Waywayseecappo TK Study Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tri-Roads Forward Development Plan Prepared For: the Tri-Roads Planning District | Prepared By: Richard Wintrup July 2018

Tri-Roads Forward Development Plan Prepared for: The Tri-Roads Planning District | Prepared by: Richard Wintrup July 2018 By-Law No. 18/01/18 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Plan Purpose 1 1.2 Plan Approach 2 1.3 Plan Outline 5 2.0 Planning Intent 7 2.1 Vision 7 2.2 Guiding Principles 7 2.3 District-wide Goals and Objectives 9 3.0 Planning Area 11 3.1 Boundaries of the Planning Area 12 3.2 Surrounding the Planning Area 12 4.0 Planning Policies 15 4.1 Progressive Areas 15 4.1.1 Urban Policy Areas 17 4.1.1.1 Main Streets 20 4.1.2 Tourism Policy Areas 21 4.1.2.1 Cottage Uses 24 4.1.2.2 Dynamic Recreational Uses 25 4.1.3 Rural Residential Policy Areas 26 4.2 TransFormative Areas 29 4.2.1 Mineral Resources Policy Areas 31 4.2.2 Future Growth Areas 32 4.2.3 Watershed Growth Areas 34 4.3 Conservative Areas 35 4.3.1 Agricultural Policy Areas 37 4.3.1.1 Livestock Operation Uses 41 4.3.1.2 Hazardous Uses 44 4.3.2 Natural Lands Policy Areas 46 4.3.3 Water Body Policy Areas 48 4.3.4 Heritage Resource Uses 50 5.0 Planning InFrastructure 51 5.1 Transportation Policies 51 5.1.1 Roads 51 5.1.2 Road Hierarchy 52 5.1.3 Active Transportation 56 5.1.4 Airports 57 5.1.5 Rail Lines 57 5.2 Public Service Policies 59 5.2.1 Water and Wastewater 59 5.2.2 Solid Waste 60 5.2.3 Land Drainage 61 5.2.4 Utilities 62 5.2.5 Green and Open Spaces 62 6.0 Planning Area Background 65 6.1 Tri-Roads Background Study 65 6.2 Growth Scenarios 65 6.3 Growth Scenario Implications 66 6.4 Planning Process 67 6.5 Project Governance 68 7.0 Implementation 69 7.1 Implementation -

RIDING MOUNTAIN Ecosystem Community Atlas MAPS & Tables

riding mountain E c o s y s t e m Community Atlas © 2004 Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) CPAWS gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada's Voluntary Sector Initiative, through the Parks Canada Agency, and the in-kind support of ESRI Canada. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada. To view electronic versions of the four atlases produced in this project, please visit: <www.cpaws.org/community-atlas> For more information on the Riding Mountain atlas, contact: CPAWS Manitoba P.O. Box 344 Winnipeg, MB R3C 2H6 Tel: (204) 949-0782 / Email: [email protected] Cover photo credits: Ian Ward (Deep Lake, Riding Mountain National Park), Paul Pratt, UBC (barred owl), Parks Canada (black bear and field outside Riding Mountain boundary) Printed on 100% post consumer stock table of contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. i Section 5.0 WATER 5.1 Drainage ..........................................................................23 Ian Ward Section 1.0 RIDING MOUNTAIN GREATER ECOSYSTEM 5.2 Wetlands of the Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve ...........23 1.1 The Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve ............................. 1 The prairie pothole region .............................................24 Section 2.0 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY Stewardship and conservation of riparian areas .............25 2.1 Glacial History ................................................................... 3 -

