Bruxelles, 2014 Art and Literature Scientific and Analytical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tokyo Takarazuka Theater(TOKYO) Jan.8-Feb.21 2021

Tokyo Takarazuka Theater(TOKYO) Jan.8-Feb.21 2021 Mitsui-Sumitomo Card Musical "ANASTASIA THE MUSICAL" Book:TERRENCE McNALLY Music:STEPHEN FLAHERTY Lyrics:LYNN AHRENS Inspired by the Twentieth Century Fox Motion Picture by special arrangement with Buena Vista Theatrical From the play by Marcelle Maurette as adapted by Guy Bolton Adaptation and direction by Daichi Inaba Exclusive Representation in Japan By BROADWAY ASIA COMPANY, LLC www.broadwayasia.com Commissioned by Dmitry Bogachev Original Broadway Producers: Stage Entertainment, Bill Taylor, Tom Kirdahy, Hunter Arnold On sale from: December 27, 2020, at 10:00 AM(JST) - Price SS Seat : 12,500 / S Seat : 9,500 / A Seat : 5,500 / B Seat : 3,500 Unit: Japanese Yen (tax included) Story --- "ANASTASIA THE MUSICAL" The story begins in the early 20th century in St. Petersburg, Russia. One winter night, Anastasia, the youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, receives a music box from her beloved grandmother, the Dowager Empress Maria, with the words "Think of me when you play it." After then, the Dowager Empress moves to Paris. Years later, Anastasia has grown into a beautiful 17-year-old princess. However, the Romanovs are attacked by the Bolsheviks during a ball at the palace. The execution of the royal family brings an end to the glorious Romanov dynasty. Ten years have passed since the Russian Revolution. While St. Petersburg is still in turmoil, there is a rumor going around that one Romanov daughter Anastasia may have survived. Dmitry, a con man who has committed petty crimes to survive in the chaotic times, hears that the Dowager Empress is offering a huge reward for finding Anastasia. -

Harpercollins Canada, Limited, 1998 Anastasia Meets Rasputin Marco Pavia 1998 9780061070860 12 Pages

HarperCollins Canada, Limited, 1998 Anastasia Meets Rasputin Marco Pavia 1998 9780061070860 12 pages Anastasia Meets Rasputin Anastasia My First Jumbo Book of Letters Introducing Anastasia and Friends Anastasia Goes to a Party P.J. Funnybunny's Bag of Tricks Big Bear, Little Bear Pooka Visits Paris anastasia meets rasputin. crowfeathers , Published on Feb 19, 2017. 4,754 views. Anastasia - Once upon a December (Eu Portuguese). Disney em pt-pt. Anastasia Trailer 1997. AnimatedMoviesC. Anastasia - The Reunion English (BluRay HD). Anastasia Romanov. Bartok the Magnificent. YamiBakura. Arcadia Praline. Anastasia - Dimitri meets Anya fandub collab w/ alanb2013. Snowlette VA. Il mio inizio sei tu - Anastasia. Llampross. Anastasia - Once Upon A December. Abbie Rooney. Anastasia fight rasputin Anastasia tries kill rasputin Anastasia kill rasputin. "You think you can banish the great Rasputin?" Anastasia fight rasputin. Anastasia tries kill rasputin. Anastasia kill rasputin. Add a photo to this gallery. Retrieved from "http://foxsanastasia.wikia.com/wiki/Rasputin? oldid=6877". Categories: Characters. Anastasia Meets Rasputin by Marco Pavia, Fox Animation 368 x 400 jpeg 28 КБ. www.pinterest.com. gingerbreadlily: fuckyeahnondisney: Anastasia: Rasputin 600 x 315 jpeg 25 КБ. www.youtube.com. Anastasia 1997-Anastasia vs Rasputin part 1 - YouTube. 1280 x 720 jpeg 65 КБ. yurikoschneide.deviantart.com. Anastasia by YurikoSchneide on DeviantArt. 900 x 1148 png 1043 КБ. tardypodcast.com. Tardy to the Party episode 27: Anastasia ⓠTardy to the 1249 x 801 png 474 КБ. Disney Movie Walt Disney Movie Anastasia Anastasia Meets Rasputin Anastasia and Rasputin Cartoon Disney Anastasia Rasputin Young Rasputin Grigori Rasputin 996 x 575 png 382kB. -

