A Contemporary Interpretation of Vernacular Architecture. the Architecture of Nail Çakirhan, Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Home Resort Experience

The Home Resort Experience 2 www.calgazebo.comwww.calgazebo.com Gazebos, Outdoor Rooms & Villas Escape to the secluded sanctuary you’ve always dreamed of - a private tropical oasis, a serene Southern setting, a charming cottage retreat. Whatever your idea of peace and escape may be, Cal Designs provides a relaxing paradise right in the comfort of your own backyard. Step inside any one of our customized Outdoor Rooms and you’ll be instantly transported to a different time and place, secluded from the demands and stresses of everyday life. Create an open-air pavilion for relaxing twilight din- ners; add a fully enclosed Outdoor Room for weekend retreats with the family; or enjoy your own private day spa large enough to house a sauna, hot tub, and changing area. A variety of shapes and sizes also enables you to expand your outdoor living space with versatility - add an outdoor home office, craft room, play house, or pool house. Masterfully crafted from quality materials, all Cal Designs Outdoor Rooms are UBC and IBCO approved. We use only the best components such as premium Redwood, our exclusive maintenance-free Cal Preferred™ synthetic wood, and 30-lb. and 70-lb. live-load roofs. Available in many colors, styles and custom options. Affordability and beauty that perfectly complement your entire outdoor home resort. Experience the quality, style and craftsmanship of Cal Designs outdoor rooms and villas today! Surround Systems Surround yourself in style with a Cal Designs spa surround. Cal Designs Surrounds instantly give your Cal Spas hot tub an elegant face-lift and can be customized to fit any backyard landscape. -

A Guide for Personalizing Your Home

A gude for personalzng your Home Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Importance of Style 7 Chapter 3 Possibilities, Requirements and Limitations 21 Chapter 4 Definition of Terms 61 Appendix A Forms Appendix B List of Acceptable Plants Appendix C List of Prohibited Plants Appendix D Community Association Rules For questons or to submt an applcaton for revew, please contact: Marley Park Communty Assocaton Phone: 623-466-8820 Fax: 623-466-8828 [email protected] Desgn Revew Applcaton forms are also avalable for download at: www.marleypark.net Copyrght © 2006. All Rghts Reserved. Marley Park Communty Assocaton, Inc. 6 April 2009 Page A gude for personalzng your Home Chapter 1 Introducton 6 April 2009 A gude for personalzng your Home Chapter 1 Introduction Welcome to the Neighborhood Neghborhood means sharng smlar feelngs about the place you call home. But t doesn’t mean everyone has to lve n houses that all look the same. Rather than unformty, Marley Park celebrates dversty. The ndvdualty of your home s a vtal component of the unque character of the Marley Park communty. Desgn Revew promotes or establshes communty character by nsurng that certan desgn and archtectural prncples are followed. Ths Gude, and the nformaton contaned wthn, was compled to provde you, the Homeowner, wth easy access to the applcable Desgn Revew gudelnes and procedures. The content of ths document s mportant because t provdes both you and the Desgn Revew Commttee clear drecton and understandng of the expectaton of qualty for Marley Park. It wll also assst you n takng advantage of the opportuntes your Home and Lot provde whle enhancng the overall neghborhood. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Gazebos | Outdoor Living

