A Review of China's Animal Protection Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forum of Animal Law Studies) 2019, Vol

dA.Derecho Animal (Forum of Animal Law Studies) 2019, vol. 10/1 35-58 Animal Law in South Africa: “Until the lions have their own lawyers, the 1 law will continue to protect the hunter” Amy P. Wilson Attorney. LL.M Animal Law Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, USA Director and Co-founder Animal Law Reform South Africa Received: December 2018 Accepted: January 2019 Recommended citation. WILSON A.P., Animal Law in South Africa: “Until the lions have their own lawyers, the law will continue to protect the hunter”dA. Derecho Animal (Forum of Animal Law Studies) 10/1 (2019) - DOI https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/da.399 Abstract Despite the importance of animals to South Africa, animal law is not yet recognized a separate distinct area of law. In an attempt to rectify this, the article provides a high level introduction to this highly complex field. By providing background and context into historical and current injustices regarding humans and animals, it alleges that the current legal system has failed to provide adequate protection to either group. By analyzing the existing regulatory framework and case law, it lays out the realities of obtaining better protection for animals in law. It then argues why it is particularly critical for the country to consider animal interests both individually and collectively with human interests by providing examples of how these interests intersect in practice. It suggests an approach for future protection efforts and concludes by providing some opportunities going forward for animal law reform in South Africa. Keywords: Animal law; South Africa; animals; animal protection; law; human rights. -

Animals Asia Review 2013 15 Years of Changing Lives

Animals Asia Review 2013 15 years of changing lives www.animalsasia.org About Animals Asia The Animals Asia team has been rescuing bears since 1994. Animals Asia is the only organisation with sanctuaries in China and Vietnam dedicated to rehabilitating bears rescued from the bile trade. Our founder and CEO, Jill Robinson MBE is widely recognised as the world’s leading expert on the cruel bear bile industry, having campaigned against it since 1993. Our other two programmes, Cat and Dog Welfare and Zoos and Safari Parks, are based in China, where we work with local authorities and communities to bring about long-lasting change. Our mission Animals Asia is devoted to the needs of wild and domesticated species in Asia. We are working to end cruelty and restore respect for animals across Asia. Our vision Change for all animals, inspired by empathy for the few. Our animal ambassadors embody the ideal that empathy for one animal can evolve into empathy for an entire species and ultimately for all species. Board of Directors John Anneliese Jonathon Charles Melanie Kirvil Warham Smillie ‘Joe’ Kong Pong Skinnarland Chairman Vice-Chairman Hancock Government Philanthropist Trustee of an Pilot, flight Former Animals Senior executive consultant with more animal foundation simulator Asia Education in the finance on animal than 15 years, and longtime instructor and Director and long- industry and long- management and involvement with Animals Asia founding member term supporter. term Animals Asia animal welfare Animals Asia. adviser and of Animals Asia. China supporter. adviser. Hong Kong supporter. Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong USA 2 Animals Asia Review 2013 LETTER From JILL Dear friends, From kindergarten presentations to government consultations, from traumatic live-animal market investigations to presentations and advertising campaigns, Animals Asia’s strategy is working. -

Wild at Heart the Cruelty of the Exotic Pet Trade Left: an African Grey Parrot with a Behavioural Feather-Plucking Problem, a Result of Suffering in Captivity

Wild at heart The cruelty of the exotic pet trade Left: An African grey parrot with a behavioural feather-plucking problem, a result of suffering in captivity. Wildlife. Not Pets. The exotic pet trade is one of the biggest threats to millions of Everyone, from our supporters and pet-owners to the wider wild animals. World Animal Protection’s new Wildlife. Not public has an important role to play in protecting millions of Pets campaign aims to disrupt this industry and to protect wild wild animals from terrible suffering. We will work together animals from being poached from the wild and bred into to uncover and build awareness of this suffering, and take cruel captivity, just to become someone’s pet. action to stop the cruelty. This campaign builds on sustained successful campaigning Companies, governments and international trade to protect wild animals from the cruel wildlife tourism industry. organisations involved in the wildlife pet trade, whether Since 2015, over 1.6 million people around the globe have wittingly or not, all have a crucial role to play. They can cut taken action to move the travel industry. TripAdvisor and out illegal wildlife crimes, and they can do more to protect other online travel platforms have committed to stop profiting wild animals from this cruellest of trades. from wildlife cruelty. Over 200 travel companies worldwide have pledged to become elephant and wildlife-friendly. Now is the time to turn the tide on the exotic pet trade and keep wild animals in the wild, where they belong. Wildlife. Not Pets focuses a global spotlight on the booming global trade in wild animals kept as pets at home, also known as ‘exotic pets’. -

