Participat Managieme in Sri Lanka's Irrigation Schemes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treadmill Operation

Adventure 1 Adventure 5 Adventure 3 Adventure 7 OPERATION GUIDE TREADMILL OPERATION This section explains how to use your treadmill’s console and programming. The BASIC OPERATION section in the TREADMILL GUIDE has instructions for the following: • LOCATION OF THE TREADMILL • USING THE SAFETY KEY • FOLDING THE TREADMILL • MOVING THE TREADMILL • LEVELING THE TREADMILL • TENSIONING THE RUNNING BELT • CENTERING THE RUNNING BELT • USING THE HEART RATE FUNCTION 2 3 K H M D A O E I ADVENTURE 1 CONSOLE OPERATION Note: There is a thin protective sheet of clear plastic on the overlay of the console that should be removed before use. A) LED DISPLAY WINDOW: time, distance, speed, calories, incline and heart rate. B) START/PAUSE KEY: press to start workout and pause workout. Time Distance Adventure 1 Zeit Entfernung C) STOP KEY: press to stop workout. Hold to reset console. Adventure 1 ENERGYSAVER Energiesparmodus Incline Speed Steigung Geschwindigkeit D) PROGRAM KEYS: press to select workout. Calories Kalorien E) ENTER KEY: press to confirm selection during programming setup. Heart Rate Herzfrequenz Programs Programme : press to adjust incline level. Enter F) INCLINE KEYS Eingabe Change Classic Calories Distance HRC Custom Display Klassisch Kalorien Entfernung Benutzer Anzeigenwechsel G) SPEED KEYS: press to adjust speed level. Quick Incline Keys 4 km/h 8 km/h 12 km/h 16 km/h 18 km/h Quick Speed Keys 2 % 4 % 6 % 8 % 10 % Direktwahl Geschwindigkeit Direktwahl Steigung 3 mph 5 mph 8 mph 10 mph 11 mph H) INCLINE QUICK KEYS: used to reach desired incline quickly. ADVENTURE1 I) SPEED QUICK KEYS: used to reach desired speed quickly. -

Dress Fashions of Royalty Kotte Kingdom of Sri Lanka

DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA . DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. Dedication First Edition : 2017 For Vidyajothi Emeritus Professor Nimal De Silva DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KingDOM OF SRI LANKA Eminent scholar and ideal Guru © Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne ISBN 978-955-30- Cover Design by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd Page setting by: Nisha Weerasuriya Published by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. 661/665/675, P. de S. Kularatne Mawatha, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka. Printed by: Chathura Printers 69, Kumaradasa Place, Wellampitiya, Sri Lanka. Foreword This collection of writings provides an intensive reading of dress fashions of royalty which intensified Portuguese political power over the Kingdom of Kotte. The royalties were at the top in the social strata eventually known to be the fashion creators of society. Their engagement in creating and practicing dress fashion prevailed from time immemorial. The author builds a sound dialogue within six chapters’ covering most areas of dress fashion by incorporating valid recorded historical data, variety of recorded visual formats cross checking each other, clarifying how the period signifies a turning point in the fashion history of Sri Lanka culminating with emerging novel dress features. This scholarly work is very much vital for university academia and fellow researches in the stream of Humanities and Social Sciences interested in historical dress fashions and usage of jewelry. Furthermore, the content leads the reader into a new perspective on the subject through a sound dialogue which has been narrated through validated recorded historical data, recorded historical visual information, and logical analysis with reference to scholars of the subject area. -

