Love Poems for Photographs and Other Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Book Progeo 2Ed 20

Abstract Book BUILDING CONNECTIONS FOR GLOBAL GEOCONSERVATION Editors: G. Lozano, J. Luengo, A. Cabrera Internationaland J. Vegas 10th International ProGEO online Symposium ABSTRACT BOOK BUILDING CONNECTIONS FOR GLOBAL GEOCONSERVATION Editors Gonzalo Lozano, Javier Luengo, Ana Cabrera and Juana Vegas Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 2021 Building connections for global geoconservation. X International ProGEO Symposium Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 2021 Lengua/s: Inglés NIPO: 836-21-003-8 ISBN: 978-84-9138-112-9 Gratuita / Unitaria / En línea / pdf © INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Ríos Rosas, 23. 28003 MADRID (SPAIN) ISBN: 978-84-9138-112-9 10th International ProGEO Online Symposium. June, 2021. Abstracts Book. Editors: Gonzalo Lozano, Javier Luengo, Ana Cabrera and Juana Vegas Symposium Logo design: María José Torres Cover Photo: Granitic Tor. Geosite: Ortigosa del Monte’s nubbin (Segovia, Spain). Author: Gonzalo Lozano. Cover Design: Javier Luengo and Gonzalo Lozano Layout and typesetting: Ana Cabrera 10th International ProGEO Online Symposium 2021 Organizing Committee, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Juana Vegas Andrés Díez-Herrero Enrique Díaz-Martínez Gonzalo Lozano Ana Cabrera Javier Luengo Luis Carcavilla Ángel Salazar Rincón Scientific Committee: Daniel Ballesteros Inés Galindo Silvia Menéndez Eduardo Barrón Ewa Glowniak Fernando Miranda José Brilha Marcela Gómez Manu Monge Ganuzas Margaret Brocx Maria Helena Henriques Kevin Page Viola Bruschi Asier Hilario Paulo Pereira Carles Canet Gergely Horváth Isabel Rábano Thais Canesin Tapio Kananoja Joao Rocha Tom Casadevall Jerónimo López-Martínez Ana Rodrigo Graciela Delvene Ljerka Marjanac Jonas Satkünas Lars Erikstad Álvaro Márquez Martina Stupar Esperanza Fernández Esther Martín-González Marina Vdovets PRESENTATION The first international meeting on geoconservation was held in The Netherlands in 1988, with the presence of seven European countries. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Vicente Cervantes (1758-1829) Relaciones Científicas Y Culturales Entre España Y América Durante La Ilustración

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia: Portal Publicaciones En el 250 aniversario del nacimiento de Vicente Cervantes (1758-1829) Relaciones científicas y culturales entre España y América durante la Ilustración Sesión Científica Coordinada por el Excmo. Sr. D. Bartolomé Ribas Ozonas Madrid, 11 de septiembre de 2008 REAL ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE FARMACIA ISBN: 978-84-936890-9-4 Depósito legal: M. 28.310-2009 Imprime: Realigraf, S.A. Pedro Tezano, 26 28039 Madrid ÍNDICE Prólogo. María Teresa Miras Portugal, Antonio Doadrio Villarejo, Antonio Gon- zález Bueno ................................................................................................................. 7 El 250 aniversario del nacimiento de Vicente Cervantes Mendo (Ledrada, Salamanca, 17-II-1758 / México D.F., 26-VII-1829). Javier Puerto ................... 9 Vicente Cervantes Mendo, científico hispano-mexicano insigne: datos para una biografía. José Pastor Villegas ......................................................................... 19 Una visión de Vicente Cervantes Mendo en la enseñanza de la Botánica y de la Farmacia. María del Carmen Francés Causapé ................................................ 53 La Historia Natural en el México de las Ciencias y de las Luces (1790-1794). J. Luis Maldonado Polo ............................................................................................ 69 Vicente Cervantes, el Jardín Botánico de Madrid, Gómez Ortega y la Expe- dición a Nueva -