Mercurian Vol. 3, No

The Mercurian A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 3, Number 1 Editor: Adam Versényi The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit”. The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue. -

Farmington Civic Center & Lions Wilderness Amphitheater

Farmington Civic Center FARMINGTON CIVIC CENTER 200 W Arrington • Farmington, NM 87401 www.fmtn.org/CivicCenter • (505) 599-1148 @FarmingtonCivicCenterNM The Farmington Civic Center is newly reopened from the expansion renovation. It now feature a larger ballroom and more breakout space for meetings within the multi-utilization facility, which serves as a convention and conference site, as well as a performing and visual arts center. The Civic Center business office has an on-site Box Office, as well as friendly staff to help you plan your event. Convention and business meeting rooms are equipped with audio visual equipment. BUSINESS OFFICE RENTALS HOURS OF OPERATION Call us to plan your next special event, conference or Monday - Friday • 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM show. HOLIDAY CLOSURES Facility is still available for rental on these days. January 1 • CLOSED for New Year’s Day February 17 • CLOSED for President’s Day April 10 • CLOSED for Good Friday LIONS WILDERNESS PARK AMPHITHEATER AND EVENT VENUE 5800 College Blvd • Farmington, NM 87402 • www.fmtn.org/870/Lions-Wilderness-Amphitheater (505) 599-1148 Lions Wilderness Park Amphitheater is home to the Sandstone Productions outdoor summer theater productions and also a great rental event venue. With a commercial kitchen, dining area, restrooms, and outdoor stage/theater area, it is the perfect place to host your special outdoor event. Rentals and events are managed through the Farmington Civic Center. Give us a call to plan your event today! 30 www.fmtn.org/PRCA Farmington Civic Center SHOWS GOD HELP US! Fee: $8-$18 Tickets: (505) 599-1148 • www.fmtn.org/CivicCenter Left vs. -

Education & Resource Guide

Education & Resource Guide Journey to the past THE NEW BROADWAY MUSICAL Journey to the past THE NEW BROADWAY MUSICAL ABOUT THE MUSICAL SECTION • Synopsis 3 1 • Meet the Characters 4 THE CREATIVE PROCESS • About the Creators 5 • Activity: Lyric Writing 7 • A Backstage Look: SECTION • The Life of a Costume 9 2 • Activity: Costume Creation 14 • The Opera Drop 15 THE ROMANOVS • The Romanov Family Tree 16 • The Romanov Family 17 • Grand Palace Balls 19 • Activity: Choreograph the Ball 20 SECTION • Activity: Create Your Own Family Tree 21 3 • Activity: Adapting a Legend 22 • Activity: Home Memory Collage 23 ABOUT RUSSIA • Russsia and World War I 24 • The Russian Revolution of 1917 25 SECTION • Russian Protests – February 1917 26 • Activity: Gleb Character Analysis 28 4 • Activity: Missing Scene 29 30 • Activity: Social Status Walk 1920S CULTURE 31 SECTION • Cultural Figures in the 1920s 34 5 • Activity: A Parisian Salon ANASTASIABROADWAY.COM 2 Section 1: About the Musical Synopsis NICOLE SCIMECA AND MARY BETH PEIL, ANASTASIA, Hartford Stage SAINT When the Dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna Romanov gives her beloved granddaughter Anastasia a music box, she has no idea it is the last time she will see PETERSBURG, her. As the musical ANASTASIA begins, Russia is on the verge of revolution. Time jumps from 1907 to 1927, and Anastasia’s family, the imperial Romanovs, fall victim to the tide of history. When the Dowager Empress receives the news that they have 1907 been put to death, she believes she has lost her entire family. Russia is now frmly under the Bolshevik Communists’ rule, but the winters are still SAINT cold, the people are still hungry, and rumors have begun to surface that one Romanov PETERSBURG, daughter might have survived. -

