An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works for Tuba Published By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Gustavo Dudamel 2020/21 Season (Long Biography)

GUSTAVO DUDAMEL 2020/21 SEASON (LONG BIOGRAPHY) Gustavo Dudamel is driven by the belief that music has the power to transform lives, to inspire, and to change the world. Through his dynamic presence on the podium and his tireless advocacy for arts education, Dudamel has introduced classical music to new audiences around the world and has helped to provide access to the arts for countless people in underserved communities. As the Music & Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, now in his twelfth season, Dudamel’s bold programming and expansive vision led The New York Times to herald the LA Phil as “the most important orchestra in America – period.” With the COVID-19 global pandemic shutting down the majority of live performances, Dudamel has committed even more time and energy to his mission of bringing music to young people across the globe, firm in his belief that the arts play an essential role in creating a more just, peaceful, and integrated society. While quarantining in Los Angeles, he hosted a new radio program from his living room entitled “At Home with Gustavo,” sharing personal stories and musical selections as a way to bring people together during a time of isolation. The program was broadcast locally as well as internationally in both English and Spanish, with guest co-hosts including, among others, composer John Williams, his wife, actress María Valverde. Dudamel also participated in Global Citizen’s Global Goal: Unite For Our Future TV fundraising special, giving a socially-distanced performance from the Hollywood Bowl with the LA Phil and YOLA (Youth Orchestra Los Angeles). -

SCI Newsletter XXXVI:2

2005 SCI Region V Conference An Interview with Steven Stucky Christopher Gable Ralph S. Kendrick Butler University RSK: Congratulations on winning the Indianapolis, Indiana Pulitzer Prize this year! How does one feel UPCOMING November 11–13 after winning such a distinguished award? co-hosted by Were you surprised by it, and has your life CONFERENCES Frank Felice and Michael Schelle been much different since? 2006 Region VII Conference During the second weekend of November, SS: I can’t pretend that I’m not pleased University of New Mexico 2005, approximately 48 composers from that this year my number came up. It’s not In conjunction with the John Donald all across the country converged on the that I think that objectively my piece was Robb Composers Symposium campus of Butler University for the SCI the “best” one, of course, but a committee April 2–5, 2006 Midwest Chapter (Region V) Conference. of respected peers found the piece worth Host: Christopher Shultis After nine full-length concerts in three discussing in the company of some of the E-mail: [email protected] days, we were all exhausted, but thrilled by other terrific pieces American composers the experience and warmed by the gave us over the past year. That’s enough 2006 National Conference generosity of the conference’s co-hosts, to encourage a composer to think he San Antonio, TX Frank Felice and Michael Schelle. There hasn’t been wasting his time, and to September 13-17, 2006 was networking, socializing, rehearsing, inspire him to keep trying to do his best. -

Transfer Learning for Piano Sustain-Pedal Detection

Transfer Learning for Piano Sustain-Pedal Detection Beici Liang, Gyorgy¨ Fazekas and Mark Sandler Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London London, United Kingdom Email: fbeici.liang,g.fazekas,[email protected] Abstract—Detecting piano pedalling techniques in polyphonic music remains a challenging task in music information retrieval. While other piano-related tasks, such as pitch estimation and onset detection, have seen improvement through applying deep learning methods, little work has been done to develop deep learning models to detect playing techniques. In this paper, we propose a transfer learning approach for the detection of sustain- pedal techniques, which are commonly used by pianists to enrich the sound. In the source task, a convolutional neural network (CNN) is trained for learning spectral and temporal contexts when the sustain pedal is pressed using a large dataset generated by a physical modelling virtual instrument. The CNN is designed Melspectrogram and experimented through exploiting the knowledge of piano acoustics and physics. This can achieve an accuracy score of MIDI & sensor 0 127 0.98 in the validation results. In the target task, the knowledge learned from the synthesised data can be transferred to detect the Fig. 1. Different representations of the same note played without (first note) or sustain pedal in acoustic piano recordings. A concatenated feature with (second note) the sustain pedal, including music score, melspectrogram vector using the activations of the trained convolutional layers is and messages from MIDI or sensor data. extracted from the recordings and classified into frame-wise pedal press or release. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in acoustic piano recordings of Chopin’s music. -

Pedagogical Practices Related to the Ability to Discern and Correct

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Pedagogical Practices Related to the Ability to Discern and Correct Intonation Errors: An Evaluation of Current Practices, Expectations, and a Model for Instruction Ryan Vincent Scherber Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC PEDAGOGICAL PRACTICES RELATED TO THE ABILITY TO DISCERN AND CORRECT INTONATION ERRORS: AN EVALUATION OF CURRENT PRACTICES, EXPECTATIONS, AND A MODEL FOR INSTRUCTION By RYAN VINCENT SCHERBER A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Ryan V. Scherber defended this dissertation on June 18, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: William Fredrickson Professor Directing Dissertation Alexander Jimenez University Representative John Geringer Committee Member Patrick Dunnigan Committee Member Clifford Madsen Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Mary Scherber, a selfless individual to whom I owe much. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this journey would not have been possible without the care and support of my family, mentors, colleagues, and friends. Your support and encouragement have proven invaluable throughout this process and I feel privileged to have earned your kindness and assistance. To Dr. William Fredrickson, I extend my deepest and most sincere gratitude. You have been a remarkable inspiration during my time at FSU and I will be eternally thankful for the opportunity to have worked closely with you. -

