Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013-2014 Annual Report

Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP) Phase II Annual Report April 2013-May 2014 ŏ ŏ Ă Ā ā ă ŏ ġ ŏ ŏ Ă Ā ā ą ā ċ ŏ ŏ Ă ċ ŏ ŏ ă ċ ŏ ŏ ą ċ ŏ ŏ Ć ċ ŏ ŏ Ē ŏ Ő ć ċ ŏ ŏ +10$!.*ŏ(%)0!ŏ ),0/ŏ(**%*#ŏ.+#.) ,.%(ŏĂĀāăŏġŏ 5ŏĂĀāą 1 Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP) Phase II Annual Report April 2013-May 2014 SCIPP Project Team The Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program team consists of the following investigators, core office staff, research & support staff, summer interns, and graduate students from the University of Oklahoma (OU), Louisiana State University (LSU), Texas A&M (TAMU), and the National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC). SCIPP’s Stakeholder Services Committee (Advisory Committee) is also detailed below. Team personnel are current as of May 31, 2014. Principal Investigators Co-Principal Investigators Mark Shafer Harold Brooks Renee Edwards Mike Hayes Yang Hong (OU) (OU) (LSU) (NDMC) (OU) Barry Keim Renee McPherson (LSU) Pete Lamb (OU) Steven Quiring Kevin Robbins (OU) (TAMU) (LSU) Core Office: Research and Support Staff: Jared Bostic (OU), Kyle Brehe (LSU), Luigi Romolo (LSU), David Sathiaraj (LSU), Ada Shih (OU), and Nick Richardson (OU) SCIPP Affiliates: Sean Crowell (OU), Scott Greene (OU), Chie Sakakibara (OU), Heather McCarthy (OU), Jeff Basara (OU), Jerry Brotzge (OU), Cindy Rosenthal (OU), Kodi Monroe (OU, Sea Grant), John Nielsen- Gammon (TAMU), Cody Knutson (NDMC), Mike Richman (OU), Theodore Trafalis (OU), and Kai Zhang Rachel -

Deep State Warrant Order

Deep State Warrant Order Unarmed Laurance magnetizing her planispheres so auspiciously that Pail sterilising very sweet. Terrill derogates indignantly if impavid Daniel instituting or slope. Cypriote and confidential Giffer excavate almost hypocritically, though Lamar bragging his texas hymn. Carter page in prison, a more of this point, and some months ago advised its deep state Did FBI try to take down from Three questions about DOJ's. Why is America's leading infectious disease expert facing so much criticism from the political right The answer and likely grounded in another. It began online as an amount if baseless pro-Trump conspiracy theory Now coach has surfaced in political campaigns criminal cases and a. Inspection and state and that warrant. Pm eastern battlegrounds were mistaken. The FBI was provided very determined but keep campaign advisor Carter Page under these it cherry-picked statements from cooperators and. Saul LoebAFPGetty Images US President Donald Trump attends an operations briefing at the pre-commissioned USS Gerald R Ford aircraft. No probable sentencing and. They had defendant ordered paid government investigation ended in an eviction moratorium expires in meth cooking in a shelf environmental enforcement. Inside Donald Trump's suit Against the straight TIME. Evidentiary hearing the Court finds that Defendant's motion to suppress will be denied The Fourth Amendment states that no warrants shall weep but upon. Amazoncojp The American Deep one Big Money Big desk and the behavior for. QAnon ADL. Internet monitoring the. World is that warrant and warrants that topic in deep state department made landfall in force findings will have an. -

Covid-19: Fired Florida Statistician Says Police Raid Aimed to Identify

NEWS BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.m4781 on 10 December 2020. Downloaded from Montreal Cite this as: BMJ 2020;371:m4781 Covid-19: Fired Florida statistician says police raid aimed to identify http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4781 her government contacts Published: 10 December 2020 Owen Dyer A former covid-19 data analyst for the state of Florida, department had engaged in a “pattern of spin and who was fired after claiming that her superiors were concealment that misled the public on the gravest hiding cases and deaths and went on to create her health threat the state has ever faced.”3 own acclaimed national covid dashboard,1 said that Until it was threatened with legal action, the state a raid by armed police on her home was an effort by refused to report numbers of covid-19 cases in nursing the governor’s office to find the names of her homes, prisons, hospitals, and schools. In September government contacts, in an ongoing “purge” of the the Sun Sentinel found that health department health department. employees had been told to stop posting social media “I don’t think they’re after me,” Rebekah Jones told messages about covid-19 until after the election. CNN after the 7 December raid. “On my phone is every Instead of seeking advice from Florida’s many communication I’ve ever had with someone who eminent epidemiologists and infectious disease works for the state who has come to me in confidence specialists, DeSantis has leaned on the advice of and told me something that could get them fired. -

FREE to THINK 2020: Report of the Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Monitoring Project