Heart Land Damian Elwes Damian Elwes Heart Land

Cover: Blue Wind (detail), 2011 mixed media on canvas 107 x 168 cm First published in 2011 by Agent Morton Ltd www.agentmorton.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and the publishers. All images in this catalogue are protected by copyright and should not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Details of the copyright holder to be obtained from Agent Morton Ltd. Tel: +44 207 409 1395 Copyright 2011 Agent Morton Ltd 32 Dover Street, W1S 4NE Designed and produced in the UK by Footprint. www.fpiltd.com www.agentmorton.com HEART LAND DAMIAN ELWES DAMIAN ELWES HEART LAND 20 June - 29 July 2011 Tel: +44 207 409 1395 32 Dover Street, W1S 4NE www.agentmorton.com HEART LAND Unlike Gauguin, when Damian Elwes left ‘civilization’ to find his personal Garden of Eden and live in tropical, colour-saturated, visceral nature, he took his wife with him. At their home on a little coffee farm on the edge of the Colombian rainforest, Elwes painted dioramas of the forest in an attempt to express our deep connection to the natural world. He also made endless nude drawings of his wife. It was a response to seeing Lewanne so profoundly immersed in her environment, he says, a desire to record the naturalness and sense of freedom she exhibited by walking around naked. It began to occur to him that women are so fundamentally connected to nature, through their physiological and mythical relationship to the moon and in motherhood, that they more perfectly embody this connectivity than a tree or a mountain. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Newsletter, Number 55, Fall 2020

Number 55 – Fall 2020 NEWSLETTERAlumni PatriciaEichtnbaumKaretzky andZhangEr Neoclasicos rnE'-RTISTREINVENTiD,1~1-1= THEME""'lLC.IIEllMNICOLUCTION MoMA Ano M. Franco .. ..H .. •... 1 .1 e-i =~-:.~ CALLi RESPONSE Nyu THE INSTITUTE Published by the Alumni Association of II IOF FINE ARTS 1 Contents Letter from the Director In Memoriam ................. .10 The Year in Pictures: New Challenges, Renewed Commitments, Alumni at the Institute ..........16 and the Spirit of Community ........ .3 Iris Love, Trailblazing Archaeologist 10 Faculty Updates ...............17 Conversations with Alumni ....... .4 Leatrice Mendelsohn, Alumni Updates ...............22 The Best Way to Get Things Done: Expert on Italian Renaissance An Interview with Suzanne Deal Booth 4 Art Theory 11 Doctors of Philosophy Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 The IFA as a Launching Pad for Seventy Nadia Tscherny, Years of Art-Historical Discovery: Expert in British Art 11 Master of Arts and An Interview with Jack Wasserman 6 Master of Science Dual-Degrees Dora Wiebenson, Conferred in 2019-2020 .........34 Zainab Bahrani Elected to the American Innovative, Infuential, and Academy of Arts and Sciences .... .8 Prolifc Architectural Historian 14 Masters Degrees Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 Carolyn C Wilson Newmark, Noted Scholar of Venetian Art 15 Donors to the Institute, 2019-2020 .36 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Offcers: Alumni Board Members: Walter S. Cook Lecture Susan Galassi, Co-Chair President Martha Dunkelman [email protected] and William Ambler [email protected] Katherine A. Schwab, Co-Chair [email protected] Matthew Israel [email protected] [email protected] Yvonne Elet Vice President Gabriella Perez Derek Moore Kathryn Calley Galitz [email protected] Debra Pincus [email protected] Debra Pincus Gertje Utley Treasurer [email protected] Newsletter Lisa Schermerhorn Rebecca Rushfeld Reva Wolf, Editor Lisa.Schermerhorn@ [email protected] [email protected] kressfoundation.org Katherine A. -

