Theard-Thesis-Final April 7 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lee Quiñones Black and Blue Lee Quiñones Black and Blue

LEE QUIÑONES BLACK AND BLUE LEE QUIÑONES BLACK AND BLUE Charlie James Gallery is very proud to present Black and Blue, our second solo show with New York-based artist Lee Quiñones. The exhibition takes its name from the show’s centerpiece painting that focuses on our collective witness to the horrific murder of George Floyd on May 25th, 2020, and in a subliminal way, reminds us of the continual silencing of black and brown voices across generation and geography, figures such as Stephen Biko in room 619 and the countless souls abducted in America’s original sin of 1619. The Black and Blue piece makes clear reference to mobile phone technology and to the gravitational pull of social media that we all use in some shape or form every day of our lives. Aside from its semi hidden central figures, Black and Blue contains an array of 569 individually painted I-phone screens, one for each second of the 9 minute 29 second video that marked the murder of Floyd. The painting sets the tone for the rest of the show which features paintings and drawings dealing with historical social justice fault lines, from the desegregation of Little Rock Central High in Little Rock, AR to the ongoing displacement of Native Americans. These new works are conceived around plays on common phrases such as “Loss for words” becoming “Lost for words” and derogatory statements such as “Get Off My Lawn!” countered with “Get Off My Dawn!” Supporting the political nucleus of the show, Lee will present a suite of “bombed” canvas paintings – expressive pieces acknowledging Lee’s graffiti roots executed in a paint booth fashioned within Lee’s studio. -

ON the RECORD: a Conversation with Directors Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering

ON THE RECORD Directed by Kirby Dick & Amy Ziering USA / 2020 / 97 mins Press Contacts Sales Contact - UTA Ryan Mazie, 609-410-2067 Rena Ronson, [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS With their groundbreaking films on sexual assault in the military (The Invisible War) and on college campuses (The Hunting Ground), directors Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering shook the established view of sexual assault in America, moving it from an isolated “he said-she said” narrative to a sweeping indictment of systemic violence and rape culture. Now, in the #MeToo era that their films helped to usher in, comes ON THE RECORD, their third documentary in the trilogy. A searing examination of the costs of coming forward, the film follows Drew Dixon as she wrestles with the decision to go public and share her story with the NYTimes. ON THE RECORD takes you into the world of Def Jam Records in the ‘90s, where Dixon was a rising star in an industry rife with misogyny and sexual harassment. As Dixon recounts in the film, from her first day on the job, she managed to deflect and move past ongoing harassment, until she was wholly caught off guard one fateful night and brutally accosted by Simmons. More than two decades later, ON THE RECORD documents the devastating toll this recounted act exacted not only on Drew’s life but on the lives of several other women who describe having been assaulted by Simmons. Deeply illuminating and packed with powerful and revelatory insights, ON THE RECORD’s narrative tale is punctuated by interviews with prominent black thought leaders, activists, journalists and academics, who speak about the unique binds African-American women face when dealing with sexual violence in a society still plagued by racism. -

Silenciados the Voice of the Voiceless

LA VOZ DE LOS SILENCIADOS THE VOICE OF THE VOICELESS A film by Maximón Monihan SYNOPSIS "Chaplin meets Eraserhead” in this magical-neo-realist, modern day silent film. LA VOZ DE LOS SILENCIADOS takes us inside the mind and heartbreak of Olga, a deaf teenager brought from Latin America to New York City, under the false promise of attending a “Christian Sign Language School”. Upon arrival we enter a world of immigrant trafficking, and life is turned upside-down as she's enslaved by an international criminal ring. Forced to beg on the subway, Olga uses courage, cunning, and even humor, to face an unimaginable nightmare-on-loop that ravages the audience. Based on a real case broken by the NYPD. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT For years I had been noticing deaf people on the subway selling I read about this in the newspapers and became obsessed with trinkets. In a New York overloaded with in-your-face, aggressive telling this story to the public. The news came and went in one busy panhandling as performance art, my interactions with the deaf week– people moved on, I didn’t. I kept coming back to the story, trinket-peddlers were eye-raising moments. The person would put consumed with sharing what I believe is the perfect allegory for the trinket down next to you, and trust that by the time they human greed. A decade later, the film is finally in front of you. returned from the other end of the train, you had read the card– the one that said, “I am deaf. -