Bali Huts | Gazebos | Outdoor Living BALI HUTS STARTING FROM $1995 CALL 1300 575 550 FOR A FREE QUOTE FINANCE OPTIONS AVALIABLE 2-10 Rudman Parade, Burleigh Heads, Queensland 4220 About Us 2 With over 35 years of building experience, you are in good hands with us My Name Is Hans Rauch, myself and my wife Sharna run East Coast Bali Huts and Gazebos. You are in good hands when dealing with us, why? Well let me explain further… I have an extensive background in the building and construction trade. I’ve been involved in and managed mostly large projects with extensive landscaping, predominantly in the tropical part of North Queensland, for over 35 years. The Bali Hut being the key factor in many gardens. Be it in a Resort Hotel, Boutique accommodation, a home by the beach/suburbs or on acreage, the Bali Hut comes into its own and is a stellar addition to any garden. Therefore it was a natural progression for me, to become a Bali Hut and Gazebo manufacturer. Why are we here to help you with your new Bali hut? East Coast Bali Huts and Gazebos are here because as we saw, there are so many operators all hiding behind the facts of what you really get for your money with your new Bali hut. “Where is your Bali Hut taking you?” Why East Coast Bali Huts 3 We are the manufacturer of East Coast Bali Huts and Gazebo’s. 100% Australian made and Australian owned. Authentic Alang Alang Bali thatching with cream stitching. Use superior quality timbers. -

Sierra County Visitors Guide May 2013 Aug 17 » Wine in the Woods

2013-2014 Sierra County Visitors Guide www.sierracountychamber.com MAY 2013 Aug 17 » Wine in the Woods. Wine Tasting, Oct 20 » Loyalton Farmer’s Market & Bazaar. Memorial Day Weekend » Kentucky Mine hors d’oeuvres & silent auction at The Gallery, Noon–3 PM; 993-4488 Museum opens. Sierra City. 862-1310 Mountain Creek Restaurant, Old Sierra City Hotel & Sorracco’s Saloon, Sierra City. Tickets pre-sale Oct 31 » Sierra City Trick or Treat Main Street or at the door. 862-9009 or 862-1560 Bring family & friends, bags & buckets & trick JUNE 2013 or treat all along Main Street. 5:30–7:30 PM Main June 15 » Tour de Manure, 62 Mile Valley Bicycle Aug 18 » Loyalton Farmer’s Market & Bazaar. Street Sierra City. 862-1580 race. Sierraville. 994-3344 Noon–3 PM; 993-4488 NoVEMBER 2013 June 15–16 » Underground Gold Miner Museum Aug 24 » E.C.V. Fall Doins. Convention & Nov 9 » Jolly Holiday Bazaar. 9 AM–3 PM Gold Show. Alleghany. 287-3223 Annual Meeting. Tin Cup Diggins, Downieville. Community Hall. Sierra City. 862-1580 www.downie1849.com June 15–16 » Historical Walking Tours of Nov 11 » E.C.V. Candle Light Doins. Grandiose Alleghany. 11am & 2pm. Alleghany. 287-3223 Aug 24 » Native Daughter’s Ice Cream Social. Evening Initiation for gentlemen over 50. Main Sample homemade ice cream & vote on your Street, Downieville. www.downie1849.com June 16 » Father’s Day Fishing Derby. Yuba & favorite. Cookies. Raffle. Noon.320 Commercial Downie rivers. Downieville. 289-3595 St., Downieville. Nov 11 » Veterans’ Day Ceremony. Evening Initiation f. Bell Tower, Downieville. -

Maidencombe Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Maidencombe Conservation Area Character Appraisal MARCH 2005 MAIDENCOMBE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Revised Hal Bishop BA MA Cert Ecol & Cons July 2005 TORBAY COUNCIL Initial research by John Fisher BA MA MRTPI IHBC November 2000 CONTENTS PAGE 1. Location and Essential Characteristics 2 2 Historic Environment, Origins and Development 2 3 Plan Form and Building Types 3 4 Architectural and Historic Qualities 4 4.1 Listed & Other Key Buildings 4.2 Building Form, Ornament & Use of Materials 4.3 Condition of Buildings 5 Character and Relationship of Space 6 6. Green Landscape and Trees 6 7 The Setting and Features of Special Importance 7 8 Extent of Loss, Damage and Intrusion 7 9 Summary 8 Bibliography 9 PHOTOGRAPHS EARLY EDITION ORDNANCE SURVEY: Ordnance Survey First Edition 1:10560 scale 1864 1: 2500 scale maps (not to scale) - Ordnance Survey County Series First Edition surveyed 1862-87 - Ordnance Survey County Series Second Edition surveyed 1904 - Ordnance Survey County Series Third Edition surveyed 1933 APPRAISAL MAPS - Map One: Historic Buildings - Map Two: Age of Buildings - Map Three: Building Materials - Roofs - Map Four Building Materials - Walls - Map Five Important Features 1 Maidencombe Conservation Area Character Appraisal adopted 2 August 2005 1 LOCATION AND ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS 1.1 The conservation area is located about 4½ km north of Torquay town centre and includes two distinct areas of earlier development. The original settlement and historic hamlet, is mostly grouped around Rock House Lane and Steep Hill. West of the historic centre, near the hilltop, and close by the A 379 (the Torquay-Teignmouth Road) are a scattering of 19th century villas in landscaped grounds. -

PERGOLAS 44 Design a Wood Pavilion 8 Urbana Vinyl Pergola

p e r g o l a s pav i l i o n s g a z e b o s 1 1 1 Contents 3 Living Our Values 36 Vinyl Pavilion Gallery 4 It’s Your Choice 38 Wood Pavilion Gallery 42 Design a Vinyl Pavilion PERGOLAS 44 Design a Wood Pavilion 8 Urbana Vinyl Pergola 10 Outback Wood Pergola GAZEBOS 12 Mendoza Wood Pergola 48 Vinyl Octagon Gazebo 14 Riviera Wood Pergola 50 Vinyl Oblong Gazebo 16 Alcove Wood Pergola 52 Vinyl Rectangular Gazebo 18 Vinyl Pergola Gallery 54 Wood Octagon Gazebo 20 Wood Pergola Gallery 56 Wood Oblong Gazebo 22 Design a Vinyl Pergola 58 Wood Rectangular Gazebo 23 Design a Wood Pergola 60 Gazebo Gallery 62 Vinyl Gazebo Standard Features PAVILIONS 63 Wood Gazebo Standard Features 26 Victoria Vinyl Pavilion 64 Design a Gazebo 28 Hampton Wood Pavilion 66 Accessories 30 Cascade Wood Pavilion 32 Breckenridge Wood Pavilion 34 Prairie Wood Pavilion Kit 2 Living Our Values At Berlin Gardens, our first goal is to bring honor and glory to our creator God in everything we do. We do this by manufacturing the highest quality products, delivering our products on time and going beyond your expectations with our customer service. All of this starts by living by our Core Values of honesty, efficiency, attitude, respect and trust. We not only say this, but we believe it. We hope our products help you take life outdoors™. –The Yoder Family 2 It’s Your Choice Classic, Carefree Vinyl Durable and beautiful, vinyl requires very little attention. Regular cleaning with a mild dish detergent or similar product is normally all that’s required to keep your structure looking its best. -

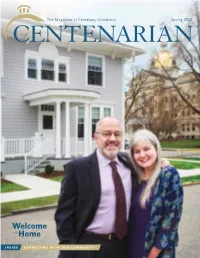

Spring 2018 CENTENARIAN

The Magazine of Centenary University Spring 2018 CENTENARIAN Welcome Home INSIDE CONNECTING WITH OUR COMMUNITY THE MOMENT GREAT SPORTS IN THIS ISSUE DEPARTMENTS University News...2 Advancement...14 Athletics...16 Class News and Notes...18 Meet the Centenarians...24 FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE 10. Community Connection New partnerships are building stronger relationships between Centenary and the community. 12. Q&A with Lisa Baldwin The presidential spouse reflects on her role as an ambassador for Centenary University. 14. Game On! With contributions of more than $750,000, Our Diamond of Dreams has completed its first phase of fundraising. ON THE COVER Welcome Home The newly rebuilt President’s House is officially open for business. HOW TO REACH US Editorial Offices E-mail: Tracey.Thompson@ Sports management majors received CentenaryUniversity.edu career advice from the pros at the seventh (908) 852-1400, ext. 2238 annual Centenary University Sports Editorial & Design Services Management Conference, held in the David Erbach Communications Group and Carol Lackland Center in April. Fifteen /centenaryuniversity sports management alumni joined other professionals to share their experience. Fred @Centenary_NJ Mangione ’93, a senior vice president with /edu/centenary- university-18854 the New York Jets, delivered the keynote. Read more about the conference on page 19. @centenaryuniversity Fred Mangione ’93, senior vice president of the New York Jets WELCOME new executive team to lead us toward a brighter future, and we now have a five-year action plan for assuring our financial sustainability. My leadership team’s dedication has allowed me to shift some of my attention away from day-to-day management toward issues of organizational health, leadership and advocacy for Centenary in many arenas, from the local to the national. -

