Spatial Wage Inequality in Belarus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAP-10-GB.Pdf

!"#$%&'()*')' +&&$*'* , ! ! "- ! . / ! , 0 1%- ! " " %12*3- , 4" 5 4 )*)* " - ! . / ! , 0 Boris Zalessky Growth points Features of development in the face of global challenges 1 2 Table of contents Sustainable development goals and media ................................................................................. 5 Global information security and regional press ........................................................................ 12 From strategy to attract foreign investment to international cooperation ................................ 20 Honorary Consuls Institute: project-specific orientation.......................................................... 28 Export culture and mass consciousness .................................................................................... 31 Exports to distant arc countries as an important factor for development ................................. 34 Food exports: growth trends ..................................................................................................... 37 Export of services: among priorities - tourism ......................................................................... 40 Import substitution: growth reserves - in modernization.......................................................... 43 From green economy to green cities........................................................................................ -

Individual V. State: Practice on Complaints with the United Nations Treaty Bodies with Regards to the Republic of Belarus

Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus Volume I Collection of articles and documents The present collection of articles and documents is published within the framework of “International Law in Advocacy” program by Human Rights House Network with support from the Human Rights House in Vilnius and Civil Rights Defenders (Sweden) 2012 UDC 341.231.14 +342.7 (476) BBK 67.412.1 +67.400.7 (4Bel) I60 Edited by Sergei Golubok Candidate of Law, Attorney of the St. Petersburg Bar Association, member of the editorial board of the scientific journal “International justice” I60 “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus”. – Vilnius, 2012. – 206 pages. ISBN 978-609-95300-1-7. The present collection of articles “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus” is the first part of the two-volume book, that is the fourth publication in the series about international law and national legal system of the republic of Belarus, implemented by experts and alumni of the Human Rights Houses Network‘s program “International Law in Advocacy” since 2007. The first volume of this publication contains original writings about the contents and practical aspects of international human rights law concepts directly related to the Institute of individual communications, and about the role of an individual in the imple- mentation of international legal obligations of the state. The second volume, expected to be published in 2013, will include original analyti- cal works on the admissibility of individual considerations and the Republic of Belarus’ compliance with the decisions (views) by treaty bodies. -

WFWP Biennial Report International Service Projects Overseas Volunteer Activities 2017-2018

WFWP Biennial Report International Service Projects Overseas Volunteer Activities 2017-2018 WOMEN’ S FEDERATION FOR WORLD PEACE WOMEN'S FEDERATION FOR WORLD PEACE, INTERNATIONAL UN ECOSOC/DPI/NGO General Consultative Status Department of International Service Projects / WFWP Japan National Headquarters Sansarra Higashiyama Suite 202, 3-1-11 Higashiyama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 153-0043 JAPAN TEL:+81-3-5721-2579 FAX:+81-3-5721-2580 Email:[email protected] Website:https://wfwp.jp(Japanese) https://www.wfwp.org(English) UNDERSTANDING THE DIMENSIONS OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Five dimensions of Sustainable Development Goals(SDGs) POVERTY HUNGER HEALTH EDUCATION GENDER UNEQUALITY ENERGY SOCIAL WATER/ HYGIENE PARTNER- PEACE GROWTH/ SHIP EMPLOYMENT CLIMATE CHANGE SUSTAINABLE ENVIRON- Sustainable ECONOMIC INNOVATION MENTAL MARINE RESOURCES CITY LAND RESOURCES PRODUCTION/ CONSUMPTION By endorsing Agenda 2030 and its 17 goals, the world community has reaffirmed its commitment to Sustainable Development; to ensure sustained and inclusive economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection and to do so in partnership and peace. Sustainable Development is usually viewed through a lens of three core elements: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection. But it’s important to remember that these are not just categories or boxes: they are connected and have aspects in common. To develop this approach a step further, two critical dimensions that will drive Agenda 2030 were adopted by member states: partnership and peace. Partnerships strengthen the capacities of all stakeholders to work together. Peace, justice and strong institutions are essential for improvements in the three core areas. Genuine sustainability sits at the center and it would be important to consider each of the SDGs through the lens of these five dimensions. -

