Access to the Internet: Regulation Or Markets?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control Nicholas J

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 2 2006 A Second Amendment Moment: The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control Nicholas J. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Nicholas J. Johnson, A Second Amendment Moment: The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2005). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. A Second Amendment Moment THE CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS OF GUN CONTROL Nicholas J. Johnson† I. INTRODUCTION A. Constitutional Politics Bruce Ackerman’s claim that America’s endorsement of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies actually changed the United States Constitution to affirm an activist regulatory state, advances the idea that higher lawmaking on the same order as Article Five amendment can be attained through and discerned by attention to our “constitutional politics.”1 Ackerman’s “Dualist” model requires that we distinguish between two types of politics.2 In normal politics, organized interest groups try to influence democratically elected representatives while regular citizens get on with life.3 In constitutional politics, the mass of citizens are energized to engage and debate matters of fundamental principle.4 Our history is dominated by normal politics. But our tradition places a higher value on mobilized efforts to gain the consent of † Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law, J.D. Harvard Law School, 1984, B.S.B.A. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. Defense Travel System (DTS) – #4373 2. DOD Travel Payments Improper Payment Measure – #4372 3. Follow up Amendment 4. DOD Earmarks Cost and Grading Amendment – #4370 5. Limitation on DoD Contract Performance Bonuses – #4371 1. Amendment # 4373 – No Federal funds for the future development and operation of the Defense Travel System Background The Defense Travel System (DTS) is an end-to-end electronic travel system intended to integrate all travel functions, from authorization through ticket purchase to accounting for the Department of Defense. The system was initiated in 1998 and it was supposed to be fully deployed by 2002. DTS is currently in the final phase of a six-year contract that expires September 30, 2006. In its entire history, the system has never met a deadline, never stayed within cost estimates, and never performed adequately. To date, DTS has cost the taxpayers $474 million – more than $200 million more than it was originally projected to cost. It is still not fully deployed. It is grossly underutilized. And tests have repeatedly shown that it does not consistently find the lowest applicable airfare – so even where it is deployed and used, it does not really achieve the savings proposed. This amendment prohibits continued funding of DTS and instead requires DOD to shift to a fixed price per transaction e-travel system used by government agencies in the civilian sector, as set up under General Services Administration (GSA) contracts. Quotes of Senators from last year’s debate • Senator Allen stated during the debate last year that “as a practical matter we would like to have another year or so to see (DTS) fully implemented.” • Senator Coleman stated during the debate, “… if we cannot get the right answers we should pull the plug, but now is not the time to pull the plug. -

12Th Grade Curriculum

THE TOM BRADLEY PROJECT STANDARDS: 12.6.6 Evaluate the rolls of polls, campaign advertising, and controversies over campaign funding. 12.6.6 Analyze trends in voter turnout. COMMON CORE STATE KEY TERMS AND ESSAY QUESTION STANDARDS CONTENT Reading Standards for Literacy in elections History/Social Studies 6-12 How did the election of Tom shared power Bradley in 1973 reflect the local responsibilities and Writing Standard for Literacy in building of racial coalitions in authority History/Social Studies 6-12 voting patterns in the 1970s and Text Types and Purpose the advancement of minority 2. Write informative/explanatory texts, opportunities? including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/experiments, or technical processes. B. Develop the topic with relevant, well-chosen facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and expamples LESSON OVERVIEW MATERIALS Doc. A LA Times on Voter turnout, May 15, 2003 Day 1 View Module 2 of Tom Bradley video. Doc. B Voter turnout spreadsheet May 15, 2003 (edited) Read Tom Bradley biography. Doc. C Statistics May 15,2003 Day 2 Doc. D Tom Bradley biography Analyze issues related to voter turnout in Doc. E Census, 2000 2013 Los Angeles Mayoral Election and Doc, F1973 Mayoral election connections to the 1973 campaign for Doc .G Interview 1973 Mayor. Doc. H Election Night speech 1989 Day 3 Doc I LA Times Bradley’s first year 1974 Analyze issues in 1973 campaign. Doc. J LA Times Campaign issues 1973 Analyze building of racial coalitions Doc K LA Times articles 1973 among voters. Day 4 Doc. L LA Times campaign issues 1973 Write essay. -

