Invasive Plants and the Green Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Oriental Bittersweet

Oriental Bittersweet Department of Environmental Protection Environmental and Geographic Information Center 79 Elm St., Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 424-3540 Invasive Plant Information Sheet Asiatic Bittersweet, Oriental Bittersweet Celastrus orbiculatus Staff Tree Family (Celastraceae) Ecological Impact: Asiatic bittersweet is a rapidly spreading deciduous vine that threatens all vegetation in open and forested areas. It overtops other species and forms dense stands that shade out native vegetation. Trees and shrubs can be strangled by twining stems that twist around and eventually constrict the flow of plant fluids. Trees can be girdled and weighed down by vines in the canopies, making them more susceptible to damage by wind, snow, and ice storms. There is evidence that Asiatic bittersweet can hybridize with American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens), which occurs in similar habitats. Hybridization will destroy the genetic integrity of the native species. Control Methods: The most effective control method for Asiatic Bittersweet is to prevent establishment by annually monitoring for and removing small plants. Eradication of established plants is difficult due to the persistent seed bank in the soil. Larger plants are best controlled by cutting combined with herbicide treatment. Mechanical Control: Light infestations of a few small plants can be controlled by mowing or cutting vines and hand pulling roots. Weekly mowing can eradicate plants, but less frequent mowing ( 2-3 times per year) will only stimulate root suckering. Cutting and uprooting plants is best done before fruiting. Vines with fruits should be bagged and disposed of in the trash to prevent seed dispersal. Heavy infestations can be controlled by cutting vines and immediately treating cut stems with herbicide. -

Oriental Bittersweet Orientalcelastrus Bittersweet Orbiculatus Controlcontrol Guidelinesguidelines

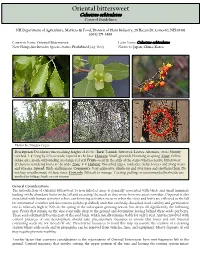

Oriental bittersweet OrientalCelastrus bittersweet orbiculatus ControlControl GuidelinesGuidelines NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Oriental Bittersweet Latin Name: Celastrus orbiculatus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan, China, Korea Photos by: Douglas Cygan Description: Deciduous vine reaching heights of 40-60'. Bark: Tannish, furrowed. Leaves: Alternate, ovate, bluntly toothed, 3-4'' long by 2/3’s as wide, tapered at the base. Flowers: Small, greenish, blooming in spring. Fruit: Yellow dehiscent capsule surrounding an orange-red aril. Fruits occur in the axils of the stems whereas native bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) fruits at the ends. Zone: 4-8. Habitat: Disturbed edges, roadsides, fields, forests and along rivers and streams. Spread: Birds and humans. Comments: Very aggressive, climbs up and over trees and smothers them. Do not buy wreaths made of these vines. Controls: Difficult to manage. Cutting, pulling, or recommended herbicide use applied to foliage, bark, or cut-stump. General Considerations The introduction of Oriental bittersweet to non infested areas is generally associated with birds and small mammals feeding on the abundant fruits in the fall and excreting the seeds as they move from one area to another. Dispersal is also associated with human activities where earth moving activities occur or when the vines and fruits are collected in the fall for ornamental wreathes and decorations (which is prohibited) and then carelessly discarded. Seed viability and germination rate is relatively high at 90% in the spring of the subsequent growing season, but drops off significantly the following year. -

