Built Environment Topic Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin 41 4 Winter

Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 41 Number 4 Winter 2011 SHS Bulletin Vol. 41 No. 4 Winter 2011 Bulletin of the Saddleworth Historical Society Volume 41 Number 4 Winter 2011 Chairman’s Report 93 Mike Buckley Celebrating Royal Occasions 96 Neil Barrow Saddleworth’s Beer Houses 98 Peter Fox Interesting Newspaper Articles 107 Alison Wild Letters 110 Index to Volume 4 112 Alan Schofield Cover Illustration: Sketch by Ammon Wrigley of the Woodman Inn, Delph (Saddleworth Museum Collection M/AW/6/30.) ©2011 Saddleworth Historical Society and individual contributors i ii SHS Bulletin Vol. 41 No. 4 Winter 2011 CHAIRMAN'S REPORT TO THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2011 Mike Buckley In the last twelve months the big event for us has been the launch of the second volume of Mapping Saddleworth. This took place on the 25th September, three days after our Annual General Meeting. The launch was combined with a day school on “Mapping the Past” which was held under the auspices of the South Pennine History Forum, a group of local history societies from across the South Pennines. Much of our efforts since the launch have been directed towards promoting sales of the book and during the year we have held several exhibitions and book-signing events. The production of the book has been a monumental task for the Society and I would like to pay tribute to all the hard work that went into it by the publications committee. But all the effort has been worth it; the book is a wonderful production which enhances our reputation as a local historical society. -

Dig Greater Manchester Is Go! Newsletter

Greater Manchester Archaeology Federation Newsletter Volume 1 Issue 8 March 2012 Dig Greater Manchester 1-2 GM Archaeology Day 2011 7-9 Dig Greater Society Reports 4-6, 11,17 Discoveries 10-13 Manchester GM Past Revealed 14-15 CfAA Report 16 is go! GMAU Report 21-22 ObituaryObituary————BenBen Edwards 181818-18 ---20202020 New Society! The Federation welcomes an- other new member, the Mid- dleton Archaeological Society. There will be a piece about the Society in a future issue of the newsletter. Introduction Dig Greater Manchester (DGM) is an archaeologically based project funded by the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (AGMA) and the borough of Blackburn with Darwen. The project will build on the suc- cess of community heritage engagement projects such as ‘Dig Manchester’ and other successful community projects established by the Centre for Applied Archaeology (CfAA), the now closed University of Manchester Archaeology Unit (UMAU) in conjunction with the Greater Manchester Archaeology Unit (GMAU) and local au- thorities and politicians from the Greater Manchester area. The five year project will be led by staff from the CfAA and managed by members of all project partners. Although professionally led its overall aim is to involve the highest number of people from the local communities in the investigation of their Heritage. The project will have dedicated personnel including the lead archaeologist, dealing with the overall manage- ment and organisation of the project, and a dedicated educational/outreach archaeologist whose main task will be to organise the educational aspects. The Project The project will include an archaeological evaluation in every one of the participating boroughs each lasting for a two week period. -

Agecroft in Steam

( ?I ~- - - ~"~ _., -- ........... / -- . , ·--....., __ t) \ ,-- The 1960's saw a dramatic change m the use of The 'A' station system was abandoned early m steam locomotion in the North West of 1947 as construction of 'B' station cooling to Cl!Jton Junc1:c'n ) England. Within the short space of 8 years the towers severed the line. Between then and its QI✓ . familiar sight of a steam-hauled train closure the 'A' station received coal by road. {not all 1he rm,ways shown exi~ad al the some time vanished completely from British Rail. For a A Stallon .,:· :·, ,: ' _::' .·. ·-~ ·.. while steam continued to be used at some ·'..,·.'. _. 1, · ,_ c · ·n... c····. ~:·y···,--·· Reception Sidings industrial sites in Lancashire but now only II AG hopper Agecroft Power Station, near Manchester, .if •i•>,c': fp , ' . ,. Ill ·• continues the tradition. Three power stations (A, B and C ) have been A completely ne w coal handling system using developed on the Agecroft site smce 1925 and steam locomotives, was built on a separate each has used a rrnl system in its coal site· to se rve···•· both 'B ' and 'C' stations. A senes of handling. lines, approximately I mile lung, was coalslockmg construc ted running from the original gmundwilh ,:···. ~ ~ -c·,.' .-:B.ft. .,. ....:;: y ·:·:· conveyor to Agecroft Junc tion. The line passed crone lrack (standard gmrgel -.. ~~:: .. ·~&--... 2 loco sheds and fanned into wagon sidings ,,,. .-n:v ...' ... which converged lo pass through the tippler. .. .. A new conveyor was built to take the coal over . .. ... the British Rail line and the canal to the power The original 'A' statio,n used a 2' 6" gauge station. -