NATIVE SAML SUPPORT for SSO FFTH – RSA Archer 6.8

▪ Dell Customer Communication - Confidential NATIVE SAML SUPPORT FOR SSO FFTH – RSA Archer 6.8 1 ▪ Dell Customer Communication - Confidential AGENDA NATIVE SAML 2.0 SUPPORT FOR SSO ▪ Background ▪ Overview ▪ Troubleshooting ▪ Demo 2 ▪ Dell Customer Communication - Confidential BACKGROUND ▪ Main Goal: Provide native SAML 2.0 support for SSO to RSA Archer platform ▪ Prior To 6.8, RSA Archer could not process SAML 2.0 assertions natively ▪ Required using ADFS as middleware to convert SAML assertions to Windows Federated claims ▪ Increased complexity of enabling integration with SAML IDP ▪ Security concerns with ADFS served as an implementation roadblock ▪ Enabling native processing of SAML assertions eliminates the need for ADFS 3 ▪ Dell Customer Communication - Confidential OTHER GOALS ▪ Support multiple SAML identity providers for a single instance ▪ Provide vanity URLs to automatically redirect to a specific identity provider ▪ Provide Service Provider metadata for easier setup in identity provider ▪ Support automatic user provisioning ▪ Support user profile, group membership, and role assignment updates via SSO ▪ Improved logging to aid in troubleshooting authentication issues − Errors point to specific log reference in stand-alone SAML log file − Info level logging provides entire request and assertion contents ▪ Leave Federation SSO option as is 4 ▪ Dell Customer Communication - Confidential OVERVIEW 5 ▪ Dell Customer Communication - Confidential CONFIGURING SAML SSO ▪ SAML SSO is enabled by selecting the new SAML Single Sign-On Mode -

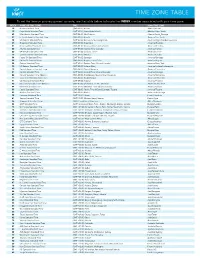

Time Zone Table

TIME ZONE TABLE To set the time on your equipment console, use the table below to locate the INDEX number associated with your time zone. INDEX NAME OF TIME ZONE TIME IANA TIME ZONE 10 Azores Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Azores Atlantic/Azores 12 Cape Verde Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Cape Verde Islands Atlantic/Cape_Verde 43 Mid-Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-02:00) Mid-Atlantic Atlantic/South_Georgia 27 E. South America Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Brasilia America/Sao_Paulo 58 SA Eastern Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Buenos Aires, Georgetown America/Argentina/Buenos_Aires 35 Greenland Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Greenland America/Godthab 51 Newfoundland Standard Time (GMT-03:30) Newfoundland and Labrador America/St_Johns 06 Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Atlantic Time (Canada) America/Halifax 60 SA Western Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Caracas, La Paz America/La_Paz 17 Central Brazilian Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Manaus America/Cuiaba 54 Pacific SA Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Santiago America/Santiago 59 SA Pacific Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Bogota, Lima, Quito America/Bogota 28 Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time (US and Canada) America/New_York 70 US Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Indiana (East) America/Indiana/Indianapolis 15 Central America Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central America America/Costa_Rica 21 Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central Time (US and Canada) America/Chicago 22 Central Standard Time (Mexico) (GMT-06:00) Guadalajara, Mexico City, Monterrey America/Monterrey 11 Canada Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Saskatchewan -