Emerging Invasion Threat of the Liana Celastrus Orbiculatus

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 56: 1–25 (2020)Emerging invasion threat of the liana Celastrus orbiculatus in Europe 1 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.56.34261 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions Emerging invasion threat of the liana Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae) in Europe Zigmantas Gudžinskas1, Lukas Petrulaitis1, Egidijus Žalneravičius1 1 Nature Research Centre, Institute of Botany, Žaliųjų Ežerų Str. 49, Vilnius LT-12200, Lithuania Corresponding author: Zigmantas Gudžinskas ([email protected]) Academic editor: Franz Essl | Received 4 March 2019 | Accepted 12 March 2020 | Published 10 April 2020 Citation: Gudžinskas Z, Petrulaitis L, Žalneravičius E (2020) Emerging invasion threat of the liana Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae) in Europe. NeoBiota 56: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.56.34261 Abstract The woody vine Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae), Oriental bittersweet, is an alien species that recently has been found to be spreading in Europe. Many aspects of its biology and ecology are still obscure. This study evaluates the distribution and habitats, as well as size and age of stands of C. orbiculatus in Lithuania. We investigated whether meteorological factors affect radial stem increments and determined seedling recruit- ment in order to judge the plant’s potential for further spread in Europe. We studied the flower gender of C. orbiculatus in four populations in Lithuania and found that all sampled individuals were monoecious, although with dominant either functionally female or male flowers. Dendrochronological methods enabled us to reveal the approximate time of the first establishment of populations of C. orbiculatus in Lithuania. -

Effects of Japanese Barberry (Ranunculales: Berberidaceae)

Effects of Japanese Barberry (Ranunculales: Berberidaceae) Removal and Resulting Microclimatic Changes on Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) Abundances in Connecticut, USA Author(s): Scott C. Williams and Jeffrey S. Ward Source: Environmental Entomology, 39(6):1911-1921. 2010. Published By: Entomological Society of America DOI: 10.1603/EN10131 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1603/EN10131 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. PLANT-INSECT INTERACTIONS Effects of Japanese Barberry (Ranunculales: Berberidaceae) Removal and Resulting Microclimatic Changes on Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) Abundances in Connecticut, USA 1 SCOTT C. WILLIAMS AND JEFFREY S. WARD The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, Department of Forestry and Horticulture, PO Box 1106, New Haven, CT 06504 Environ. Entomol. 39(6): 1911Ð1921 (2010); DOI: 10.1603/EN10131 ABSTRACT Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii de Candolle) is a thorny, perennial, exotic, invasive shrub that is well established throughout much of the eastern United States. -

Celastrus Orbiculatus Thunb.) Biology, Ecology, and Impacts in New Zealand

Climbing spindle berry (Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb.) biology, ecology, and impacts in New Zealand SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 234 Peter A. Williams and Susan M. Timmins Published by Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in the DOC Science Publishing catalogue on the website, refer http://www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science and Research. © Copyright November 2003, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 0–478–22519–9 In the interest of forest conservation, DOC Science Publishing supports paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit; editing by Helen O’Leary and layout by Ruth Munro. Publication was approved by the Manager, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. Objectives 6 3. Methods 7 4. Results and Discussion 7 4.1 Taxonomy and description 7 4.2 History and distribution 9 4.3 Habitat 11 4.4 Morphology and growth 13 4.5 Physiology 14 4.6 Phenology and reproduction 15 4.7 Population dynamics 16 4.8 Ecological impacts 17 4.9 Weed management 18 5. Conclusions 23 6. Acknowledgements 23 7. -

Bittersweet (Celastrus Scandens & Celastrus Orbiculatus)

NYFA Quarterly Newsletter Winter 2017 Page 5 of 24 bank, waiting to be examined and have its genetic For my first field season, I primarily used the secrets unlocked. research award provided to me by NYFA for This year, ash seed production was scarce and traveling to my various research sites; from Akron spotty. Instead of sitting idle, we set out to collect and Basom in Genesee County to the Finger Lakes some of the species common to ash dominant forests. National Forest and additional Ithaca-based sites in Presumably, once EAB decimates our ash forests Schuyler and Tompkins County. So far, I have here in New York, we can expect understory species analyzed four communities that support American to suffer too, particularly in areas swarming with bittersweet populations, and hope to document plant other invasives like Japanese barberry and stiltgrass. communities at four more sites next summer. With We taught identification of 10 different native plants this information, I am hoping to determine a to our volunteer collectors and took in seeds from disturbance threshold for the species, and compare Mimulus ringens, Schizachyrium scoparium, Rhus it with sites inundated with Oriental bittersweet. copallinum, and others. These collections will live in American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) has a Colorado at the National Seeds of Success seed bank. NYS CoC (Coefficient of Conservatism) rating of 6 This program is part of a larger plan to develop a (see Rich Ring’s article in the Spring 2016 network of seed collectors: people who care about newsletter for an explanation on CoC values). This our native plants and want to do their part to help means the species generally has a narrow range of conserve them. -