Isotope and Nuclear Chemistry Division Annual Report, FY 1990, October 1, 1989

LA12143-PR Progren Report Isotope dnd Nuclecqr Chemistry Division Ann vial Report FY 1990^ .. •• %-•-' V \ ? L«>Alaa^Natkif^'ljri>oratoryk operated by the UnhrcnUy of Colitbr^ Geologists inspect the Devil's Thumb Sinkhole, which is located in travertine at the base of the Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces, before injecting multiple tracers to determine flow paths, transit times, and chemical Water from Boiling River (Mammoth Hot reaction processes in a natural aquifer. Hot Springs) was sampled at many intervals during a water from pools on top of this terrace flows multicomponent tracer experiment. Analysis of over the orange travertine and down into the data from this major outflow of the Mammoth sinkhole. Inactive travertine is grey; the oldest system (-40°C and 27 f&ls flow rate) provides deposits support several types of trees. information about the flow path, transit titles, and chemical reaction processes of a natural aquifer. This information is used to test hypotheses and field approaches for characterizing geothermal, petroleum, and environmental reservoirs. A team of geologists collected more than 250 samples over an 18-hr period at Boiling River —one of many remote field sample processing sites—during the multicomponent tracer experiment. In this wilderness area, team members used the environmentally benign transport system (shown in red) to move equipment and samples. Closeup of the Devil's Thumb Sinkhole shows wet, actively depositing travertine in orange and old, degrading travertine in white. These moths caught in the hot springs were fossilized as hydrothermal solutions flowed across the ground surface at Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park. -

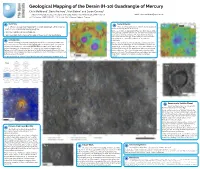

Geological Mapping of the Derain (H-10) Quadrangle of Mercury

Geological Mapping of the Derain (H-10) Quadrangle of Mercury Chris Malliband1, David Rothery1, Matt Balme1 and Susan Conway2 1 - School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK Email: [email protected] 2– LPG Nantes, UMR CNRS 6112, BP 92208, 44322 Nantes Cedex 3, France 1 Summary Fig. 2 Ancient Basins 3 Fig. 3 We are geologically mapping the Derain quadrangle of Mercury as There are two possible basins identified and catalogued part of a co-ordinated mapping program. as B30 and B36 by Fasset et. al. (2012). B36 is easily visible in topography (Fig 2) and MDIS mosaic with a We have completed crater mapping. clear, partially complete western rim. The eastern boundary has We have identified a range of notable of features in the quadrangle. been obscured by later impacts. We have identified impacts here of at least Calorian age. Unlike other pre-Calorian basins (eg Tolstoj) there is no visible evidence of later volcanic 2 Introduction resurfacing. We are currently geologically mapping the Derain (H-10) quadrangle of Mercury. B30 is in the north west of the quadrangle, and extends north The location of Derain in relation to other quadrangles is shown in Figure 1. Derain was into the Hokusai quadrangle. It is more evident in elevation (as not imaged by Mariner 10, and so this MESSENGER based work is the first detailed shown in fig. 3) than the MDIS mosaic. The reported diameter of geological mapping of the quadrangle. This is part of the European mapping effort 1390km (Fasset et. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Bradley J

CURRICULUM VITAE Bradley J. Thomson Assistant Professor Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences Phone: 865.974.2699 University of Tennessee Fax: 865.974.2368 1621 Cumberland Ave., Room 602 Email: [email protected] Knoxville, TN 37996-1410 Website: https://lunatic.utk.edu EDUCATION Ph.D. Geological Sciences, Brown University, 2006 Dissertation title: Recognizing impact glass on Mars using surface texture, mechanical properties, and mid-infrared spectroscopic properties Advisor: Peter H. SchultZ M.Sc. Geological Sciences, Brown University, 2001 Thesis title: Utopia Basin, Mars: Origin and evolution of basin internal structure Advisor: James W. Head III B.S. Harvey Mudd College, 1999, Geology major at Pomona College Thesis title: Thickness of basalts in Mare Imbrium Advisor: Eric B. Grosfils PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Assistant Professor, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences (EPS), University of Tennessee, Knoxville TN, 2020–present Research Associate Professor, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences (EPS), University of Tennessee, Knoxville TN, 2016–2020 Senior Research Scientist, Boston University Center for Remote Sensing, 2011–2016 Co-Investigator, Mini-RF radar on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, 2009–present Co-Investigator, Mini-SAR radar on Chandrayaan-1, 2008–2009 Senior Staff Scientist, JHU Applied Physics Lab, 2008–2011 NASA Postdoctoral Program Fellow, Jet Propulsion Lab, 2006–2008 Science Theme Lead for mass wasting processes HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, 2007–2010 Postdoctoral Fellow, Lunar and Planetary -