Service Bulletin: Viafit 2.0 Supplement Sheet

Service Bulletin: ViaFit 2.0 Supplement Sheet Prepared by: Date Prepared: Regina Templeton 9/23/2015 Models Affected: Elite T7 PROBLEM A limited number of new treadmills with ViaFit 2.0 software have been sent to customers. The cartons were missing a supplement sheet highlighting changes from the v1.0 software. The serial numbers of these treadmills are listed on the following page. SOLUTION The attached 4-page supplement sheet should be used in place of pages 8 and 9 in the OPERATION GUIDE. The supplement sheet is now being included in the carton, and it is also posted on the Horizon website. Treadmill Serial Numbers Container Number Serial Number TM4751505CC00001-TM4751505CC00007 TM4751505CC00009-TM4751505CC00012 TM4751505CC00014-TM4751505CC00027 TM4751505CC00030-TM4751505CC00041 TM4751505CC00043-TM4751505CC00054 GESU5188024 TM4751505CC00057-TM4751505CC00058 TM4751505CC00060-TM4751505CC00070 TM4751505CC00073-TM4751505CC00083 TM4751505CC00085-TM4751505CC00086 TM4751505CC00090-TM4751505CC00098 TM4751507CA00099-TM4751507CA00113 FCIU9814414 TM4751507CB00197-TM4751507CB00294 TGHU6676427 TM4751507CA00001-TM4751507CA00098 TM4751508CB00006 TM4751508CB00010-TM4751508CB00023 TM4751508CB00028 TM4751508CB00044 TM4751508CB00050 CBHU8429138 TM4751508CB00054-TM4751508CB00105 TM4751508CB00107-TM4751508CB00110 TM4751508CB00112-TM4751508CB00115 TM4751508CB00145 TM4751508CB00161 TM4751508CB00179-TM4751508CB00196 TM4751508CB00197-TM4751508CB00220 TM4751508CB00235-TM4751508CB00242 TM4751508CB00251-TM4751508CB00256 TM4751508CB00305-TM4751508CB00313 TM4751508CB00315-TM4751508CB00322 -

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: Second Integrated Road Investment Program

Second Integrated Road Investment Program (RRP SRI 50301-001) Facility Administration Manual Project Number: 50301-001 MFF number: xxxx 10 August 2017 Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: Second Integrated Road Investment Program ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CRC – conventional road contract DMF – design and monitoring framework EARF – environmental assessment and review framework EMP – environmental management plan ESDD – Environment and Social Development Division EWCD – elderly, women, children, and disabled FIDIC – International Federation of Consulting Engineers GAP – gender action plan ICB – international competitive bidding IEE – initial environmental examination IPP – indigenous peoples plan IPPF – indigenous peoples planning framework iRoad 2 – Second Integrated Road Investment Program MFF – multitranche financing facility MOHEH – Ministry of Higher Education and Highways NCB – national competitive bidding PBM – performance-based maintenance PFR – periodic financing request PIC – project implementation consultant PIU – project implementation unit PPMS – project performance management system RDA – Road Development Authority RRP – report and recommendation of the President SAPE – survey and preliminary engineering SLRs – Sri Lanka rupees SOE – statement of expenditure CONTENTS I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. IMPLEMENTATION PLANS 1 A. Project Readiness Activities 1 B. Overall Project Implementation Plan 3 III. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 4 A. Project Implementation Organizations: Roles and Responsibilities 4 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 5 C. Project Organization Structure 6 IV. COSTS AND FINANCING 12 A. Cost Estimates Preparation and Revisions 13 B. Key Assumptions 13 C. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category and Financier – Facility 14 D. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds for Tranche 1 16 E. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year 17 F. Contract and Disbursement S-Curve 18 G. -

Performance Report and Annual Accounts 2018

Performance Report 2018 PERFORMANCE REPORT AND ANNUAL ACCOUNTS 2018 MEASUREMENT UNITS, STANDARDS AND SERVICES DEPARTMENT 1 Performance Report 2018 CONTENT MESSAGE OF THE DIRECTOR.……………………………………………………...5 VISION………………………………………………………………………………….....7 MISSION…………………………………………………………………………………..7 OBJECTIVES……………………………………………………………………………..7 01.Introduction 1.1The Department and Its Functions………………………………………………8 1.2 Metrology …………………………………………………………………….....10 02. MUSSD as the Apex Institution for Metrology in Sri Lanka 2.1 Activities of Scientific Metrology…………………………………………........11 2.1.1 National Measurement Laboratory (NML)……………… ………...11 2.1.2 Establishment of Traceability………………………………………..12 2.1.3 Participation of inter-laboratory comparison………………………13 2.1.4 Maintenance of SI units……………………………………................13 2.1.5 Generation and Broadcasting the Standard Time of Sri Lanka…..15 2.1.6 Research and Developments……………………………………........16 2.2 Activities of Industrial Metrology……………………………………………..17 2.2.1 Industrial Calibrations……………………………………………….17 2.2.2 Training and Consultancy……………………………………............22 2.3 Activities of Legal Metrology…………………………………………………..22 2.3.1 Re-verification of Working Standards……………………………....23 2.3.2 Pattern Approvals………………………………………………….....23 2.3.3 Verifications, Inspections, and Raids of Weighing and Measuring Instruments Conducted on District Basis…………………………...24 2.3.4 Inspection of Pre-Packed Commodities……………………………..34 2.3.5 Registration of Private Entrepreneurs Engaged in Commercial Activities Controlled Over Legal -