Charniauski the Excavation of Kryvina Peatbog Settlements In

THE EXCAVATION OF KRYVINA PEATBOG SETTLEMENTS IN NORTHERN BELARUS BETWEEN 2000 AND 2009 MICHAL CHARNIAUSKI, MAXIM CHARNIAUSKI The Excavation of Kryvina The Excavation of Kryvina Peatbog Settlements in Northern Belarus between 2000 and 2009 Abstract Between 2000 and 2010, the Asaviec 2 and Asaviec 7 settlements of Kryvina peatbog (Vitebsk region) were excavated. At MICHAL MICHAL CHARNIAUSKI, MAXIM CHARNIAUSKI Asaviec 2 the excavations concentrated on the northern part, where pure materials of Usvyatian culture were found, and also several fragments of a Globular Amphora culture vessel. The excavations of the new Asaviec 7 settlement (up till 2007) gave us pure materials of Northern Belarusian culture, too. Among them are bone, antler and flint items, made mainly according to local Neolithic traditions. There are two 14C dates for this settlement: 3770±90 ВР and 3870±40 ВР. Key words: Late Neolithic, Bronze Age, peatbog settlements, northern Belarus, Usviaty culture, Northern Belarusian culture. Kryvina peatbog is situated on the border of the Sianno one metre was discovered under the peat. Up to and Beshankovichy districts in the Vitebsk region. Ten 0.5 metres deep, it contained artefacts of Northern Neolithic and Bronze Age settlements, Asaviec 1, 2, 3, Belarusian culture. Lower, down to the bedrock, the 4, 5, 6, 7 and Kryvina 1, 2, 3, as well as several other remains of an Usvyatian culture settlement were bed- sites, are known here (Fig. 1). ded in situ. Specific artefacts were found here that rep- resent comprehensively local Usvyatian culture. They Between 2000 and 2009 the settlements of Asaviec 2 comprise ceramics, tools and hunting weapons made (by Michal Charniauski) and Asaviec 7 (by Maxim from flint, horn and bone, household tools, decora- Charniauski) were investigated. -

Contemporary Recordings of Belarusian Folk Biblical and Non-Biblical Etiological Legends in the Comparative-Historical Aspect

https://doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2018.72.boganeva CONTEMPORARY RECORDINGS OF BELARUSIAN FOLK BIBLICAL AND NON-BIBLICAL ETIOLOGICAL LEGENDS IN THE COMPARATIVE-HISTORICAL ASPECT Elena Boganeva Center for Belarusian Culture, Language and Literature Research National Academy of Sciences, Belarus e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The article considers some rare etiologies in contemporary record- ings – non-biblical cosmogonic and folk biblical anthropogenic etiologies in the comparative and historical aspect. Cosmogonic etiologies are stories about the predetermination of spatial and temporal parameters of the world (texts about the origins of the elements of the earthscape, in particular, mountains; about the agreement made between God and Satan concerning the distribution of as- cendancy over people at the beginning of the world and at the end of it; about the determination of the time of the existence of the world and the change of time); about the structure of the current status of the Universe (the Earth is round, it revolves and is supported by a giant turtle or tortoise); about the primary entity or body, from which the following emerges: the world (out of a child’s body), a part of cultural space – a group of inhabited localities (out of a felled statue), and one of the primary elements – fire (out of a human). Anthropogenic folk biblical etiologies include stories about the origins of sexual relations between the first people (two versions); the birth of children out of different body parts (the head, through the side of the body); and the origins of hair on male bodies. Keywords: anthropogenic etiologies, etiological legend, etiologies of cosmogonic legends, folk Bible, folk biblical etiologies, folk narratives, non-biblical etiologies, vernacular Christianity INTRODUCTION According to its administrative division, there are 6 regions (oblasts) and 118 districts in Belarus. -

Emergency Response UNCCD to Drought and Desertification in Belarus

Emergency response UNCCD to drought and desertification in Belarus June 17, Belarus has widely observed the Desertification and Drought Day, a global event which commemorates the entering into force of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification back in 1996. Why land degradation and drought are important topics for Belarus? The warming and prolonged vegetative period caused by climate change bring new opportunities for agriculture, forestry and local people, but more it demonstrates the vulnerability of the land and the need for urgent actions to preserve land fertility. Where do you think these photos were taken? Photo Plytkevič: Arable lands in Gomel Region of Belarus affected by sands storms, April 2020 No, this is not African or Arabian Desert. This is the Republic of Belarus, a country in the center of Europe with a typical Сentral European climate and 40% forest-covered area. Belarusians gently name their country "blue -eyed " for a large number of lakes, more than 10,000. The impact of climate change has now reached Belarus which used to be safe and unharmed by desertification and drought. The average temperature in January 2020 was 1.1 degrees Celsius, which is 5.5 degrees Celsius above the climatic norm. This is the warmest January in the history of weather observations in the country. In the south of the country, Belarusian Polesye, is a unique According to the Institute of wetland landscape, a home of many endangered species of Nature Management of Belarusian birds and animals. Polesyan mires are transit corridor Academy of Sciences, due to offering a safe and food-rich stop for many migratory birds. -

Geographic Structure of Road Transportation and Logistics Infrastructure in the Republic of Belarus

