Apxeion Oikonomikh™ I™Topia™ Archives of Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Up-To-The-Minute Market Report: Market and Submission Trends in Children’S Publishing

UP-TO-THE-MINUTE MARKET REPORT: MARKET AND SUBMISSION TRENDS IN CHILDREN’S PUBLISHING Prepared for SCBWI Summer Spectacular – August 1, 2020 by Deborah Halverson A snapshot of the current acquisitions environment in children’s publishing, including the effects of the pandemic on market trends and submission and acquisitions trends in publishing houses and literary agencies. reating a snapshot of an industry as rich as children’s publishing is always an ambitious task. Doing so during a pandemic and a major C national cultural movement feels Herculean. Nonetheless, it is a task worthy of attempt. Writers and illustrators create books with publication in mind, if not centrally so, and understanding the marketplace and industry in which they strive for publication is important. I interviewed a dozen professionals across the industry—agents and editors, plus experts in marketing, supply chain, and statistical analysis. All told me, in one form or another, that the current health of our industry is “a mixed bag,” and that the industry will never be the same, in ways both good and bad. To a person, they all believe this industry—which has proven resilient through difficult times as recently as 2008’s Great Recession, and with its audience of young people turning to books for comfort, inspiration, entertainment, and enlightenment—is as essential as ever. This Market Re- port looks at that mixed bag, humbly offering a snapshot of where we are now, four-and-a-half months into the U.S.’s engagement with the pandemic. There will be shades of our pre-pandemic 2019 industry herein, and informed musings about an admittedly unpredictable future. -

Participating Publishers List

Annual Copyright License for Academic Institutions Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at www.copyright.com/academic to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Allen D. Bragdon, Publishers, Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Allerton Press Inc. A M Benjamin Services Allied Academies AACC International Alloy Education AACECorp, Inc. Allured Publishing Corporation Aavia Publishing, LLC Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc. ABC-Clio Inc. ALM Media Properties, LLC ABDO Publishing Group Alphamed Press, Inc. Abingdon Press Alta Metallurgical Services Academy of General Dentistry Altamira Press Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Am Alliance For Health Phys Ed, Recreation & Dance Academy of Management (NY) Am College Of Chest Physicians Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology Am Production and Inventory Control Society Access Intelligence LLC (MD) Am Society for Heating Refrigerating & A C Engineers ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Am Society for Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutic ADA Publishing Co., Inc. AMACOM Books Adis Data Information BV American Academy of Audiology Adler and Adler Publishers Inc. American Academy of Family Physicians Advanstar Communications Inc. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Advantage Business Media American Academy of Pediatrics - Journals Advertising Educational Foundation American Alliance for Theatre and Education Aerospace Medical Association -

15Aprhoddercat Autumn21 FO

FICTION 3 CRIME & THRILLERS 35 NON-FICTION 65 CORONET 91 HODDER STUDIO 99 YELLOW KITE & LIFESTYLE 117 sales information 136 FICTION N @hodderbooks M HodderBooks [ @hodderbooks July 2021 Romantic Comedy . Contemporary . Holiday WELCOME TO FERRY LANE MARKET Ferry Lane Market Book 1 Nicola May Internationally bestselling phenomenon Nicola May is back with a brand new series. Thirty-three-year-old Kara Moon has worked on the market’s flower stall ever since leaving school, dreaming of bigger things. When her good-for-nothing boyfriend cheats on her and steals her life savings, she finally dumps him and rents out her spare room as an Airbnb. Then an anonymous postcard arrives, along with a plane ticket to New York. And there begins the first of three trips of a lifetime, during which she will learn important lessons about herself, her life and what she wants from it – and perhaps find love along the way. Nicola May is a rom-com superstar. She is the author of a dozen novels, all of which have appeared in the Kindle bestseller charts. The Corner Shop in Cockleberry Bay spent 11 weeks at the top of the Kindle bestseller chart and was the overall best-selling fiction ebook of 2019 across the whole UK market. Her books have been translated into 12 languages. 9781529346442 • £7.99 Exclusive territories: Publicity contact: Rebecca Mundy B format Paperback • 384pp World English Language Advance book proofs available on request eBook: 9781529346459 • £7.99 US Rights: Hodder & Stoughton Author lives in Ascot, Berkshire. Author Audio download: Translation Rights: is available for: interview, features, 9781529346466 • £19.99 Lorella Belli, LBLA festival appearances, local events. -