Wildlife Farms, Stigma and Harm

animals Article Wildlife Farms, Stigma and Harm Jessica Bell Rizzolo Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA; [email protected] Received: 25 August 2020; Accepted: 28 September 2020; Published: 1 October 2020 Simple Summary: Wildlife farming is a practice where wild animals are legally bred for consumption in a manner similar to agricultural animals. This is a controversial conservation practice that also has implications for animal welfare and human livelihoods. However, most work on wildlife farming has focused solely on conservation or animal welfare rather than considering all of these ethical factors simultaneously. This paper uses interview data with academics to analyze (a) the harms and benefits of wildlife farms and (b) how wildlife farms are labeled detrimental (stigmatized) or acceptable. Results indicate that consideration of the harms and benefits of wildlife farms incorporate conservation, animal welfare, scale disparities between sustenance and commercial farms, consumer preferences, species differences, the dynamics of demand for wildlife products, and governance. Whether wildlife farms are stigmatized or accepted is influenced by different social constructions of the term “wildlife farm”, if there is a stigma around use of a species, a form of production, or the perceived quality of a wildlife product, cultural differences, consumer preferences, geopolitical factors, and demand reduction efforts. This paper discusses how the ethics of wildlife farms are constructed and how shifts in context can alter the ethical repercussions of wildlife farms. Abstract: Wildlife farming, the commercial breeding and legal sale of non-domesticated species, is an increasingly prevalent, persistently controversial, and understudied conservation practice. -

The Impact of Information on Attitudes Toward Sustainable Wildlife Utilization and Management: a Survey of the Chinese Public

animals Article The Impact of Information on Attitudes toward Sustainable Wildlife Utilization and Management: A Survey of the Chinese Public Zhifan Song 1,† , Qiang Wang 2,†, Zhen Miao 1 , Kirsten Conrad 3, Wei Zhang 1,*, Xuehong Zhou 1,* and Douglas C. MacMillan 4 1 College of Wildlife and Protected Area, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China; [email protected] (Z.S.); [email protected] (Z.M.) 2 Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun 130102, China; [email protected] 3 International Association for Wildlife, Gungahlin, Canberra, ACT 2912, Australia; [email protected] 4 Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7NR, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.Z.); [email protected] (X.Z.) † Equal contributions. Simple Summary: The widespread dissemination of information related to wildlife utilization in new online media and traditional media undoubtedly impacts societal conservation concepts and attitudes, thus triggering public discussions on the relationship between conservation and utilization. In this study, questionnaires were distributed in seven major geographic regions of Chinese mainland Citation: Song, Z.; Wang, Q.; Miao, to investigate the public’s awareness and agreement with information related to the utilization of Z.; Conrad, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; wildlife in order to measure the impact of information on various issues relating wildlife conservation MacMillan, D.C. The Impact of and utilization. The Chinese public had the greatest awareness and agreement with information Information on Attitudes toward that prevents unsustainable and illegal utilization, and the least awareness and agreement with Sustainable Wildlife Utilization and information that promotes unsustainable utilization. -

