3 Association Ofsouthern Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Fairchild's Plant Hunting Expeditions in Haiti

Working Papers Series David Fairchild’s plant hunting expeditions in Haiti Javier Francisco‐Ortega Marianne Swan William Cinea Natacha Beaussejour Nancy Korber Janet Mosely Latham Brett Jestrow LACC Working Paper No. 2/2017 Miami, FL Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center Florida International University 2 LACC Working Papers Edited by the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center, School of International and Public Affairs, Florida International University The LACC Working Papers Series disseminates research works in progress by FIU Faculty and by scholars working under LACC sponsored research. It aims to promote the exchange of scientific research conducive to policy‐oriented debate in Latin America and the Caribbean. LACC and/or FIU are not responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this Working Paper. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Center. KIMBERLY GREEN LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN CENTER School of International and Public Affairs • College of Arts and Sciences Modesto A. Maidique Campus, DM 353 • Miami, FL 33199 • Tel: 305‐348‐2894 • Fax: 305‐348‐3593 • [email protected] • http://lacc.fiu.edu Florida International University is an Equal Opportunity/Access Employer and Institution • TDD via FRS 800‐955‐8771 3 David Fairchild’s plant hunting expeditions in Haiti Javier Francisco‐Ortega1,2,*, Marianne Swan2, William Cinea3, Natacha Beaussejour3, Nancy Korber2, Janet Mosely Latham4,2, -

OFFICIAL BULLETIN Penna.' Militia, Delegate to State Constitutional Convention of 76

Ol"l"ICIAL BULLETIN N y k C't N y (35648). Son of Samuel and Aurelia EDWARD DALY WRIGHT, ew or 1 Yd C j- (Wells) Fleming· great-grandson of (Fleming) Wright; grandson of H~nry an • aro t~e f John and 'Mary (Slaymaker) Henr! and ~titia ~~p::k:1onFl:t~~~osgr~!~~:;er:onpr~vate, Lancaster County, Penna. Flemmg, Jr. • great gr f H Sl ker Member Fifth Battalion, Lancaster County, 1t-1ilitia · great'· grandson o enry ayma , . , OFFICIAL BULLETIN Penna.' Militia, Delegate to State Constitutional Convention of 76. ALVIN LESKE WYNNE Philadelphia, Penna. (35464). Son of Samuel ~d Nettle N. ~J--j OF THE Wynne, Jr.; grandso; of Samuel Wynne; great-grandson of_ !~mes ynne; great -gran - son of Jonatluln Wynne, private, Chester County, Penna, Mthtla. y k c· N y (35632) Son of Thomas McKeen and Ida National Society THO:AS BY~UN~~u~=~ gra~~son '~· Wiilia~ and Reb~cca (Goodrich) Baker; great-grandson /YE~-:h e:~d Rachel (Lloyd) Goodrich; great•-grandson of Jol•n !:loyd,. Lieutenant, of the Sons of the American Revolution 0New ~ork Militia and Cont'l Line; greatl..grandson of Miclwel Goodrtch, pnvate, Conn. Militia and Cont'l Troops. R THOMAS RINEK ZULICH, Paterson, N. J. (36015). Son of Henry B. and Emma · (Hesser) Zulicb; grandson of Henry and Margaret (_S_h.oemake~) Hesser; great-grandson of Frederick Hesser. drummer and ~rivate, Penna. Mthtla, pensiOned. President General Orsranized April 30, 1889 WALLACE McCAMANT Incorporated by Northwestern Bank Buildinsr Act of Consrress, June 9, 1906 Portland, Orellon Published at Washinsrton, D. C., in June, October, December, and Marcb. -