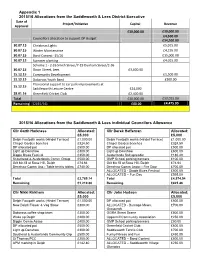

Appendix 1 2015/16 Allocations from the Saddleworth & Lees District Executive

Appendix 1 2015/16 Allocations from the Saddleworth & Lees District Executive Date of Project/Initiative Capital Revenue Approval £30,000.00 £30,000.00 £4,500.00 Councillors allocation to support DP Budget £34,500.00 30.07.15 Christmas Lights £5,015.00 30.07.15 Winter Maintenance £4,195.00 30.07.15 Band Contest -15/16 £15,000.00 30.07.15 Summer planting £4,015.00 Scheme 1 - 2-26 Smith Street/7-19 Dunham Street/2-36 30.07.15 Dixon Street, Lees £3,600.00 15.12.15 Community Development £1,500.00 15.12.15 Dobcross Youth Band £300.00 Provisional support to car park improvements at 15.12.15 Saddleworth Leisure Centre £24,000 28.01.16 Greenfield Cricket Club £2,400.00 Total £30,000.00 £30,025.00 Remaining (2015/16) £00.00 £4,475.00 2015/16 Allocations from the Saddleworth & Lees individual Councilors Allowance Cllr Garth Harkness Allocated: Cllr Derek Heffernan Allocated: £5,000 £5,000 Delph Footpath works (Hindel Terrace) £1,000.00 Delph Footpath works (Hindel Terrace) £1,000.00 Chapel Garden benches £324.50 Chapel Garden benches £324.50 DP allocated pot £500.00 DP allocated pot £500.00 Light up Denshaw £300.00 Light up Denshaw £600.00 Diggle Blues Festival £350.00 Austerlands Salt spreader £180.40 Scouthead & Austerlands Comm Group £500.00 GMP School parking banners £100.00 Grit bin fill at Rose Hill, Delph £74.64 Grit bin fill at Rose Hill, Delph £74.64 Denshaw Comm Ass - Table tennis tables £740.00 Denshaw Comm Assoc - Fire Door £700.00 ALLOCATED - Diggle Blues Festival £500.00 ALLOCATED – Fun Day £595.00 Total £3,789.14 Total £4,574.54 -

Saddleworth. 857

SADDLEWORTH. 857 Woollen Carders. :BjQ.'om Rt. & Jas. Summer hill Schofield Wm. Bl~akhey Nook Howard Henry, Castle ClouO'h *Cliflon Jnthn. Carcote, Delph Shaw & Bradbury, Upper Mill Mill; ho. Lane, Staley o Cooper .Tames, W~ hill Shaw Dan (shawl), Hill end Howard Wm. & Alfred, Lower Cooper Robert, Albwn Cottage Shaw James, Oxhey Castle Clough Mill; ho. Lane, Firth J ames, Oxhey Shaw J ames, Knowl Staley Gartside John & Joseph, Delph Shaw John (wool carder), Dale Pontefract Jerry & James,Tame Hastings Brothers, Delph Shaw ~alph, Shepherd's _green Water Dobcross HawkyardRalph(woollenshawl) Shaw 'Ihomas, Upper :Mill ' Furlane Shaw William, Micklehurst Woollen Cloth Manufacturers. Hirst John Pob green Smith Joseph Tamewater Dob~ l\Iarked thus* are also Merchants. •Hirst Joh~ & Sons Dobcross cross ' ' Alexander Robert, RoyalGeorge Holden William, Causey' sett Sykes Benjamin & Son, Diglee Mills; ho. Friezland House Hyde George & J oseph ( & wool Whitehead & Shaw, Long road Bottomley James and Moses, merchants),Castle Mill,Staley Mill & New Year's bridg~, Weakey . Kenworthy Benj. Castle Shaw Denshaw Bottomley James, Holly grove Kenworthy Thos. Castle Shaw Whitehead Benj. Upper l\Iill •Bottomley James, Greenfield Kershaw Hugh, Micklehurst Whitehead Jas. Church banks Bradbury & Whitehad,Andrews •Lawton Geo. Vale Mill, Mick- Whitehead James, Denshaw Mill lehurst,nr.Ashton-under-Lpne Whitehead John, Tunstead Bradbury James, Thurstans I,awton Joe, Mossley Whitehead John, Sandbed *Bradbury John, Ryefields Lawton John, Green ash Whitehead Ralph, Saddleworth *Bradbury John, Brown hill Longbottom Eli, Oxhey, Delph fold Bradbury Ralph Thomas, Hey Longbottom John, Moore croft Whitehead Ralph Radcliffe & bottoms; ho. Kinders * Mallalieu J ames, Bank top Brothers ( & cotton & linen Bradbury Rhoda, Shaw hall MaUalieu John, Halls cloth), Royal George Mills Bradbury Jonathan, Greaves •Mallaliea Joseph, Delph Slack Whitehead Robert, Shaw halt Bradbury Thomas, Kinders, nr. -

Saddleworth Historicalsociety Bulletin

Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 49 Number 4 2019 Bulletin of the Saddleworth Historical Society Volume 49 Number 4 2019 Acting Chairman’s Address to the AGM 103 David Harrison The Development and Decline of Railways in the Saddleworth Area - Part 4 of 4 106 David Wharton-Street and Alan Young Saddleworth Freemasons - Lodge of Candour 1812 - 1851 124 Howard Lambert The Dobcross Loomworks Shunter or ‘The Dobcross Donkey’ 128 Peter Fox Arthur Hirst’s Diary - Errata 130 Index 132 Alan Schofield Cover Illustration: Emblem of the Freemason's Candour Lodge, Uppermill ©2019 Saddleworth Historical Society and individual contributors and creators of images. ii SHSB, VOL. 49, NO. 4, 2019 ACTING CHAIRMAN’S ADDRESS TO THE AGM 2019 David J. W. Harrison We are very sad to have to report that one of the new members of your committee, Peter Robinson, died last March. This was obviously a great loss to his family, and also to his friends, all to whom we extend our heart-felt condolences. Peter had only just commenced his service with the committee and was looking forward to help the Society grow. His loss is our sad loss. Your committee is still struggling to operate as well as we would wish due to a reduction in the number of trustees. There just aren’t enough to carry on the business of the Society properly. This year Charles Baumann has left the committee after many years of service when he undertook various tasks such as chairing lectures, organizing fund raising Flea Markets with me, publicising our events and other ventures as the need arose. -

Voice of Saddleworth News from Your Independent Councillors Denshaw, Delph, Dobcross, Diggle, Austerlands and Scouthead

Voice of Saddleworth News from your Independent Councillors Denshaw, Delph, Dobcross, Diggle, Austerlands and Scouthead SADDLEWORTH DESERVES BETTER! Vote For Change on May 22 Nikki Kirkham a Voice for Saddleworth Life-long Delph resident Nikki Kirkham, against the house-building agenda is standing as a Saddleworth that is threatening the landscape and Independent candidate in the local character of Saddleworth. She says: elections on May 22. Born in "We urgently need a tougher planning Denshaw, Nikki has lived in Delph regime and greater control at a local since she was three years old. level. We must protect our green belt and its natural beauty - not just for A working mum, Nikki is leader of the ourselves but also for our children. At Delph Methodist Cubs, a member of the same time we desperately need the Wake-Up Delph Committee (which affordable housing for first time buyers organises Party in The Park every and the elderly - something apparently year), and represents Delph and Den- forgotten by the Oldham planners. shaw on Saddleworth Parish Council. "All three political parties at Oldham She is sick of point-scoring party have consistently neglected politics and has chosen to be an Saddleworth. I will not be bound by independent so she can focus on the Oldham party politices. If you elect me, Nikki believes Saddleworth needs of Saddleworth residents. I’ll fight to get a better deal for deserves a better deal. If elected, Nikki promises to fight Saddleworth." IT'S A TWO HORSE RACE! Only 57 Votes Needed to Win In both the 2011 and 2012 borough elections only a handful of votes separated the Saddleworth Independents and the Liberal Democrat candidates. -