ISSN 1426-5915 e-ISSN 2543-859X 20(2)/2017 Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG 2017, 20(2), 8-18 DOI 10.4467/2543859XPKG.17.007.7389 GeoGraPhic sTrucTure of road TransPorTaTion and loGisTics infrasTrucTure in The rePublic of belarus Struktura geograficzna infrastruktury transportu drogowego i logistyki w Republice Białorusi andrei bezruchonak Department of Economic Geography of Foreign Countries, Faculty of Geography, Belarusian State University, Leningradskaya st. 16, 220030, Minsk, Belarus e-mail: [email protected] citation: Bezruchonak A., 2017, Geographic structure of road transportation and logistics infrastructure in the Republic of Belarus, Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG, 20(2), 8-18. abstract: Transportation, representing 6% of GDP, plays vital role in social and economic development of the Republic of Belarus. The purpose of this article is to present the geographic analysis of current spatial structure of the road transportation in Belarus in 2000-2014. The choice of transport mode for the article was influenced by several factors, such as historic devel- opment, network coverage, transformational changes in productivity, rapid increase in car ownership numbers, emergence of logistic centers and intelligent transportation systems. The article reviews the range of topics, including morphology of the major roads network, logistic centers spatial distribution and regional features of passenger and cargo productivity, discusses current transformational changes within the road transportation sector in Belarus. The key findings indicate that current changes in spatial structure of the road transportation in Belarus have uneven nature, shaped by social, economic, political and geopolitical external and internal factors and are a subject of interest for both transportation researchers and practitioners. -

Vitebsk Tour

Vitebsk tour Our Vitebsk tour will take you to the most important industrial town in the north-east of White Russia. At the confluence of the Visba and the Dvina you will find this old trading metropolis and cosmopolitan centre of arts with a distinctly western flair. Vitebsk can look back on over 1000 years of history, which started in the Kievan Rus. There was a frequent change of ruler in the Middle Ages when it was a trading centre, and each one left his mark on the appearance of the town. The town was Lithuanian, Polish, Russian and the inhabitants were representative of many nations and religions. Napoleon besieged and devastated Vitebsk and by doing so laid the foundation stone for the catastrophic end of his Russian campaign. Vitebsk city center. In Vitebsk, the tramway is everyone’s pride and joy. Vitebsk was the first town in Belarus to have such a form of transport (since 1898). Tramways were introduced at a later date even in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Vitebsk, like many other eastern European towns, was almost completely destroyed in both World Wars and subsequently rebuilt retaining very little of the original historical substance. The town nevertheless still has sights worth seeing. The name of Marc Chagall is inseparable from Vitebsk. He was born in the town and was a world-renowned member of the Russian avant-garde. Vitebsk was the centre of this art style at the beginning the 1920s. Many museums, galleries and monuments in the town focus on Marc Chagall’s life in Vitebsk and his contemporaries, such as Kasimir Malevich and El Lissitsky. -

Part 2: the First Partition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 1772 – Its Description and Depiction in Maps Andrew Kapochunas, Jersey City, New Jersey EN

Historical research article / Lietuvos istorijos tematika The Maps and Mapmakers that Helped Define 20th-Century Lithuanian Boundaries - Part 2: The First Partition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 1772 – Its Description and Depiction in Maps Andrew Kapochunas, Jersey City, New Jersey EN In the previous – and first – installment of this influence of Russia’s military on Empress Catherine II series, we established a geographical starting point for is primary: the dismemberment of the 11 provinces (vaivadijų) “…the military party was openly in favor of direct annexa- of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Lietuvos Didžioji tions. They believed that Russia’s interests could best be Kunigaikštystė) by the Empire of Russia. My inten- served by seizing the territory of her neighbors on every tion was to then focus on the Russian administrative possible occasion. Chernyshev, the Vice-President of the War boundary changes of the lands they acquired. But, as I College, expressed this view when, at the new [as of 1762] reviewed the literature and maps describing the First, Empress Catherine’s council called to discuss the [1763] death 1772, Partition, I was struck by the disparate descrip- of the King of Poland [Augustus III], he proposed an invasion tions and cartographic depictions of that seemingly of Polish Livonia and the palatinates of Polotsk, Witebsk, and straight-forward event. I decided to present a sum- Mscislaw.”2 mary of that event and its immediate aftermath in the annexed regions. The next two articles, then, will Nine years later, those were the areas annexed – and cover the Second (1793) and Third (1795) Partitions. -

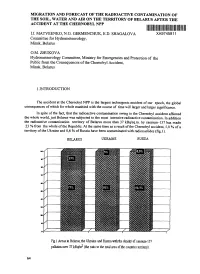

Migration and Forecast of the Radioactive Contamination of the Soil, Water and Air on the Territory of Belarus After the Accident at the Chernobyl Npp

