Kossuth Images and Their Contexts, 1848-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Nemzetiségi Kérdés Kossuth És Kortársai Szemében

A nemzetiségi kérdés Kossuth és kortársai szemében BELVEDERE Kiskönyvtár 15. A nemzetiségi kérdés Kossuth és kortársai szemében KISKÖNYVTÁR 15. A nemzetiségi kérdés Kossuth és kortársai szemében Szerkesztette: Kiss Gábor Ferenc Zakar Péter BM#EDERE Szeged, 2003 A kötet megjelenését támogatták Nemzeti Kulturális Örökség Minisztériuma ^ y Oktatási Minisztérium Szegedi Tudományegyetem SZTE Juhász Gyula Tanárképző Főiskolai Kar SZTE JGYTFK HÖK SZTE EHÖK Kulturális Bizottság IV. Béla Kör Magyar Történelmi Társulat Csongrád megyei és Szegedi Csoportja Szegedért Alapítvány Szegedi Román Kisebbségi Önkormányzat Magyarországi Románok Országos Szövetsége NEMZETI KULTURÁLIS ÖRÖKSÉG MINISZTÉRIUMA Kossuth Emlékév Titkársága ! SZTE Egyetemi Könyvtár ISBN 963 8624 6 X ISSN 1217-3495 © Belvedere Méridionale, 2003 Beköszöntő Számtalan példa volt rá, hogy amikor Rákóczi kiáltványáról felelt a hallga- tó, a hangzatos fordítással - „Megújultanak a dicső magyar nemzet se- bei"-adta vissza a „Recrudescunt inclitae gentis Hungáriáé vulnera" kez- dő szavakat. Ilyenkor mindig ki kellett javítanom, hogy az eredetiben bizony másképpen van. Rákóczi ugyanis nagyon is tisztában volt az ország etnikai sokszínűségével, ezért választékosan és precízen fogalmazott, ami- kor Hungária „dicső népének" sebeiről beszélt. Ez a - középkorból jól adatolható, öntudatos - Hungarus szemlélet azonban a nemzetiségek „ön- tudatra" ébredésének időszakában elhalványult, sőt - egyesek szemében - teljesen korszerűtlenné vált. Erről a változásról azonban a magyar poli- tikusi garnitúra sem -

56 Stories Desire for Freedom and the Uncommon Courage with Which They Tried to Attain It in 56 Stories 1956

For those who bore witness to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, it had a significant and lasting influence on their lives. The stories in this book tell of their universal 56 Stories desire for freedom and the uncommon courage with which they tried to attain it in 56 Stories 1956. Fifty years after the Revolution, the Hungar- ian American Coalition and Lauer Learning 56 Stories collected these inspiring memoirs from 1956 participants through the Freedom- Fighter56.com oral history website. The eyewitness accounts of this amazing mod- Edith K. Lauer ern-day David vs. Goliath struggle provide Edith Lauer serves as Chair Emerita of the Hun- a special Hungarian-American perspective garian American Coalition, the organization she and pass on the very spirit of the Revolu- helped found in 1991. She led the Coalition’s “56 Stories” is a fascinating collection of testimonies of heroism, efforts to promote NATO expansion, and has incredible courage and sacrifice made by Hungarians who later tion of 1956 to future generations. been a strong advocate for maintaining Hun- became Americans. On the 50th anniversary we must remem- “56 Stories” contains 56 personal testimo- garian education and culture as well as the hu- ber the historical significance of the 1956 Revolution that ex- nials from ’56-ers, nine stories from rela- man rights of 2.5 million Hungarians who live posed the brutality and inhumanity of the Soviets, and led, in due tives of ’56-ers, and a collection of archival in historic national communities in countries course, to freedom for Hungary and an untold number of others. -

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: the Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: The Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918 MICHAEL LAURENCE MILLER WO OF THE MOST ICONIC PHOTOS of the 1956 Hungarian revolution involve a colossal statue of Stalin, erected in 1951 and toppled on the first day of the anti-Soviet uprising. TOne of these pictures shows Stalin’s decapitated head, abandoned in the street as curious pedestrians amble by. The other shows a tall stone pedestal with nothing on it but a lonely pair of bronze boots. Situated near Heroes’ Square, Hungary’s national pantheon, the Stalin statue had served as a symbol of Hungary’s subjugation to the Soviet Union; and its ceremonious and deliberate destruction provided a poignant symbol for the fall of Stalinism. Thirty-eight years before, at the beginning of an earlier Hungarian revolution, another despised statue was toppled in Budapest, also marking a break from foreign subjugation, albeit to a different power. Unlike the Stalin statue, which stood for only five years, this statue—the so-called Hentzi Monument—had been “a splinter in the eye of the [Hungarian] nation” for sixty-six years. Perceived by many Hungarians as a symbol of “national humiliation” at the hands of the Habsburgs, the Hentzi Monument remained mired in controversy from its unveiling in 1852 until its destruction in 1918. The object of street demonstrations and parliamentary disorder in 1886, 1892, 1898, and 1899, and the object of a failed “assassination” attempt in 1895, the Hentzi Monument was even implicated in the fall of a Hungarian prime minister. -