When Dr. Fairchild Visited Miss Sessions: San Diego 19191

Front side of Meyer Medal. Courtesy of the San Diego Historical Society. 74 WHEN DR. FAIRCHILD VISITED MISS SESSIONS: SAN DIEGO 19191 ■ By Nancy Carol Carter n 1939, Kate Sessions received the prestigious Frank N. Meyer Medal for distinguished services in plant introduction by the American Genetics Association. IShe joined the ranks of previously recognized male botanists, including Louis Charles Trabut, a French doctor teaching at the University of Algiers; Henry Nicholas Ridley, an Englishman who learned to tap the rubber tree for latex; Palemon Howard Dorsett, who spent the 1920s identifying plants in China and Japan; and wealthy amateur plant explorers Barbour Lathrop and Allison V. Armour. It was thirty years before another woman received the same honor.2 Sessions was nominated for the award by David Fairchild, plant explorer, botanist and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) official. A newly-explored archive of letters, photographs and manuscripts at the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden expands our knowledge of their relationship. Their seventeen-year-long correspon- dence suggests that he was the most enduring and influential of her professional contacts.3 This article reveals both the professional and the personal nature of their relationship, giving us a more nuanced understanding of Kate Sessions herself. By the end of the nineteenth century, botany had moved almost entirely from its Enlightenment origins as a proper and recommended activity for women and children to a professionalized and almost exclusively male pursuit within the science culture. Some exceptional women made a place for themselves in the field at this early date, but had to overcome barriers. -

Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 Toni Carrier University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Carrier, Toni, "Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 by Toni Carrier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Trevor R. Purcell, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Social Capital, Political Economy, Black Seminoles, Illicit Trade, Slaves, Ranchos, Wreckers, Slave Resistance, Free Blacks, Indian Wars, Indian Negroes, Maroons © Copyright 2005, Toni Carrier Dedication To my baby sister Heather, 1987-2001. You were my heart, which now has wings. Acknowledgments I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the many people who mentored, guided, supported and otherwise put up with me throughout the preparation of this manuscript. To Dr. -

Plant Invasions: Policies, Politics, and Practices

Plant Invasions: Policies, Politics, and Practices PLANT INVASIONS: POLICIES, POLITICS, AND PRACTICES Proceedings of the 5th Biennial Weeds Across Borders Conference Edited by Emily Rindos 1– 4 JUNE 2010 NATIONAL CONSERVATION TRAINING CENTER SHEPHERDSTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA, USA Suggested citation: Name of author(s). 2011. Paper title. Page(s) __ in E. Rindos, ed., Plant Invasions: Policies, Politics, and Practices, Proceedings of the 2010 Weeds Across Borders Conference, 1–4 June 2010, National Conservation Training Center, Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University, Center for Invasive Plant Management. Design: Emily Rindos Copyright © 2011 Montana State University, Center for Invasive Plant Management Weeds Across Borders 2010 Coordinating Committee Stephen Darbyshire, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Jenny Ericson, US Fish and Wildlife Service Francisco Espinosa García, UNAM–National University of Mexico Russell Jones, US Environmental Protection Agency Cory Lindgren, Canadian Food Inspection Agency Les Mehrhoff, Invasive Plant Atlas of New England Gina Ramos, US Bureau of Land Management www.weedcenter.org/wab/2010 Produced by: Center for Invasive Plant Management 235 Linfield Hall, PO Box 173120 Montana State University Bozeman, MT 59717-3120 www.weedcenter.org Table of Contents Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................................................vii Weeds Across Borders 2010 Sponsors .....................................................................................................viii -

Monthly Catalogue, United States Public Documents, July 1914

Monthly Catalogue United States Public Documents Nos. 235-246 July, 1914-June, 1915 ISSUED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS WASHINGTON 1914-1915 Monthly Catalogue United States Public Documents No. 235 July, 1914 ISSUED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS WASHINGTON 1914 Abbreviations Appendix......................................................app. Part, parts...............................................pt., pts. Congress............... Cong. Plate, plates..................................................... pl. Department.................................................Dept. Portrait, portraits.......................................... por. Document......................................................doc. Quarto.............................................. 4- Facsimile, facsimiles...................................facsim. Report.............................................................rp. Folio................................................................. f° Saint................................................................St. House.............................................................. H. Section, sections.............................................. seo. House concurrent resolution.....................H. C. R. Senate............................................................... S. House document........................................H. doc. Senate concurrent resolution.................... S. C. R. House executive document...................H. ex. doc. Senate document....................................... S. -

The Viceroyalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of An

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 7-1-2016 The iceV royalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of an Imperial City John K. Babb Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000725 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Latin American History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Babb, John K., "The icV eroyalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of an Imperial City" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2598. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2598 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE VICEROYALTY OF MIAMI: COLONIAL NOSTALGIA AND THE MAKING OF AN IMPERIAL CITY A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by John K. Babb 2016 To: Dean John Stack Green School of International and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by John K. Babb, and entitled The Viceroyalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of an Imperial City, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. ____________________________________ Victor Uribe-Uran ____________________________________ Alex Stepick ____________________________________ April Merleaux ____________________________________ Bianca Premo, Major Professor Date of Defense: July 1, 2016. -