TLJ Spring 2015

a loss beyond words. Your school library, your community. School libraries are much more than literacy centers. They serve as a safe environment to explore and learn, access new information technologies, and collaborate with peers. When a school library program is destroyed by a natural disaster, the students and the community feel the immediate loss of a valuable resource that reaches far beyond books. Since 2006, the American Association of School Librarians, with funding from the Dollar General Literacy Foundation, has given more than 1.5 million dollars in grants to over 150 school libraries across the country affected by natural disasters. APPLY TODAY FOR A BEYOND WORDS GRANT: WWW.ALA.ORG/AASL/ DISASTERRELIEF TEXAS LIBRARY JOURNAL contents Volume 91, No 1 Spring 2015 Published by the TEXAS LIBRARY ASSOCIATION President’s Letter: TLA by the Numbers .....................................................................3 Sharon Amastae Membership in TLA is open to any Guest Editorial: School Librarians Are Teachers First .............................................. 4 individual or institution interested Dorcas Hand, Susi Grissom, and Julie Briggs in Texas libraries. Toolkit for School Administrators-Hiring and Retaining Librarians ...........................6 To find out more about TLA, order TLA Terry Roper and Maria Elena Ovalle publications, or place advertising in Policy Revolution! An Initiative for Libraries in America .......................................... 11 Texas Library Journal, write to A Project of the American Library Association Texas Library Association 3355 Bee Cave Road, Suite 401 Summer Reading Program Collaboration: An Outstanding Austin, Texas 78746-6763; Opportunity for a Public Library, School Library, call 1-800-580-2TLA (2852); or visit and University Course Partnership .......................................................................... 17 our website at www.txla.org. -

2015JCEA Panf.Pdf

本 部: 〒248-0027 神奈川県鎌倉市笛田5-19-9 TEL.0467-38-1590 FAX.0467-38-1591 E-mail. [email protected] Address: 5-19-9 Fueda, Kamakura, Kanagawa 248-0027, Japan TEL: +81 467 38 1590 FAX: +81 467 38 1591 e-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.jcea.info 大切にします。 個人情報 100020141026 Overview 『公正な利用』と『保護』の両立をめざして Aiming at coexistence of "the fair use" and "the protection" 歴史的視点から著作権保護を見ますと海外に Copyright protection first became an issue おいては、15世紀のグーテンベルグによる活版印 overseas in the 15th century with the invention of Gutenberg's letterpress machine. In Japan, a 刷機の発明に始まるといわれています。我が国で Bakufu (shogunate) system of exercising strict は、江戸時代から重板(海賊版)を取り締まる幕 control on "Juhan" (pirated copies) seems to 府の制度が設けられてはいたようですが、法律と have started in the Edo period (1683 - 1868), but しては1 8 6 9(明 治2)年に「出版 条 例 」ができたの the adoption of a Publication Ordinance as a law が著作権制度の始まりといえます。その後、1899 in 1869 is said to formally mark the beginning of (明治32)年に新聞、写真、楽譜、脚本などそれま the Japanese copyright system. Later in 1899, the で個別に定められていた法律を統合した「著作 Copyright Law was enacted, combining the 権法」が誕生し、著作権の国際条約であるベル separate laws that had thus far been established to govern newspapers, photos, music, and books. ヌ条約を締結しました。更に1970(昭和45)年に This was a result of the Berne Convention, an 現在の著作権法が制定されました。 international copyright treaty. The current copyright law was enacted in 1970. 近年では、2002(平成14)年に知的財産基本 法が制定され、知財分野での国際保護と競争力 The Intellectual Property Basic Law was の強化を国策として推進することが謳われていま enacted in 2002, advocating the adoption of す。 national policies aimed at promoting international protection in the intellectual property field and strengthening competitiveness. 『文化的所産の公正な利用に留意しつつ、 著作者等の権利の保護を図り、 "The purpose of this Law is .. -