MOST BUSINESS-FRIENDLY in This Issue: City National Bank and Toyota Receive 2006 Eddy Awards • 2006 Eddy Awards Coverage & Photos

EL SEGUNDO: MOST BUSINESS-FRIENDLY In This Issue: City National Bank and Toyota receive 2006 Eddy Awards • 2006 Eddy Awards Coverage & Photos • Change in LAEDC Governance • Business Assistance Mid-Year Report • International Update • Transportation Update For full coverage and photo highlights, turn to page 6 C-17 PRODUCTION LINE CONTINUES Region’s Red Team enlisted support from Governor, US President Take a Look Into On September 29, President this national asset and proven Congress and President Bush to George W. Bush signed a workhorse for military and save the thousands of jobs at the THE FUTURE Defense Appropriations Bill, humanitarian missions. manufacturing plant in Long of Our Economy allowing $4.4 billion in funding Beach by continuing to fund the for the C-17 program. The bill The Red Team hopes to capital- C-17 program. saves 5,500 direct jobs at the ize on the effort's momentum to Boeing plant in Long Beach extend the life of the C-17 pro- Addressing the Boeing employ- 2007-2008 through the end of 2009. duction line even further. With ees, the Governor said, “We have 64 more planes, the production all been fighting for this for years. ECONOMIC The fight to save the C-17 pro- line could be extended until We have been working overtime duction line has indeed been a 2011. to keep all of you working...I FORECAST tough road since 2005, making joined with other governors to the signing of the bill a real victo- In March, the Australian govern- push for continued production of ry for the C-17 Program Red ment placed an order for four C- the incredible aircraft. -

Governing Urban School Districts: Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Education View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Governing Urban School Districts Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect Change Catherine H. Augustine, Diana Epstein, Mirka Vuollo The research described in this report was conducted within RAND Education for the Presidents' Joint Commission on LAUSD Governance. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Light snow or rain, 38°F (30C) Tonight: Clear, cold, 24°F (-40C) ewspaper Tomorrow: Mostly sunny, 38°F (4°C) Details, Page 2 NUDlber 11 Cambridge, The day, March 11, 199 Corporation Passes 5% Tuition mcrease Student self-help levels remain constant By Z3reena Hussain is the steady decrease in federal ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR funding, Williams said. The Executive Committee of the "I continually worry about the MIT Corporation approved a 5 per- cost of education, but I am pleased cent tuition hike for the] 997-98 that we have kept the growth of the academic year, President Vest student budget (tuition, room and announced at Friday's Corporation board) to within about one and a meeting. half percent of the [Consumer Price This amounts to an increase of Index] for the last three years," Vest $1,100 to a tuition level of $23,] 00. said. Including a projected increase in the The Consumer Price Index is a cost of room and board by 3.1 per- standard benchmark used to calcu- cent, the total cost for an MIT edu- late inflation. cation during the coming year will "The cost of education increases be about $29,650. and does so faster than the While the costs of tuition and Consumer Price Index. MIT's edu- room and board increased, the stu- cationa] programs are both labor dent self-help level will remain the and capital intensive, and tuition is same at $8,600. Self-help includes a major source of unrestricted ~he base amount expected of stu- dents to contribute toward financing Tuition, Page II their education before receiving scholarship assistance, and it includes MIT term-time work, loans, and savings. -

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor Since 1978

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor since 1978 California Fair Political Practices Commission • September 2010 Breaking the Bank a report by the California Fair Political Practices Commission September 2010 California Fair Political Practices Commission 428 J Street, Suite 620 Sacramento, CA 95814 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Cost-per-Vote Chart 8 Primary Election Comparisons 10 1978 Gubernatorial Primary Election 11 1982 Gubernatorial Primary Election 13 1986 Gubernatorial Primary Election 15 1990 Gubernatorial Primary Election 16 1994 Gubernatorial Primary Election 18 1998 Gubernatorial Primary Election 20 2002 Gubernatorial Primary Election 22 2006 Gubernatorial Primary Election 24 2010 Gubernatorial Primary Election 26 Methodology 28 Appendix 29 Executive Summary s candidates prepare for the traditional general election campaign kickoff, it is clear Athat the 2010 campaign will shatter all previous records for political spending. While it is not possible to predict how much money will be spent between now and November 2, it may be useful to compare the levels of spending in this year’s primary campaign with that of previous election cycles. In this report, “Breaking the Bank,” staff of the Fair Political Practices Commission determined the spending of each candidate in every California gubernatorial primary since 1978 and calculated the actual spending per vote cast—in 2010 dollars—as candidates sought their party’s nomination. The conclusion: over time, gubernatorial primary elections have become more costly and fewer people turnout at the polls. But that only scratches the surface of what has happened since 19781. Other highlights of the report include: Since 1998, the rise of the self-funded candidate has dramatically increased the cost of running for governor in California. -