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Manitoba 1870 T 1970 I

El:H E Q1UiBURN ~ MANITOBA 1870 T 1970 I Oakburn Centennial Committee Oakburn, Manitoba Litho by D. W. Friesen & SoilS Ltd., AltOM, Monitobo, Conodo mJ OAKBURN HISTORY BOOK COMMITTEE Sitting left to right are: Ann Bucklaschuk, Peter Majko, Nell J. Hl"ytsak, Ann Prosyk, Annette Majko, Olga Yal"ish. CENTENNIAL COMMITTEE Executive - President - Mike Michalyshyn Vice President - Mike Borodie Secretary-Treasurer -- Stephen Waytowich Planning Committee - Julian Lucyshen Peter Matiation Lena Nychek Program Committee - Nell J. Hrytsak Anne Prosyk Alex Matiowski Mary Borodie Jean Matiation Tony Slon Olga Yarish Alex Prosyk III Foreword The principle objective of this book is to inspire in the hearts of the future generations an understanding that the development and progress of a country is dependent upon its human resources. It is the quality of the people and their aspirations and resourcefulness which determines whether a nation will grow to become strong and unified. The 19th and 20th centuries saw a great flood of people pour into Canada from the continent of Europe. Many of these early immigrants came to this land in search of religious and political freedom which they were being denied in their homeland. Adverse economic conditions forced others to seek a new life in a strange land, and there were the romantics who came to Canada in search of new adventures, fell in love with the land and stayed. All of these people brought with them to this new land not only their families and a few worldly possessions, but also their hopes, ideals, and ways of life. Out of the wilderness they helped to carve a unique nation with a character of its very own called Canada. -

Community MUNICIPALITY ABIGAIL MUNICIPALITY of BOISSEVAIN

Community MUNICIPALITY ABIGAIL MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ADELPHA MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON AGHAMING INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS AGNEW RM OF PIPESTONE AIKENS LAKE INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS AKUDLIK TOWN OF CHURCHILL ALBERT RM OF ALEXANDER ALBERT BEACH RM OF VICTORIA BEACH ALCESTER MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ALCOCK RM OF REYNOLDS ALEXANDER RM OF WHITEHEAD ALFRETTA HAMIOTA MUNICIPALITY ALGAR RM OF SIFTON ALLANLEA MUNICIPALITY OF GLENELLA-LANSDOWNE ALLEGRA RM OF LAC DU BONNET ALLOWAY RIVERDALE MUNICIPALITY ALMASIPPI RM OF DUFFERIN ALPHA RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE ALPINE MUNICIPALITY OF SWAN VALLEY WEST ALTAMONT MUNICIPALITY OF LORNE ALTBERGTHAL MUNICIPALITY OF RHINELAND AMANDA RM OF ALEXANDER AMARANTH RM OF ALONSA AMBER RM OF MINTO-ODANAH AMBROISE SETTLEMENT RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE AMERY Not within a MUNICIPALITY ANAMA BAY INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ANEDA RM OF LAC DU BONNET ANGUSVILLE RM OF RIDING MOUNTAIN WEST ANOLA RM OF SPRINGFIELD APISKO LAKE INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ARBAKKA RM OF STUARTBURN ARBOR ISLAND MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ARDEN MUNICIPALITY OF GLENELLA-LANSDOWNE ARGEVILLE RM OF COLDWELL ARGUE MUNICIPALITY OF GRASSLAND ARGYLE RM OF ROCKWOOD ARIZONA MUNICIPALITY OF NORTH NORFOLK ARMSTRONG SIDING MUNICIPALITY OF WESTLAKE-GLADSTONE ARNAUD MUNICIPALITY OF EMERSON-FRANKLIN ARNES RM OF GIMLI Community MUNICIPALITY ARNOT INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ARONA RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE ARROW RIVER PRAIRIE VIEW MUNICIPALITY ASESSIPPI RM OF RIDING MOUNTAIN WEST ASHBURY RM OF WHITEHEAD -

