The Plaster-Filled Eggshell Gambit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Es Probable, De Hecho, Que La Invencible Tristeza En La Que Se

Surrealismo y saberes mágicos en la obra de Remedios Varo María José González Madrid Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – CompartirIgual 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – CompartirIgual 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0. Spain License. 2 María José González Madrid SURREALISMO Y SABERES MÁGICOS EN LA OBRA DE REMEDIOS VARO Tesis doctoral Universitat de Barcelona Departament d’Història de l’Art Programa de doctorado Història de l’Art (Història i Teoria de les Arts) Septiembre 2013 Codirección: Dr. Martí Peran Rafart y Dra. Rosa Rius Gatell Tutoría: Dr. José Enrique Monterde Lozoya 3 4 A María, mi madre A Teodoro, mi padre 5 6 Solo se goza consciente y puramente de aquello que se ha obtenido por los caminos transversales de la magia. Giorgio Agamben, «Magia y felicidad» Solo la contemplación, mirar una imagen y participar de su hechizo, de lo revelado por su magia invisible, me ha sido suficiente. María Zambrano, Algunos lugares de la pintura 7 8 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 13 A. LUGARES DEL SURREALISMO Y «LO MÁGICO» 27 PRELUDIO. Arte moderno, ocultismo, espiritismo 27 I. PARÍS. La «ocultación del surrealismo»: surrealismo, magia 37 y ocultismo El surrealismo y la fascinación por lo oculto: una relación polémica 37 Remedios Varo entre los surrealistas 50 «El giro ocultista sobre todo»: Prácticas surrealistas, magia, 59 videncia y ocultismo 1. «El mundo del sueño y el mundo real no hacen más que 60 uno» 2. -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

Chess Play Icons and the Staunton Chess Set Design

EARLY NINETEETH CENTURY CHESS PLAY ICON SETS, MODERN CHESS PLAY ICON SETS, AND THE STAUNTON CHESS SET OF 1849 “The Staunton pattern…[was] the basis of all modern figurines in diagrams...”. Ken Whyld, Chess Play Diagrams. With all due respect, Ken Whyld was wrong. Early nineteenth century chess play iconography rather than the Staunton chess set style of 1849 was the basis of our modern chess play diagrams. Chess play set icons identical to those we use today appeared in the works of English chess author William Lewis as of 1818. Moreover, specific elements of certain chess play icon sets used in the early nineteenth century publications of two English authors, Charles Stopford Kenny and William Lewis, predate the Staunton chess set while in toto they match the Staunton chess set’s design in every particular. This begs the question as to whether the famous Staunton Chess Set design was in fact an employment of shapes already familiar to chess students for over three decades. As of the early 1800s, books on chess play were numerous. These books often provided chess play diagrams along with the text. The symbols, or icons, used to represent the various game pieces were not, however, standardized: various authors and publishing houses used their own icon sets and symbols. Iconographic choice remained in flux over the next half century, both on the Continent and in England. However, English conventions (particularly as represented in the numerous works of Kenny and Lewis) came to dominate English, French and to a lesser degree American chess publications by circa 1830. -

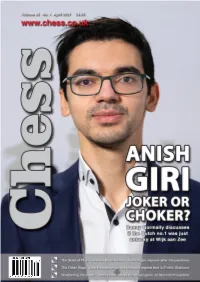

The Queen's Gambit

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

The English School of Chess: a Nation on Display, 1834-1904

Durham E-Theses The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM How to cite: HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM (2018) The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12703/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Edward Harrison This thesis is submitted for the degree of MA by Research in the department of History at Durham University March 2018 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the author's prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. -

Rules of Chess

Rules of chess From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The rules of chess (also known as the laws of chess) are rules governing the play of the game of chess. While the exact origins of chess are unclear, modern rules first took form during the Middle Ages. The rules continued to be slightly modified until the early 19th century, when they reached essentially their current form. The rules also varied somewhat from place to place. Today Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE), also known as the World Chess Organization, sets the standard rules, with slight modifications made by some national organizations for their own purposes. There are variations of the rules for fast chess, correspondence chess, online chess, and chess variants. Chess is a game played by two people on a chessboard, with 32 pieces (16 for each player) of six types. Each type of piece moves in a distinct way. The goal of the game is to checkmate, i.e. to threaten the opponent's king with inevitable capture. Games do not necessarily end with checkmate – players often resign if they believe they will lose. In addition, there are several ways that a game can end in a draw. Besides the basic movement of the pieces, rules also govern the equipment used, the time control, the conduct and ethics of players, accommodations for handicapped players, the recording of moves using chess notation, as well as procedures for irregularities that occur during a game. Contents 1 Initial setup 1.1 Identifying squares 2 Play of the game 2.1 Movement 2.1.1 Basic moves 2.1.2 Castling 2.1.3 En passant 2.1.4 Pawn promotion Game in a public park in Kiev, using a 2.2 Check chess clock 3 End of the game 3.1 Checkmate 3.2 Resigning 3.3 Draws 3.4 Time control 4 Competition rules 4.1 Act of moving the pieces 4.2 Touch-move rule 4.3 Timing 4.4 Recording moves 4.5 Adjournment 5 Irregularities 5.1 Illegal move 5.2 Illegal position 6 Conduct Staunton style chess pieces. -