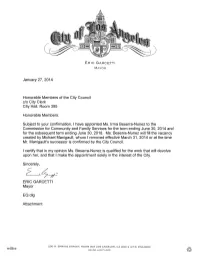

Subject to Your Confirmation, I Have Appointed Ms

ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR January 27, 2014 Honorable Members of the City Council c/o City Clerk City Hall, Room 395 Honorable Members: Subject to your confirmation, I have appointed Ms. Irma Beserra-Nunez to the Commission for Community and Family Services for the term ending June 30, 2014 and for the subsequent term ending June 30, 2018. Ms. Beserra-Nunez will fill the vacancy created by Michael Manigault, whom I removed effective March 31,2014 or at the time Mr. Manigault's successor is confirmed by the City Council. I certify that in my opinion Ms. Beserra-Nunez is qualified for the work that will devolve upon her, and that I make the appointment solely in the interest of the City. Sincerely, L471~ ERIC GARCETTI Mayor EG:dlg Attachment 200 N. SPR!NG STREET, ROOM 303 LOS ANGELES, CA 90012 (213) 978-0600 MAYOR.LACITY.ORG COMMISSION APPOINTMENT FORM Name: Irma Beserra-Nunez Commission: Commission for Community and Family Services End of Term: 6/30/2014 Appointee Information 1. Race/ethnicity: Latina 2. Gender: Female 3. Council district and neighborhood of residence: 5 - SouthValley 4. Are you a registered voter? Yes 5. Prior commission experience: 6. Highest level of education completed: BA California State University Los Angeles 7. Occupation/profession: Advocate for Adult Education 8. Experience(s) that qualifies person for appointment: See attached resume 9. Purpose of this appointment: Replacement 10. Current composition of the commission (excluding appointee): ·,{Narnc{ 1< APCr .. liCD > Gender •.A.r>btdate Te"';~nd~ AI-Mansour, Chancela East LA 14 African American F 25-Seo-12 30-Jun-16 Castillo, Carolina East LA 14 Latina F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 Chan, Yvonne North Valley 12 Asian Pacific Islander F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-14 Duardo, Debra East LA 14 Latina F 22-Jun-11 30-Jun-14 Garcia, Marv South Valley 2 Latina F 08-0ct-10 30-Jun-16 Hill, PeQQY Central 4 African American F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 lqlehart, Alfreda Central 10 African American F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 Lara, Alicia Central 4 Latina F 28-Seo-10 30-Jun-14 Little, Marc T. -

Gun Laws in the USA

Gun Laws in the USA PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 08 May 2013 00:46:08 UTC Contents Articles Gun law in the United States 1 Gun laws in the United States by state 7 .50 Caliber BMG Regulation Act of 2004 43 AB 1471 45 AB 2062 46 An Act Concerning Gun Violence Prevention and Children's Safety 47 Concealed carry in the United States 49 Constitutional Carry 65 District of Columbia v. Heller 71 Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 86 FOID (firearms) 86 McDonald v. Chicago 88 Missouri Proposition B (1999) 93 Montana Firearms Freedom Act 97 Mulford Act 99 Nunn v. Georgia 100 NY SAFE Act 103 Open carry in the United States 107 Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act of 1989 113 San Francisco Proposition H (2005) 117 Shannon's law (Arizona) 120 Students for Concealed Carry 122 Sullivan Act 124 Transport Assumption 126 Uniform Firearms Act 128 Uniform Machine Gun Act 133 Unintended Consequences (novel) 133 United States v. Olofson 137 Woollard v. Sheridan 139 References Article Sources and Contributors 142 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 145 Article Licenses License 146 Gun law in the United States 1 Gun law in the United States U.S. Firearms Legal Topics • Assault weapon • ATF Bureau • Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act • Concealed carry in the U.S. • Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban • Federal Assault Weapons Ban • Federal Firearms License • Firearm case law • Firearm Owners Protection Act • Gun Control Act of 1968 • Gun laws in the U.S.—by state • Gun laws in the U.S.—federal • Gun politics in the U.S. -

