Draft Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

RHETORIC and RATIONALITY Steve Mackey

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 9, no. 1, 2013 RHETORIC AND RATIONALITY Steve Mackey ABSTRACT: The dominance of a purist, ‘scientistic’ form of reason since the Enlightenment has eclipsed and produced multiple misunderstandings of the nature, role of and importance of the millennia-old art of rhetoric. For centuries the multiple perspectives conveyed by rhetoric were always the counterbalance to hubristic claims of certainty. As such rhetoric was taught as one of the three essential components of the ‘trivium’ – rhetoric, dialectic and grammar; i.e. persuasive communication, logical reasoning and the codification of discourse. These three disciplines were the legs of the three legged stool on which western civilisation still rests despite the perversion and muddling of the first of these three. This essay explains how the evisceration of rhetoric both as practice and as critical theory and the consequent over- reliance on a virtual cult of rationality has impoverished philosophy and has dangerously dimmed understandings of the human condition. KEYWORDS; Rhetoric; Dialectic; Rationality; Enlightenment; Philosophy; Communication; C.S.Peirce: Max Horkheimer; Theodor Adorno; Jürgen Habermas; John Deely THE PROBLEM There are many criticisms of the rationalist themes and approaches which burgeoned during and since the Enlightenment. This paper enlists Max Horkheimer (1895 – 1973) and Theodor Adorno (1903 – 1969), John Deely (1942 – ) and Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 –1914), along with some leading Enlightenment figures themselves in order to mount a critique of the fate of the millennia-old art of rhetoric during that revolution in ways of thinking. The argument will be that post-Enlightenment over- emphasis on what might variously be called dialectic, logic or reason (narrowly understood) has dulled understanding of what people are and how people think. -

Averroes's Dialectic of Enlightenment

59 AVERROES'S DIALECTIC OF ENLIGHTENMENT. SOME DIFFICULTIES IN THE CONCEPT OF REASON Hubert Dethier A. The Unity ofthe Intellect This theory of Averroes is to be combated during the Middle ages as one of the greatest heresies (cft. Thomas's De unitate intellectus contra Averroystas); it was active with the revolutionary Baptists and Thomas M"Unzer (as Pinkstergeest "hoch liber alIen Zerstreuungen der Geschlechter und des Glaubens" 64), but also in the "AufkHinmg". It remains unclear on quite a few points 65. As far as the different phases of the epistemological process is concerned, Averroes reputes Avicenna's innovation: the vis estimativa, as being unaristotelian, and returns to the traditional three levels: senses, imagination and cognition. As far as the actual abstraction process is concerned, one can distinguish the following elements with Avicenna. 1. The intelligible fonns (intentiones in the Latin translation) are present in aptitude and in imaginative capacity, that is, in the sensory images which are present there; 2. The fonns are actualised by the working of the Active Intellect (the lowest celestial sphere), that works in analogy to light ; 3. The intelligible fonns-in-act are "received" by the "possible" or the "material intellecf', which thereby changes into intellect-in-act, also called: habitual or acquired intellect: the. perfect form ofwhich - when all scientific knowledge that can be acquired, has been acquired -is called speculative intellect. 4. According to the Aristotelian principle that the epistemological process and knowing itselfcoincide, the state ofintellect-in-act implies - certainly as speculative intellect - the conjunction with the Active Intellect. 64 Cited by Ernst Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, (1953), in Suhrkamp, Gesamtausgabe, 7, p. -

Theory, Totality, Critique: the Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 16 Issue 1 Special Issue on Contemporary Spanish Article 11 Poetry: 1939-1990 1-1-1992 Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity Philip Goldstein University of Delaware Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Goldstein, Philip (1992) "Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 16: Iss. 1, Article 11. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/2334-4415.1297 This Review Essay is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity Abstract Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity by Douglas Kellner. Keywords Frankfurt School, WWII, Critical Theory Marxism and Modernity, Post-modernism, society, theory, socio- historical perspective, Marxism, Marxist rhetoric, communism, communistic parties, totalization, totalizing approach This review essay is available in Studies in 20th Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol16/iss1/11 Goldstein: Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Cr Review Essay Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Philip Goldstein University of Delaware Douglas Kellner, Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity. -

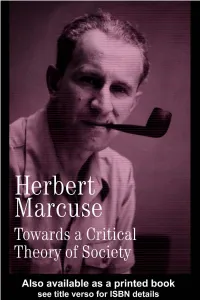

Towards a Critical Theory of Society Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse Edited by Douglas Kellner

TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW LEFT Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Two Edited by Douglas Kellner London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2001 Peter Marcuse Selection and Editorial Matter © 2001 Douglas Kellner Afterword © Jürgen Habermas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marcuse, Herbert, 1898– Towards a critical theory of society / Herbert Marcuse; edited by Douglas Kellner. p. cm. – (Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse; v. 2) Includes bibliographical -

Towards an Understanding of Max Horkheimer Towards an Understanding

TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING OF MAX HORKHEIMER TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING OF MAX HORKHEIMER By JOHN MARSHALL, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by John Marshall, April 1999 MASTER OF ARTS (1999) McMaster University (Philosophy) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Towards an Understanding of Max Horkheimer. AUTHOR: John Marshall, B.A. (University of Regina) SUPERVISOR: Professor Catherine Beattie NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 97. li Abstract Due in large part to the writings of Jurgen Habermas, the philosophy of Max Horkheimer has recently undergone a re-examination. Although numerous thinkers have partaken in this re-examination, much of the discussion has occurred within a framework of debate established by Habermas' narrative of Horkheimer's philosophy. This thesis seeks to broaden that framework through a thorough, critical examination of Habermas' accounts. In chapter one, I survey Habermas' narrative centering on his treatment of the pivotal years in the 1940s. In chapter two, I expand on these years and argue that in contrast to Habermas' assertion that Horkheimer commits a performative contradiction, he instead engages in a logically consistent form of critique. In chapter three I discuss the later writings of Horkheimer and argue that the conception of philosophy contained therein is a continuation of his philosophy of the 1940s. Finally, in the conclusion I point to the implications which the above should have for Horkheimerian studies in general. iii Acknowledgements In a project such as this, a debt of gratitude is owed to a number of individuals without whose patient help, it could never have been completed. -

Downloads/Von Der Gesellschaftssteuerung Zur Sozialen Kontrolle.Pdf 704 the Conference Was Max Weber Und Die Soziologie Heute: Verhandlungen Des 15

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p0574bc Author Callison, William Andrew Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory By William Andrew Callison A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Wendy Brown, Chair Professor Pheng Cheah Professor Kinch Hoekstra Professor Martin Jay Professor Hans Sluga Professor Shannon C. Stimson Summer 2019 Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory Copyright © 2019 William Andrew Callison All rights reserved. Abstract Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory By William Andrew Callison Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Wendy Brown, Chair This dissertation examines the changing relationship between social science, economic governance, and political imagination over the past century. It specifically focuses on neoliberal, ordoliberal and neo-Marxist visions of politics and rationality from the interwar period to the recent Eurocrisis. Beginning with the Methodenstreit (or “methodological dispute”) between Gustav von Schmoller and Carl Menger and the subsequent “socialist calculation debate” about markets and planning, the dissertation charts the political and epistemological formation of the Austrian School (e.g., Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich A. -

Anarchy and Anti-Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition Joaquin A

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-23-2016 Anarchy and Anti-Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition Joaquin A. Pedroso [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000744 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Pedroso, Joaquin A., "Anarchy and Anti-Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2578. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2578 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida ANARCHY AND ANTI-INTELLECTUALISM: REASON, FOUNDATIONALISM, AND THE ANARCHIST TRADITION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Joaquin A. Pedroso 2016 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by Joaquin A. Pedroso, and entitled Anarchy and Anti- Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Paul Warren _______________________________________ Bruce Hauptli _______________________________________ Ronald Cox _______________________________________ Harry Gould _______________________________________ Clement Fatovic, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 23, 2016 The dissertation of Joaquin A. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ENCYCLICAL LETTER SPE SALVI OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF BENEDICT XVI TO THE BISHOPS PRIESTS AND DEACONS MEN AND WOMEN RELIGIOUS AND ALL THE LAY FAITHFUL ON CHRISTIAN HOPE Introduction 1. “SPE SALVI facti sumus”—in hope we were saved, says Saint Paul to the Romans, and likewise to us (Rom 8:24). According to the Christian faith, “redemption”—salvation—is not simply a given. Redemption is offered to us in the sense that we have been given hope, trustworthy hope, by virtue of which we can face our present: the present, even if it is arduous, can be lived and accepted if it leads towards a goal, if we can be sure of this goal, and if this goal is great enough to justify the effort of the journey. Now the question immediately arises: what sort of hope could ever justify the statement that, on the basis of that hope and simply because it exists, we are redeemed? And what sort of certainty is involved here? Faith is Hope 2. Before turning our attention to these timely questions, we must listen a little more closely to the Bible's testimony on hope. “Hope”, in fact, is a key word in Biblical faith—so much so that in several passages the words “faith” and “hope” seem interchangeable. Thus the Letter to the Hebrews closely links the “fullness of faith” (10:22) to “the confession of our hope without wavering” (10:23). Likewise, when the First Letter of Peter exhorts Christians to be always ready to give an answer concerning the logos—the meaning and the reason—of their hope (cf. -