Minnesota's Top 124 Terrestrial Invasive Plants and Pests

Photo by RichardhdWebbWebb 0LQQHVRWD V7RS 7HUUHVWULDO,QYDVLYH 3ODQWVDQG3HVWV 3ULRULWLHVIRU5HVHDUFK Sciencebased solutions to protect Minnesota’s prairies, forests, wetlands, and agricultural resources Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Prioritization Panel members ....................................................................................................... 4 III. Seventeen criteria, and their relative importance, to assess the threat a terrestrial invasive species poses to Minnesota ...................................................................................................................... 5 IV. Prioritized list of terrestrial invasive insects ................................................................................. 6 V. Prioritized list of terrestrial invasive plant pathogens .................................................................. 7 VI. Prioritized list of plants (weeds) ................................................................................................... 8 VII. Terrestrial invasive insects (alphabetically by common name): criteria ratings to determine threat to Minnesota. .................................................................................................................................... 9 VIII. Terrestrial invasive pathogens (alphabetically by disease among bacteria, fungi, nematodes, oomycetes, parasitic plants, and viruses): criteria ratings -

Berberis Thunbergii1

Fact Sheet FPS-66 October, 1999 Berberis thunbergii1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction Japanese Barberry is thorny, so it’s useful for barrier plantings (Fig. 1). The plant tolerates most light exposures and soils, but purple-leaved cultivars turn green in shade. This shrub grows slowly but transplants easily. It grows three to six feet tall and spreads four to seven feet. Japanese Barberry can be sheared and used as a hedge plant. The main ornamental features are persistent red fruits and fall color in shades of red, orange and yellow. Some strains fruit more heavily than others. The plant produces yellow flowers, but these are not highly ornamental. General Information Scientific name: Berberis thunbergii Pronunciation: BUR-bur-iss thun-BUR-jee-eye Common name(s): Japanese Barberry Family: Berberidaceae Plant type: ground cover; shrub USDA hardiness zones: 4 through 9 (Fig. 2) Planting month for zone 7: year round Figure 1. Japanese Barberry. Planting month for zone 8: year round Planting month for zone 9: year round Origin: not native to North America Uses: border; mass planting; ground cover; hedge; edging; Description small parking lot islands (< 100 square feet in size); medium- Height: 2 to 8 feet sized parking lot islands (100-200 square feet in size); large Spread: 4 to 6 feet parking lot islands (> 200 square feet in size) Plant habit: round Availablity: generally available in many areas within its Plant density: dense hardiness range Growth rate: moderate Texture: fine 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-66, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Oriental Bittersweet Celastrus Orbiculatus Thunb