Public Accounts of the Province of Manitoba for the Year Ended 31St March, 1960

0 1620 0749 0426 i , ■ _ ' * PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF THE PROVINCE OF MANITOBA FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31st MARCH, 1960 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA for the Province of Manitoba, 1960 EG GOV DOC leferenc? CAE MA F P71- 1960 ken from ta¬ bard Ex LIBRIS UNiyERSITATIS albertensis PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF THE PROVINCE OF MANITOBA FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31st MARCH, 1960 Printed by R. S. Evans, Queen’s Printer for the Province of Manitoba, 1960 WINNIPEG Un BRARY • a rta To the Honourable Errick F. Willis, Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Manitoba. May It Please Your Honour: The undersigned has the honour to present the Public Accounts of the Province of Manitoba for the year ended 3 1st March, 1960. DUFF ROBLIN, Acting Provincial Treasurer. Office of the Provincial Treasurer. 8th December, 1960. I E | a V ' m The Honourable Dufferin Roblin, Acting Provincial Treasurer of Manitoba. Sir: I have the honour to submit herewith the Public Accounts of the Province of Manitoba for the year ended 31st March, 1960. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, GEO. D. ILIFFE, F.C.A., Comptroller-General Winnipeg, Manitoba, 8th December, 1960. Public Accounts 1959-1960 7 GOVERNMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF MANITOBA ORDER OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS Page Main Statements: Balance Sheet as at 31st March, 1960 . 10 Schedules to Balance Sheet as at 31st March, 1960 . 12 Statement of Revenue and Expenditure for the fiscal year ended 3'lst March, 1960 . 26 Statement of Special Warrants issued during the fiscal year ended 31st March, 1960 . 30 Comparative Statement of Revenue, 1952-4960 . -

Public Accounts of the Province of Manitoba

HIL-GOV L14EF33 R.4 2 6 1986/87 v. 2 accounts 1986-87 UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSW CK LIBRARIES 3 9950 0 27 0924 3 volume 2 — supplementary information Manitoba Finance for the year ended March 31,1987 public accounts 1986-87 volume 2 — supplementary information Manitoba Finance for the year ended March 31,1987 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS 1986-87 GOVERNMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF MANITOBA TABLE OF CONTENTS Salaries and Wages Paid to Employees, for the fiscal year ended March 31,1987. 9 Cash Payments to Corporations, Firms, Individuals, Other Governments and Government Agencies for the fiscal year ended March 31,1987 . 85 Detailed Statement of Cash Payments from Departmental Appropriations for the fiscal year ended March 31st, 1987 . 160 INTRODUCTION TO THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF MANITOBA The Public Accounts of the Province of Manitoba are prepared by statutory requirement, in accordance with the Financial Administration Act, which is Chapter F55 of the Continuing Consolidation of the Statutes of Manitoba. The Public Accounts for the fiscal year ended March 31,1987 consist of two volumes: Volume 1 contains the summary financial statements of the Province and corresponding schedules of supporting information. Volume 2 is a supplementary volume which contains further details of the expenditures by standard expenditure object codes. It also provides details of the salaries and wages paid to employees as well as payments to corporations, firms, individuals, other Governments and Government Agencies. CONTENTS OF VOLUME 1 — FINANCIAL STATEMENTS The contents of this volume are described in the preface to volume 1. CONTENTS OF VOLUME 2 — SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION a) Salaries and Wages in Excess of $25,000 (i) This statement lists employees who received salaries or wages in excess of $25,000 during the fiscal year. -

Assiniboine-Birdtail IWMP

Assiniboine-Birdtail Integrated Watershed Management Plan 2 Assiniboine - Birdtail Integrated Watershed Management Plan A Word from the PMT Chairman Greetings, As the chair of the Assiniboine-Birdtail Watershed Project Management Team, I am pleased to present the first Integrated Watershed Management Plan. It is my hope that this first step may be the beginning of a more thoughtful approach to land use planning. Decisions will address not only the desire to maximize economic profitability, but also the long-term needs and hopes of the broadest segment of this region’s inhabitants, bird, fish and animal as well as human. In this time of climate uncertainty, I am confident that decision makers moving forward will use lessons learned from the past, along with information in the IWMP to guide their decisions, resulting in perpetually sustainable economic activities, and high standards of health and quality of life. My sincere thanks to all who contributed time and knowledge to this project, which would not have come to be without them. Geordie Daneliuk Chair, Assiniboine-Birdtail Project Management Team Honourable Christine Melnick Minister of Water Stewardship Assiniboine - Birdtail 3 Integrated Watershed Management Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 Watershed Goals & Objectives 11 Implementation Plan 22 Integrated Watershed Management Plan Summary 28 Evaluation and Reporting 28 Appendix A: Watershed Planning Advisory Team - Invite List 30 Appendix B: Summary of Public Input 32 Glossary 38 4 Assiniboine - Birdtail Integrated Watershed Management Plan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Assiniboine‐Birdtail Watershed Planning Authority would like to gratefully acknowledge and thank the Lake of the Prairies & Upper Assiniboine River Conservation Districts, the watershed planning advisory team members, member municipalities, and all watershed residents and stakeholders for their support, input and participation in developing the Assiniboine‐Birdtail Watershed Management Plan. -