By Aaron Jay Kernis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 “A Voice, A Messenger” by Aaron Jay Kernis: A Performer's Guide and Historical Analysis Pagean Marie DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Pagean Marie, "“A Voice, A Messenger” by Aaron Jay Kernis: A Performer's Guide and Historical Analysis" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3434. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3434 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “A VOICE, A MESSENGER” BY AARON JAY KERNIS: A PERFORMER’S GUIDE AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Pagean Marie DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my husband, Nicholas DiSalvio ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Joseph Skillen, Prof. Kristin Sosnowsky, and Dr. Brij Mohan, for their patience and guidance in completing this document. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brian Shaw for keeping me focused in the “present time” for the past three years. Thank you to those who gave me their time and allowed me to interview them for this project: Dr. -

Gr. 4 to 8 Study Guide

Toronto Symphony TS Orchestra Gr. 4 to 8 Study Guide Conductors for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra School Concerts are generously supported by Mrs. Gert Wharton. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s School Concerts are generously supported by The William Birchall Foundation and an anonymous donor. Click on top right of pages to return to the table of contents! Table of Contents Concert Overview Concert Preparation Program Notes 3 4 - 6 7 - 11 Lesson Plans Artist Biographies MusicalGlossary 12 - 38 39 - 42 43 - 44 Instruments in Musicians Teacher & Student the Orchestra of the TSO Evaluation Forms 45 - 56 57 - 58 59 - 60 The Toronto Symphony Orchestra gratefully acknowledges Pierre Rivard & Elizabeth Hanson for preparing the lesson plans included in this guide - 2 - Concert Overview No two performances will be the same Play It by Ear! in this laugh-out-loud interactive February 26-28, 2019 concert about improvisation! Featuring Second City alumni, and hosted by Suitable for grades 4–8 Kevin Frank, this delightfully funny show demonstrates improvisatory techniques Simon Rivard, Resident Conductor and includes performances of orchestral Kevin Frank, host works that were created through Second City Alumni, actors improvisation. Each concert promises to Talisa Blackman, piano be one of a kind! Co-production with the National Arts Centre Orchestra Program to include excerpts from*: • Mozart: Overture to The Marriage of Figaro • Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, Op. 35, Mvt. 2 (Excerpt) • Copland: Variations on a Shaker Melody • Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, Mvt. 4 (Excerpt) • Holst: St. Pauls Suite, Mvt. 4 *Program subject to change - 3 - Concert Preparation Let's Get Ready! Your class is coming to Roy Thomson Hall to see and hear the Toronto Symphony Orchestra! Here are some suggestions of what to do before, during, and after the performance. -

Xtl /Vo0 , 6 Z Se

xtl /Vo0 , 6 Z se PERCEPTION OF TIMBRAL DIFFERENCES AMONG BASS TUBAS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Gary Thomas Cattley, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1987 Cattley, Gary T., Perception of Timbral Differences among Bass Tubas. Master of Music (Music Education), August, 1987, 98 pp., 4 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 74 titles. The present study explored whether musicians could (1) differentiate among the timbres of bass tubas of a single design, but constructed of different materials, (2) determine differences within certain ranges and articulations, and (3) possess different perceptual abilities depending on previous experience in low brass performance. Findings indicated that (1) tubas made to the same specifications and constructed of the same material differed as much as those of made to the same specifications, constructed of different materials; 2) significant differences in perceptibility which occurred among tubas were inconsistent across ranges and articulations, and differed due to phrase type and the specific tuba on which the phrase was played; 3) low brass players did not differ from other auditors in their perception of timbral differences. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . - . - . v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . .*. ... .vi Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ............. Purpose of the Study Research Questions Definition Delimitations Chapter Bibliography II. REVIEW OF THE RELATED LITERATURE . 14 The Perception of Timbre Background Acoustical Attributes of Timbre Subjective Aspects of Timbre Subjective Measurement of Timbre Contextual Presentation of Stimuli The Influence of Materials on Timbre Chapter Bibliography III. METHODS AND PROCEDURES . -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

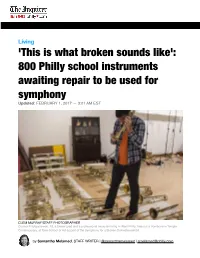

'This Is What Broken Sounds Like': 800 Philly School Instruments Awaiting Repair to Be Used for Symphony Updated: FEBRUARY 1, 2017 — 3:01 AM EST

Living 'This is what broken sounds like': 800 Philly school instruments awaiting repair to be used for symphony Updated: FEBRUARY 1, 2017 — 3:01 AM EST CLEM MURRAY/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER Connor Przybyszewski, 28, a Drexel grad and a professional musician living in West Philly, tries out a trombone in Temple Contemporary, at Tyler School of Art as part of the Symphony for a Broken Orchestra exhibit. by Samantha Melamed, STAFF WRITER | @samanthamelamed | [email protected] As a small corps of musicians arrived on a recent morning, Jeremy Thal gathered them into a loose huddle and laid out the day’s mission. “We know what one broken tuba sounds like,” he said. “Now, we’re kind of curious what four broken tubas sound like. So, everyone grab a horn that has a leak -- a sizable leak like this one, that’s missing a valve.” A half-hour later, a quartet was assembled: a French horn, 'This is what broken sounds like': approximately one-and-a-half trombones, and a French 800 Philly school instruments awaiting repair to be used for horn-meets- trumpet Frankenstein they were calling a symphony French hornet. “We’ll do two normal notes, and two notes of weirds,” Thal suggested. Then they played -- a sound that was a little bit Billie Holiday, a little bit pack of feral cats. This sonic strangeness is the result of a ragtag harvest from classrooms and storage spaces across the School District of Philadelphia, where a backlog of broken instruments has piled up since funding was slashed in 2013. Today, there are more than 800 of them out of a total instrument inventory of 10,000.