Untamed Iceland

Untamed Iceland YOUR DETAILED ITINERARY BEGIN YOUR ADVENTURE WITH AN OPTIONAL PRE-TRIP EXTENSION 3 nights in Westman Islands: Volcanic Landscapes & Puffins Day 1 Depart U.S. Day 4 Storhofdi hike • Boat tour • Explore Westman Island Day 2 Arrive in Reykjavik • Ferry to Westman Islands Day 5 Ferry to Landeyjahofn Harbour • Overland to Selfoss • Join main trip Day 3 Explore Heimaey • Local entertainment Day 1 Depart U.S. who do not reserve airfare with us will have their temperature checked upon arrival at the Afternoon/Evening: You’ll fly overnight from hotel. You will then be escorted to your hotel the U.S. to Reykjavik, Iceland. in Selfoss by private car in groups of 1-2 or by private minivan in groups of 3-4, depending on Day 2 Arrive Reykjavik, Iceland • Overland the number of travelers who arrived with you. to Selfoss The transfer is approximately 1 hour and 20 • Destination: Selfoss minutes, depending on traffic. • Included Meals: Breakfast, Dinner Upon arrival in Selfoss, we’ll check in and • Accommodations: Hotel Selfoss or similar receive our room assignments. Depending Breakfast: Served at the hotel beginning at on where we stay, the hotel may feature a 9:30am, featuring international options. restaurant and bar. Typical room amenities may include wireless Internet, flat-screen Morning: You’ll arrive in Reykjavik sometime TVs, minibars, private bath and tea- and in the early to late morning, depending on your coffee-making facilities. You’ll have some specific flight arrangements. Upon arrival, free time to settle in and unpack. Selfoss is the expect to spend about 45 minutes clearing largest town in South Iceland and the gateway customs and completing any health guidelines to all that this area of rich farmland and natural your airline requires. -

Homes in the Dunes, Designed to Preserve

HOMES IN THE DUNES Designed to Preserve HOMES IN THE DUNES Designed to Preserve INTRODUCTION 1 GUIDELINES & SUGGESTIONS Building Location 2 Driveways 3 Building Design 4 Landscaping 6 Terrain Changes 8 Best Practices 8 AWARDS CRITERIA 9 AWARDED PROJECTS 9 DESIGN JURY 13 SCIENTIFIC PANEL 13 INDEX OF PROJECTS 13 Charles F. Davis, III & Marcy Colclough - September 2012 Preserve the Dunes, Inc. P. O. Box 164 Coloma, MI 49084 INTRODUCTION Michigan’s coastal dunes are valued as the beautiful backdrop for The sand dunes are valued by many for their aestheti- the Great Lakes, for the ecological communities they support, cally pleasing backdrop to the lakeshore, for the eco- and their recreational potential. Ideally, development within the logical communities which they support, and for the dunes should enhance individual enjoyment of these areas while recreational potential they provide. No one knows simultaneously protecting the natural resource assets for future this better than those that live and vacation within generations. the coastal dune communities on the west coast of Michigan. Many agree that there is no better place to visit or live than the coastal dunes of Michigan. This has created increasing pressure on Yet it is this desire to live, work and play in the sand the coastal environment from more construction, greater residen- dunes that have slowly degraded natural communities, tial density, larger and larger houses and more extensive use of the altered topography and even destroyed these unique dunes. features. To make matters worse, very often during site planning, home The complex and interactant series of events that design and landscaping little thought is given to how development created the largest of these sand dunes do not ex- in the dunes can impair this fragile environment, such as: ist today, and once lost, these dunes may never be replaced. -

