When Dr. Fairchild Visited Miss Sessions: San Diego 19191

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Fairchild's Plant Hunting Expeditions in Haiti

Working Papers Series David Fairchild’s plant hunting expeditions in Haiti Javier Francisco‐Ortega Marianne Swan William Cinea Natacha Beaussejour Nancy Korber Janet Mosely Latham Brett Jestrow LACC Working Paper No. 2/2017 Miami, FL Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center Florida International University 2 LACC Working Papers Edited by the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center, School of International and Public Affairs, Florida International University The LACC Working Papers Series disseminates research works in progress by FIU Faculty and by scholars working under LACC sponsored research. It aims to promote the exchange of scientific research conducive to policy‐oriented debate in Latin America and the Caribbean. LACC and/or FIU are not responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this Working Paper. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Center. KIMBERLY GREEN LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN CENTER School of International and Public Affairs • College of Arts and Sciences Modesto A. Maidique Campus, DM 353 • Miami, FL 33199 • Tel: 305‐348‐2894 • Fax: 305‐348‐3593 • [email protected] • http://lacc.fiu.edu Florida International University is an Equal Opportunity/Access Employer and Institution • TDD via FRS 800‐955‐8771 3 David Fairchild’s plant hunting expeditions in Haiti Javier Francisco‐Ortega1,2,*, Marianne Swan2, William Cinea3, Natacha Beaussejour3, Nancy Korber2, Janet Mosely Latham4,2, -

Bum the Dog Floral Wagon for the Kid’S Floral Wagon Parade

Kid’s Floral Wagon Parade Saturday, May 9 8:30-10 am: Be a part of history! Children, families and groups are welcome to join the History Center in our Bum the Dog Floral Wagon for the Kid’s Floral Wagon Parade. Help put the finishing touches to our wagon then don some doggie ears, and march alongside the wagon in a parade from Spanish Village to the Plaza de Panama in the Garden Party of the Century Celebration! the D Each individual or group will receive a commemorative “Participation Ribbon” m o and FREE San Diego County Fair tickets! Adult assistance and collaboration in u g the decoration of the wagon is welcome. B BUM THE DOG Family Days at the History Center History Center Kids Club History Center Tuesday, July 28, 11 am: Celebrate the release of Dr. Seuss’ newest book What Pet Should I Get?, with family activities from 11am - 2pm. History for Half Pints First Friday of every month at 10am. Appropriate for ages 3-6. RSVP required: rsvp#sandiegohistory.org b H lu Friday, May 1: May Day, May Poles & Fairies. is to s C Friday, June 5: Farm to Fair! r id y Center K Find Bum Visit the San Diego History Center in Balboa Park Bum the Dog Kid’s Club is for kids ages 5 -11 and find Bum in one of our galleries to win a prize! who love San Diego and want to learn more about the community and city in which they live. With the help of an adult, cut along the dotted line to sandiegohistory.org make your own Bum’s Book Nook bookmark! Bum’s Springtime Adventures Do you know the story of San Diego’s Balboa Park? h Join m t e Do Bu g Bum the Dog Two people, Kate Sessions and Ephraim Morse, worked together to build Balboa Park and make sure it was in good condition for us to enjoy History Center today. -

OFFICIAL BULLETIN Penna.' Militia, Delegate to State Constitutional Convention of 76