Preface to the Special Issue

Society and Economy 40 (2018) S1, pp. 1–3 DOI: 10.1556/204.2018.40.S1.1 PREFACE TO THE SPECIAL ISSUE If you type the term “future” into your internet search engine, you will immedi- ately and surely get more than two billion results. Just as the future has penetrated the vast ocean of digital data, it has also become the context of our present social existence, embedded in the domineering narrative of progress and innovation. Evolving beyond its original reference to a date in time further away from the lived moment, the future has come to represent a registry of our contemporary longings and fears. It has turned into a complex concept to be “formed” and “pursued,” an attitude to be “grown” and “groomed,” an intellectual stance with which to view the world. The operations, policies and strategies of both states and institutions cannot be decided without having a future perspective to manage risk and change. Economic-technological-cultural futures do count and are accounted for, are sought and foreseen, cast and forecast; namely, they are acknowledged as necessary elements of professional and academic discourses. This special issue of Society and Economy, entitled “Social Futuring,” howev- er, does not aim to contribute further to the scholarly contemplations about what the future can and will be, or how it will unfold. The papers in this volume rather endeavor to open up a new avenue for thinking and acting – be this academic or lay – concerning our prosperous future(s). Let us start with the title itself. The term social futuring labels a concept and a project launched by the Social Futur- ing Center (SFC) of Corvinus University of Budapest (CUB). -

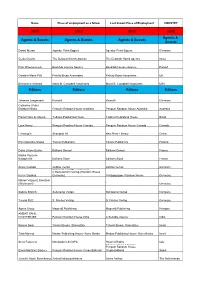

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

On Becoming a Leader.Pdf

0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page i More praise for On Becoming a Leader “Warren Bennis—master practitioner, researcher, and theoretician all in one—has managed to create a practical primer for leaders without sacrificing an iota of necessary subtlety and complexity. No topic is more important; no more able and caring person has attacked it.” —Tom Peters “The lessons here are crisp and persuasive.” —Fortune “This is Warren Bennis’s most important book.” —Peter Drucker “A joy to read...studded with gems of insight.” —Dallas Times-Herald “Bennis identifies the key ingredients of leadership success and offers a game plan for cultivating those qualities.” —Success “Clearly Bennis’s best work in a long line of impressive, significant contributions.” —Business Forum “Totally intriguing, thought-stretching insights into the clockworks of leaders. Bennis has masterfully peeled the onion to reveal the heartseed of leadership. Read it and reap.” —Harvey B. McKay “Warren Bennis gets to the heart of leadership, to the essence of integrity, authenticity, and vision that can never be pinned down to a manipulative formula. This book can help any of us select the new leaders we so urgently need.” —Betty Friedan “Warren Bennis’s insight and his gift with words make these lessons, from some of America’s most interesting leaders, compelling reading for every executive.” —Charles Handy 0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page ii This page intentionally left blank 0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page -

The Enemy at the Gate Habsburgs, Ottomans and the Battle for Europe

046501374-text.qxd:Layout 1 2/17/09 11:06 AM Page iii The Enemy at the Gate Habsburgs, Ottomans and the Battle for Europe ANDREW WHEATCROFT A MEMBER OF THE PERSEUS BOOKS GROUP NEW YORK 046501374-text.qxd:Layout 1 2/17/09 11:06 AM Page iv Copyright © 2008 by Andrew Wheatcroft Published in the United State 2009 by Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group Published in Great Britain 2008 by The Bodley Head, Random House Extracts for T.S. Eliot’s “Little Giddling” and “The Dry Salvages” reproduced by kind permission of the Estate of T.S. Eliot and Faber and Faber Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016-8810. Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail [email protected]. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. LCCN: 2008938931 ISBN-13: 978-0-465-01374-6 British ISBN: 9780224073646 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 046501374-text.qxd:Layout 1 2/17/09 11:06 AM Page v For Denise Gurney Wheatcroft 1914–2007 Mutter, du machtest ihn klein, du warsts, die ihn anfing; dir war er neu, du beugtest über die neuen Augen die freundliche Welt und wehrtest der fremden. -