Shed, Gazebo, Cabana & Awning Application & Policy

WORK CANNOT BEGIN ON THE PROJECT UNTIL AFTER APPROVED BY THE ECC - $50 Review Fee SHED, GAZEBO, CABANA & AWNING APPLICATION & POLICY Property Owners Name: ______________________________________________________UBL#:_____________________ Phone: ________________________________________ Email: _______________________________________________ Project Address: ______________________________________________________________________________________ Mailing Address (if different):____________________________________________________________________________ Contractor Name: ________________________________________License#:________________ Phone: ______________ Who will do the work: _____________________________________________ Phone, if different:____________________ Lot type (circle all applicable) INTERIOR CORNER LAKE FRONT GOLF COURSE SEWER SEPTIC LOCATION, DESIGN, MATERIALS, AND COLORS MUST BE COMPATIBLE WITH THE DESIGN OF THE EXTERIOR OF THE RESIDENCE AND FIT IN WITH THE NEIGHBORING SURROUNDINGS. Circle Yes or No to each of the following questions: 1. Is shed, gazebo, cabana or awning pre-manufactured? YES NO a. If the answer is yes, a manufacturers brochure must be included 2. Does the plot plan include: a. Location and Dimensions of the shed. YES NO b. Front, rear, sides and rear set-backs clearly marked? YES NO c. All easements of record? YES NO 3. Does construction require a variance? YES NO 4. Do plans include building specifications, dimensions and elevations? YES NO 5. If trees are being considered for removal, are they tagged and identified by size and number? YES NO 6. Do plans include how building will be anchored? YES NO 7. Do plans show roof pitch(s) and overhang size? YES NO Base Color Trim Color Roof Sample Property Owners Signature: Date: I, the undersigned, have read and understand Article IX, Section 1, of the HVLA CC&R’s, the attached Shed, Gazebo, Policy Rules, as adopted by the Board of Directors and hereby agree to comply with same. -

Annual Report 2018/19

BRANSCOMBE PARISH COUNCIL Clerk to the Council & Responsible Finance Officer: Mrs Nicky A. Langley Higher House Farm Branscombe EX12 3BH 01297 680364 / 07903 080411 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.branscombe-pc.org.uk ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 Page 1 of 9 Activity Report for Branscombe Parish Council 2018/2019 Branscombe Parish Council has had an active year with the successful cumulation of many projects started in previous years. A summary of the highlights is given in the table below. Item Description Police and Crime Report With thanks to Devon & Cornwall Police for their regular attendance and support (see report below). Devon and Cornwall Police regularly attend the Village Hall on a Wednesday afternoon when the Post Office is open, giving residents and businesses the opportunity to Have Your Say and discuss any relevant issues with them. National Trust Allotments The Council have cancelled the lease for the Allotments at Great Seaside as they were not being utilised by members of the Parish. The clean-up prior to return was performed by Councillors and other volunteers, and was accredited by the Great British Spring Clean campaign. Garden and Bench at The Fountain The garden at The Fountain Head Car Park on Berry Hill is regularly maintained by Parish Head Councillors. Unfortunately, after detailed investigations it was found not possible to utilise the existing telephone box as a public Wi-Fi access point, so it will be decommissioned by BT. Devon Air Ambulance Night Landing The Parish Council is working with Devon Air Ambulance (DAA), the Village Hall Committee and Site the Cricket Club to provide a night landing site on the cricket field to the rear of the Village Hall.