Sustainable California Ucla Luskin School of Public Affairs Part 2: Water Editor’S Ote

ISSUE #4 / FALL 2016 DESIGNS FOR A NEW CALIFORNIA IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUSTAINABLE CALIFORNIA UCLA LUSKIN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS PART 2: WATER EDITOR’S OTE BLUEPRINT A magazine of research, policy, Los Angeles and California THIS ISSUE OF BLUEPRINT IS SEVERAL THINGS AT ONCE: It’s Part 2 of our The theft, fair or not, also established Los Angeles as a city dependent sustainability series, following up on the spring look at power with a fall take upon imports. For most of our history, water has come from the Sierras (and on water. It’s also an opportunity to examine two of Los Angeles’ most im- from the Colorado River and Sacramento Bay Delta), while power has been portant political figures — the city’s mayor and council president. Finally, it’s generated by coal plants in Utah and Arizona. As Mayor Eric Garcetti notes a look at how power works, and doesn’t work, in Los Angeles — whether in this issue, the city has long been in the strange position of flushing out it’s the region’s infamous fragmentation and the problems that creates in rain that falls here while importing water from far away. water prices or the subtleties of political leadership in and around city hall. That’s changing. As these stories and interviews remind us, Los Angeles is a complicat- Guided in part by research featured in this issue, as well as directives ed place to solve big problems, and none is bigger than L.A.’s historic from the mayor, Los Angeles is committing itself to a water future very quest for water. -

57Th Socal Journalism Awards

FIFTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL5 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA7 JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th 57 ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 48 NOMINATIONS JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB 57TH SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS WELCOME Dear Friends of L.A. Press Club, Well, you’ve done it this time. Yes, you really have! The Los Angeles Press Club’s 57th annual Southern California Journalism Awards are marked by a jaw-dropping, record-breaking number of submissions. They kept our sister Press Clubs across the country, who judge our annual competition, very busy and, no doubt, very impressed. So, as we welcome you this evening, know that even to arrive as a finalist is quite an accomplishment. Tonight in this very Biltmore ballroom, where Senator (and future President) John F. Kennedy held his first news conference after securing his party’s nomination, we honor the contributions of our colleagues. Some are no longer with Robert Kovacik us and we will dedicate this ceremony to three of the best among them: Al Martinez, Rick Orlov and Stan Chambers. The Los Angeles Press Club is where journalists and student journalists, working on all platforms, share their ideas and their concerns in our ever changing industry. If you are not a member, we invite you to join the oldest organization of its kind in Southern California. On behalf of our Board, we hope you have an opportunity this evening to reconnect with colleagues or to make some new connections. Together we will recognize our esteemed honorees: Willow Bay, Shane Smith and Vice News, the “CBS This Morning” team and representatives from Charlie Hebdo. -

William Brucher Dissertation Complete 5-13-12

ON THE EDGE OF THE PACIFIC RIM: CAPITALISM AND WORK ON THE LOS ANGELES WATERFRONT BY WILLIAM C. BRUCHER B.A., BATES COLLEGE, 2002 A.M., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2007 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2012 © Copyright 2012 by William C. Brucher This dissertation by William C. Brucher is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _______________ ________________________________ Elliott J. Gorn, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _______________ ________________________________ Seth E. Rockman, Reader Date _______________ ________________________________ Robert O. Self, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _______________ ________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae William C. Brucher was born on March 11, 1980, in Bangor, Maine and grew up in the nearby town of Bradford. He graduated with a B.A. in history from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine in 2002. From July 2002 through August 2006, he worked as a union organizer in the healthcare and human service industries for the Service Employees International Union and the Maine State Employees Association. He entered the Ph.D. program in history at Brown University in September 2006, earned his master’s degree in May 2007, and passed his qualifying exams in December 2008. While at Brown, he studied modern U.S. social and cultural history, transnational labor history, and modern Latin American history. He has served as a teaching assistant in a wide variety of early and modern U.S.