Bulletin Vol 48 No 4

Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 48 Number 4 2018 Bulletin of the Saddleworth Historical Society Volume 48 Number 4 2018 Secretary’s Address to the AGM 103 David Harrison Manor House, Churchfields, Dobcross, - A Reappraisal 105 Mike Buckley Saddleworth Notices and Reports from The Leeds Intelligencer: Part 5, 1979 - 1800 118 Howard Lambert Index 124 Alan Schofield Cover Illustration: The Manor House, Dobcross David JW Harrison ©2018 Saddleworth Historical Society and individual contributors and creators of images. ii SHSB, VOL. 48, NO. 4, 2018 SECRETARY’S ADDRESS TO THE AGM 2018 David J. W. Harrison We are most saddened to have to report that one of your committee, Tony Wheeldon, died sudden- ly last week (3 Oct.). This was obviously a great loss to his family, and also to his many friends, all to whom we extend our heart-felt condolences. Tony has been of great help to the Society during his all too short a tenure as committee member, taking on all sorts of tasks, particularly those of a physical nature now becoming beyond the reach of some of us. The Society is in a poorer state for his passing. Your committee is still struggling to operate as well as we would wish through lack of committee members. There just aren’t enough to carry on the business of the Society properly. Recent fall outs from the committee include our hard working publicity officer, Charles Baumann, who has resigned due to family and other commitments however he has intimated that he would be available to help out on occasion subject to his availability from his other extensive interests. -

Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Bolton Councillor Linda

NOTICE OF DECISIONS TAKEN BY THE GMCA ON 29 JUNE 2018 PRESENT: Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Bolton Councillor Linda Thomas Bury Councillor Rishi Shori Manchester Councillor Richard Leese Oldham Councillor Sean Fielding Rochdale Councillor Allen Brett Salford City Mayor Paul Dennett Stockport Councillor Alex Ganotis Tameside Councillor Brenda Warrington Trafford Councillor Andrew Western Wigan Councillor Keith Cunliffe OTHER MEMBERS IN ATTENDANCE: TfGMC Councillor Mark Aldred Salford Councillor Paula Boshell Stockport Councillor Wendy Wild Wigan Councillor Jenny Bullen OFFICERS IN ATTENDANCE: GMCA Chief Executive Eamonn Boylan GMCA –Deputy Chief Executive Andrew Lightfoot GMCA – Monitoring Officer Liz Treacy GMCA – Treasurer Richard Paver Office of the GM Mayor Kevin Lee Bolton Gerry Brough Bury Paul Patterson Oldham Carolyn Wilkins Manchester Geoff Little Rochdale Steve Rumbelow Salford Jim Taylor Stockport Caroline Simpson Tameside Steven Pleasant Trafford Gill Colbert Wigan Donna Hall Manchester Growth Company Mark Hughes TfGM Jon Lamonte GMP Ian Piling GMFRS Dawn Docx GMCA Julie Connor 1 GMCA Sylvia Welsh GMCA Lindsay Dunn GMCA Nicola Ward APOLOGIES: Bolton Tony Oakman Bury Pat Jones-Greenhalgh Manchester Joanne Roney Stockport Pam Smith Trafford Theresa Grant Wigan Cllr David Molyneux GMHSC Partnership Jon Rouse GMP Ian Hopkins Agenda Item No. 1. CHAIRS ANNOUNCEMENTS RESOLVED /- 1. That the thanks and appreciation, on behalf of the GMCA be recorded to the Interim Fire Officer, Dawn Docx and all staff at the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, particularly those working at the scene. The support of Fire and Rescue Services from Derbyshire, Lancashire, West Yorkshire and Gloucestershire and armed forces from the Royal Regiment of Scotland was recognised in helping continuously to control the fires on Saddleworth Moor, Winter Hill and in Rochdale. -

Issue 13 Issue 13 £1 £1

December December2019 & 2019 & December 2020 January 2020 Issue 13 Issue 13 £1 £1 ““CelebratingCelebrating God God’s’s presence presence in in all all people. people.”” www.cofeinsaddleworth.org.uk www.cofeinsaddleworth.org.uk - - - 2 - The Rector writes... Returning to Saddleworth after five months of being unwell, I look forward to Advent and the Christmas season. There is something powerful about discovering that in times of darkness and the icy winter of the soul the whisper of God’s breath is not absent. The presence of God is more a spark or the subtle flicker of a tiny flame than the glare of fairy lights and Christmas decorations. Through Advent we watch with those who live with darkness; with fear; with anxiety. We watch for the glimpses of God at work and we wait for dawn to break. And as we wait for the shadows to pass Index and the sun to rise we begin to see that the birth of Jesus is but one Page of many manifestations of God. In the gloom we see what God has always been revealing through beauty, colour, music, birdsong; that The Rector writes… 3 God delights in giving himself to us; pouring out his life for us; Portraying the Nativity 4 touching us with his grace. ‘Making a Difference’ 1 4 I have discovered fragility, vulnerability, betrayal and unfathomable #FollowTheStar 5 sadness, yet I have known also the beautiful, mysterious power of Who’s Who 6 love and prayer and friendship. Jesus himself knew all these things and at Christmas he comes again, searching for us and inviting us Christmas Quiz 7 to come to the manger. -