Écrits & Correspondances De Peintres

ÉCRITS & CORRESPONDANCES DE PEINTRES LUNDI 1ER AVRIL 2019 BEAUX-ARTS 1 2 ÉCRITS & CORRESPONDANCES DE PEINTRES DE BELLMER À VUILLARD CATALOGUE N°15 De Bellmer à Vuillard, selon l’ordre alphabétique, de Delacroix à Lucien Freud selon la chronologie, c’est tout un monde de l’histoire artistique des deux derniers siècles qui revit à travers ce beau florilège de lettre et d’écrits de peintres. Comme une ouverture à la vente qui va suivre de tableaux et dessins, défile un bel ensemble de lettres illustrées : Degas, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Friesz, Matisse, Calder, Villon, Picabia, Léger, Magritte, Dali, Chaissac ou Cocteau ; sans oublier quelques beaux livres illustrés par Buffet, Dali, Dubuffet et Lanskoy. Dans la sphère intime ou familiale, on remarque les belles lettres de Monet au travail sur le motif à sa chère compagne puis femme Alice, celles de Pissarro à sa femme et ses enfants, celles amusantes de Toulouse-Lautrec à sa mère ou ses grand-mères, et l’extraordinaire lettre du Douanier Rousseau à la « bien-aimée ». Les fructueux échanges entre artistes revivent à travers les correspondants de Monet : Bazille, Manet, Pissarro, Morisot, Renoir, Sisley ; à travers les lettres de Gauguin à Pissarro, ou de Kandinsky à Jawlensky… Ce sont aussi des amitiés avec les écrivains : Baudelaire (Manet), Cendrars (Léger), Cocteau (Bellmer, Matisse), Joe Bousquet (Ernst), Prévert (Calder). Le rôle important du marchand est retracé, entre autres, à travers le bel échange de Durand-Ruel avec Monet, ou les correspondances adressées au galeriste newyorkais Julien Levy par Bellmer, Calder, Duchamp ou Man Ray ; on relève aussi des lettres adressées aux amateurs et collectionneurs : Delacroix à Daniel Wilson, Gauguin à Gustave Fayet, Monet à Georges de Bellio… Les peintres prennent aussi la plume, non seulement pour écrire des lettres, mais aussi rédiger des textes, des écrits de peintres. -

Anastasia Study Guide

TEACHERS’ NOTES Aimed at primary pupils, the ideas in this study guide are intended as starting points for a cross-curricular project on the film ‘Anastasia’ at Key Stages 1 and 2. Many curriculum areas are covered although the focus is on English. The activities in this study guide seek to complement and extend the pleasure the children will have derived from their visit to the cinema, whilst at the same time meeting some of the requirements of the National Curriculum and Scottish Guidelines. FILM SYNOPSIS A little girl of eight years old is torn from her grandmother’s hands and is lost by the sweeping chaos of the revolution in Russia. The Dowager Empress never gives up the search for her beloved granddaughter Anastasia. Anya has no memory of her childhood and wants to find her true identity. In doing so she battles with the evil Rasputin who has vowed to eliminate the youngest surviving member of the royal Romanov family. Rasputin does not crush the spirit of Anya who begins to build her future. Certificate: U Running time: 94 mins Directed by: Don Bluth and Gary Goldman Distributed by: Twentieth Century Fox FACT VERSUS FICTION (a) The story of the real Anastasia is filled with mystery: We know that she actually existed and that she was a Russian princess who lived with her family in a royal palace in the early years of this century. We know that in November 1917 there was a revolution in Russia when the ordinary people finally became tired of the royal Romanov family living in luxury while they themselves were poor. -