Traditional and Critical Theory

CRITICAL THEORY Selected Essays MAX HORKHEIMER TRANSLATED BY MATTHEW J. O'CONNELL AND OTHERS CONTINUUM • NEW YORK 2002 The Continuum Publishing Company 370 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10017 The essays in this volume originally appeared in book form in the collection Kritiacht Theorie by Max Horkheimer, vols. I and II, * 1968 by S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main. English translation copyright * 1972 by Herder and Herder, Inc., for all essays except "Art and Mass Culture" and MThe Social Function of Philosophy,** which originally appeared in English in Studies in Philosophy and Social Science. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechan ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of The Continuum Publishing Corporation. Printed in the United States of America library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Horkheimer, Max, 1895-1973. Critical theory. Translation of: Kritische Theorie. "Essays from the Zeitschrift fur Soaalforschung"—Pref. Reprint. Originally published: New York: Seabury Press, [1972] Includes bibliographical references. Contents: Introduction by Stanley Aronowitz—Notes on science and the crisis—Materialism and metaphysics— [etc.] 1. Philosophy—Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Title. B3279.H8472E5 1982 193 81-22226 ISBN 0-8264-0083-3 (pbk.) AACR2 (previously ISBN 0-8164-9272-7) TRADITIONAL AND CRITICAL THEORY WHAT is "theory"? The question seems a rather easy one ior contemporary science. Theory for most researchers is the sum- total of propositions about a subject, the propositions being so linked with each other that a few are basic and the rest derive from these. -

Thesis Ecological Libertarianism

THESIS ECOLOGICAL LIBERTARIANISM: THE CASE FOR NONHUMAN SELF-OWNERSHIP Submitted by Zachary Nelson Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2016 Master’s Committee: Advisor: David McIvor Sandra Davis Lynn Hempel Copyright by Zachary Tyler Nelson 2016 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ECOLOGICAL LIBERTARIANISM: THE CASE FOR NONHUMAN SELF-OWNERSHIP The field of environmental political theory has made great gains in its relatively short existence as an academic discipline. One area in which these advancements can be noticed is the strong discussion surrounding the foundations, institutions, and processes of Western liberalism and the relationship of these elements to issues of environmentalism. Within this discussion has manifested the bedrock assumption that the underlying components of classical liberalism – namely individualism, negative liberties, and instrumental rationality – preclude or greatly hinder progress toward securing collective environmental needs. This assumption has great intuitive strength as well as exhibition in liberal democracies such as the United States. However, in using this assumption as a launchpad for reconsidering elements of liberalism, scholars have inadvertently closed alternate routes of analysis and theorization. This thesis aims to explore one such alternate route. Libertarianism, the contemporary reincarnation of classical liberalism, has been generally disregarded in policy and academic realms due to its stringent and inflexible adherence to self- interest, instrumental rationality, and individualism; in discussions of environment, these complaints are only augmented. These criticisms have been validated by a libertarian scholarship that emphasized nature as a warehouse of resources specifically suited for human use. -

Joseph C. Berendzen

JOSEPH C. BERENDZEN Department of Philosophy Loyola University, New Orleans Bobet Hall, Room 419 Office: 504.865.2828 Home: 504.894.8791 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D.: Villanova University, Philosophy, 2002 (Dissertation title: Toward an Existential Critical Theory of Deliberative Democracy, Director: Thomas W. Busch) M.A.: Villanova University, Philosophy, 1999 B.A.: Saint Louis University, summa cum laude, Philosophy & History, 1997 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Loyola University New Orleans, August 2010- Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Loyola University New Orleans, August 2004-July 2010. Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Villanova University, Academic Year 2003-2004. PUBLICATIONS Peer Reviewed Articles “Suffering and Theory: Max Horkheimer’s Early Essays and Contemporary Moral Philosophy,” Philosophy and Social Criticism, forthcoming. "Max Horkheimer", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2009 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2009/ entries horkheimer/>. “Coping with Nonconceptualism?: On Merleau-Ponty and McDowell,” Philosophy Today 53:2 (2009), 161-172. “Postmetaphysical Thinking or Refusal of Thought?: Max Horkheimer’s Materialism as Philosophical Stance,” International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 16:5 (2008), 695-718. “Institutional Design and Public Space: Hegel, Architecture, and Democracy,” Journal of Social Philosophy, 39:2 (2008), 291-307. “Sartre and the Communicative Paradigm in