A Meta-Analysis of Feuerstein's Instrumental Enrichment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xxi 84 2014 E D I Ç Ã O 8 4 4 8 O Ã Ç I D ANO XXI - E ANO XXI - Julho 2014 - Nº84

ANO edição julho xXI 84 2014 ANO XXI ANO ANO XXI - Julho 2014 - nº84 - e d i ç ã o 8 4 julho 2014 julho CAPA Imagem estilizada do quadro ANO edição julho xXI 84 2014 “A Sinagoga”, óleo sobre tela, Marc Chagall, 1917 TESTE-CAPA84c(provaprelo).indd 1 26-Jun-14 7:15:33 AM Carta ao leitor Tishá b´Av, o nono dia do mês hebraico de Menachem finanças, medicina também estão fora de proporção com Av, é o dia mais triste do calendário judaico – a data em seu pequeno número. Têm feito uma luta maravilhosa no que foram destruídos ambos os Templos de Jerusalém. mundo, em todas as épocas; e o têm feito com as mãos Desde a queda do Segundo Templo, vários eventos atadas nas costas (...)”. trágicos – tanto para o Povo Judeu como para o restante da humanidade – ocorreram nessa data. As palavras de Mark Twain reverberaram ao longo dos séculos. O que ele escreveu a respeito do Povo Judeu O nono dia de Av e as Três Semanas de Luto que o vale especialmente para a geração que sobreviveu ao precedem são dias de autorreflexão, em que devemos fazer Holocausto, reconstituiu um Estado Judeu na Terra de um exame de consciência, tanto individual como coletivo. Israel e fez com que o judaísmo voltasse a florescer. Contudo, o judaísmo não vê com bons olhos a tristeza. “Somos a geração de Jó e de Jerusalém”, escreveu Elie Diz um ensinamento judaico que tudo que ocorre na vida Wiesel. De fato, a geração do Holocausto sofreu mais é para o bem e que devemos nos esforçar para enxergar a do que qualquer outra. -

Concentrated Reinforcement Lessons (Corel) Madeleine J

Concentrated Reinforcement Lessons (CoReL) Madeleine J. Long The American Association for the Advancement of Science CoReL was created by Reuven Feuerstein to prepare under-schooled Ethiopian immigrant students for successful integration into Israeli mainstream classrooms. Feuerstein is a leading cognitive psychologist, apprentice of Karl Jaspers, Carl Jung, Andrey Rey and Jean Piaget, and supporter of Lev Vygotsky’s work. He based CoReL on the tradition of socio-psychological theory and research on the differential effects of culture and cultural deprivation (devaluation of a minority culture) on the development of children’s learning abilities and cognitive functions. The concept for CoReL was developed within the context of two decades of experiences with under-schooled immigrant children from North Africa and the former Soviet Union. The Israeli experience made obvious an interesting—and hopeful—juxtaposition of factors. On the one hand, it was clear that without special attention and preparation these groups would perform poorly on language and academic skills tests. On the other hand, the same groups would often show unexpected strength in specific tests of cognitive abilities, and would almost always show normal learning propensities. CoReL was created in Israel to provide the conditions for a rapid integration of culturally- different immigrant students from Ethiopia into the regular educational system. CoReL was expected to make it possible for culturally different students, who are often unable to reveal their true learning potential in standard psycho-educational assessments, to demonstrate their abilities, and thus avoid being misjudged and tracked into inappropriate educational environments. CoReL operated through a process of: o Identifying the learning abilities of the new immigrant children and building an intervention system for their successful transition into the mainstream. -

There Is No Point of No Return

ב“ה An inspiring story for your Shabbos table ערב יום כפור, ט‘ תשרי, תשע״ח HERE’S Erev Yom Kippur, September 29, 2017 my STORY THERE IS NO POINT Generously OF NO RETURN sponsored by the PROFESSOR REUVEN FEUERSTEIN help them change because they are human beings who have a divine spirit in them.” At the time I advanced this theory — that human beings are modifiable, that they are not necessarily limited by their genetics — it was considered heresy. People simply did not believe that the brain could change, although now it is an accepted fact that there is no part of the body as flexible and changeable as the brain. The Rebbe knew about my work and totally supported it. He frequently sent children to me – some with developmental problems, some with Down syndrome, and some who were epileptic. Wherever I went, people were coming up to me, saying, “The Rebbe wants you to see our child.” As well, I received letters from the Rebbe about particular children whom he wanted me to see. Each time he sent me a referral it was accompanied by his blessing, “Zayt matzliach — May you be successful.” With that blessing, I got a feeling of empowerment — that, no matter how very difficult the case, I could help this s a psychologist working in Israel during the 1940s, particular child. I saw that he believed that even people I worked with Holocaust survivors, many of them with genetic disorders could be turned into functioning children, who were absolutely traumatized. For individuals who could be brought close to Judaism, who A could study Torah. -