Ol"l"ICIAL BULLETIN N y k C't N y (35648). Son of Samuel and Aurelia EDWARD DALY WRIGHT, ew or 1 Yd C j- (Wells) Fleming· great-grandson of (Fleming) Wright; grandson of H~nry an • aro t~e f John and 'Mary (Slaymaker) Henr! and ~titia ~~p::k:1onFl:t~~~osgr~!~~:;er:onpr~vate, Lancaster County, Penna. Flemmg, Jr. • great gr f H Sl ker Member Fifth Battalion, Lancaster County, 1t-1ilitia · great'· grandson o enry ayma , . , OFFICIAL BULLETIN Penna.' Militia, Delegate to State Constitutional Convention of 76. ALVIN LESKE WYNNE Philadelphia, Penna. (35464). Son of Samuel ~d Nettle N. ~J--j OF THE Wynne, Jr.; grandso; of Samuel Wynne; great-grandson of_ !~mes ynne; great -gran - son of Jonatluln Wynne, private, Chester County, Penna, Mthtla. y k c· N y (35632) Son of Thomas McKeen and Ida National Society THO:AS BY~UN~~u~=~ gra~~son '~· Wiilia~ and Reb~cca (Goodrich) Baker; great-grandson /YE~-:h e:~d Rachel (Lloyd) Goodrich; great•-grandson of Jol•n !:loyd,. Lieutenant, of the Sons of the American Revolution 0New ~ork Militia and Cont'l Line; greatl..grandson of Miclwel Goodrtch, pnvate, Conn. Militia and Cont'l Troops. R THOMAS RINEK ZULICH, Paterson, N. J. (36015). Son of Henry B. and Emma · (Hesser) Zulicb; grandson of Henry and Margaret (_S_h.oemake~) Hesser; great-grandson of Frederick Hesser. drummer and ~rivate, Penna. Mthtla, pensiOned. President General Orsranized April 30, 1889 WALLACE McCAMANT Incorporated by Northwestern Bank Buildinsr Act of Consrress, June 9, 1906 Portland, Orellon Published at Washinsrton, D. C., in June, October, December, and Marcb. -

Downtown/Gaslamp District Hillcrest

Rose U.S. Naval Hospital Garden Desert Garden Zoo Entrance Park Blvd. Park Blvd. Footbridge Carousel Reuben H. Fleet Science Center Morton Bay Village Place Natural Fig Lawn History Museum Inspiration Point Spanish Village Miniature Art Center Park Blvd. Railroad Village Place Pepper Grove Casa Del Zoo Entrance History Center Picnic Area Prado and Playground Theater Casa del Veterns Otto Model Railroad Prado Museum Museum & Center Memorial Centro Museum of Center Photographic Arts Cultural de la Raza Botanical Lily Pond Building House of Hospitality Japanese No Through Traffic Timken Friendship Garden The Prado H Museum w Old Globe Way Globe Old y Restaurant 5 /1 World Beat 6 3 Center En Visitor tr Spreckels Police an Plaza de Center ce Organ Horse Stable Museum Panama Pavilion Zoo of Art Mingei Employee Cafe Parking Mingei Museum San Diego Zoo P SDAI an A Sculpture m er ic Garden El Prado an R d Alcazar . E Lady Presidents Way Carolyn’s Garden pub Palm Canyon Old California Tower Globe P a n Pan American Theater A Cannibals m Plaza California Exhibit e Municipal r Plaza ic Gym a n San Diego International Starlight Balboa Park R Cottages d. Bowl Museum of Man Archery Range W St. Francis VIP Chapel E Balboa Park Lot Balboa Park Marie Hitchcock Archery Range Museum Club Office/Gill Puppet Theater Building Automotive Museum Air and Space N S Museum Old Cactus W Garden Cabrillo Bridge Hwy Hwy 163 163 Visitor Information Center Tram Pick-up/Drop-off Map Key Parking Restaurants Nate’s Point Café Dog Park El Prado Restrooms Redwood Circle Lawn Bowling Greens Sefton Playground Plaza Marston Balboa Drive Point Balboa Drive Balboa Drive Founder’s Kate Sessions Plaza Statues Statue Chess Club Sixth Ave Sixth Ave Hillcrest Downtown/Gaslamp District Laurel St. -

George White Marston Document Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8bk1j48 Online items available George White Marston Document Collection Finding aid created by San Diego City Clerk's Archives staff using RecordEXPRESS San Diego City Clerk's Archives 202 C Street San Diego, California 92101 (619) 235-5247 [email protected] http://www.sandiego.gov/city-clerk/inforecords/archive.shtml 2019 George White Marston Document George W. Marston Documents 1 Collection Descriptive Summary Title: George White Marston Document Collection Dates: 1874 to 1950 Collection Number: George W. Marston Documents Creator/Collector: George W. MarstonAnna Lee Gunn MarstonGrant ConardAllen H. WrightA. M. WadstromW. C. CrandallLester T. OlmsteadA. S. HillF. M. LockwoodHarry C. ClarkJ. Edward KeatingPhilip MorseDr. D. GochenauerJohn SmithEd FletcherPatrick MartinMelville KlauberM. L. WardRobert W. FlackA. P. MillsClark M. FooteA. E. HortonA. OverbaughWilliam H. CarlsonH. T. ChristianE. F. RockfellowErnest E. WhiteA. MoranA. F. CrowellH. R. AndrewsGrant ConardGeorge P. MarstonRachel WegeforthW. P. B. PrenticeF. R. BurnhamKate O. SessionsMarstonGunnWardKlauberMartinFletcherSmithGochenauerMorseKeatingClarkLockwoodHillOlmsteadCrandalWadstromFlackMillsKeatingFooteLockwoodWrightChristianCarlsonConardSpaldingScrippsKellyGrantBallouLuceAngierWildeBartholomewSessionsBaconRhodesOlmsteadSerranoClarkHillHallSessionsFerryWardDoyleCity of San DiegoCity Clerk, CIty of San DiegoBoard of Park CommissionersPark DepartmentMarston Campaign CommitteeThe Marston CompanyMarston Co. StoreMarston for MayorPark -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010. -