HSR Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018)

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) In this volume: Jason Kovacs reviews the history of the birth of the first Hungarian settlements on the Canadian Prairies. Aliaksandr Piahanau tells the story of the Hungarian democrats’ relations with the Czechoslovak authorities during the interwar years. Agatha Schwartz writes about trauma and memory in the works of Vojvodina authors László Végel and Anna Friedrich. And Gábor Hollósi offers an overview of the doctrine of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Plus book reviews by Agatha Schwartz and Steven Jobbitt A note from the editor: After editing this journal for four-and-a-half decades, advanced age and the diagnosis of a progressive neurological disease prompt me to resign as editor and producer of this journal. The Hungarian Studies Review will continue in one form or another under the leadership of Professors Steven Jobbitt and Árpád von Klimo, the Presidents res- pectively of the Hungarian Studies Association of Canada and the Hungarian Studies Association (of the U.S.A.). Inquiries regarding the journal’s future volumes should be directed to them. The contact addresses are the Departments of History at (for Professor Jobbitt) Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, RB 3016, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, P7B 5E1. [email protected] (and for Prof. von Klimo) the Catholic University of America, 620 Michigan Ave. NE, Washing- ton DC, USA, 20064. [email protected] . Nándor Dreisziger Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) Contents Articles: The First Hungarian Settlements in Western Canada: Hun’s Valley, Esterhaz-Kaposvar, Otthon, and Bekevar JASON F. -

Hungarisn Studies Review

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) In this volume: Jason Kovacs reviews the history of the birth of the first Hungarian settlements on the Canadian Prairies. Aliaksandr Piahanau tells the story of the Hungarian democrats’ relations with the Czechoslovak authorities during the interwar years. Agatha Schwartz writes about trauma and memory in the works of Vojvodina authors László Végel and Anna Friedrich. And Gábor Hollósi offers an overview of the doctrine of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Plus book reviews by Agatha Schwartz and Steven Jobbitt A note from the editor: After editing this journal for four-and-a-half decades, advanced age and the diagnosis of a progressive neurological disease prompt me to resign as editor and producer of this journal. The Hungarian Studies Review will continue in one form or another under the leadership of Professors Steven Jobbitt and Árpád von Klimo, the Presidents res- pectively of the Hungarian Studies Association of Canada and the Hungarian Studies Association (of the U.S.A.). Inquiries regarding the journal’s future volumes should be directed to them. The contact addresses are the Departments of History at (for Professor Jobbitt) Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, RB 3016, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, P7B 5E1. [email protected] (and for Prof. von Klimo) the Catholic University of America, 620 Michigan Ave. NE, Washing- ton DC, USA, 20064. [email protected] . Nándor Dreisziger Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) Contents Articles: The First Hungarian Settlements in Western Canada: Hun’s Valley, Esterhaz-Kaposvar, Otthon, and Bekevar JASON F. -

Download This Report

STRUGGLING FOR ETHNIETHNICC IDENTITYC IDENTITY Ethnic Hungarians in PostPostPost-Post---CeausescuCeausescu Romania Helsinki Watch Human Rights Watch New York !!! Washington !!! Los Angeles !!! London Copyright 8 September 1993 by Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-115-0 LCCN: 93-80429 Cover photo: Ethnic Hungarians, carrying books and candles, peacefully demonstrating in the central Transylvanian city of Tîrgu Mure’ (Marosv|s|rhely), February 9-10, 1990. The Hungarian and Romanian legends on the signs they carry read: We're Demonstrating for Our Sweet Mother Tongue! Give back the Bolyai High School, Bolyai University! We Want Hungarian Schools! We Are Not Alone! Helsinki Watch Committee Helsinki Watch was formed in 1978 to monitor and promote domestic and international compliance with the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Accords. The Chair is Jonathan Fanton; Vice Chair, Alice Henkin; Executive Director, Jeri Laber; Deputy Director, Lois Whitman; Counsel, Holly Cartner and Julie Mertus; Research Associates, Erika Dailey, Rachel Denber, Ivana Nizich and Christopher Panico; Associates, Christina Derry, Ivan Lupis, Alexander Petrov and Isabelle Tin- Aung. Helsinki Watch is affiliated with the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, which is based in Vienna, Austria. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some sixty countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process of law and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. -