Download the Latest Catalogue

TABLE OF CONTENTS To view a particular category within the catalogue please click on the headings below 1. Antiquarian 2. Reference; Encyclopaedias, & History 3. Tournaments 4. Game collections of specific players 5. Game Collections – General 6. Endings 7. Problems, Studies & “Puzzles” 8. Instructional 9. Magazines & Yearbooks 10. Chess-based literature 11. Children & Junior Beginners 12. Openings Keverel Chess Books July – January. Terms & Abbreviations The condition of a book is estimated on the following scale. Each letter can be finessed by a + or - giving 12 possible levels. The judgement will be subjective, of course, but based on decades of experience. F = Fine or nearly new // VG = very good // G = showing acceptable signs of wear. P = Poor, structural damage (loose covers, torn pages, heavy marginalia etc.) but still providing much of interest. AN = Algebraic Notation in which, from White’s point of view, columns are called a – h and ranks are numbered 1-8 (as opposed to the old descriptive system). Figurine, in which piece names are replaced by pictograms, is now almost universal in modern books as it overcomes the language problem. In this case AN may be assumed. pp = number of pages in the book.// ed = edition // insc = inscription – e.g. a previous owner’s name on the front endpaper. o/w = otherwise. dw = Dust wrapper It may be assumed that any book published in Russia will be in the Russian language, (Cyrillic) or an Argentinian book will be in Spanish etc. Anything contrary to that will be mentioned. PB = paperback. SB = softback i.e. a flexible cover that cannot be torn easily. -

Chess Sets from 1700 to the Introduction of the Staunton Design (1849)

Page 1 of 7 The Conventional Chess Sets from 1700 to the introduction of the Staunton Design (1849) Chesmayne Chess History Time Lines: 1500's . 1600's . 1700's . 1800's . 1900's Today, the Staunton design, named after a Chess Master in England, but actually developed by and produced by John Jaques of London in 1849, is now the standard design for chess pieces. Prior to that, a number of Conventional styles of turned chess sets preceded the introduction of the Staunton Design in 1849. These pieces were designed for play using simplified or abstract shapes and made of more inexpensive materials than more ornate displays sets. Some of these various styles were named after either the Coffee House/ Chess Clubs in London and Paris, and other European cities where they were used; or the skilled turners who created them. Along with these Conventional Playing Sets, there were also a variety of Representational Sets - the latter tended to be more for display than play. The original chess sets from the East were highly abstracted pieces. Early Western sets were carved figures such as the Lewis Chess men or those of Charlemagne's time. In the Middle Ages, Chess was a game mainly for the Nobility and Clergy. They could afford expensive ornate sets. During the Renaissance, it was still mainly a game for the households of kings such as Philip II of Spain or Henry the 8th; and the Queens, such as Catherine De Medici, or Elizabeth I. A revolution in Chess play in the West was the development of the powerful Chess Queen. -

Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos

Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos Staunton Chess Set Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos [email protected] Culture is the social use of human intelligence Gabriel García Márquez Contents: Introduction. 1. ORIGIN OF STAUNTON CHESS SET. 1.1. Novelty of the Registered Design. 1.2. Authorship and Place of Origin. 1.3. Importance of the Name. 1.4. Signature Guarantee. 2. OFFICIAL PIECES. 3. INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE. 3.1. Concept. 3.2. Reality and Formality. 3.3. Potential Advantages. 4. CHARACTERISTICS OF STAUNTON CHESS SET 4.1. Form and Function. 4.2. Special Features. 5. CURRENT SITUATION. Appendix: Brief list of major museums, private collections, and shops in Internet Classic Staunton Chess Set INTRODUCTION. As surprising as this may seem, not all the chess sets have been designed to play, hence, we find: 1 Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos - Functional pieces, designed to play, and - Ornamental pieces, designed to decorate (1) This article focuses on the best known functional pieces, called Staunton, which are widely accepted by casual and professionals players around the world. The Staunton chessmen were created in London in 1849, during the Victorian Era, over 160 years ago. They are masterpieces of functionality and elegance, so they have become the unique and unmistakable classic chess game pieces. Many players cannot imagine the game with other pieces. In 1924, these pieces were selected as the official set by the World Chess Federation; presently, for about 600 million players in over 120 countries, Stauton pieces are the choice of set. -