Oracle Hyperion Data Relationship Management Web Service API Developer's Guide

Oracle® Hyperion Data Relationship Management, Fusion Edition Release 11.1.2.2.000 Web Service API Developer's Guide Overview ............................................................................................................................... 2 About the Data Relationship Management Web Service ........................................................ 2 Using the Data Relationship Management Web Service ......................................................... 3 Time Zone IDs ..................................................................................................................... 4 Using JDeveloper to Create a Web Service Client .................................................................. 6 New Features in This Release ................................................................................................ 6 Methods .............................................................................................................................. 6 Types .................................................................................................................................. 6 Upgrading Existing API Programs ......................................................................................... 7 Upgrading 11.1.2.1 API Programs ....................................................................................... 7 Changes to Existing Types....................................................................................................... 7 Regenerating Web Service Proxy Classes ................................................................................. -

Production Loss Analysis

Production Loss Analysis © 2020 General Electric Company Contents Chapter 1: Overview 1 Overview of the Production Loss Analysis (PLA) Module 2 Access the PLA Overview Page 3 PLA Workflow 4 Chapter 2: Workflow 6 Product Workflow 7 Define Codes 8 Define Products 8 Define Production Unit 8 Define Production Profile 8 Create Plan Templates 8 Create Production Plan (Manual/Time/Quantity/Template) 8 Enter Production Data 8 Reconcile Production Losses 9 Create Production Event 9 Assign Causing Asset 9 Other Workflows 9 Root Cause Analysis (RCA) 9 Integrate with M2M Data Source 9 Policy Designer: Design Policy 9 Chapter 3: Production Data 10 About Production Data 11 Access a Production Data Record 13 Access the Losses Associated with a Production Data Record 14 Access the Losses Associated with a Production Plan 14 Color Coding for Unaccounted Loss 15 Create a Production Loss 16 Tolerance Limit of the Planned Production 18 ii Production Loss Analysis Modify a Production Data Record 19 Modify a Production Loss 19 Reconcile Production Data and Losses in Bulk 20 Copy the Production Losses 23 Delete a Loss via the Production Data Workspace 24 Delete the Losses via the Production Losses Workspace 25 Chapter 4: Production Plans 26 About Production Plans 27 About Usage of the Planned Production Values 27 About the Short Range Plan 29 Access a Production Plan 29 Access the Production Summary 31 Create a Production Plan Using the Production Plan Builder 33 Create a Production Plan from a Plan Template 37 Create a Manual Production Plan 41 Modify a Manual -