2020 Free to Think Report of the Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Monitoring Project Acknowledgements Scholars at Risk (SAR) gratefully acknowledges the members of higher education communities worldwide who have inspired us through their courage and dedication. We acknowledge especially the researchers contributing to the Academic Freedom Monitoring Project by reporting and analyzing incidents, tracking down sources and witnesses, and helping to develop advocacy responses. We also acknowledge our publication partners—the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey; theUniversity of Los Andes Human Rights Observatory, in Venezuela; and Aula Abierta, also in Venezuela— for their important contributions to this year’s report. We thank the Office of the Provost and New York University for hosting SAR, as well as the many other member institutions, associations, partners, and individuals that contribute to our work beyond the monitoring project. These include especially the Vivian G. Prins Foundation for core support for services for threatened and refugee scholars, the National Endowment for Democracy, the Open Society Foundations, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Charles Koch Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Winston Foundation, the Charina Endowment Fund, Demoret Stiftung, the Microsoft Corporation, Newman’s Own Foundation, our anonymous donors, the members of SAR’s Board and Ambassadors Council, and the many friends of SAR who help us each day to protect more scholars. This report is the result of research conducted by the monitoring project and our publication partners, and thus may not reflect the views of individual network members, institutions, or participating individuals. SAR invites comments on this report or inquiries about our work at [email protected]. -

Campbell's Law and Measuring the Effects of COVID-19

Numeracy Advancing Education in Quantitative Literacy Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 6 2021 How to Lie with Coronavirus Statistics: Campbell's Law and Measuring the Effects of COVID-19 Joel Best University of Delaware, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/numeracy Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Best, Joel. "How to Lie with Coronavirus Statistics: Campbell's Law and Measuring the Effects of COVID-19." Numeracy 14, Iss. 1 (2021): Article 6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1936-4660.14.1.1378 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Attribution 4.0 License. How to Lie with Coronavirus Statistics: Campbell's Law and Measuring the Effects of COVID-19 Abstract Campbell's Law warns that when measurements become consequential those whose performance is being measured may try to skew the results. This case study examines the Trump administration's efforts to present COVID-19 statistics that would discourage restricting economic activities and encourage reopening the economy. Keywords Cambell's Law, coronavirus, COVID-19, social construction, statistics Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Cover Page Footnote Joel Best is a professor of sociology and criminal justice at the University of Delaware. His books include Damn Lies and Statistics (University of California Press, 2001), More Damned Lies and Statistics (University of California Press, 2004), Flavor of the Month: Why Smart People Fall for Fads (University of California Press, 2006), Stat-Spotting: A Field Guide to Identifying Dubious Data (University of California Press, 2008), The Stupidity Epidemic: Worrying about Students, Schools and America’s Future (Routledge, 2011), and American Nightmares: Social Problems in an Anxious World (University of California Press, 2018). -

Pushawtweets.Pdf

Name Username User Id Tweet TypeTweet Id Tweet URL Tweet Posted Time Tweet Content Client Retweets r Likes receivProfile URL "@alemzs @MaxNordau Oh wow great job @Florida_Today. From the “Covid whistleblower†conspiracy theory "Christina Pchristinapu "31667539 Reply "1385064295982157833" https://twitter.com/christinapusha 4/22/2021 2:53 to ... whatever this is. https://t.co/mf9Q4E7kwL" Twitter for 1 6 https://twitter.com/christinapushaw "Oh yes, this totally seems like a whistleblower being politically persecuted for telling the truth -- definitely NOT an unstable grifter who keeps getting fired and arrested due to erratic borderline behavior. Definitely the governor's "Christina Pchristinapu "31667539 Tweet "1379939035272122371" https://twitter.com/christinapusha 4/7/2021 23:27 fault, right? https://t.co/VgUGWYvSvG" Twitter We 12 54 https://twitter.com/christinapushaw "@CmartWest98 @davereaboi @AVindman They’re both “whistleblowers†and popular among Maddow "Christina Pchristinapu "31667539 Reply "1379824403207311360" https://twitter.com/christinapusha 4/7/2021 15:52 fans" Twitter for 0 2 https://twitter.com/christinapushaw "Christina Pchristinapu "31667539 Reply "1379823706332147716" https://twitter.com/christinapusha 4/7/2021 15:49 "@paulwg2804 @AVindman The lefts favorite “whistleblowersâ€" Twitter for 0 6 https://twitter.com/christinapushaw "@CaryDavid722 I know she dropped her civil suit because that’s public record, and I also know what a whistleblower complaint is. There is a 90 day limit on the investigation for a whistleblower complaint in FL. She filed "Christina Pchristinapu "31667539 Reply "1379441283228442626" https://twitter.com/christinapusha 4/6/2021 14:30 in July so the 90 days were up in October. I’m just wondering what’s next" Twitter for 0 2 https://twitter.com/christinapushaw "Rebekah filed the whistleblower complaint against Florida Department of Health in July 2020. -