Lee Quiñones Selected Works

LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS ).'82/+0'3+9-'22+8? LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Year of the Dragon Archival pigment print 20 x 28.75 inches unframed Edition of 30 2019 Printed at Supreme Digital, Brooklyn NY On Epson Hot Press Bright 330 GSM Paper TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Voices Carry Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker, ink and pencil on Navy Issue plywood panels 94.5 x 105 inches 1940s-1996-2005 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tranquility of an exit Acrylic, oil, Spray paint, Paint marker and ink on Navy Issue plywood panels 42 x 48 inches 1940s-1996-2005 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 2 Acrylic, Spray paint and ink on gypsum panel 15 x 21 inches unframed 2005-2018 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 3 Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker and ink on gypsum panel 20 x 30 inches unframed 2005-2018 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 6 Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker, ink and pencil on gypsum panel 14.75 x 20.75 inches unframed 2005-2018 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 7 Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker, ink and pencil on gypsum panel 24 x 33.25 inches unframed 2005-2018 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 8 Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker, ink and pencil on gypsum panel 20 x 30 inches unframed 2005-2018 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 9 Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker on gypsum panel 20.5 x 30 inches unframed 2005-2018 TABLETS LEE QUIÑONES SELECTED WORKS Tablet # 10 Acrylic, Spray paint, Paint marker, ink and pencil on gypsum -

Look Inside (Pdf)

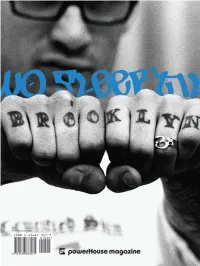

issue 1 i NO Sleep til ABLE OF CONTENTS 10 QUIK t 11 Letter from the Editor 13, 15 Contributors 16, 58 Delphine Fawundu-Buford 18, 57 Back in the Days by Jamel Shabazz 20 Public Access by Ricky Powell 22 Street Play by Martha Cooper, Text by Carlos “MARE 139” Rodriguez 26 Crosstown by Helen Levitt 27 Slide Show by Helen Levitt 28, 56 A Time Before Crack by Jamel Shabazz 30 Lisa Kahane 32 The Breaks: Kickin’ It Old School 1982–1990 by Janette Beckman 34 FUN! The True Story of Patti Astor, Photo by Martha Cooper 36 Carol Friedman 38 Wild Style: The Sampler by Charlie Ahearn 40 Ricky Powell Meets DR.REVOLT 42 Enduring Justice by Thomas Roma 44 It’s All Good by Boogie, Text by Tango 46 Peter Beste 48 Mark Peterson 50 Chris Nieratko 52 Q. Sakamaki 54 Carlos “MARE 139” Rodriguez, Text by Henry Chalfant 56 Miss Rosen 59 LADY PINK 60 TOOFLY 64 Autograf: New York City’s Graffiti Writers by Peter Sutherland 66 Subway Art by Henry Chalfant 68 BL .ONE, DG JA, JERMS, SLASH 70 Bombshell: The Life and Crimes of Claw Money, Text by MISS 17 72 We B*Girlz by Martha Cooper, Text by Rokafella 76 Ricky Powell, Portrait by Craig Wetherby 78 Charles Peterson 80 Burgerworld: Inside Hamburger Eyes 82 KEL 1ST 83 DAZE aka Chris Ellis 84 Infamy: Interview with Doug Pray 86, 89 We Skate Hardcore by Vincent Cianni 88, 90 East Side Stories: Gang Life in East L.A. by Joseph Rodríguez 92 NATO 94 Brooklyn Kings: New York City’s Black Bikers by Martin Dixon 104 Fletcher Street by Martha Camarillo lETTER FROM THE EDITOR I grew up on the wrong side of the Bronx… “don’t stop,” but at the time I was pretty damn sure I was Lisa Bonet on The Cosby Show. -

Publications and Films

Public Collections Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York, NY The Whitney Museum, New York, NY Tuscan Sun Festival, Cortona Italy Gwacheon National Science Museum, Seoul, Korea Statsbibliothek, Munich, Germany Klingspor Museum, Affenbach, Germany Raimund Thomas, Munich Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen Dannheisser Foundation, NY Frederick R. Weisman Foundation, Los Angeles Mark Twain Bankshares, St. Louis Museum of Modern Art, NY Chase Manhattan N.A., New York The Brooklyn Museum, New York The Paterson Museum, New Jersey Gronniger Museum, Gronnigen, The Netherlands The Federal Reserve, Washington, DC Museum of the City of New York, New York Speerstra Foundation, Apples, Switzerland Smithsonian National Museum for African American History and Culture, Washington, DC The Addison Gallery of American Art at the Phillips Academy, Andover, MA The Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT The Bronx Museum of Art, Bronx, NY Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY Books and Catalogues 2020 “40 Yeards of Creation”, solo exhibition catalogue, Ghost Galerie text by Caroline Pozzo di Borgo, Christian Omodeo “Next Wave”, solo exhibition catalogue, Cahier d’Art de I’ICT, Institute Catholique de Toulouse “Contrast” by Karski and Friends 2019 “Seasons” solo exhibition catalogue, Galleria del Palazzo, text by Vittorio Scarbi, Beba Marsno “Beyond the Streets” catalogue, compiled by Roger Gastman “UPAW, Urban Painting Around the World”, Monaco catalogue 2018 “Portals”, solo exhibition catalogue, Speerstra Galerie “Beyond the Streets”, -