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes Paul Gauguin: Monotypes BY RICHARD S. FIELD published on the occasion of the exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art March 23 to May 13, 1973 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART Cover: Two Marquesans, c. 1902, traced monotype (no. 87) Philadelphia Museum of Art Purchased, Alice Newton Osborn Fund Frontispiece: Parau no Varna, 1894, watercolor monotype (no. 9) Collection Mr. Harold Diamond, New York Copyright 1973 by the Philadelphia Museum of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-77306 Printed in the United States of America by Lebanon Valley Offset Company Designed by Joseph Bourke Del Valle Photographic Credits Roger Chuzeville, Paris, 85, 99, 104; Cliche des Musees Nationaux, Paris, 3, 20, 65-69, 81, 89, 95, 97, 100, 101, 105, 124-128; Druet, 132; Jean Dubout, 57-59; Joseph Klima, Jr., Detroit, 26; Courtesy M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., 18; Koch, Frankfurt-am-Main, 71, 96; Joseph Marchetti, North Hills, Pa., Plate 7; Sydney W. Newbery, London, 62; Routhier, Paris, 13; B. Saltel, Toulouse, 135; Charles Seely, Dedham, 16; Soichi Sunami, New York, 137; Ron Vickers Ltd., Toronto, 39; Courtesy Wildenstein & Co., Inc., 92; A. J. Wyatt, Staff Photographer, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Frontispiece, 9, 11, 60, 87, 106-123. Contents Lenders to the Exhibition 6 Preface 7 Acknowledgments 8 Chronology 10 Introduction 12 The Monotype 13 The Watercolor Transfer Monotypes of 1894 15 The Traced Monotypes of 1899-1903 19 DOCUMENTATION 19 TECHNIQUES 21 GROUPING THE TRACED MONOTYPES 22 A. "Documents Tahiti: 1891-1892-1893" and Other Small Monotypes 24 B. Caricatures 27 C. The Ten Major Monotypes Sent to Vollard 28 D. -

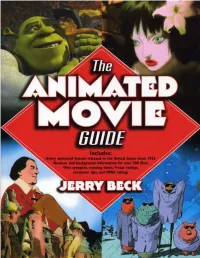

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

Del Rosellón a Mallorca. Entre El Simbolismo Y El Mediterraneísmo

BSAL #71, 2015, 227-245, ISSN: 0212-7458 DEL ROSELLÓN A MALLORCA. ENTRE EL SIMBOLISMO Y EL MEDITERRANEÍSMO Francisca Lladó Pol Universitat de les Illes Balears Resumen: Continuando con el flujo de viajeros decimonónicos procedentes del Rosellón, en las primeras décadas del siglo veinte, llegaron a Mallorca una serie de pintores-viajeros procedentes de dicha zona. Las motivaciones del viaje estarán centradas en la consideración del mediterráneo como un lugar común en el que idealmente se concreta el mito del paraíso. A través de una serie de producciones escritas y pictóricas quedará constancia de la pervivencia inequívoca de un estilo y unos postulados estéticos de gran similitud. Louis Codet, Louis Bausil y Gustave Fayet serán los artistas analizados, aun cuando se tiene constancia que no fueron los únicos en llegar a la isla. En todo caso, los artistas escogidos permiten entender el verdadero motivo del viaje que se fundamenta en una concepción supranacional del Mediterráneo y se concreta en unas opciones estéticas oscilantes entre el simbolismo y el clasicismo del Sur de Francia. Palabras clave: Mediterraneismo, Simbolismo, Clasicismo, Rosellón, Mallorca, Artistas-viajeros. Abstract: Continuing the flow of nineteenth-century travellers from Roussillon, in the early decades of the twentieth century, a number of traveller painters from the same area came to Majorca. The motivations of the trip focus on taking the Mediterranean as a common place where ideally the myth of paradise is specified. A series of pictorial and written productions will record the survival of a style and aesthetic postulates of great similarity. Louis Codet, Louis Bausil and Gustave Fayet will be the analyzed artists, even when there is evidence that they were not the only ones to reach the island. -