Oriental bittersweet Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb. Staff-tree Family (Celastraceae) DESCRIPTION Oriental bittersweet is a woody, deciduous vine that twines around and drapes itself over other trees and shrubs in successional fields and along forest edges, often completely covering the supporting vegetation. In the shade it grows less vigorously, sometimes forming small trailing shrubs. Oriental bittersweet is very similar to the native American bittersweet (C. scandens). The female flowers and fruits of oriental bittersweet are located in the leaf axils along the stem; American bittersweet, in contrast, blooms at the tips of the stems. The two species cannot reliably be distinguished in the absence of Oriental bittersweet female flowers or fruits. Although American bittersweet has generally narrower leaves, this difference is not reliable. Height - Bittersweet climbs to heights of 50 feet or more when large trees are available to provide support. Stem - The twining stems may reach a diameter of 4 inches, they often deform and eventually girdle the trunks or branches of trees around which they have grown. Leaves - Mature leaves of oriental bittersweet are usually broadly rounded to nearly orbicular; however on young shoots they can be much more narrow, leading to confusion with the native species. The leaves are arranged alternately on the stem, and are deciduous; they turn yellow in the fall. American bittersweet Flowers - Bittersweet flowers, which appear in May or June, are small and greenish. In general male and female flowers are produced on separate plants, however sometimes a few perfect flowers are also present. Fruit and seed - The fruits are yellow or orange capsules that open to reveal 3 or 4 bright red seeds with their fleshy arils. -

ABSTRACT ROUNSAVILLE, TODD JEFFREY. Cytogenetics

ABSTRACT ROUNSAVILLE, TODD JEFFREY. Cytogenetics, Micropropagation, and Reproductive Biology of Berberis, Mahonia, and Miscanthus. (Under the direction of Thomas G. Ranney). Research was conducted to determine the genome sizes and ploidy levels for a diverse collection of Berberis L. and Mahonia Nutt. genotypes, develop a micropropagation protocol for Mahonia „Soft Caress‟, and examine the fertility and reproductive pathways among clones of diploid and triploid Miscanthus sinensis Andersson. Berberis and Mahonia are sister taxa within the Berberidaceae with strong potential for ornamental improvement. Propidium iodide (PI) flow cytometric analysis was conducted to determine genome sizes. Mean 1CX genome size varied between the two Mahonia subgenera (Occidentales = 1.17 pg, Orientales = 1.27 pg), while those of Berberis subgenera were similar (Australes = 1.45 pg, Septentrionales = 1.47 pg), but larger than those of Mahonia. Traditional cytology was performed on representative species to calibrate genome sizes with ploidy levels. While the majority of species were determined to be diploid with 2n = 2x = 28, artificially-induced autopolyploid Berberis thunbergii seedlings were confirmed to be tetraploid and an accession of Mahonia nervosa was confirmed to be hexaploid. Genome sizes and ploidy levels are presented for the first time for the majority of taxa sampled and will serve as a resource for plant breeders, ecologists, and systematists. Mahonia „Soft Caress‟ is a unique new cultivar exhibiting a compact form and delicate evergreen leaves, though propagation can be a limiting factor for production. Micropropagation protocols for M. „Soft Caress‟ were developed to expedite multiplication and serve as a foundation for future work with other Mahonia taxa. -

American and Oriental Bittersweet Identification

American and Oriental Bittersweet Identification nvasive species are one of the greatest threats to native ecosystems. They I can crowd out native species and change the natural nutrient cycling processes that take place in ecosystems. Oriental bittersweet One of the best ways to combat invasive which plants to target for control. Using female plants have this character available species is by identifying small infestations fruit and leaf characters, the two species can for identification. In terms of flowers, only and removing them. be discriminated from each other. mature male and female plants have these However, certain traits are more reliable for present, and only for a brief time of the year One invader threatening midwestern correct identification than others. during the spring. ecosystems is oriental bittersweet Classically, the position of the fruit and (Celastrus orbiculatus). This woody vine Vegetative traits apply to plants regardless flowers on the stems has been cited as the was introduced to the eastern United States of their sex or maturity. The most most definitive means of discriminating in the mid-1800s. It has spread from the definitive vegetative trait is the posture of between the species. east to the south and west and is now the leaves at leaf out of the first buds in the moving into midwestern natural areas. Oriental bittersweet has fruit and flowers spring. The leaves of oriental bittersweet Oriental bittersweet can be found in a located in the leaf axils along the length of are conduplicate (two sides of the leaf variety of habitats, from roadsides to the stem. American bittersweet, however, folded against each other) and tightly interior forests and sand dunes.