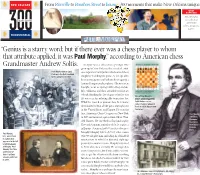

Genius Is a Starry Word; but If There Ever Was a Chess

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Paul Morphy 1718 ~ 2018 won the first American Chess Congress 300 in 1857. TRICENTENNIAL “ Genius is a starry word; but if there ever was a chess player to whom that attribute applied, it was Paul Morphy,” according to American chess Grandmaster Andrew Soltis. Morphy was a child chess prodigy who grew up in New Orleans, the son of a Louisi- Paul Morphy took on Louis ana Supreme Court justice who learned chess Paulsen in the first American Chess Congress in 1857. simply by watching the game. At the age of 12, he won two games and had one draw against a famous Hungarian chess player. The next year, Morphy went to Spring Hill College in Mo- bile, Alabama, and then attended Loyola Law School, finishing his law degree when he was One of Paul Morphy’s 20, one year shy of being able to practice law. moves against opponent While he waited to practice law, he became Adolf Anderssen in a series of games played in determined to beat all the great chess players Paris in 1858. Morphy won in the United States and Europe. He won the the series. first American Chess Congress in New York ‘Paul Morphy in 1857 and received a prize from Oliver Wen- - The Chess Champion’ dell Homes. He traveled to England to play illustration Howard Staunton, considered the best player from Ballou’s in Europe. Staunton, however, refused to meet Pictorial, 1859. Morphy. Morphy defeated every other comer Paul Morphy, left, and a friend who would play him, including in a blindfold in a photo that tournament in which he defeated eight op- appeared in the full- length biography ponents in another room. -

Still SELF-UPDATING

GE THE ORIGINS OF SYNTHETIC TIMBRE SERIALISM AND THE PARISIAN CONFLUENCE, 1949–52 by John-Philipp Gather October 2003 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music COPYRIGHT NOTE The first fifty copies were published by the author. Berlin: John-Philipp Gather, 2003. Printed by Blasko Copy, Hilden, Germany. On-demand copies are available from UMI Dissertation Services, U.S.A. Copyright by John-Philipp Gather 2003 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many persons have contributed to the present work. I would like to name first and foremost my major advisor Christopher Howard Gibbs for his unfailing support and trust throughout the five-year writing period, guiding and accompanying me on my pathways from the initial project to the present study. At the State University of New York at Buffalo, my gratitude goes to Michael Burke, Carole June Bradley, Jim Coover, John Clough, David Randall Fuller, Martha Hyde, Cort Lippe, and Jeffrey Stadelman. Among former graduate music student colleagues, I would like to express my deep appreciation for the help from Laurie Ousley, Barry Moon, Erik Oña, Michael Rozendal, and Matthew Sheehy. A special thanks to Eliav Brand for the many discussion and the new ideas we shared. At the Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, I am grateful to Jacquelyn Thomas, Peter Schulz, and Rohan Smith, who helped this project through a critical juncture. I also extend my warm thanks to Karlheinz Stockhausen, who composed the music at the center of my musicological research. -

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics This volume examines the relationship between occultism and Surrealism, specif- ically exploring the reception and appropriation of occult thought, motifs, tropes and techniques by surrealist artists and writers in Europe and the Americas from the 1920s through the 1960s. Its central focus is the specific use of occultism as a site of political and social resistance, ideological contestation, subversion and revolution. Additional focus is placed on the ways occultism was implicated in surrealist dis- courses on identity, gender, sexuality, utopianism and radicalism. Dr. Tessel M. Bauduin is a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Lecturer at the Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Dr. Victoria Ferentinou is an Assistant Professor at the University of Ioannina. Dr. Daniel Zamani is an Assistant Curator at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Cover image: Leonora Carrington, Are you really Syrious?, 1953. Oil on three-ply. Collection of Miguel S. Escobedo. © 2017 Estate of Leonora Carrington, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2017. This page intentionally left blank Surrealism, Occultism and Politics In Search of the Marvellous Edited by Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani First published 2018 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Taylor & Francis The right of Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.