70Years After David Fairchild's Famous Exploration, We Return to the Spice

fa l l 2 0 1 0 70 years after David Fairchild’s famous exploration, we retu n to the Spice Islands published by fairchild tropical botanic garden tropical gourmet foods home décor accessories The Shop eco-friendly and fair trade products gardening supplies unique tropical gifts AT FAIRCHILD books on tropical gardening, cuisine and more Painted Sparrow, $10 Starling Salt and Pepper Shakers, $18 fairchild tropical botanic garden 10901 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL 33156 • 305.667.1651, ext. 3305 • www.fairchildgarden.org • shop online at www.fairchildonline.com Photo by Gaby Orihuela FTBG contents The trip of David Fairchild’s Lifetime: Fairchild’s Work in the Caribbean: Jamaica A Return to the Spice Islands, 32 23 Melissa E. Abdo, Pamela McLaughlin, Keron Campbell, Carl Lewis Brett Jestrow, Eric von Wettberg 5 FROM THE DIRECTOR 8 EVENTS 9 NEWS 11 TROPICAL CUISINE 13 WHAT’S BLOOMING 15 EXPLAINING 17 VIS-A-VIS VOLUNTEERS 20 PLANT SOCIETIES 49 PLANTS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD 51 BUG BEAT 52 GIFTS AND DONORS 53 WISH LIST My Encounter in the Galapagos, 54 VISTAS Georgia Tasker 42 55 WHAT’S IN STORE 56 GARDEN VIEWS 60 FROM THE ARCHIVES 10901 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL 33156 • 305.667.1651, ext. 3305 • www.fairchildgarden.org • shop online at www.fairchildonline.com www.fairchildgarden.org 3 MATCH AND RIDE New Trams for Fairchild The Donald and Terry Blechman Tribute Fund: Match and Ride What do you remember most about your visit to Fairchild? The beauty? The vistas? The palms? Probably all of these. But you’re most likely to remember enjoying a tram tour of Fairchild insightfully narrated by one of our dedicated and knowledgeable volunteers. -

Educational Directory, 1919-20. Part 7

Bulletin, 1919, No. 71.Fart 7. January, 1920. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR. BUREAU OF EDUCATION, WASHINGTON, D. C. EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORY, 1919-20.PART 7: MISCELLANEOUS EDUCATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS:. CONTENTS:. Educational bards and foundationsChurch educational boards ents of Cull and societiesSuperintend- par,cliial sob° )1,Jewish educational organizations Directorsof school. of phil- anthropyInternational associations of educationAmerican pducationalassociations: (1) National and sectt.inal: (2) state: (1) cityLearned and civic organizations--StateFedelations of women's clubsNational Congress of Mothers and Parc:it-TeacherAssociationsEducational periodicals. EDUCATIONAL. BOARDS AND FOUNDATIONS. Name of board. l'resident. Secretary. Meeting. Anna T. Jeanes Founda-James!" Dillard, Box 418, bon. John T. F.mlen, 4th andNewYork,N. Y., Charlottesville, Va. Chestnut Ste., Philadeb Jan. 24, 1920. Baron de Ifirscb Fund phia, l's. E. S. Benjamin, 130 EastMai J. Kohler, 52 WilliamNew York N. Y., third 25 t hSt., New York, St., New York, N. N. Y. N.Y.Y. Sunday in January. Carnegie Corporation of New York. James Bertram, 576 5thNew York, N.Y., Ave.ew YOrk, N. Y. Nov. 20, 1919. Carnegie Foundation forHenry S.Pritchett,5765thClydeFFurst,5765th Ave., the Advamement of Ave., New York, N. Y. New York, N.Y., Teaching. New York, N.Y , . Nov. 19, 191. General EducationWallace B ut t r lc k, 61Abraham F le xner. 61 Board. Broadway, New York, New York, N.Y., N.Y. Broadway, New York, Dee. 4, 1919. John F. Slater Fund.... N.Y. James H. Dillard, Box 418,Miss 0. C. Mann, Box 418,New York, N.Y., Charlottesville, Va. Charlottesville, Va. December, 1919. Kahn Foundation forEdward D. -