MIGRATION AND FORECAST OF THE RADIOACTIVE CONTAMINATION OF THE SOIL, WATER AND AIR ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS AFTER THE ACCIDENT AT THE CHERNOBYL NPP I.I. MATVEENKO, N.G. GERMENCHUK, E.D. SHAGALOVA XA9745811 Committee for Hydrometeorology, Minsk, Belarus O.M. ZHUKOVA Hydrometeorology Committee, Ministry for Emergencies and Protection of the Public from the Consequences of the Chernobyl Accident, Minsk, Belarus 1.INTRODUCTION The accident at the Chernobyl NPP is the largest technogenic accident of our epoch, the global consequences of which for whole manhind with the course of time will larger and larger significance. In spite of the fact, that the radioactive contamination owing to the Chernobyl accident affected the whole world, just Belarus was subjected to the most intensive radioactive contamination. In addition the radioactive contamination territory of Belarus more than 37 kBq/sq.m. by caesium-137 has made 23 % from the whole of the Republic. At the same time as a result of the Chernobyl accident, 5,0 % of a territory of the Ukraine and 0,6 % of Russia have been contaminated with radionuclides (fig.l). BELARUS UKRAINE RUSSIA Fig. 1 Areas in Belarus, the Ukraine and Russia with the density of caesium-137 pollution over 37 kBq/a^ (tile ratio to the total area of the countries territory). 64 By virtue of a primary direction of movement of air masses, contamination with radionuclides in the northern-western, northern and northern-eastern directions in the initial period after the accident, the significant increase of the exposition doze rate was registered practically on the whole territory of Belarus. -

Review-Chronicle

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 1999 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 1999 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS The year of 1999 was the last year of Alexander Lukashenka’s original mandate. In 1994 having used the machinery of democratic procedure he was elected president of the Republic of Belarus for five years term. But in 1996 A.Lukashenka conducted illegal, non-free and unfair referendum and by it prolonged his mandate to seven years. Constitutional Court’s judges and deputies of the Supreme Soviet that resisted to A.Lukashenka’s dictatorial intentions were dismissed. Thus provisions of the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus were broken. Attempt to conduct presidential elections done by the legitimate Supreme Soviet of the 13th convocation was supported by the most influential opposition parties and movements. But Belarusan authorities did their best to prevent opposition from succeeding in presidential elections and subjected people involved in election campaign to different kinds of repressions. Regime didn’t balk at anything in the struggle with its opponents. Detentions and arrests, persecutions of its organisers and participants, warnings, penalties and imprisonment followed every opposition-organised action… Yet the year of 1999 became a year of mass actions of protest of Belarusan people against a union with Russia imposed by the authorities to the people. In 1999 the OSCE Advisory and Monitoring Group in Belarus made an attempt to arrange talks between Belarusan authorities and opposition. This year will go down to history as a year when some of prominent politicians and fighters against the regime disappeared, when unprecedented number of criminal proceedings against opposition leaders and participants of mass actions of protest was instituted.. -

Subbuteo2020online.Pdf

ПРАВИЛА ДЛЯ АВТОРОВ в списке литературы: книги: Паевский В. А. Демография птиц. — Л., 1985. 1) В сборнике «Subbuteo» публикуются статьи — 285 с. и краткие сообщения по всем проблемам орнитоло- статьи: Ивановский В. В. Прошлое, настоящее и бу- гии, материалы полевых исследований, а также об- дущее сапсана в Беларуси // Труды Зоол. музея БГУ, т. 1 зорные работы. Принимаются рукописи объемом до — Минск, 1995. — С. 295–301. 10 страниц машинописи. Работы более крупного объ- тезисы: Самусенко И. Э. Аистообразные — эталон- ема могут быть приняты к опубликованию при специ- но-индикационная группа птиц // Материалы 10-й альном согласовании с редакционной коллегией. Всесоюзн. орнитол. конф., ч. 2, кн. 2. — Минск, 1991. 2) Статьи объемом более 1 стр. машинописи при- — С. 197–198. нимаются только в электронном варианте. Редакция оставляет за собой право редактирова- 3) Статьи и заметки объемом до 1 стр. принима- ния рукописей. Корректура иногородним авторам не ются либо в электронном, либо в машинописном ва- высылается. Возможно возвращение рукописей на рианте. Текст должен быть напечатан на белой бумаге доработку. стандартного формата А4 (21 х 30 см) через 2 интерва- В одном номере бюллетеня публикуется, как пра- ла, не более 60 знаков в строке и 30 строк на странице. вило, не более двух работ одного автора. Исключение Статьи, сообщения и заметки в рукописном вари- может быть сделано для работ в соавторстве. анте принимаются только в виде исключения от орни- Авторов просим по возможности кроме полного тологов-любителей, студентов и учащихся. почтового адреса указывать номер телефона, адрес 4) Текст работы должен быть оформлен в следую- электронной почты. щем порядке: заглавие (заглавными буквами того же шрифта, что Рукописи направлять по адресу: Гричику В.