Comparative Perspectives from Japan, China, and Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Checklist

Mountains and Rivers: Scenic Views of Japan, July 10, 2009-November 1, 2009 The landscape has long been an important part of Japanese art and literature. It was first celebrated in poetry, where invoking the name of a famous location, or meisho, was meant to summon a certain feeling. Later, paintings of these same locations would bring to mind their well-known poetic and literary history. Together, the poems and imagery comprised a canon of place and sentiment, as the same meisho were rendered again and again. During the Edo period (1603–1868) the landscape genre, initially available only to the elite, spread to the medium of woodblock printing, the art of commoner culture. In the 19th century, when most of the works in this exhibition were made, several factors led to the rise of the landscape genre in woodblock prints. Up to this time, the staples of the woodblock print medium had been images of beautiful courtesans and handsome kabuki theater actors. First among these factors was the rising popularity of domestic travel. The development of a system of major roads allowed many people to travel for both business and pleasure. Woodblock prints of locations along these travel routes could function as souvenirs for those who made the trip or as fantasy for those who could not. Rather than evoking a poetic past, these images of meisho were meant to tantalize viewers into imagining romantic far-off places. Another factor in the growth of the genre was the skill of two particular woodblock print artists— Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) (whose works are heavily represented here). -

Traditional Crafts of Kumamoto Various Traditional Crafts Are Used in Everyday Life in Kumamoto

Traditional Crafts of Kumamoto Various traditional crafts are used in everyday life in Kumamoto. These crafts are born from Kumamoto’s natural environment, the skills Traditional Crafts of Kumamoto of craftsmen, and the ingenuity used by locals in their daily lives. Kumamoto’s handicrafts are created through communication between Craft items that originate from Kumamoto and were handed down for the craft creators and the craft users. They are found in a variety of generations are designated “Traditional Crafts of Kumamoto.” To receive this places and used in a variety of ways. designated, the craft must be made using traditional techniques and must have over 30 years of history. There are about 90 such designated crafts in Kumamoto, including metalwork, ceramics, woodwork, bamboo crafts, dying and weaving, paper products, and traditional toys. Japan’s Nationally Designated Crafts To be deemed a “Nationally Designated Craft,” the traditional skills or techniques used to make the craft must have over 100 years of history, and must have developed in a fixed region with more than 10 organizations or 30 individual craftsmen currently engaged in the production of the craft. Over 200 crafts in Japan have been declared Nationally Designated Crafts, including Kyo and Arita ware pottery, and Wajima-style lacquerware. In Kumamoto, Shodai pottery, Amakusa ceramics, and Higo inlay metalwork all received this distinction in March 2003. In December 2013, Yamaga lanterns were the fourth craft from Kumamoto to be designated. 1 Higo-Zogan Metalwork Metalwork in Kumamoto includes the following crafts: Higo-zogan, which originated from sword accessories; Kawashiri and Hitoyoshi-Kuma cutting tools, such as kitchen knives, farm hoes and sickles; and swords, the production of which dates back 750 years ago to the Kamakura Period. -