Animal Welfare Consciousness of Chinese College Students: Findings and Analysis

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 3-2005 Animal Welfare Consciousness of Chinese College Students: Findings and Analysis Zu Shuxian Anhui Medical University Peter J. Li University of Houston-Downtown Pei-Feng Su Independent Animal Welfare Consultant Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/socatani Recommended Citation Shuxian, Z., Li, P. J., & Su, P. F. (2005). Animal welfare consciousness of Chinese college students: findings and analysis. China Information, 19(1), 67-95. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Welfare Consciousness of Chinese College Students: Findings and Analysis Zu Shuxian1, Peter J. Li2, and Pei-Feng Su3 1 Anhui Medical University 2 University of Houston-Downtown 3 Independent Animal Welfare Consultant KEYWORDS college students, cultural change, animal welfare consciousness ABSTRACT The moral character of China’s single-child generation has been studied by Chinese researchers since the early 1990s. Recent acts of animal cruelty by college students turned this subject of academic inquiry into a topic of public debate. This study joins the inquiry by asking if the perceived unique traits of the single-child generation, i.e. self- centeredness, lack of compassion, and indifference to the feelings of others, are discernible in their attitudes toward animals. Specifically, the study investigates whether the college students are in favor of better treatment of animals, objects of unprecedented exploitation on the Chinese mainland. With the help of two surveys conducted in selected Chinese universities, this study concludes that the college students, a majority of whom belong to the single-child generation, are not morally compromised. -

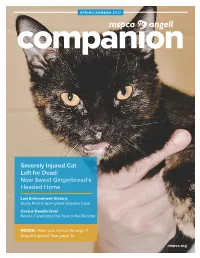

Spring/Summer 2017

SPRING/SUMMER 2017 Severely Injured Cat Left for Dead: Now Sweet Gingerbread’s Headed Home Law Enforcement Victory: Guilty Plea in Springfield Hoarder Case Cock-a-Doodle-Doo! Nevins Celebrates the Year of the Rooster INSIDE: Have you visited George T. Angell’s grave? See page 12 mspca.org Table of Contents Did You Know... Cover Story: Severely Injured Cat Left for Dead .........1 ...that the MSPCA–Angell is a Angell Animal Medical Center ............................................2 stand-alone, private, nonprofit organization? We are not Advocacy ...................................................................................3 operated by any national humane Cape Cod Adoption Center .................................................4 organization. Donations you Nevins Farm ..............................................................................5 make to “national” humane PR Corner, Events Update ....................................................6 organizations do not funnel down Boston Adoption Center .......................................................7 to the animals we serve Law Enforcement .....................................................................8 in Massachusetts. The Angell Surgeon Honored .....................................................9 MSPCA–Angell relies Donor Spotlight ......................................................................10 solely on the support of Archives Corner ..................................................................... 12 people like you who care deeply about animals. -

Under What Circumstances Can Wildlife Farming Benefit Species

Global Ecology and Conservation 6 (2016) 286–298 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Review paper Under what circumstances can wildlife farming benefit species conservation? Laura Tensen ∗ Molecular Zoology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa h i g h l i g h t s • Farmed wildlife products should be consider equal in quality, taste, and status. • The demand for wildlife products cannot increase due to the legalized market. • Wildlife farming should be more cost-efficient than poaching. • Wildlife farms should not depend on wild populations for restocking. • Laundering of illegal wildlife products into the commercial trade should be absent. article info a b s t r a c t Article history: Wild animals and their derivatives are traded worldwide. Consequent poaching has been a Received 8 December 2015 main threat to species conservation. As current interventions and law enforcement cannot Received in revised form 22 March 2016 circumvent the resulting extinction of species, an alternative approach must be considered. Accepted 22 March 2016 It has been suggested that commercial breeding can keep the pressure off wild populations, referred to as wildlife farming. During this review, it is argued that wildlife farming can benefit species conservation only if the following criteria are met: (i) the legal products Keywords: will form a substitute, and consumers show no preference for wild-caught animals; (ii) Wildlife trade Wildlife farming a substantial part of the demand is met, and the demand does not increase due to the Commercial breeding legalized market; (iii) the legal products will be more cost-efficient, in order to combat Rhino horn the black market prices; (iv) wildlife farming does not rely on wild populations for re- Bear bile stocking; (v) laundering of illegal products into the commercial trade is absent. -

Animals Asia Foundation Limited Financial Statements

Animals Asia Foundation Limited Financial Statements & Independent Auditor’s Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS INDEPENDENT AUDITOR'S REPORT ...........................................................................3 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS .............................................................................................5 Statement of Financial Position ...........................................................................................5 Statement of Activities and Changes in Net Assets .............................................................6 Statement of Functional Expenses .......................................................................................7 Statement of Cash Flows .....................................................................................................8 Notes to Financial Statements ..............................................................................................9 Independent Auditor's Report To the Board of Directors Animals Asia Foundation Limited Los Angeles, California We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Animals Asia Foundation Limited (a nonprofit organization), which comprise the statement of financial position as of December 31, 2019, the related statements of activities and changes in net assets, functional expenses, and cash flows for the year then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and -