Plant Invasions: Policies, Politics, and Practices

Plant Invasions: Policies, Politics, and Practices PLANT INVASIONS: POLICIES, POLITICS, AND PRACTICES Proceedings of the 5th Biennial Weeds Across Borders Conference Edited by Emily Rindos 1– 4 JUNE 2010 NATIONAL CONSERVATION TRAINING CENTER SHEPHERDSTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA, USA Suggested citation: Name of author(s). 2011. Paper title. Page(s) __ in E. Rindos, ed., Plant Invasions: Policies, Politics, and Practices, Proceedings of the 2010 Weeds Across Borders Conference, 1–4 June 2010, National Conservation Training Center, Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University, Center for Invasive Plant Management. Design: Emily Rindos Copyright © 2011 Montana State University, Center for Invasive Plant Management Weeds Across Borders 2010 Coordinating Committee Stephen Darbyshire, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Jenny Ericson, US Fish and Wildlife Service Francisco Espinosa García, UNAM–National University of Mexico Russell Jones, US Environmental Protection Agency Cory Lindgren, Canadian Food Inspection Agency Les Mehrhoff, Invasive Plant Atlas of New England Gina Ramos, US Bureau of Land Management www.weedcenter.org/wab/2010 Produced by: Center for Invasive Plant Management 235 Linfield Hall, PO Box 173120 Montana State University Bozeman, MT 59717-3120 www.weedcenter.org Table of Contents Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................................................vii Weeds Across Borders 2010 Sponsors .....................................................................................................viii -

Monthly Catalogue, United States Public Documents, July 1914

Monthly Catalogue United States Public Documents Nos. 235-246 July, 1914-June, 1915 ISSUED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS WASHINGTON 1914-1915 Monthly Catalogue United States Public Documents No. 235 July, 1914 ISSUED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS WASHINGTON 1914 Abbreviations Appendix......................................................app. Part, parts...............................................pt., pts. Congress............... Cong. Plate, plates..................................................... pl. Department.................................................Dept. Portrait, portraits.......................................... por. Document......................................................doc. Quarto.............................................. 4- Facsimile, facsimiles...................................facsim. Report.............................................................rp. Folio................................................................. f° Saint................................................................St. House.............................................................. H. Section, sections.............................................. seo. House concurrent resolution.....................H. C. R. Senate............................................................... S. House document........................................H. doc. Senate concurrent resolution.................... S. C. R. House executive document...................H. ex. doc. Senate document....................................... S. -