The World Was His Garden

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy & Religious Studies 2020 The World Was His Garden Anne-Taylor Cahill Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/philosophy_fac_pubs Part of the Food Studies Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Original Publication Citation Cahill, A.-T. (2020). The world was his garden. Nineteenth Century, 40(1), 46-47. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy & Religious Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Milestones The world was His Garden Anne-Taylor Cahill Very few of us are familiar with the name david Fairchild (1869- one last ploy. Trying to prove he was an American, he showed the 1954), yet every time we go to the grocery store we reap the police an envelope from America with a stamp with the picture of benefits of his life’s work. david Fairchild was a botanist, Ulysses S. Grant on it. “Americano! Americano!” the police adventurer and food explorer. He brought many of the fruits and shouted. They slapped him on the back and let him go with a firm vegetables we eat today to America. He also brought the blossoming cherry trees to washington, d. C. when he was 10 his family moved to Kansas where his father became president of Kansas State Agricultural College. Growing up in an agricultural atmosphere, Fairchild began experimenting with flowering plants, fruits and vegetables. -

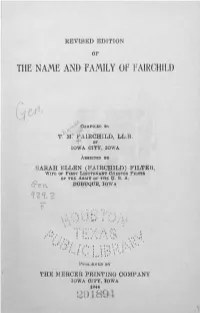

The Name and Family of Fairchild

REVISED EDITION OF THE NAME AND FAMILY OF FAIRCHILD tA «/-- .COMPILED BY TM.'FAIRCHILD, LL.B. OP ' IOWA CITY, IOWA ASSISTED BY SARAH ELLEN (FAIRCHILD) FILTER, WIPE OP FIRST LIEUTENANT CHESTER FILTER OP THE ARMY OP THE U. S. A. DUBUQUE, IOWA mz I * r • • * • • » < • • PUBLISHED BY THE MERCER PRINTING COMPANY IOWA CITY, IOWA 1944 201894 INDEX PART ONE Page Chapter I—The Name of Fairchild Was Derived From the Scotch Name of Fairbairn 5 Chapter II—Miscellaneous Information Regarding Mem bers of the Fairchild Family 10 Chapter III—The Heads of Families in the United States by the Name of Fairchild as Recorded by the First Census of the United States in 1790 50 Chapter IV—'Copy of the Fairchild Manuscript of the Media Research Bureau of Washington .... 54 Chapter V—Copy of the Orcutt Genealogy of the Ameri can Fairchilds for the First Four Generations After the Founding of Stratford and Settlement There in 1639 . 57 Chapter VI—The Second Generation of the American Fairchilds After Founding Stratford, Connecticut . 67 Chapter VII—The Third Generation of the American Fairchilds 71 Chapter VIII—The Fourth Generation of the American Fairchilds • 79 Chapter IX—The Extended Line of Samuel Fairchild, 3rd, and Mary (Curtiss) Fairchild, and the Fairchild Garden in Connecticut 86 Chapter X—The Lines of Descent of David Sturges Fair- child of Clinton, Iowa, and of Eli Wheeler Fairchild of Monticello, New York 95 Chapter XI—The Descendants of Moses Fairchild and Susanna (Bosworth) Fairchild, Early Settlers in the Berkshire Hills in Western Massachusetts, -

BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK the Florida Keys Begin with Soldier Key in the Northern Section of the Park and Continue to the South and West

CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND HISTORY GEOLOGY AND PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK The Florida Keys begin with Soldier Key in the northern section of the Park and continue to the south and west. The upper Florida Keys (from Soldier to Big Pine Key) are the remains of a shallow coral patch reef that thrived one hundred thousand or more years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch. The ocean level subsided during the following glacial period, exposing the coral to die in the air and sunlight. The coral was transformed into a stone often called coral rock, but more correctly termed Key Largo limestone. The other limestones of the Florida peninsula are related to the Key Largo; all are basically soft limestones, but with different bases. The nearby Miami oolitic limestone, for example, was formed by the precipitation of calcium carbonate from seawater into tiny oval particles (oolites),2 while farther north along the Florida east coast the coquina of the Anastasia formation was formed around the shells of Pleistocene sea creatures. When the first aboriginal peoples arrived in South Florida approximately 10,000 years ago, Biscayne Bay was a freshwater marsh or lake that extended from the rocky hills of the present- day keys to the ridge that forms the current Florida coast. The retreat of the glaciers brought about a gradual rise in global sea levels and resulted in the inundation of the basin by seawater some 4,000 years ago. Two thousand years later, the rising waters levelled off, leaving the Florida Keys, mainland, and Biscayne Bay with something similar to their current appearance.3 The keys change.