El Desarrollo Del Potencial De Aprendizaje Entrevista a Reuven Feuerstein

Para citar este artículo, le recomendamos el siguiente formato: Noguez, S. (2002). El desarrollo potencial de aprendizaje. Entrevista a Reuven Feuerstein. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 4 (2). Consultado el día de mes de año en: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol4no2/contenido-noguez.html Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa Vol. 4, No. 2, 2002 El desarrollo del potencial de aprendizaje Entrevista a Reuven Feuerstein The Development of the Potential of Learning An Interview with Reuven Feuerstein Sergio Noguez Casados [email protected] Dirección de Formación Valoral Universidad Iberoamericana, Santa Fe Edificio J, Tercer piso Prolongación Paseo de la Reforma 880 Lomas de Santa Fe, 01210 México, D. F., México Resumen A través de las respuestas que el Dr. Reuven Feuerstein nos ofrece en esta entrevista, podemos tener una primera aproximación al trabajo que él ha venido realizando desde hace más de 40 años. Su línea de trabajo se inscribe en la psicología cognitiva estructural con un interesante apoyo en nuevos usos de herramientas típicas de la psicometría, aunque, con énfasis en el desarrollo de habilidades del pensamiento, y no en medir o señalar coeficientes de inteligencia. El Dr. Feuerstein nos brinda un balance actual de sus campos de trabajo más importantes, los cuales tienen aplicación en diferentes ámbitos de la educación, desde preescolar hasta entrenamiento de pilotos de alta tecnología. Noguez Casados: El desarrollo del potencial de... Palabras clave: Modificabilidad cognitiva, operaciones mentales, funciones cognitivas deficientes, mediación del aprendizaje, mapa cognitivo, aprendizaje mediado. Abstract Dr Reuven Feurstein’s answers to this interview provide a first approximation to the work he has been doing for the last 40 years. -

Answers of Feuerstein

Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa Vol. 4, No. 2, 2002 The Development of the Potential of Learning An Interview with Reuven Feuerstein Sergio Noguez Casados [email protected] Dirección de Formación Valoral Universidad Iberoamericana, Santa Fe Edificio J, Tercer piso Prolongación Paseo de la Reforma 880 Lomas de Santa Fe, 01210 México, D. F., México Abstract Dr Reuven Feurstein’s answers to this interview provide a first approximation to the work he has been doing for the last 40 years. It belongs to the area of structural cognitive psychology, with an interesting new use of the typical tools of psychometry focused on the development of thinking skills, not on IQ testing. Dr. Feuerstein offers a current balance of the most important fields he has been working on, which can be applied to different educational settings, from preschool to the training of High-Tech pilots. Key words: Cognitive modifiability, mental operations, deficient cognitive functions, mediated learning, cognitive map. Reuven Feuerstein was born in 1921 in Botosan, Romania, one of nine children in the family of a scholar in Jewish Studies. He immigrated to Israel in 1944. He is married to Berta Guggenheim Feuerstein and has four children. He and his family currently reside in Jerusalem, Israel. Feuerstein attended Teachers College in Bucharest (1940-41) and Onesco College in Bucharest (1942-44) but had to save his life by fleeing before obtaining a degree in psychology,. From 1944-45 he attended the Teacher Training Seminary in Jerusalem. He resumed Noguez Casados: The development of the potential… his education in 1949 in Switzerland where he attended lectures given by Carl Jaspers, Carl Jung, and L. -

Cover Story - the Transformer

6/29/2010 Cover Story - The Transformer Reuven Feuerstein is the quintessential believer in the power of the human spirit. Just ask 16-year-old Alex, the English boy who had half his brain surgically removed and who experts said would, at best, attain the mental level of an idiot. Alex Oliver is not Jewish, but for the past year he has lived in Jerusalem, at Professor Feuerstein's Center for Learning Potential, where his progress has defied his dismal diagnosis by the British medical community. Alex was born with a disorder of the blood vessels in his brain, leading to epileptic seizures. From infancy to age seven, Alex's fits were kept in check by daily doses of powerful drugs, yet he hadn't learned to speak. One day his brother accidentally took Alex's medication and lost the ability to talk. Alex's brother didn't say a word for five days, behaving much like a severely mentally handicapped child. At that point, Alex's mother, Helena, realized how Alex's medication had handicapped him, and understood that if she ever wanted him to have a shot at a normal life, he had to get off the medication. Undaunted by pessimistic medical predictions, Mrs. Oliver collected a team of neurologists and a neurosurgeon to remove the damaged left half of Alex's brain; they hoped this would enable the right brain to begin functioning properly. The operation was a surgical success; when the drugs were halted, Alex even began to speak. But after years in a special school, Alex was still unable to read, write or do arithmetic. -

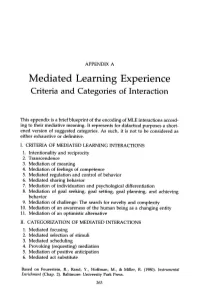

Mediated Learning Experience Criteria and Categories of Interaction

APPENDIX A Mediated Learning Experience Criteria and Categories of Interaction This appendix is a brief blueprint of the encoding of MLE interactions accord ing to their mediative meaning. It represents for didactical purposes a short ened version of suggested categories. As such, it is not to be considered as either exhaustive or definitive. I. CRITERIA OF MEDIATED LEARNING INTERACTIONS 1. Intentionality and reciprocity 2. Transcendence 3. Mediation of meaning 4. Mediation of feelings of competence 5. Mediated regulation and control of behavior 6. Mediated sharing behavior 7. Mediation of individuation and psychological differentiation 8. Mediation of goal seeking, goal setting, goal planning, and achieving behavior 9. Mediation of challenge: The search for novelty and complexity 10. Mediation of an awareness of the human being as a changing entity 11. Mediation of an optimistic alternative II. CATEGORIZATION OF MEDIATED INTERACTIONS 1. Mediated focusing 2. Mediated selection of stimuli 3. Mediated scheduling 4. Provoking (requesting) mediation 5. Mediation of positive anticipation 6. Mediated act substitute Based on Feuerstein, R., Rand, Y., Hoffman, M., & Miller, R. (1980). Instrumental Enrichment (Chap. 2). Baltimore: University Park Press. 263 264 APPENDIX A 7. Mediated imitation 8. Mediated repetition 9. Mediated reinforcement and reward 10. Mediated verbal stimulation 11. Mediated inhibition and control 12. Mediated provision of stimuli 13. Mediated recall short-term 14. Mediated recall long-term 15. Mediated transmission of past 16. Mediated representation of future 17. Mediated identification and description-verbal 18. Mediated identification and description-nonverbal 19. Positive verbal response to mediation 20. Positive nonverbal response to mediation 21. Mediated assuming responsibility 22. -

Answers of Feuerstein

Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa Vol. 4, No. 2, 2002 El desarrollo del potencial de aprendizaje Entrevista a Reuven Feuerstein The Development of the Potential of Learning An Interview with Reuven Feuerstein Sergio Noguez Casados [email protected] Dirección de Formación Valoral Universidad Iberoamericana, Santa Fe Edificio J, Tercer piso Prolongación Paseo de la Reforma 880 Lomas de Santa Fe, 01210 México, D. F., México Resumen A través de las respuestas que el Dr. Reuven Feuerstein nos ofrece en esta entrevista, podemos tener una primera aproximación al trabajo que él ha venido realizando desde hace más de 40 años. Su línea de trabajo se inscribe en la psicología cognitiva estructural con un interesante apoyo en nuevos usos de herramientas típicas de la psicometría, aunque, con énfasis en el desarrollo de habilidades del pensamiento, y no en medir o señalar coeficientes de inteligencia. El Dr. Feuerstein nos brinda un balance actual de sus campos de trabajo más importantes, los cuales tienen aplicación en diferentes ámbitos de la educación, desde preescolar hasta entrenamiento de pilotos de alta tecnología. Palabras clave: Modificabilidad cognitiva, operaciones mentales, funciones cognitivas deficientes, mediación del aprendizaje, mapa cognitivo, aprendizaje mediado. Abstract Dr Reuven Feurstein’s answers to this interview provide a first approximation to the work he has been doing for the last 40 years. It belongs to the area of structural cognitive psychology, with an interesting new use of the typical tools of psychometry focused on the development of thinking skills, not on IQ testing. Noguez Casados: El desarrollo del potencial de... Dr. Feuerstein offers a current balance of the most important fields he has been working on, which can be applied to different educational settings, from preschool to the training of High-Tech pilots. -

Laudatio by Professor Stefan Szamosközi, Ph.D. Vice-Rector at Universitatea Babe Ş-Bolyai

Laudatio by Professor Stefan Szamosközi, Ph.D. Vice-rector at Universitatea Babe ş-Bolyai Distinguished professor of Bar Bar-Ilan University School of Education (Ramat Gan, Israel), doctor honoris causa of Charles University in Prague, of University of Turin, Italy, and honored member of Universidad Diego Portales, Chile, the Director of the Hadassah-Wizo-Canada Research Institute, in Jerusalem, and the International Center for Learning Potentail, a source of inspiration for thousands of teachers and psychologists, Professor Reuven Feuerstein devoted all his life to the development of the theory and the practice of Cognitive Structural Modifiability. He is teaching children, teachers, parents, trainers, councilors and psychologists that Intelligence is modifiable all along lifespan, and that a good culture of teaching can shape and scaffold understanding, problem solving, concentration, originality and many other highly valued cognitive abilities. Professor Reuven Feuerstein was born in Boto şani (Romania) in 1921, the fifth of nine children. He went to school in the Yeshiva in Kishinev in Bessarabia (now Moldavia). In 1939-1941 he studied in Bucharest (Romania) at the Teachers College of the Jewish community, being appointed co-director, in 1941-44 of the Scoala Mixt ă No. 8, “Ap ărătorii Patriei”, where he continued teaching and caring for children in spite of the dramatic conditions of war and antisemitism. He left the country and arrived in Palestine in 1944. During 1944-45 he studied in the Teacher Training Seminar in Jerusalem, afterwards working as teacher and counselor to children and youth who survived from the concentration camps after the Shoah (1945 – 1948). Professor Feuerstein completed his undergraduate studies in 1950 at the University of Geneva (Switzerland) with Prof.