Animals Asia Review 2014 the Year of Our Supporters

Animals Asia Review 2014 The Year of our Supporters www.animalsasia.org Our mission Animals Asia is devoted to the needs of wild and domesticated species in Asia. We are working to end cruelty and restore respect for animals across Asia. Our vision Change for all animals, inspired by empathy for the few. Our animal ambassadors embody the ideal that empathy for one animal can evolve into empathy for an entire species and ultimately for all species. Message from our board Our ambitious project to turn a Chinese bile farm into a sanctuary for the 130 bears trapped inside made 2014 our most challenging year to date. We needed your support like never before and when we asked for it, you gave it to us. Without you, we could not have achieved our aims, not only for the animals, but also for the future of our organisation. Thank you all so much. Board of Directors John Warham Anneleise Smillie Chairman Vice-Chairman Pilot, flight simulator Former Animals Asia instructor and founding Education Director and member of Animals Asia. long-term supporter. Hong Kong China Jonathon ‘Joe’ Melanie Pong Kirvil Skinnarland Hancock Philanthropist with more Trustee of an animal Senior executive in the than 15 years’ involvement foundation and longtime finance industry and long- with Animals Asia. Animals Asia adviser and term Animals Asia supporter. Hong Kong supporter. Hong Kong USA Cover boy Oliver lived at our Chengdu sanctuary for four years until his death in 2014. Oliver was rescued from a farm in Shandong province after surviving 30 years in a cage. -

Animals Asia Foundation Report

Animals Asia Foundation Report Compromised health and welfare of bears in China’s bear bile farming industry, with special reference to the free-dripping bile extraction technique March 2007 Kati Loeffler, DVM, PhD Email: katiloeffl[email protected] Jill Robinson, MBE [email protected] Gail Cochrane, BVMS, MRCVS [email protected] Animals Asia Foundation, GPO Box 374, General Post Office, Hong Kong www.animalsasia.org ABSTRACT The practice of farming bears for bile extraction is legal in China and involves an estimated 7,000 bears, primarily Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus). This document describes bear farming in China, with an emphasis on the health and disease of the bears and the long-term effects of bile extraction. Gross pathology of the gall bladder and surrounding abdominal tissues is described. The data presented here establishes the inhumanity of bear bile farming on the grounds that it severely and unavoidably compromises the physical and psychological health of the bears and that it violates every code of ethical conduct regarding the treatment of animals. All considerations of ethics, wildlife conservation, veterinary medicine and, ultimately, economics, lead to the conclusion that bear bile farming is an unacceptable practice and must end. INTRODUCTION Bears farmed for extraction of their bile are generally confined to cages the size of their bodies; are deprived of food, water and movement; suffer chronic pain, illness and abuse; and live with holes in their abdomens, from which the “liquid gold” of a multi-million dollar industry flows. Bear bile farming is legal in China and involves an estimated 7,000 bears, primarily Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus). -

Pills, Powders, Vials and Flakes: the Bear Bile Trade in Asia (PDF, 1.8

Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2011 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the author expressed in this SXEOLFDWLRQGRQRWQHFHVVDULO\UHÀHFWWKRVH of the TRAFFIC network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Foley, K.E., Stengel, C.J. and Shepherd, C.R. (2011). Pills, Powders, Vials and Flakes: the bear bile trade in Asia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. ISBN 978-983-3393-33-6 Cover: Composite image created by Olivier S. Caillabet Photos from top to bottom: 1) Bear cub observed on farm in Hanoi, Viet Nam 2) Vials of bear bile observed on farm in Viet Nam 3) Alleged bear gall bladder observed for sale in Singapore 4) Pills claimed to contain bear bile for sale in Malaysia Photograph credits: M. Silverberg/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia (1,2) C. Yeong/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia (3,4) Pills, Powders, Vials and Flakes: the bear bile trade in Asia Kaitlyn-Elizabeth Foley Carrie J.