POPORULUI Lmnineazâ-Fe

Lmnineazâ-fe ţfi vei fi! — Voest« şi vei putea! POPORULUI o. A. Лшшсгт 1 1K1UA NICOLAE ІОКСІА 6. A» CL Uli. ,4-Klíí. 75 ГЛІ^ Prim-weacwr: H BEUACŢIA : STHIDA ЛІСОІЬАК IuRttA Urni в. B 4 | •« S II11mîliai'U *> 4піУІі<і# IQ^M I Ai»SII*lSlbA 11\ : ft TELEFON No. 15-75. Apare In flecare Dumineci Avram Iancu şi I¥. Bălcescu Avram Iancu şi M. SL Regele Ferdinand Dosarele trecutului Aceste două figuri luminoa Alba-Iulia, ducea scrisoarea ur Acolo nade simţirea naţionale delà 1848, Am petrecut şi eu îu vara aceasta unei vieţi de sat din Ardealul anilor se ale istoriei noastre au ajuns, mătoare lui Kossuth: romanească vibrează în Ardeal, omul pro câteva zile la o baie modestă din revoluţiei Iui Iancu. bi toiul evenimentelor măreţ* „Văzând propunerile de pace, puternic şi se mani videnţial care a Ardeal. Baie cunoscută şi pe vremea Acum în preajma marilor serbări festă cu emoţia ce trecut la fapte pe din anul 1849 să stea alături. pe cari ni le-a adus d-1 Băl Romanilor vechi, dar mai puţin cu de prăznuire a memoriei lui Iancu, am numai îu moment? le I ' calea armelor şi prin noscută acum în vremea Românilor cetit cu deosebit interes paginile preo Inflăcăratul naţionalist de peste cescu, agentul emigraţiei româ ne din partea guvernului un hotăiîtoare din viaţa 1 el, poporul român — noui. Aci puţina lume^ce se adună, tului de sub poala munţilor lui Iancu, Carpaţi după-ce a luptat cu to gar, trebue să ne exprimăm pă* паеі naţiuni le pot I deşi de puţină înde- de dragul isvoarelor rermale, cu un şi nu fără mulţămire. -

STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS MOLDAVIAE, 2018, Nr.10(120) Seria “{Tiin\E Umanistice” ISSN 1811-2668 ISSN Online 2345-1009 P.76-82

STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS MOLDAVIAE, 2018, nr.10(120) Seria “{tiin\e umanistice” ISSN 1811-2668 ISSN online 2345-1009 p.76-82 CZU: 94(498) „1848/1849” RĂZBOAIELE UITATE ALE ROMÂNILOR LA 1848-1849 Ela COSMA Institutul de Istorie „George Barițiu” al Academiei Române din Cluj-Napoca Istoriografia română a considerat în mod tradițional că revoluțiile de la 1848 din Țările Române (ca teritorii cuprinse în cadrul și în afara hotarelor României de astăzi) se reflectă cel mai bine prin programele create de revoluționarii transilvăneni, moldoveni și munteni. Dacă istoriografia rusă neagă însăși existența unei revoluții pașoptiste românești, istoriografia maghiară o consideră o contrarevoluție. Între timp, insistând asupra evidentei unități programatice a revolu- țiilor de la 1848 în toate teritoriile românești (dar uitând constant să abordeze „pete albe”, precum Basarabia, Bucovina, Banatul Sârbesc), istoriografia noastră nu a acordat aproape deloc atenție altor aspecte importante. Astfel, componenta militară a revoluțiilor românești de la 1848-1849, în general neglijată de istorici, este prezentată în studiul de față. Acesta abordează operațiunile militare românești desfășurate în cursul anilor pașoptiști în Țările Române, de la bătălii singulare la războiul clasic, de la acțiuni de înarmare populară și de instrucție în tabere militare la lupte de gherilă în munți. În Transilvania, așa-numitul „război civil” româno-ungar a fost, de fapt, un război în toată regula, definit de curând ca fiind un război național de apărare purtat de românii ardeleni. Sunt evidențiate episoade belice mai puțin cunoscute din Valahia Mare și Valahia Mică (Oltenia), precum și rezistența armată din Moldova și tabăra militară de la Grozești (azi Oituz), în Carpații de Curbură. -

A Celebrated, Disillusioned Hungarian Revolutionary's Visit to Pittsburgh in 1852

