of royalty, is today a centre piece for commemoration. 1 It represents a line of kings, their consorts, children and cousins, their bodies and monuments flanked by those of loyal retainers and officials who had served the Crown. The medieval abbey contained the remains of Edward the Confessor through to Henry VII and was a mausoleum of monarchy. Studies have shown that this was not exclusive: members of the medieval royal family sometimes chose to be buried elsewhere, often in particular religious houses with which they were personally associated.2 Edward IV (d. 1483) was himself buried in his new foundation at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where he was commemorated within his sumptuous chantry chapel.3 But the question of what became of their illegitimate issue has sometimes been less clear. One important royal bastard, Henry Fitz-Roy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset (d. 1536), the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, was buried appropriately with his in-laws, the Howard family in Thetford Priory.4 There is less certainty on the burials of other royal by-blows and the location of one such grave, of Lady Katherine Plantagenet, illegitimate daughter of Richard III, has hitherto remained unknown. This article seeks to correct this. Monuments in Medieval London Few monuments have survived in medieval London. Church rebuilding work during the middle ages, the removal of tombs and the stripping out of the religious houses during the Reformation, together with iconoclasm during the Civil War took their toll on London’s commemorative heritage. -

Records Ofeaylv~ English Dran'ia

volume 21, number 1 (1996) A Newsletter published by REED, University of Toronto, in association with McMaster University. Helen Ostovich, editor Records of Eaylv~ English Dran'ia Contents Patrons and travelling companies in Coventry Elza C . Tiner 1 Correction 38 Announcements 38 ELZA C. TINER Patrons and travelling companies in Coventry The following article provides an index of travelling companies keyed to the REED Coventry collection .' Patrons are listed alphabetically, according to the principal title under which their playing companies and entertainers appear, with cross-references to other titles, if they are also so named in the Records . If a patron's company appears under a title other than the usual or principal one, this other title is in parenthesis next to the description of the company. Companies named according to a patron's civil appointment are indexed under the name of that post as it appears in the Records ; for example, `Lord Chief Justice' and `Sheriff' Following the list of patrons the reader will find an index of companies identified in the Records by their places or origin? The biographical information supplied here has come entirely from printed sources, the chief of which are the following : Acts ofthe Privy Counci4 S .T. Bindoff (ed), The History ofParliament: The House of Commons 1509-1558, 3 vols (London, 1982); Cal- endar of Close Rolls; Calendar ofPatent Rolls (edited through 1582) ; Calendar ofState Papers; C.R. Cheney (ed), Handbook ofDates for Students ofEnglish History ; G.E.C., I The Complete Peerage.. .; The Dictionary ofNational Biography, James E. Doyle, The Official Baronage ofEngland Showing the Succession, Dignities, and Offices ofEvery Peer from 1066 to 1885, 3 vols (London, 1886); PW.