Eli 10 12-Lead Resting Electrocardiograph User Manual

REF 9515-170-50-ENG Rev H1 ELI 10 12-LEAD RESTING ELECTROCARDIOGRAPH USER MANUAL Manufactured by Mortara Instrument, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin U.S.A. CAUTION: Federal law restricts this device to sale by or on the order of a physician. Copyright © 2015 by Mortara Instrument, Inc. 7865 N. 86th Street Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53224 This document contains confidential information that belongs to Mortara Instrument, Inc. No part of this document may be transmitted, reproduced, used, or disclosed outside of the receiving organization without the express written consent of Mortara Instrument, Inc. Mortara is a registered trademark of Mortara Instrument, Inc. E-Scribe, ELI, and VERITAS are trademarks of Mortara Instrument, Inc. Cisco® is the registered trademark of Cisco Systems, Inc. Microsoft® and Windows™ are trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. DICOM® is the registered trademark of the National Electrical Manufacturers Association for its standards publications relating to digital communications of medical information. V1.13. TECHNICAL SUPPORT AND SERVICE Headquarters Sales Support/ Supplies & Accessories Mortara Instrument, Inc. 7865 North 86th Street Mortara Instrument, Inc. Milwaukee, WI 53224 7865 North 86th Street U.S.A. Milwaukee, WI 53224 Tel: 414.354.1600 U.S.A. Tel: 800.231.7437 Tel: 414.354.1600 Fax: 414.354.4760 Fax: 414.354.4760 Internet: http://www.mortara.com Hospital Customers: [email protected] Physician Practice: [email protected] European Union U.S. Distribution: [email protected] Representative Mortara Instrument Germany Bonifaciusring 15 Mortara Instrument Europe, s.r.l. 45309 Essen (European Headquarters) Germany Via Cimarosa 103/105 Tel: +49.201.18 55 69 70 40033 Casalecchio di Reno (BO) Fax: +49.201.18 55 69 77 Italy Tel: +39.051.298.7811 Mortara Instrument Netherlands Fax: +39.051.613.3582 Postbus 324 5680 AH Best Industrieweg 160b Service/Technical 5683 CG Best Support Group Netherlands Tel: +31.499.377310 Mortara Instrument, Inc. -

Meridium APM AMS Analytics

Meridium APM AMS Analytics Meridium APM AMS Analytics 3.6.1.1.0 Confidential and Proprietary Information of Meridium, Inc. • Page 1 of 189 Copyright and Legal Meridium APM AMS Analytics 3.6.1.1.0 Copyright © Meridium, Inc. 2017 All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. This software/documentation contains proprietary information of Meridium, Inc.; it is provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure. All rights including reproduction by photographic or electronic process and translation into other languages of this material are fully reserved under copyright laws. Repro- duction or use of this material in whole or in part in any manner without written per- mission from Meridium, Inc. is strictly prohibited. Meridium is a registered trademark of Meridium, Inc. All trade names referenced are the service mark, trademark or registered trademark of the respective manufacturer. Confidential and Proprietary Information of Meridium, Inc. • Page 2 of 189 About This Document About This Document This file is provided so that you can easily print this section of the Meridium APM Help system. You should, however, use the Help system instead of a printed document. This is because the Help system provides hyperlinks that will assist you in easily locating the related instructions that you need. Such links are not available in a print document format. The Meridium APM Help system can be accessed within Meridium APM itself or via the Meridium APM Documentation Website (https://www.me- ridium.com/documentation/WebHelp/WebHelpMaster.htm). Note: If you do not have access to the Meridium APM Documentation Website, con- tact Meridium Global Support Services. -

Replicon Data Import Utility User Guide

TimeAttend TimeCost TimeBill TimeOff Replicon WebExpense Data Import Utility Version 8.27 USER GUIDE Notices © 2006‐2012 Replicon, Inc. All rights reserved. All parts of this document are the property of Replicon Inc. No part of this document may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever including me‐ chanical or electronic media such as disk or tape. No part of this document may be transmitted in any form by any means without the prior written permission of Replicon Inc. Replicon, Web Resource, and Web TimeOff and associated logos are trademarks of Replicon, Inc. Other product or service names mentioned in this document may be trademarks of Replicon, or of the respective owners of those trademarks. This document may include links to websites not owned or managed by Replicon, Inc. Note that every effort has been made at the time of release to ensure all links provided are valid. However, Replicon makes no guarantee that the links will continue to be valid in the future. Additionally, Rep‐ licon is not responsible for the information included in these websites and provides no guarantees or warranties regarding the accuracy of this in‐ formation. Revision 08/15/12 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Welcome .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 About the Replicon Data Import Utility...........................................................................................................................................................