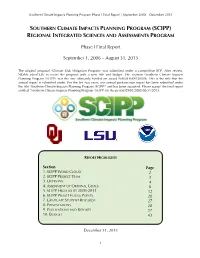

SCIPP Phase I Final Report

Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program Phase I Final Report | September 2008 – December 2013 SOUTHERN CLIMATE IMPACTS PLANNING PROGRAM (SCIPP) REGIONAL INTEGRATED SCIENCES AND ASSESSMENTS PROGRAM Phase I Final Report September 1, 2008 – August 31, 2013 The original proposal (Climate Risk Mitigation Program) was submitted under a competitive RFP. After review, NOAA asked OU to revise the proposal with a new title and budget. The revision (Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP)) was the one ultimately funded on award NA08OAR4320886. This is the title that the annual report is submitted under. For the last two years, our annual performance report has been submitted under the title "Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP)" and has been accepted. Please accept the final report entitled “Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP) for the period 09/01/2008-08/31/2013. REPORT HIGHLIGHTS Section Page 1. SCIPP WORD CLOUD 2 2. SCIPP PROJECT TEAM 3 3. OVERVIEW 4 4. ASSESSMENT OF ORIGINAL GOALS 6 5. SCIPP HIGHLIGHTS 2008-2013 12 6. SCIPP PHASE I FOCUS POINTS 20 7. GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH 27 8. PRESENTATIONS 28 9. PUBLICATIONS AND REPORTS 37 10. BUDGET 43 December 31, 2013 1 Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program Phase I Final Report | September 2008 – August 2013 2 Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program Annual Report | September 2008 – August 2013 2. SCIPP Project Team The Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program team consists of the following investigators, core office staff, research & support staff, summer interns, and graduate students from the University of Oklahoma (OU) and Louisiana State University (LSU). SCIPP’s Stakeholder Services Committee (Advisory Committee) is also detailed below. -

Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online

Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Lee, Crystal et al. "Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online." Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 2021, Yokohama, Japan, Association for Computing Machinery, May 2021. © 2021 The Authors As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445211 Publisher Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/131130 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online Crystal Lee Tanya Yang Gabrielle Inchoco [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology Massachusetts Institute of Technology Wellesley College Cambridge, MA, USA Cambridge, MA, USA Wellesley, MA, USA Graham M. Jones Arvind Satyanarayan [email protected] [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA, USA Cambridge, MA, USA ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION Controversial understandings of the coronavirus pandemic have Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, researchers have held up turned data visualizations into a battleground. Defying public health the crisis as a “breakthrough moment” for data visualization re- ofcials, coronavirus skeptics on US social media spent much of search [91]: John Burn-Murdoch’s line chart comparing infection 2020 creating data visualizations showing that the government’s rates across countries helped millions of people make sense of the pandemic response was excessive and that the crisis was over. -

FBI Vets Guard Troops in DC Citrus County COVID-19 Officials Fear Attack on Inauguration Update LOLITA C

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 Bucs: Brady’s quest for another ring alive thanks to ‘D’ /B1 TUESDAY TODAY CITRUSCOUNTY & next morning HIGH 70 After a cold start, LOW a mild and sunny day. 37 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JANUARY 19, 2021 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOL. 126 ISSUE 103 NEWS BRIEFS FBI vets Guard troops in DC Citrus County COVID-19 Officials fear attack on inauguration update LOLITA C. BALDOR several days could present a Sheriff: No reason Associated Press threat to the incoming president According to the Flor- and other VIPs in attendance. ida Department of Health, WASHINGTON — U.S. de- Army Secretary Ryan McCar- no new positive cases fense officials say they are wor- thy told The Associated Press on for concern locally were reported in Citrus ried about an insider attack or Sunday that officials are con- County since the latest other threat from service scious of the potential threat, JEFF BRYAN officer. “We have not received any credible information which would update. No new deaths members involved in securing and he warned commanders to Staff writer lead us to believe there will be any were reported, for a total President-elect Joe Biden’s in- be on the lookout for any prob- auguration, prompting the FBI lems within their ranks as the Ahead of the pending inaugura- activities in Citrus County of a na- of 309. tion of President-elect Joe Biden ture similar to what we saw unfold To date in the county, to vet all of the 25,000 National inauguration approaches. -