A Celebrated, Disillusioned Hungarian Revolutionary’s Visit to Pittsburgh in 1852 By Steven B. Várdy, Ph.D. 18 WESTERNPENNSYLVANIA HISTORY | S P R I N G 2 0 0 8 Louis Kossuth, 1802-1894. From Dedication of a Bust of Lajos (Louis) Kossuth, 1990. Courtesy of Hungarian Reformed Federation of America. WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY | S P R I N G 2 0 0 8 19 n Hungary, there is hardly a city, University building. Here, Kossuth and his introduced a form of absolutism. Following town, or village without a Kossuth retinue lodged for nine days and nights.1 the Napoleonic Wars, rising nationalism of Street, a Kossuth Square, a Kossuth One of Kossuth’s great political the Empire’s more than a dozen nationalities Club, or some other institution or undertakings was his nearly eight-month- forced the Habsburg rulers to become more organization named after Louis long visit to the United States: December 4, conciliatory toward Hungary. In 1825 [Lajos]I Kossuth. Of all the prominent 1851-July 14, 1852. He came with the Emperor Francis I (r. 1792-1835) even agreed personalities in Hungarian history, no one is intention of securing American help for to call into session the Hungarian Feudal Diet. better known worldwide than this celebrated resuming his struggle against the Austrian This act initiated Hungary’s Age of Reform leader of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848- Habsburg dynasty, which had ruled Hungary (1825-1848), which ultimately led to the 1849. Even in the United States there are over a for over three centuries.2 In the early 16th Revolution of 1848. -

Mađarska Od Nagodbe 1867. Do 1. Svjetskog Rata

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Mađarska od Nagodbe 1867. do 1. svjetskog rata Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Diplomski studij Povijesti i Hrvatskog jezika i književnosti Ivana Barišić MAĐARSKA OD NAGODBE 1867. DO 1. SVJETSKOG RATA Diplomski rad Mentor: prof.dr.sc. Ivan Balta Osijek, 2012. 0 Mađarska od Nagodbe 1867. do 1. svjetskog rata SAŽETAK Nakon sloma neoapsolutizma car Franjo Josip I. objavio je Listopadsku diplomu (1860.) i Veljački patemt (1861.) kojima je učvršćen centralizam. Porazom Austrije u ratu s Pruskom (1866.) car uspostavlja sporazum s Mađarima te je 1867. godine postignuto sklapanje Nagodbe, kojom je stvorena Austro-Ugarska Monarhija sa središtem u Beču i Budimpešti te su utvrđeni autonomni i zajednički poslovi. Za Andrássyjeve vlade (1867.-1871.) donesen je Zakon o narodnostima (1868.) kojim nisu priznata nacionalna prava nemađarskim narodima u Ugarskoj. Gušenjem seljačkog pokreta Andrássy je pridonio konsolidaciji Dvojne Monarhije. Kao ministar vanjskih poslova istaknuo se stvaranjem fronte Velike Britanije, Francuske i Njemačke, uperene protiv ruskog širenja u jugoistočnoj Europi, te sklapanjem vojnog saveza s Njemačkom (1879.). Kálmán Tisza (1875.-1890.) učvrstio je dualistički sustav, ali je ojačao i netolerantni nacionalizam uz poticanje mađarizacije. Na prijelazu stoljeća mađarsku politiku vodila su tri premijera: Gyula Szapáry (1890.-1892.) provodi zdravstvene i financijske mjere, Sándor Wekerle (1892.-1895.) financijske i vjerske reforme, a za Dezsöa Bánffyja (1895.-1899.) slavilo se tisuću godina mađarskog osvajanja Dunavskog bazena. Godine 1905./1906. nastupila je kriza dualizma koja se očitovala u jačanju parlamentarne oporbe pod vodstvom Stranke neovisnosti. -

The Hungarian Revolutions of 1848 and 1989: a Comparative Study

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 219 SO 034 475 AUTHOR Augsburger, Irene TITLE The Hungarian Revolutions of 1848 and 1989: A Comparative Study. Fulbright-Hayes Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 2002 (Hungary and Poland). SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 6p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Comparative Analysis; *Curriculum Development; *European History; Foreign Countries; Grade 10; High Schools; Political Science; *Revolution; Social Studies; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Hungary ABSTRACT This study unit for grade 10 world history classes helps students understand the economic, social, and political causes and effects of revolution, using the Hungarian Revolutions of 1848 and 1989 as examples. The unit cites an educational goal; lists objectives; provides a detailed procedure for classroom implementation; describes standards; notes materials needed; addresses assessment; and suggests a follow-up activity. Contains five references; a summary of the relevant historical background of Hungary; and a grid representing the causes, demands, and results of the 1848 and the 1989 revolutions. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. The Hungarian Revolutions of 1848 and 1989 A Comparative Study By Irene Augsburger Description: This study unit will help students understand the economic, social and political causes and effects of revolution. 2. Grade Level: 10th grade world history 3.Goal: Students will recognize patterns that lead to revolution in general. They will also analyze cause and effect relationships. 4.Objective: a.) Compare different revolutions b.) Explain similarities and differences c.) Hypothesize the outcome in a specific country d.) Generalize the information 5. -

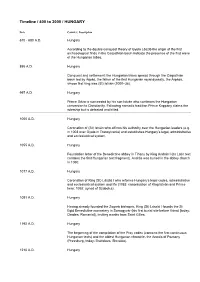

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia).