Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTHROPOD COMMUNITIES and PASSERINE DIET: EFFECTS of SHRUB EXPANSION in WESTERN ALASKA by Molly Tankersley Mcdermott, B.A./B.S

Arthropod communities and passerine diet: effects of shrub expansion in Western Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors McDermott, Molly Tankersley Download date 26/09/2021 06:13:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/7893 ARTHROPOD COMMUNITIES AND PASSERINE DIET: EFFECTS OF SHRUB EXPANSION IN WESTERN ALASKA By Molly Tankersley McDermott, B.A./B.S. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks August 2017 APPROVED: Pat Doak, Committee Chair Greg Breed, Committee Member Colleen Handel, Committee Member Christa Mulder, Committee Member Kris Hundertmark, Chair Department o f Biology and Wildlife Paul Layer, Dean College o f Natural Science and Mathematics Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Across the Arctic, taller woody shrubs, particularly willow (Salix spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and alder (Alnus spp.), have been expanding rapidly onto tundra. Changes in vegetation structure can alter the physical habitat structure, thermal environment, and food available to arthropods, which play an important role in the structure and functioning of Arctic ecosystems. Not only do they provide key ecosystem services such as pollination and nutrient cycling, they are an essential food source for migratory birds. In this study I examined the relationships between the abundance, diversity, and community composition of arthropods and the height and cover of several shrub species across a tundra-shrub gradient in northwestern Alaska. To characterize nestling diet of common passerines that occupy this gradient, I used next-generation sequencing of fecal matter. Willow cover was strongly and consistently associated with abundance and biomass of arthropods and significant shifts in arthropod community composition and diversity. -

Caterpillars Moths Butterflies Woodies

NATIVE Caterpillars Moths and utter flies Band host NATIVE Hackberry Emperor oodies PHOTO : Megan McCarty W Double-toothed Prominent Honey locust Moth caterpillar Hackberry Emperor larva PHOTO : Douglas Tallamy Big Poplar Sphinx Number of species of Caterpillars n a study published in 2009, Dr. Oaks (Quercus) 557 Beeches (Fagus) 127 Honey-locusts (Gleditsia) 46 Magnolias (Magnolia) 21 Double-toothed Prominent ( Nerice IDouglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D, chair of the Cherries (Prunus) 456 Serviceberry (Amelanchier) 124 New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus) 45 Buttonbush (Cephalanthus) 19 bidentata ) larvae feed exclusively on elms Department of Entomology and Wildlife Willows (Salix) 455 Larches or Tamaracks (Larix) 121 Sycamores (Platanus) 45 Redbuds (Cercis) 19 (Ulmus), and can be found June through Ecology at the University of Delaware Birches (Betula) 411 Dogwoods (Cornus) 118 Huckleberry (Gaylussacia) 44 Green-briar (Smilax) 19 October. Their body shape mimics the specifically addressed the usefulness of Poplars (Populus) 367 Firs (Abies) 117 Hackberry (Celtis) 43 Wisterias (Wisteria) 19 toothed shape of American elm, making native woodies as host plants for our Crabapples (Malus) 308 Bayberries (Myrica) 108 Junipers (Juniperus) 42 Redbay (native) (Persea) 18 them hard to spot. The adult moth is native caterpillars (and obviously Maples (Acer) 297 Viburnums (Viburnum) 104 Elders (Sambucus) 42 Bearberry (Arctostaphylos) 17 small with a wingspan of 3-4 cm. therefore moths and butterflies). Blueberries (Vaccinium) 294 Currants (Ribes) 99 Ninebark (Physocarpus) 41 Bald cypresses (Taxodium) 16 We present here a partial list, and the Alders (Alnus) 255 Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya) 94 Lilacs (Syringa) 40 Leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne) 15 Honey locust caterpillar feeds on honey number of Lepidopteran species that rely Hickories (Carya) 235 Hemlocks (Tsuga) 92 Hollies (Ilex) 39 Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron) 15 locust, and Kentucky coffee trees. -

SYSTEMATICS of the MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

SYSTEMATICS OF THE MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sibyl Rae Bucheli, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John W. Wenzel, Advisor Dr. Daniel Herms Dr. Hans Klompen _________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Passoa Advisor Graduate Program in Entomology ABSTRACT The phylogenetics, systematics, taxonomy, and biology of Gelechioidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) are investigated. This superfamily is probably the second largest in all of Lepidoptera, and it remains one of the least well known. Taxonomy of Gelechioidea has been unstable historically, and definitions vary at the family and subfamily levels. In Chapters Two and Three, I review the taxonomy of Gelechioidea and characters that have been important, with attention to what characters or terms were used by different authors. I revise the coding of characters that are already in the literature, and provide new data as well. Chapter Four provides the first phylogenetic analysis of Gelechioidea to include molecular data. I combine novel DNA sequence data from Cytochrome oxidase I and II with morphological matrices for exemplar species. The results challenge current concepts of Gelechioidea, suggesting that traditional morphological characters that have united taxa may not be homologous structures and are in need of further investigation. Resolution of this problem will require more detailed analysis and more thorough characterization of certain lineages. To begin this task, I conduct in Chapter Five an in- depth study of morphological evolution, host-plant selection, and geographical distribution of a medium-sized genus Depressaria Haworth (Depressariinae), larvae of ii which generally feed on plants in the families Asteraceae and Apiaceae. -

Download Download

Journal Journal of Entomological of Entomological and Acarologicaland Acarological Research Research 2020; 2012; volume volume 52:9304 44:e INSECT ECOLOGY Update to the “Catalogue of Lepidoptera Tortricidae of the Italian Fauna” (2003-2020) P. Trematerra Department of Agricultural, Environmental and Food Sciences, University of Molise, Italy List of taxa Tortricidae Abstract Subfamily Tortricinae In the paper are reported 37 species to add at the “Catalogue of Lepidoptera Tortricidae of the Italian fauna” published on 2003. Tribe Cochylini After this paper the list of tortricids found in Italy passed from 633 to 670 species. Phtheochroa reisseri Razowski, 1970 GEONEMY. Europe (France, Italy, ex-Yugoslavia, Crete). CHOROTYPE. S-European. DISTRIBUTION IN ITALY. Abruzzo: Rivoli and Aschi, L’Aquila Introduction (Pinzari et al., 2006) BIOLOGICAL NOTES. Adults were collected in May. The “Catalogue of Lepidoptera Tortricidae of the Italian fauna” IDENTIFICATION. Morphology of the adult and genital characters published on 2003 as supplement of the Bollettino di Zoologia are reported by Razowski (2009). agraria e di Bachicoltura, reported 633 species (Trematerra, 2003). In these last years tortricids from the Italian territory received atten- Cochylimorpha scalerciana Trematerra, 2019 tion by both local and foreign entomologists that also studied many GEONEMY. Europe (Italy: Calabria) collections deposited in various museums, increasing the faunistic CHOROTYPE. S-Appenninic. knowledge with the recording and description of new taxa. DISTRIBUTION IN ITALY. Calabria: various locations of the Monti In the present paper are reported 37 species to add at the della Sila, Cosenza (Trematerra, 2019a). “Catalogue”, after this paper the list of tortricids found in Italy BIOLOGICAL NOTES. Adults were found in May. -

Japanese Persimmons

RES. BULL PL. PROT. JAPAN No. 31 : 67 - 73 (1995) Methyl Bromide Fumigation for Quarantine Control of Persimmon Fruit Moth and Yellow Peach Moth on Japanese Persimmons Sigemitsu TOMOMATSU, Tadashi SAKAGUCHI*, Tadashi OGlNO and Tadashi HlRAMATSU Kobe Plant Protection Station Takashi Misumi** and Fusao KAWAKAMI Chemical & Physical Control Laboratory, Research Division, Yokohama Plant Protection Station Abstract : Susceptibility of mature larvae of persimmon fruit moth (PFM) , Stathmopoda masinissa MEYRICK, and egg and larval stages of yellow peach moth (YPM) , Conogethes punctiferalis (GUENEE) to methyl bromide (MB) fumigation for 2 hours at 15℃ showed that mature larvae of PFM were the most resistant (LD50: 15.4-16.4 g/m3, LD95: 23.9-26.1 g/m3) of other stages of YPM (2-day-oId egg; LD50:13.5 g/m3, LD95: 19.4 g/m3, 5-day-oId egg; LD50:4.1 g/m3, LD95: 8.4 g/m3 and Larvae; LD50: 5.0-7.7 g/m3 LD95: 8.8-12.3 g/m3) . A 100% mortality for mature larvae of PFM in Japanese persimmons "Fuyu", Diospyros kaki THUNB. in plastic field bins was attained with fumigation standard of 48 g/m3 MB for 2 hours at 15℃ with 49.1-51.9% Ioading in large-scale mortality tests. Key words : Insecta, Stathmopoda masinissa. Conogethes punctiferalis, quarantine treatment, methyl bromide, Japanese persimmons Introduction Japanese persimmons, Diospyros kaki THUNB. are produced mainly in the Central and West- ern regions in Japan which include such prefectures as Gifu, Aichi, Nara, Wakayama, Ehime and Fukuoka. The total weight of commercial crops for persimmons in 1989 was 265,700 tons. -

Sex Pheromone Components in the New Zealand Greenheaded Leafroller Planotortrix Excessana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) R

Sex Pheromone Components in the New Zealand Greenheaded Leafroller Planotortrix excessana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) R. A. Galbreath Entomology Division, D.S.I.R., Private Bag, Auckland, New Zealand M. H. Benn Chemistry Department, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, on leave at Entomology Divi sion, D.S.I.R. H. Young Horticulture and Processing Division, D.S.I.R., Auckland, New Zealand V. A. Holt Entomology Division, D.S.I.R., Auckland, New Zealand Z. Naturforsch. 40 c, 266-271 (1985); received October 30, 1984 Sex Pheromone, Tetradecenyl Acetates, Planotortrix excessana, Tortricidae, Sibling Species Planotortrix excessana was found to include moths of two distinct pheromone-types which were not mutually attractive. Tetradecyl acetate and (Z)-8-tetradecenyl acetate were identified as pheromone components in one, and two other tetradecenyl acetates, probably (Z)-5- and (Z)-7- tetradecenyl acetate, in the other. By contrast with other pheromones reported from the tribe Archipini, A 11-tetradecenyl compounds were not found in either pheromone-type. Introduction locally available host plant, Acmena smithii (Poiret), The greenheaded leafroller, Planotortrix exces in place of alfalfa leaf meal. Pupae were removed, sana (Walker), along with the brownheaded leaf sexed, and separated accordingly. Pheromone ex roller Ctenopseustis obliquana (Walker) and the tract was collected from virgin female moths as light-brown apple moth Epiphyas postvittana (Walker) previously described [4], Male moths were main are predominant among the complex of leafroller tained separately under a natural light cycle until pests of horticulture in New Zealand. All three required for bioassay. moths are classified in the Tortricidae, subfamily Electroantennogram (EAG) responses of antennae Tortricinae, tribe Archipini [1]. -