Get Smart with Art Is Made Possible with Support from the William K

From the Headlines About the Artist From the Artist Based on the critics’ comments, what aspects of Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) is Germany in 1830, Albert Bierstadt Bierstadt’s paintings defined his popularity? best known for capturing majestic moved to Massachusetts when he western landscapes with his was a year old. He demonstrated an paintings of awe-inspiring mountain early interest in art and at the age The striking merit of Bierstadt in his treatment of ranges, vast canyons, and tumbling of twenty-one had his first exhibit Yosemite, as of other western landscapes, lies in his waterfalls. The sheer physical at the New England Art Union in power of grasping distances, handling wide spaces, beauty of the newly explored West Boston. After spending several years truthfully massing huge objects, and realizing splendid is evident in his paintings. Born in studying in Germany at the German atmospheric effects. The success with which he does Art Academy in Düsseldorf, Bierstadt this, and so reproduces the noblest aspects of grand returned to the United States. ALBERT BIERSTADT scenery, filling the mind of the spectator with the very (1830–1902) sentiment of the original, is the proof of his genius. A great adventurer with a pioneering California Spring, 1875 Oil on canvas, 54¼ x 84¼ in. There are others who are more literal, who realize details spirit, Bierstadt joined Frederick W. Lander’s Military Expeditionary Presented to the City and County of more carefully, who paint figures and animals better, San Francisco by Gordon Blanding force, traveling west on the overland who finish more smoothly; but none except Church, and 1941.6 he in a different manner, is so happy as Bierstadt in the wagon route from Saint Joseph, Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery, San Francisco. -

2004 Issue11 2004.Pdf

������������������������������������������ �������� �������� �������� ��������������� ������������������� ������� ����������������� ����������������� �������������������� ������������������� ������������������������� ���������������� ���������������������� ��������������������� ���������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������� 2 ISSUE ELEVEN: DECEMBER 03 - JANUARY 13, 2005 Articles 06 Iceland’s Homeless Problem Can it be solved 08 Why the Bush Regime Will Bomb Iraq But Never Ban Abortion A letter from America 14 “The Minister of Education is a Joke” A teacher speaks her mind The Reykjavík Grapevine crew 22 Will Mouth Tobacco Turn You into a Sexual Tyrannosaurus? The Reykjavík Grapevine Hafnarstræti 15, 2nd floor www.grapevine.is Feature : God Rules! [email protected] Published by: Bazar ehf. 17 Can Jesus, Allah and Science all coexist? Editors: 561-2323 / 845-2152 / 18 God: The Interviews [email protected] Six spiritual people from the Bishop to the pagan Chieftain explain their Advertising: 562-1213 / 869-7796 / [email protected] theories on the Divine. Distribution: 562-1213 / 898-9249 / [email protected] Production: 561-2329 / 849-5611 /[email protected] usic & ightlife Listings: 562-1213 / 869-7796 / [email protected] M N Subscription: 561-2329 / 849-5611 /[email protected] 23 Like a Kraftwerk Christmas Album Had There Publisher: Hilmar Steinn Grétarsson / [email protected] Ever Been One Editor: Valur Gunnarsson / [email protected] 32 Five Main -

Extraordinary Encounters: an Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings

EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS An Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings Jerome Clark B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by Jerome Clark All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Jerome. Extraordinary encounters : an encyclopedia of extraterrestrials and otherworldly beings / Jerome Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-249-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 1-57607-379-3 (e-book) 1. Human-alien encounters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF2050.C57 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-011350 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. To Dakota Dave Hull and John Sherman, for the many years of friendship, laughs, and—always—good music Contents Introduction, xi EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EXTRATERRESTRIALS AND OTHERWORLDLY BEINGS A, 1 Angel of the Dark, 22 Abductions by UFOs, 1 Angelucci, Orfeo (1912–1993), 22 Abraham, 7 Anoah, 23 Abram, 7 Anthon, 24 Adama, 7 Antron, 24 Adamski, George (1891–1965), 8 Anunnaki, 24 Aenstrians, 10 Apol, Mr., 25