Reggie Yates

-Olympic Special -Red Hot -Reggie Yates -Immortal Technique -Road to Carnival -Micachu - Basking in LDN Tropical Ronnie Grebenyuk Askwasi Tawai Poku The Cut welcomed new members to the New Issue, New beginnings. It’s been great team and for the last couple of months working on this edition as we as a team truly we have been very busy working together have learnt a lot and can’t thank the people on the jam-packed summer issue with that made this happen any more! We’ve got everything from Beijing hopefuls to new a massive sports and music section which and upcoming talent from Andrea Crewes will keep your eyes and minds occupied in Paris to grime sensation Red Hot and for a hot minute. So stop everything you much more, also exclusives from Reggie are doing, Cancel all you meetings, links Yates and Immortal and appointments and Technique all made by get ready to indulge young people. With a your lives into the cut The Cut Newspaper lot of positive feedback magazine.Have a fun The Stowe Centre from the 1st issue and safe summer and 258 Harrow Road London W2 5ES we decided to make enjoy reading The Cut. The Cut even more For exciting news as [email protected] superior with almost it happens from The www.thecutnewspaper.com double the content to Cut Team visit www. last you all summer. thecutnewspaper.com This issue is fresh like a cool drink... We have exclusive interviews with outstanding Olympic The latest news from The Cut Interviews with the starts of the blockbusting film talent, from gold medallist Graham Edmunds to 14 year Taekwondo wonderkid Tom Smith. -

Hip-Hop and Rap Resources for Music Librarians Author(S): Andrew Leach Source: Notes, Second Series, Vol

"One Day It'll All Make Sense": Hip-Hop and Rap Resources for Music Librarians Author(s): Andrew Leach Source: Notes, Second Series, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Sep., 2008), pp. 9-37 Published by: Music Library Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30163606 Accessed: 23-09-2015 13:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Music Library Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Notes. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 138.16.114.93 on Wed, 23 Sep 2015 13:21:48 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions "ONE DAY IT'LL ALL MAKESENSE": HIP-HOP AND RAP RESOURCESFOR MUSIC LIBRARIANS BY ANDREW LEACH 0 Despite being an object of derision within academia for many years, the study of hip-hop culture and rap music has now largely gained re- spectability in the academy, and is considerably less marginalized than it was only a decade ago. Scholars working in a number of disciplines are increasingly recognizing hip-hop culture and rap music as subjects wor- thy of attention. Consequently, a great deal of scholarly study and writing on hip-hop and rap is being carried out, drawing from fields including African American studies, history, linguistics, literature, musicology, soci- ology, and women's studies. -

Visual Literacy (Images and Photographs) Every Day, We See and Are Exposed to Hundreds, Perhaps Thousands, of Images That Pass Through Our Radar Screens

Visual Literacy (Images and Photographs) Every day, we see and are exposed to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of images that pass through our radar screens. Everyone, it seems, is vying for our attention. Unfortunately, not many of us know how to "read images.’ One of the ways to teach critical thinking and "media literacy" is to start with the still image. In many arts classrooms, “visual literacy” is introduced: the methods and techniques artists use to create meaning in paintings: that knowledge can now be applied to photographs as well. SC State Department of Education Visual & Performing Arts Standards (link to 2010 revision) 2010 Media Arts Standard Standard 3 (Media Literacy): The student will demonstrate the ability to access, analyze, interpret and create media (communications) in all forms. Teachers will recognize “analyze,” “interpret” and “create” as three of the verbs belonging to the Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning higher order thinking skills. Analyze (or analysis) is defined as: “breaking down objects or ideas into simpler parts and seeing how the parts relate and are organized” (source) Interpret is defined as: “to bring out the meaning of” whatever is seen (source) Creating is defined as: “putting the elements together to form a coherent or functional whole; reorganising elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning or producing” (Source) Creating sits at the top a new Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy. Take a look (see page 6 in the hyperlinked document) at all of the various ways your students can create media -

Icons of Hip Hop: an Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, Volumes 1 & 2

Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, Volumes 1 & 2 Edited by Mickey Hess Greenwood Press ICONS OF HIP HOP Recent Titles in Greenwood Icons Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: An Encyclopedia of Our Worst Nightmares Edited by S.T. Joshi Icons of Business: An Encyclopedia of Mavericks, Movers, and Shakers Kateri Drexler ICONS OF HIP HOP An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, And Culture VOLUME 1 Edited by Mickey Hess Greenwood Icons GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut . London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Icons of hip hop : an encyclopedia of the movement, music, and culture / edited by Mickey Hess p. cm. – (Greenwood icons) Includes bibliographical references, discographies, and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33902-8 (set: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33903-5 (vol 1: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33904-2 (vol 2: alk. paper) 1. Rap musicians—Biography. 2. Turntablists—Biography. 3. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. 4. Hip-hop. I. Hess, Mickey, 1975– ML394. I26 2007 782.421649'03—dc22 2007008194 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright Ó 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007008194 ISBN-10: 0-313-33902-3 (set) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33902-8 (set) 0-313-33903-1 (vol. 1) 978-0-313-33903-5 (vol. 1) 0-313-33904-X (vol. 2) 978-0-313-33904-2 (vol. -

Fall 2010 Catalog Dear Powerhouse Follower—

We can no longer build brands, we can only move people. We can no longer position brands, we can only create dialogues between people and brands based on a brand’s human purpose. We can no longer rely on ads that speak to people, we must provide people with opportunities to act. — from , see p.2 powerHouse Books is proud to distribute: Fall 2010 Catalog Dear powerHouse follower— You are, with any luck, a retailer, a reviewer, a promoter, or just someone vigorously involved in the visual arts, and have been following us through our www.powerHouseBooks.com TABLE OF CONTENTS FALL 2010 varied publications over the years and the copious press we made with them, and perhaps recall the risks, the successes, maybe even the élan to which we aspired in bringing to market interesting artists’ visual ideas and narratives in this lonely practice of independent illustrated book publishing... POWERHOUSE BOOKS You have witnessed many changes over the years: you’ve seen us produce era- 2–5 HUMAN KIND ......................................................by Tom Bernardin, CEO and Mark Tutssel, CCO Leo Burnett 6–7 CAT PRINT a VICE Books title . .by Takako Iwasa defining tomes of urban culture, fashion, portraiture, and historic monographs; 8–9 JACKASS 10T H ANNIVERSARY PHOTO BOOK an MTV Press title .........................................Edited by Sean Cliver you perhaps saw us evolve from being simply an American illustrated book 10–11 TAKE IVY ................Photographs by Teruyoshi Hayashida, Text by Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, and Hajime (Paul) -

FDW 7702 RICKY POWELL Rappin with the Rickster DVD

DISC 1 (TOTAL RUNNING TIME: 1 Hour 38 Minutes) BEST OF RAPPIN’ WITH THE RICKSTER (1990-1994) CHAPTER 01 - Intro / Dr. Revolt CHAPTER 02 - Russell Simmons / Laurence Fishburne CHAPTER 03 - Run-D.M.C. CHAPTER 04 - King Adrock / Cey Adams CHAPTER 05 - K-Rob I Dondi White CHAPTER 06 - Cypress Hill / Futura 2000 CHAPTER 07 - Beastie Boys (In Studio, 1991) CHAPTER 08 - Dr. Revolt CHAPTER 09 - Beastie Boys (In Studio, 1991 - Part 2) / Max Perlich / Tone Loc CHAPTER 10 - Billy Preston / Kim Gordon & Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth) CHAPTER 11 - Sofia Coppola / Spike Jonze CHAPTER 12 - Sandra Bernhard / Outro RICKSTER BOUILLABAISSE CHAPTER 01 - Intro / First Guest Ever CHAPTER 02 - Russell Simmons / Kool Keith / Everlast (House Of Pain) / Doug E. Fresh / Lee 163 CHAPTER 03 - Bobbito Garcia CHAPTER 04 - Beastie Boys (In Studio, 1994 - Ill Communication) / Harold Hunter CHAPTER 05 - Afrika Bambaataa / Eazy E CHAPTER 06 - Beck / P-Funk Jam Session (Lollapalooza, 1994) CHAPTER 07 - Seen / Zephyr / Outro DISC 2 (TOTAL RUNNING TIME: 1 Hour 4 Minutes) RICKY POWELL’S WORLD FAMOUS SLIDE SHOW CHAPTER 01 - Sofia Coppola / Run-D.M.C. Jean-Michel Basquiat / Ahmet Ertegun CHAPTER 02 - John Lee Hooker / Laurence Fishburne / Lenny Kravitz CHAPTER 02 - Andy Warhol / Jean-Michel Basquiat Rick Rubin / Russel Simmons / LL Cool J / Eazy E CHAPTER 02 - The Dust Brothers / Joe Namath / Dondi White / Ricky Powell RAPPIN’ WITH THE RICKSTER 2010 CHAPTER 01 - Intro / Dante Ross Oh snap! Heavily bootlegged for years on VHS, Ricky Powell’s early 90s CHAPTER 02 - Stay High 149 Rappin’ With The Rickster cable access show gave insight into the world of CHAPTER 03 - DJ Eclipse CHAPTER 04 - Outro the foulmouthed, trouble-making New York City scenester.