The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection

NEWS RELEASE November, 2009 The Lineage of Culture – The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection The Tokyo National Museum is pleased to present the special exhibition “The Lineage of Culture—The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection” from Tuesday, April 20, to Sunday, June 6, 2010. The Eisei Bunko Foundation was established in 1950 by 16th-generation family head Hosokawa Moritatsu with the objective of preserving for future generations the legacy of the cultural treasures of the Hosokawa family, lords of the former Kumamoto domain. It takes its name from the “Ei” of Eigen’an—the subtemple of Kenninji in Kyoto, which served as the family temple for eight generations from the time of the original patriarch Hosokawa Yoriari, of the governing family of Izumi province in the medieval period— and the “Sei” of Seiryūji Castle, which was home to Hosokawa Fujitaka (better known as Yūsai), the founder of the modern Hosokawa line. Totaling over 80,000 objects, it is one of the leading collections of cultural properties in Japan and includes archival documents, Yūsai’s treatises on waka poetry, tea utensils connected to the great tea master Sen no Rikyū from the personal collection of 2nd-generation head Tadaoki (Sansai), various objects associated with Hosokawa Gracia, and paintings by Miyamoto Musashi. The current exhibition will present the history of the Hosokawa family and highlight its role in the transmission of traditional Japanese culture—in particular the secrets to understanding the Kokinshū poetry collection, and the cultural arts of Noh theater and the Way of Tea—by means of numerous treasured art objects and historical documents that have been safeguarded through the family’s tumultuous history. -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan Robert Goree, Wellesley College Abstract The cartographic history of Japan is remarkable for the sophistication, variety, and ingenuity of its maps. It is also remarkable for its many modes of spatial representation, which might not immediately seem cartographic but could very well be thought of as such. To understand the alterity of these cartographic modes and write Japanese map history for what it is, rather than what it is not, scholars need to be equipped with capacious definitions of maps not limited by modern Eurocentric expectations. This article explores such classificatory flexibility through an analysis of the mapping function of meisho zue, popular multivolume geographic encyclopedias published in Japan during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The article’s central contention is that the illustrations in meisho zue function as pictorial maps, both as individual compositions and in the aggregate. The main example offered is Miyako meisho zue (1780), which is shown to function like a map on account of its instrumental pictorial representation of landscape, virtual wayfinding capacity, spatial layout as a book, and biased selection of sites that contribute to a vision of prosperity. This last claim about site selection exposes the depiction of meisho as a means by which the editors of meisho zue recorded a version of cultural geography that normalized this vision of prosperity. Keywords: Japan, cartography, Akisato Ritō, meisho zue, illustrated book, map, prosperity Entertaining exhibitions arrayed on the dry bed of the Kamo River distracted throngs of people seeking relief from the summer heat in Tokugawa-era Kyoto.1 By the time Osaka-based ukiyo-e artist Takehara Shunchōsai (fl. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

Latest Japanese Sword Catalogue

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of December 23, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Upcoming Sword Shows & Sales Events Full details: http://new.uniquejapan.com/events/ 2013 YOKOSUKA NEX SPRING BAZAAR April 13th & 14th, 2013 kitchen knives for sale YOKOTA YOSC SPRING BAZAAR April 20th & 21st, 2013 Japanese swords & kitchen knives for sale OKINAWA SWORD SHOW V April 27th & 28th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN OKINAWA KAMAKURA “GOLDEN WEEKEND” SWORD SHOW VII May 4th & 5th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN KAMAKURA NEW EVENTS ARE BEING ADDED FREQUENTLY. PLEASE CHECK OUR EVENTS PAGE FOR UPDATES. WE LOOK FORWARD TO SERVING YOU. Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho x 2 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

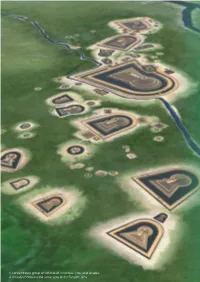

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

What Is Dewa Sanzan? the Spiritual Awe-Inspiring Mountains in the Tohoku Area, Embracing Peopleʼs Prayers… from the Heian Period, Mt.Gassan, Mt.Yudono and Mt

The ancient road of Dewa Rokujurigoegoe Kaido Visit the 1200 year old ancient route! Sea of Japan Yamagata Prefecture Tsuruoka City Rokujurigoe Kaido Nishikawa Town Asahi Tourism Bureau 60-ri Goe Kaido Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture The Ancient Road “Rokujuri-goe Kaido” Over 1200 years, this road has preserved traces of historical events “Rokujuri-goe Kaido,” an ancient road connecting the Shonai plain and the inland area is said to have opened about 1200 years ago. This road was the only road between Shonai and the inland area. It was a precipitous mountain road from Tsuruoka city to Yamagata city passing over Matsune, Juo-toge, Oami, Sainokami-toge, Tamugimata and Oguki-toge, then going through Shizu, Hondoji and Sagae. It is said to have existed already in ancient times, but it is not clear when this road was opened. The oldest theory says that this road was opened as a governmental road connecting the Dewa Kokufu government which was located in Fujishima town (now Tsuruoka city) and the county offices of the Mogami and Okitama areas. But there are many other theories as well. In the Muromachi and Edo periods, which were a time of prosperity for mountain worship, it became a lively road with pilgrims not only from the local area,but also from the Tohoku Part of a list of famous places in Shonai second district during the latter half of the Edo period. and Kanto areas heading to Mt. Yudono as “Oyama mairi” (mountain pilgrimage) custom was (Stored at the Native district museum of Tsuruoka city) booming. -

Migration and Networks in Early Modern Kyoto, Japanã

IRSH 47 (2002), pp. 243–259 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859002000597 # 2002 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Migration and Networks in Early Modern Kyoto, Japanà Mary Louise Nagata Summary: The question of assimilation networks for migrants is usually applied to international migration. In this study, however, I use the population registers for a neighborhood in early modern Kyoto to look for possible network connections in domestic migration. I found a yearly turnover of fourteen households moving in and out of the neighborhood. Household and group migration was more important than individual migration and there is some sign of primary–secondary migration flows. Service migration did not play a major role in the migration patterns of this neighborhood, but the textile industry was probably an important attraction. Evidence of networks appears in the use of shop names that reflect a connection with a province or some specific location. These shop names usually reflected the place of origin of the household and may have been an effective method of gaining network connections and the guarantors necessary for finding housing and employment. INTRODUCTION The study of assimilation networks is a major topic in the study of international migration. The immigrant, far from home and often speaking a language different from the local population, frequently relies upon a network of contacts to settle into his new home. This network is often a local subcommunity with ties to the home country of the immigrant and shares language, culture, and religious affiliations with the immigrant. Such networks often help the immigrant find housing, employment and access to essential services that facilitate his survival and assimilation into the new community.1 While assimilation networks are an important aspect of the study of à I was able to collect this data with the support of the EurAsian Project on Population and Family History, under the leadership of Akira Hayami at International Research Center for Japanese Studies, with the help of Kiyoshi Hamano. -

Japan in the Meiji

en Japan in the Meiji Era The collection of Heinrich von Siebold Galleries of Marvel Japan in the Meiji Era Japan in the Meiji Era The collection of The collection of Heinrich von Siebold Heinrich von Siebold This exhibition grew out of a research Meiji period (1868–1912) as a youth. Through project of the Weltmuseum Wien in the mediation of his elder brother Alexan- co-operation with the research team of der (1846–1911), he obtained a position as the National Museum of Japanese History, interpreter to the Austro-Hungarian Diplo- Sakura, Japan. It is an attempt at a reap- matic Mission in Tokyo and lived in Japan praisal of nineteenth-century collections for most of his life, where he amassed a of Japanese artefacts situated outside of collection of more than 20,000 artefacts. He Japan. The focus of this research lies on donated about 5,000 cultural objects and Heinrich von Siebold (1852–1908), son of art works to Kaiser Franz Joseph in 1889. the physician and author of numeral books About 90 per cent of the items pictured in Hochparterre on Japan Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796– the photographs in the exhibition belong to 1866). Heinrich went to Japan during the the Weltmuseum Wien. Room 1 Ceramics and agricultural implements Room 2 Weapons and ornate lacquer boxes Room 3 Musical instruments and bronze vessels Ceramics and Room 1 agricultural implements 1 The photographs show a presentation of artefacts of the Ainu from Hokkaido, togeth- This large jar with a lid is Kutani ware from dynasty (1638–1644) Jingdezhen kilns, part of Heinrich von Siebold’s collection from er with agricultural and fishing implements Ishikawa prefecture.