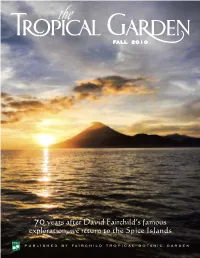

70Years After David Fairchild's Famous Exploration, We Return to the Spice

fa l l 2 0 1 0 70 years after David Fairchild’s famous exploration, we retu n to the Spice Islands published by fairchild tropical botanic garden tropical gourmet foods home décor accessories The Shop eco-friendly and fair trade products gardening supplies unique tropical gifts AT FAIRCHILD books on tropical gardening, cuisine and more Painted Sparrow, $10 Starling Salt and Pepper Shakers, $18 fairchild tropical botanic garden 10901 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL 33156 • 305.667.1651, ext. 3305 • www.fairchildgarden.org • shop online at www.fairchildonline.com Photo by Gaby Orihuela FTBG contents The trip of David Fairchild’s Lifetime: Fairchild’s Work in the Caribbean: Jamaica A Return to the Spice Islands, 32 23 Melissa E. Abdo, Pamela McLaughlin, Keron Campbell, Carl Lewis Brett Jestrow, Eric von Wettberg 5 FROM THE DIRECTOR 8 EVENTS 9 NEWS 11 TROPICAL CUISINE 13 WHAT’S BLOOMING 15 EXPLAINING 17 VIS-A-VIS VOLUNTEERS 20 PLANT SOCIETIES 49 PLANTS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD 51 BUG BEAT 52 GIFTS AND DONORS 53 WISH LIST My Encounter in the Galapagos, 54 VISTAS Georgia Tasker 42 55 WHAT’S IN STORE 56 GARDEN VIEWS 60 FROM THE ARCHIVES 10901 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL 33156 • 305.667.1651, ext. 3305 • www.fairchildgarden.org • shop online at www.fairchildonline.com www.fairchildgarden.org 3 MATCH AND RIDE New Trams for Fairchild The Donald and Terry Blechman Tribute Fund: Match and Ride What do you remember most about your visit to Fairchild? The beauty? The vistas? The palms? Probably all of these. But you’re most likely to remember enjoying a tram tour of Fairchild insightfully narrated by one of our dedicated and knowledgeable volunteers. -

Written Historical and Descriptive Data Hals Ca-131

THE GEORGE WHITE AND ANNA GUNN MARSTON HOUSE, HALS CA-131 GARDENS HALS CA-131 3525 Seventh Avenue San Diego San Diego County California WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY THE GEORGE WHITE AND ANNA GUNN MARSTON HOUSE, GARDENS (The Marston Garden) HALS NO. CA-131 Location: 3525 Seventh Avenue, San Diego, San Diego County, California Bounded by Seventh Avenue and Upas Street, adjoining the northwest boundary of Balboa Park in the City of San Diego, California 32.741689, -117.157756 (Center of main house, Google Earth, WGS84) Significance: The George Marston Gardens represent the lasting legacy of one of San Diego’s most important civic patrons, George Marston. The intact home and grounds reflect the genteel taste of the Marston Family as a whole who in the early 20th century elevated landscape settings, by example, toward city beautification in the dusty, semi-arid, coastal desert of San Diego. The Period of Significance encompasses the full occupancy of the Marston Family from 1905-1987, which reflects the completion of the house construction in 1905 to the death of daughter Mary Marston in 1987. George White Marston (1850-1946) and daughter Mary Marston (1879-1987) are the two notable family members most associated with the design and implementation of the Marston House Gardens, et al. The George W. Marston House (George White and Anna Gunn Marston House) was historically designated by the City of San Diego on 4 December 1970, Historic Site #40. -

The Trees of Balboa Park by Nancy Carol Carter

The Trees of Balboa Park By Nancy Carol Carter Landscape architect Samuel H. Parsons, Jr. noted with enthusiasm the growth of trees and shrubs in City Park when he returned to San Diego in 1910. Five years had elapsed since his New York firm had submitted a comprehensive master plan for the layout of the 1,400 acres set aside as a park in 1868, but mostly left in a natural state for the next few decades. Parsons had returned to San Diego because the city had decided to host an international exposition in 1915. He was hired this time to assess progress on City Park’s master plan and to suggest improvements in all of San Diego’s parks. He thought San Diego had made good progress in engi- neering roads and otherwise fulfilling the landscape plan of City Park.1 His formal report to the park commissioners, submitted June 28, 1910, includes a description of trees and other plantings in the park. By the time Parsons wrote this report, City Park had been in existence for forty-two years and was estimated to contain about 20,000 healthy trees and shrubs. The park commission kept careful records of 2,357 shrubs and vines planted in 1909, but earlier landscape records are sketchy.2 In 1902, Parsons had suggested that the mesas be left open to preserve the stunning views stretching from the mountains to the ocean. “Overplanting is a common mistake everywhere,” he said, “A park is too often perverted to a sort of botanical garden, where a heterogeneous lot of plants are gathered together and massed in a haphazard fashion.”3 He was trying to help San Diegans understand the difference between a park and botanical garden and perhaps obliquely com- menting on the hodgepodge of homegrown efforts to develop the park before 1910.