Rha Planning Districts 2020

Falloon Nabel Haider Head Commonwealth Lake Goose Lake Nueltin Lake Lake Lake L Ballantyne Todd Coutts Blevins Lopuck Lake Is Lake L Putahow Savage Strachan Lake Lake Hutton L Lake Veal Lake Lake Bulloch Tice Lake Gronbeck Thuytowayasay Lake Round L Lake Lake Nahili John Sand Osborn L Inverarity Lake McEwen COLVIN LAKE Colvin NUELTIN LAKE L Bangle L Lake Koona Lake Kitchen CARIBOURIVER Lake Lake Lake Vinsky Gillander Gagnon Jonasson Ewing L L Kasmere Lake Drake Guick Ashey Lake Lake PROVINCIAL PARK Sucker Sandy L Lake Nejanilini Lake Lake L Shannon PARKRESERVE Corbett Lake HUDSON Turner Secter Croll Lake Lake Lake L PROVINCIAL PARK Butterworth Lemmerick Creba Lake Lake Lake L Long Tatowaycho Little Lake L Duck Jethe MacMillian Booth Bambridge Grevstad Lake Lake L Hubbart Point L Lake Lake Baird Gross Lake Hillhouse DuckLake Post Caribou Snyder Lake L Lake Lake L Alyward L Sandhill Ibbott Choquette Lake Ferris Lake Lake Palulak Lake FortHall Topp Maughan Barr Lake L L L Mistahi Atemkameskak Lake L Brownstone Oolduywas OuelletLake L Munroe Sothe Sothe Van Der Vennet Lake L L Doig Lake L Quasso L Blackfish Colbeck Lake Macleod Warner L Lake Lake Lake Lake Cangield Thuykay L Naelin L Endert Minuhik Adair Point of the Woods Whitmore Greening Lake Lake Lake Law Lake Tessassage L Duffin Hoguycho Spruce L Lake Lake Copeland Lake Lake Weepaskow Egenolf Lake Lakes L Birch Numaykos Meades Knife Blenkhorn Kerek Canoe Howard L Apeecheekamow L Lake Lake Delta Chatwin Lake Lake North River Mcgill Lake Daggitt Lake Quaye Misty Lake Lake Dunlop Ireland -

Settlement Services for New Immigrants in Manitoba As of October 31, 2013

Settlement Services for New Immigrants in Manitoba As of October 31, 2013 Centralized Services in Winnipeg Manitoba Start • Centralized intake service for new immigrants in Winnipeg 271 Portage Avenue, Wpg. R3B 2A8 It is the first stop after newcomers arrive to MB, and the starting Intake: 204-944-8833 Fax 204-944-8787 point for receiving info and referrals to employment and settlement Email: [email protected] services Web: www.manitobastart.com • Employment Services – Offers employment preparation Contact Jonathan Bauer – Outreach Coordinator workshops; one-on-one career coaching; and a job matching unit ENTRY Program • Clients must first go to Manitoba START to get a referral to the 400 - 259 Portage Avenue. Wpg. R3B 2A9 ENTRY Program Phone : 204-944-0133 Fax: 204-944-8062 • Orientation and language for newcomers Email: [email protected] • Newcomers learn about employment services, getting settled in Web: www.entryprogram.ca Winnipeg, health services and the law Contact: Grace Eidse, Executive Director • Regular program is 4 weeks, but they also offer a 1 week express for those proficient in English • Classes offered mornings, afternoons and evenings Winnipeg English Language Assessment & • Clients must first go to Manitoba START to get a referral to Referral Centre (WELARC) WELARC # 400 - 275 Portage Avenue R3B 2B3 • English language assessments for adults before they can take Phone: 204-943-5387 Fax: 204-943-9614 English language classes or training programs Email : [email protected] • Referrals to settlement services or -