Differences in the Phenolic Profile by UPLC Coupled to High Resolution

antioxidants Article Differences in the Phenolic Profile by UPLC Coupled to High Resolution Mass Spectrometry and Antioxidant Capacity of Two Diospyros kaki Varieties Adelaida Esteban-Muñoz 1,2,*, Silvia Sánchez-Hernández 1,2, Cristina Samaniego-Sánchez 1,3 , Rafael Giménez-Martínez 1,3 and Manuel Olalla-Herrera 1,3 1 Departamento de Nutrición y Bromatología, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] (S.S.-H.); [email protected] (C.S.-S.); [email protected] (R.G.-M.); [email protected] (M.O.-H.) 2 Programme in Nutrition and Food Science, University of Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain 3 Biosanitary Research Institute, IBS, 18071 Granada, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-958-243-863 Abstract: Background: phenolic compounds are bioactive chemical species derived from fruits and vegetables, with a plethora of healthy properties. In recent years, there has been a growing inter- est in persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.f.) due to the presence of many different classes of phenolic compounds. However, the analysis of individual phenolic compounds is difficult due to matrix interferences. Methods: the aim of this research was the evaluation of individual phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of the pulp of two varieties of persimmon (Rojo Brillante and Triumph) by an improved extraction procedure together with a UPLC-Q-TOF-MS platform. Results: the phenolic compounds composition of persimmon was characterized by the presence of hydroxybenzoic and hy- droxycinnamic acids, hydroxybenzaldehydes, dihydrochalcones, tyrosols, flavanols, flavanones, and Citation: Esteban-Muñoz, A.; flavonols. A total of 31 compounds were identified and 17 compounds were quantified. Gallic acid was Sánchez-Hernández, S.; Rojo Brillante Samaniego-Sánchez, C.; the predominant phenolic compounds found in the variety (0.953 mg/100 g) whereas the Giménez-Martínez, R.; concentration of p-hydroxybenzoic acid was higher in the Triumph option (0.119 mg/100 g). -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 1988 Band/Volume: 11 Autor(en)/Author(s): Razowski Josef [Jozef] Artikel/Article: Miscellaneous notes on Tortricidae 285-289 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Nota lepid. 11 (4) : 285-289 ; 31.1.1989 ISSN 0342-7536 Miscellaneous notes on Tortricidae Jôzef Razowski Institute of Systematic and Experimental Zoology, P.A.S. 31-016 Krakow, Släwkowska 17, Poland. Summary Synonymical notes on several genera and species of Tortricidae are given. Stenop- teron, a new Cnephasiini genus is described. Phtheochroa undulata (Danilevskij, 1962), comb. n. This species was described on the basis of a single female from Central Asia (Dshungarian Ala-Tau). A specimen collected by Dr. Z. Kaszab, Buda- pest, in Mongolia (Gobi Altai aimak : Baga nuuryn urd els, 1200 m., 12.VII.1966) has almost identical wing markings as the holotype of undu- lata. Its male genitalia (Figs 1, 2) are characterised as follows. Uncus fairly short, tapering terminally ; socius broad, sublateral ; sacculus strong, ven- trally convex, with long subapical process ; median part of transtilla so- mewhat expanded dorsally, without any spines ; aedeagus as in Ph. pulvillana (H.-S.), but distal process of juxta absent. The described specimen is most probably conspecific with undulata. Acleris kuznetsovi nom. n. Croesia 6/co/orKuzNETSOV, 1964, Ent. Obozr. 43 : 879, junior secondary homonym of Acleris bicolor Kawabe, 1963, Trans, lep. Soc. Japan 14 : 70. The name bicolor became a junior homonym when Croesia Hübner was synonymised with Acleris Hübner (Razowski, 1987). -

Pp. 72-75, 2020 Download

T REPRO N DU The International Journal of Plant Reproductive Biology 12(1) Jan., 2020, pp.72-75 LA C P T I F V O E B Y T I DOI 10.14787/ijprb.2020 12.1. O E I L O C G O S I S T E S H Floral anatomy and flower visitors of three persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) T varieties cultivated in Central Europe Virág Andor and Ágnes Farkas* Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Pécs, H-7624 Pécs, Rókus str. 2., Hungary *e-mail : [email protected] Received : 20.12.2019; Accepted and Published online: 31.12.2019 ABSTRACT We report flower and pollination biological traits of three persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) varieties cultivated under suboptimal conditions in the temperate climate of Central Europe. In order to observe flower visiting insects and floral morphology, and to determine the nectar producing capacity of persimmon flowers, field studies were conducted in 2018 and 2019. The anatomical studies were performed with light microscopy. Quantitative floral traits were analysed with two-sample t-test. The main flower visitors were honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) and bumblebees (Bombus sp.), which can act as pollinators, while searching for nectar. The studied persimmon varieties belong to the gynoecious type, the solitary pistillate flowers consisting of four- membered calyx and corolla, reduced androecium and a pistil with superior ovary and 3 to 5 stigmata. The size of the calyx was significantly different in different varieties, but corolla diameter did not differ within the same year of study. The diameter of both the calyx and corolla of the same variety was bigger in 2019 compared to 2018, due to favourable climatic conditions. -

Sphaleroptera Alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): a Species Complex