Artistes Collectionneurs. Ce Que Révèlent Les Archives

§archivio è potere Artistes collectionneurs. Ce que révèlent les archives de Gwendoline Corthier-Hardoin Introduction L’artiste et le collectionneur forment généralement deux maillons d’une même chaîne de circulation de l’œuvre : l’un la produisant, l’autre l’achetant. Pourtant, de nombreux artistes ont été des collectionneurs actifs. Peu de travaux, parmi la multitude de ceux qui traitent des collectionneurs (Haskell, 1986 ; Pomian, 1987 ; Cabanne, 2003 ; Moureau, 2010, 2016), ont pris comme objet d’analyse les artistes collectionneurs. Les quelques ouvrages qui prennent en compte l’artiste et sa pratique de la collection choisissent le plus souvent de les présenter sur le mode monographique. Ce type de recherches ne donne pourtant de l’artiste collectionneur qu’une vision centrée sur un parcours individuel. Notre contribution a ainsi pour objectif de considérer l’artiste collectionneur [1] sur une période élargie, de la seconde moitié du XIX siècle – période d’intense développement du collectionnisme – à aujourd’hui, grâce aux archives disponibles. Quelles sont-elles ? Que nous révèlent les archives des artistes collectionneurs ? En quoi ces sources nous permettent-elles de reconsidérer le mythe de l’artiste solitaire et désintéressé de toute considération financière véhiculée par la littérature ? Ce travail a pour but de proposer une typologie chronologique des archives, de mettre en lumière leur pluralité, ainsi que de révéler un artiste collectionneur aux multiples facettes. L’inventaire après décès : une liste objective des œuvres détenues par un artiste L’historien de l’art Antoine Schnapper soulevait déjà la difficulté méthodologique du sujet des collections d’artistes (Schnapper, 2001). S’appuyant sur les artistes du XVII siècle, il a mis en exergue l’une des principales sources d’informations pour cette période qu’est l’inventaire après décès. -

Gols Placed Burning Timber Against the Thick Walls, and Those Inside Were Asphyxiated. the Dormition Cathedral Was Again Damaged

gols placed burning timber against the thick walls, and those inside were asphyxiated. Te Dormition Cathedral was again damaged during a large Tatar raid at the beginning of the ffteenth century. Nonetheless, the basic form of both cathedrals remained despite repairs and modifcations. For the Cathedral of Saint Demetrius, a turning point occurred in 1834 during a visit of Tsar Nicholas I. Alarmed by the dilapidated appearance of the Saint Demetrius Cathedral, the tsar ordered a restoration of the shrine to its “original form.” Tat form, however, was determined with less than scholarly rigor, with the consequent demolition in 1837–39 of parts deemed The Ancient Heartland 43 to be ancillary. Tese included a bell tower attached to the VLADIMIR Cathedral of Saint northwest corner as well as an exterior gallery that con- Demetrius. Southwest view. PROKUDIN- GORSKY 21275. tained stairs to the upper level and buttressed the struc- SUMMER 1911. ture on the south, west, and north sides. After this removal, many stone blocks were replaced with new carvings (par- VLADIMIR Cathedral of Saint ticularly in the arcade friezes), and the order of some of the Demetrius. Southwest view. blocks was rearranged. BRUMFIELD, JULY 18, 2009. Tese modifcations enhanced the perception of the facade carving, but valuable details were lost for lack of proper documentation. Furthermore, a renovation of the interior in 1840–47 led to the loss or overpainting of early 44 Chapter One SUZDAL Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin bell SUZDAL Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin tower and Archbishop’s Residence. Northwest view.