The Russell BANNERANNER

Tuesday, April 22nd, 2014 The Russell BANNERANNER Volume No. 117, Issue No. 16 PM40007652 $1.25 Taxes included ~ Serving Russell & Area ~ Cheryl Melnyk brought in some freshly sheared wool. Jeff Kostiuk had some hemp Jewel Mazur and her new buddy Herb the ‘people’ sheep Isobel Wendell brought in her honey hives The Enviroscape.... What an adventure it was By Terrie Welwood And of course, there must be a tractor..... There was flax and even a It was all part of the Amaz- The Amazing Agriculture Current information about and Simple Machines. banker or two. There was a ing Ag Adventure. Adventure is a cooperative agriculture to the students in Students move through 16 - man explaining about some- And what a great day of ad- effort of Ag in the Class- our school system.” 18 interactive stations cover- thing called hemp, a lady ex- venture and learning it was. room, Manitoba Agriculture The Amazing Agriculture ing a variety of agriculture plaining watersheds and how Last week grades 4 and 5 (MAFRI) and a number of ag Adventure is a hands-on, in- topics. they affect our lives and an- students from around the area based businesses. teractive event geared to the This program costs $3.00 other lady who makes honey - Roblin, Rossburn, Beniota, Ag in the Classroom is a Grades 4 and 5 Science cur- per student. even brought her hives along Grandview, Miniota, Bin- non profit organization aimed riculums. Various activities While it’s been running in to show! scarth and Inglis joined their at connecting students to agri- are centered around Habitats Winnipeg and Brandon for And of course, there was a Major Pratt counterparts in culture. -

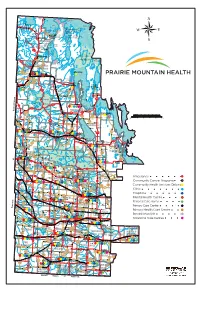

PMH Regional Map

Little Haider Goose Lake Putahow Nueltin Head River Ballantyne L Falloon Egg Lopuck Lake Commonwealth L Partridge Lake Todd Lake Nabel Is Lake Lake Strachan Putahow Blevins Coutts Veal L Lake Lake Lake Tice Lake Savage Lake Hutton Lake Lake Lake Dickins R Nahili Bulloch COLVIN LAKE Colvin L John Lake R Lake Koona Osborn Round Gronbeck Thuytowayasay NUELTIN LAKE L Jonasson Gillander Lake Bangle Inverarity Sand L Lake L Kasmere Lake Lake Lake Lake PROVINCIAL PARK McEwen Sucker Drake Ewing Kitchen CARIBOU RIVER Lake Sandy L Guick Ashey Lake Kirk L Lake L Lake Shannon Lake Gagnon Vinsky Secter L Hanna L River Turner Corbett Lake Nejanilini Lake Butterworth Lake Lemmerick Creba Lake Croll PARK RESERVE Ck Lake Lake PROVINCIAL PARK L Lake Kasmere Lake Falls Tatowaycho R Creek L Grevstad Thlewiaza Caribou HUDSON Bartko MacMillian Lake Hillhouse Booth Little Long Snyder L Lake Bambridge Lake Lake Duck Jethe Lake Lake L Baird Lake L Ibbott Alyward Lake Duck Lake Post River Lake Choquette L Caribou Gross Hubbart Point Lake Sandhill Wolverine Lake L Fort Hall Lake Topp L Maughan Clarke River Ouellet Lake L L Ferris Atemkameskak Big Van Der Vennet Mistahi Lake Palulak L L Brownstone Barr Quasso L L Colbeck Doig Munroe Oolduywas Lake Lake Lake L Blackfish Lake Lake Lake Spruce Lake Sothe Sothe Macleod L Endert Cangield L Whitmore Minuhik R Law Lake L Lake Cochrane R Lake Lake Warner Lake Adair Naelin Thuykay Tessassage Greening L Lake L Lake Weepaskow North Lake Duffin Egenolf Lake Hoguycho Numaykos L Copeland Spruce Point of the Woods Lake L River