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Veröffentlichungen des Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 86 Autor(en)/Author(s): Whitebread Steven Artikel/Article: Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): a species complex. 177-204 © Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Veröffentlichungen des Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum 86/2006 Innsbruck 2006 177-204 Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): a species complex Steven Whitebread Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): Ein Spezies Komplex Summary Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) is a locally common day-flying high Alpine species previously considered to oeeur in the German, Austrian, Swiss, Italian and French Alps, and the Pyrenees. The females have reduced wings and cannot fly. However, a study of material from the known ränge of the species has shown that "Sphaleroptera alpi- colana" is really a complex of several taxa. S. alpicolana s.str. oecurs in the central part of the Alps, in Switzerland, Italy, Austria and Germany. A new subspecies, S. a. buseri ssp.n. is described from the Valais (Switzerland). Four new species are described, based on distinet differences in the male and female genitalia: S. occiclentana sp.n., S. adamel- loi sp.n.. S. dentana sp.n. and .S'. orientana sp.n., with the subspecies S. o. suborientana. Distribution maps are giv- en for all taxa and where known, the early stages and life histories are described. The role of the Pleistocene glacia- tions in the speciation process is discussed. Zusammenfassung Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) ist eine lokal häufige, Tag fliegende, hochalpine Art, bisher aus den deut- schen, österreichischen, schweizerischen, italienischen und französischen Alpen, und den Pyrenäen bekannt. -

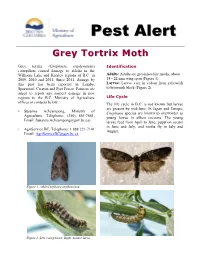

Grey Tortrix Moth

PPeesstt AAlleerrtt GGrreeyy TToorrttrriixx MMootthh Grey tortrix (Cnephasia stephensiana) Identification caterpillars caused damage to alfalfa in the Williams Lake and Kersley regions of B.C. in Adults: Adults are greyish-white moths, about 2009, 2010 and 2011. Since 2011, damage by 18 - 22 mm wing span (Figure 1). this pest has been reported in Lumby, Larvae: Larvae vary in colour from yellowish Sparwood, Creston and Fort Fraser. Farmers are to brownish black (Figure 2). asked to report any suspect damage in new regions to the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture Life Cycle offices or contacts below: The life cycle in B.C. is not known but larvae are present by mid-June. In Japan and Europe, • Susanna Acheampong, Ministry of Cnephasia species are known to overwinter as Agriculture, Telephone: (250) 861-7681, young larvae in silken cocoons. The young Email: [email protected]) larvae feed from April to June, pupation occurs in June and July, and moths fly in July and • AgriService BC, Telephone: 1 888 221-7141 August. Email: [email protected] Figure 1. Adult Cnephasia stephensiana Figure 2. Left, young larva; Right, mature larva Damage On alfalfa, larvae feed by mining leaves and later live in spun or folded leaves (Figure 3). Hosts Hosts include alfalfa, legumes and weeds such as lambs quarters, hogweed, thistle, broad leaf plantain, dock, sorrel, dandelion and clover. In B.C., damage has been reported on alfalfa, cow parsnip, rhodiola, dandelion, clover, hogweed and pea vine. Control There are currently no registered chemical control products in Canada for this pest. -

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and Evolutionary Correlates of Novel Secondary Sexual Structures

Zootaxa 3729 (1): 001–062 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3729.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CA0C1355-FF3E-4C67-8F48-544B2166AF2A ZOOTAXA 3729 Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures JASON J. DOMBROSKIE1,2,3 & FELIX A. H. SPERLING2 1Cornell University, Comstock Hall, Department of Entomology, Ithaca, NY, USA, 14853-2601. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, T6G 2E9 3Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by J. Brown: 2 Sept. 2013; published: 25 Oct. 2013 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 JASON J. DOMBROSKIE & FELIX A. H. SPERLING Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures (Zootaxa 3729) 62 pp.; 30 cm. 25 Oct. 2013 ISBN 978-1-77557-288-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-289-3 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2013 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2013 Magnolia Press 2 · Zootaxa 3729 (1) © 2013 Magnolia Press DOMBROSKIE & SPERLING Table of contents Abstract . 3 Material and methods . 6 Results . 18 Discussion . 23 Conclusions . 33 Acknowledgements . 33 Literature cited . 34 APPENDIX 1. 38 APPENDIX 2. 44 Additional References for Appendices 1 & 2 . 49 APPENDIX 3. 51 APPENDIX 4. 52 APPENDIX 5.