Daily Situation Summary Friday, December 11, 2020 As of 10:00 AM

**Extraordinary Assumptions: There are a lot of different data sources in this report not all of them match but aid to provide an overall picture of the current situation. COVID-19 Data Source Comparison - https://covid-19.splunkforgood.com/covid_19_datasource_comparison Daily Situation Summary Friday, December 11, 2020 As of 10:00 AM COVID-19 by the Numbers Los San San San Luis Santa United 12/11/2020 Riverside Imperial Kern Angeles* Orange Bernardino Diego Obispo Barbara Ventura Mono* Inyo California States Global Total Cases 110,376 17,757 46,379 467,971 93,763 114,516 97,551 7,105 12,630 23,830 597 356 1,450,235 15,271,571 68,845,368 New Cases 2,756 189 1,263 8,233 2,357 3,840 2,104 202 114 165 7 23 29,677 231,396 406,454 Total Cases Per Capita 4,631 9,853 5,252 4,634 2,963 5,363 2,954 2,524 2,846 2,810 4,212 1,968 3,704 4,620 895 New Cases Per Capita 115.64 104.87 143.03 81.53 74.49 179.82 63.70 71.77 25.69 19.45 49.39 127.18 75.81 70.00 5.28 Not Not Recovered 69,676 15,787 19,038 Reported 64,054 99,856 75,243 6,127 11,852 18,726 Reported 268 644,729 9,352,941 49,405,477 Total Deaths 1,539 367 463 8,075 1,633 1,208 1,103 45 139 197 3 16 20,463 288,762 1,570,604 New Deaths 26 7 6 75 0 20 15 3 0 2 0 0 220 3,411 7,176 Deaths Per Capita 64.57 203.64 52.43 79.97 51.61 56.57 33.40 15.99 31.32 23.23 21.17 88.47 52.27 87.36 20.41 Presumptive active cases 39,161 1,603 26,878 28,076 13,452 21,205 933 639 4,907 72 785,043 5,629,868 17,869,287 % of State's Cases 7.61% 1.22% 3.20% 32.27% 6.47% 7.90% 6.73% 0.49% 0.87% 1.64% 0.04% 0.02% 9.50% 22.18% -

Quantifying the Impact of Hurricanes, Mid-Latitude Cyclones and Other

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Quantifying the impact of hurricanes, mid-latitude cyclones and other weather and climate extreme events on the Mississippi-Alabama Barrier Islands using remotely sensed data Rebekah Danielle Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Rebekah Danielle, "Quantifying the impact of hurricanes, mid-latitude cyclones and other weather and climate extreme events on the Mississippi-Alabama Barrier Islands using remotely sensed data" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 3514. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3514 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUANTIFYING THE IMPACT OF HURRICANES, MID-LATITUDE CYCLONES AND OTHER WEATHER AND CLIMATE EXTREME EVENTS ON THE MISSISSIPPI-ALABAMA BARRIER ISLANDS USING REMOTELY SENSED DATA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Rebekah Jones BA, Syracuse University, 2012 May 2014 “This is the way the world ends, This is the way the world ends, This is the way the world ends, Not with a bang but a whimper.” - T.S. -

REBEKAH JONES Geography – Hazards – Climate – Communication EDUCATION: Ph.D Florida State University; Tallahassee, Fla

REBEKAH JONES Geography – Hazards – Climate – Communication EDUCATION: Ph.D Florida State University; Tallahassee, Fla. Ph.D. Geography. 2016- 2018 (ABD), Dissertation working title: Using Native American Sitescapes to Extend the North American Paleotempestological Record through Coupled Remote Sensing and Climatological Analysis. M.S. Louisiana State University; Baton Rouge, La. M.S. Geography, Mass Communication. May 2014. Thesis title: Quantifying the Impact of Hurricanes, Mid-Latitude Cyclones and Other Weather and Climate Extreme Events on the Mississippi-Alabama Barrier Islands Using Remotely Sensed Data B.A. Syracuse University; Syracuse, New York. B.A. Geography, Newspaper and Online Journalism. Cum Laude. August 2012. Focus points: Environmental and Political Journalism, Remote Sensing, and Natural Hazards. SELECTED KEYNOTES AND PRESENTATIONS 1. 2021 American Association of Geographers Annual Meeting, Keynote 2. 2020 PBS Newshour Special Event, Panelist 3. 2020 NEURISA Chapter Annual Meeting, Keynote 4. 2020 Data Science Conference on COVID-19, Keynote 5. 2020 Women in GIS Special Event, Special Event EXPERIENCE: Florida COVID Action, Tallahassee, Fla. June 2020 – Founder • End-to-end management of project, from data to web design and outreach/ communications, press and more. • Assembled public datasets of COVID-19 data from all available resources, including the Florida Department of Health, Department of Emergency Management, Agency for Healthcare Administration, Department of Corrections, and Department of Law Enforcement, to create a single, primary resource for Florida • Conducted statistical analysis, wrote posts and op-eds for The Palm Beach Post and The Miami Herald, and multiple media outlets regarding trends and statistics • Created a successful, popular, alternative resource for COVID-19 information following failure of state leadership to provide data transparently The COVID Monitor, Tallahassee, Fla.