Publishers Signed up with PLS, As of 1St January 2017

Publishers signed up with PLS, as of 1st January 2017 2000 BC Publishing Limited 2Simple Software Limited 3P Learning Limited 4SM NI Limited 55 North Limited 5M Enterprises Limited 69 Magazine Limited A & N Media Finance Services Limited A and A Thorpe A to B Magazines AA Publishing aa42 AAVO On Camera Publications AB Academic Publishers Abacus Educational Services ABCO Design Limited Aberdeen and Grampian Chamber of Commerce Limited Aberdeen City Council Aberdeen Petroleum Publishing Limited Aberdeen University Press Limited Aberystwyth University Ablan Publishing Company Limited ABR Company Limited Abson Books Abundant Life Recording and Entertainment Company Limited Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited Academy of Ideas Limited Acair Limited ACAS (Advisory, Conciliation & Arbitration Service) ACC Art Books Limited Accelerated Learning Systems Limited Accent Press Limited Access Press UK Accordia Research Institute Accounts Commission ACE Education Advice CIC Limited Aceville Publications Limited ACO Media Limited ACP Publishers Limited ACT (Administration) Limited ACT Publishing UK Limited Action Against Medical Accidents Limited Action Aid Action For Sick Children Action with Communities in Rural England Action Words Active Magazines Limited Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists Limited Adamson Publishing Limited Addiction Recovery Foundation Adrenaline Media Limited Adrian Webster Limited Advance Materials Limited Advanced Success Limited Advanstar Communications (UK) Limited Advantage Publishing -

REFERENCE DOCUMENT Containing the Annual Financial Report

REFERENCE DOCUMENT containing the Annual Financial Report FISCAL YEAR 2017 PROFILE The Lagardère group is a global leader in content publishing, production, broadcasting and distribution, whose powerful brands leverage its virtual and physical networks to attract and enjoy qualifi ed audiences. The Group’s business model relies on creating a lasting and exclusive relationship between the content it offers and its customers. It is structured around four business divisions: • Books and e-Books: Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion, and Foodservice: Lagardère Travel Retail • Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage: Lagardère Active • Sponsorship, Content, Consulting, Events, Athletes, Stadiums, Shows, Venues and Artists: Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945: at the end of World 1986: Hachette regains 26 March 2003: War II, Marcel Chassagny founds control of Europe 1. Arnaud Lagardère is Matra (Mécanique Aviation appointed Managing Partner TRAction), a company focused 10 February 1988: of Lagardère SCA. on the defence industry. Matra is privatised. 2004: the Group acquires 1963: Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 December 1992: a portion of Vivendi Universal becomes Chief Executive Publishing’s French and following the failure of French Offi cer of Matra, which Spanish assets. television channel La Cinq, has diversifi ed into aerospace Hachette is merged into Matra and automobiles. to form Matra-Hachette, and 2007: the Group reorganises Lagardère Groupe, a French around four major institutional 1974: Sylvain Floirat asks partnership limited by shares, brands: Lagardère Publishing, Jean-Luc Lagardère to head is created as the umbrella Lagardère Services (which the Europe 1 radio network. company for the entire became Lagardère Travel Retail ensemble. -

Download Spring 2012

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta SPRING SUMMER 2012 Winter 2012 JEANETTE WINTERSON BACKLIST To coincide with the publication of Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Grove Press has commissioned new artwork by award-winning illustrator Olaf Hajek for the best-selling Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, The Passion, and Sexing the Cherry. Sexing the Cherry (978-0-8021-3578-0 • $14.95 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9870-9 The Passion (978-0-8021-3522-3 • $14.95 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-8021-9871-6 Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (978-0-8021-3516-2 • $14.95 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9872-3 MARCH 2012 “A highly unusual, scrupulously honest, and endearing memoir.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review) Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (978-0-8021-2010-6 • $25.00 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9475-6 GROVE PRESS HARDCOVERS APRIL From the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award–winning author of the best-selling novel Man Gone Down comes a deeply personal, explosive memoir told through the stories of four generations of black American men in one family THE BROKEN KING A Memoir Michael Thomas Man Gone Down was: • One of The New York Times Book Review’s Ten Best Books eviewed on the cover of The New York Times Book Review and chosen of the Year as one of their Ten Best Books of 2008 before winning the IMPAC • Winner of the International R Dublin Literary Award, Man Gone Down introduced a new writer of IMPAC Dublin Literary Award prodigious and rare talent.