Cotton Mills for the Continent

cotton mills_klartext.qxd 30.05.2005 9:11 Uhr Seite 1 Cotton mills for the continent Sidney Stott und der englische Spinnereibau in Münsterland und Twente Sidney Stott en de Engelse spinnerijen in Munsterland en Twente 1 cotton mills_klartext.qxd 30.05.2005 9:11 Uhr Seite 2 Cotton mills for the continent Bildnachweis/Verantwoording Sidney Stott und der englische Spinnereibau in afbeldingen Münsterland und Twente – Sidney Stott en de Engelse spinnerijen in Munsterland en Twente Andreas Oehlke, Rheine: 6, 47, 110, 138 Archiv Manz, Stuttgard: 130, 131, 132l Herausgegeben von/Uitgegeven door Axel Föhl, Rheinisches Amt für Denkmalpflege, Arnold Lassotta, Andreas Oehlke, Siebe Rossel, Brauweiler: 7, 8, 9 Axel Föhl und Manfred Hamm: Industriegeschichte Hermann Josef Stenkamp und Ronald Stenvert des Textils: 119 Westfälisches Industriemuseum, Beltman Architekten en Ingenieurs BV, Enschede: Dortmund 2005 111, 112, 127oben, 128 Fischer: Besteming Semarang: 23u, 25lo Redaktion/Redactie Duncan Gurr and Julian Hunt: The cotton mills of Oldham: 37, 81r Hermann Josef Stenkamp Eduard Westerhoff: 56, 57 Hans-Joachim Isecke, TECCON Ingenieurtechnik, Zugleich Begleitpublikation zur Ausstel- Stuhr: 86 lung/Tevens publicatie bij de tentoonstelling John A. Ledeboer: Spinnerij Oosterveld: 100 des Westfälischen Industriemuseums John Lang: Who was Sir Philip Stott?: 40 Museum Jannink, Enschede: 19, 98 – Textilmuseum Bocholt, Museum voor Industriële Acheologie en Textiel, des Museums Jannink in Enschede Gent: 16oben und des Textilmuseums Rheine Ortschronik (Stadtarchiv) Rüti: 110 Peter Heckhuis, Rheine: 67u, 137 Publikation und Ausstellung ermöglichten/ Privatbesitz: 15, 25u, 26u, 30, 31, 46, 65, 66, 67oben, 83oben, 87oben, 88u, 88r, 90, 92, 125l Publicatie en tentoonstelling werden Rheinisches Industriemuseum, Schauplatz Ratingen: mogelijk gemaakt door 11, 17 Europäische Union Ronald Stenvert: 26r, 39r, 97, 113oben, 113r, 114, 125r, Westfälisches Industriemuseum 126 Kulturforum Rheine Roger N. -

Comments on Chadderton Partnership Neighbourhood Area and Forum Application for the Council's Response to the Key Issues Rais

Comments on Chadderton Partnership Neighbourhood Area and forum application For the council’s response to the key issues raised please see ‘Issues raised in relation to the Chadderton Partnership Neighbourhood Forum and Chadderton Neighbourhood area applications and Oldham Council’s response’ Full Name Organisation Application Comment Details that the comment relates to A Cadman Both I would like to formally object to the Chadderton Partnership. I feel that they have too many close ties to a political party to be objective and independent from government/ council agendas. After reading the constitution available of the Oldham.gov website, I feel that there is a large focus on development and I have grave concerns about further developments on greenbelt land within the Chadderton area. Furthermore I do not believe that one group can accurately represent a diverse population of 40,000+ residents. A neighbourhood group needs to be able to listen and respond to the residents for which is it representing. The Chadderton Partnership have not tried to community with residents of Chadderton about what their proposals are, and I fear that this is because they do not have their best interests at heart. A Cummings Both I would like to register my opposition to the Chadderton Partnership and to vote against the registration of the Focus Group (Neighbourhood Forum) with Oldham Council and the designation of the three Chadderton wards for consultation. This would not be appropriate nor is it in keeping with guidance. I feel that this would stop local residents from having their own legitimate local forums and independent voices.