Separation of Maine from Massachusetts Albert Ames Whitmore University of Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Maine Roads 1600-1970 Maine Department of Transportation

Maine State Library Digital Maine Transportation Documents Transportation 1970 A History of Maine Roads 1600-1970 Maine Department of Transportation State Highway Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs Recommended Citation Maine Department of Transportation and State Highway Commission, "A History of Maine Roads 1600-1970" (1970). Transportation Documents. 7. https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs/7 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Transportation at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transportation Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·-- 7/ I ' .. ·; ""' ~ 0. scanned January 2014 for MA bNE STATE LIBRARY ! H; t. 7-z/9 ?o Si~i{;"b ocs !:ff rifr~ij~fi il i l llll l l l~ ~ l ll l ll l l~ll l · Digital Archive ' :'.::'.Q.1 00088955 9 A Hist or r ...______... .. ~" · "<, ol Maine Roads 1600-1910/ . ~tote Highway Commission / Augusta , Maine A H I S T 0 R Y 0 F M A I N E R 0 A D S State Highway Commim;;ion Augusta, Maine 1970 History of Maine Roads 1600-1970 Glance at a modern map of Maine and you can easily trace the first transportation system in this northeastern corner of the nation, It is still there and in good repair, although less and less used for serious transportation purposes since the automobile rolled into the state in a cloud of dust and excitement at the turn of the century. This first transportation network in the territory that became the State of Maine was composed of waterways - streams, rivers, ponds, lakes and the long tidal estuaries and bays along the deeply indented coast. -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

Land, Timber, and Recreation in Maine's Northwoods: Essays by Lloyd C

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Miscellaneous Publications Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station 3-1996 MP730: Land, Timber, and Recreation in Maine's Northwoods: Essays by Lloyd C. Irland Lloyd C. Irland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/aes_miscpubs Recommended Citation Irland, L.C. 1996. Land, Timber, and Recreation in Maine's Northwoods: Essays by Lloyd C. Irland. Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station Miscellaneous Publication 730. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Miscellaneous Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Land, Timber, and Recreation in Maines Northwoods: Essays by Lloyd C. Irland Lloyd C. Irland Faculty Associate College of Natural Resources, Forestry and Agriculture The Irland Group RR 2, Box 9200 Winthrop, ME 04364 Phone: (207)395-2185 Fax: (207)395-2188 FOREWORD Human experience tends to be perceived as taking place in phases. Shakespeare talked of seven ages of man. More recently Erik Erikson has thought of five separate stages in human life. All of these begin to break down, however, when we think of the end of eras. Partially because of the chronological pressure, such times come at the end of centuries. When one adds to the end of a century the concept of an end of a millennium, the sense of change, of difference, of end time can be very powerful, if not overwhelming. The termination of the nineteenth and the eighteenth centuries were much discussed as to the future. -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

Maine ENERGY SECTOR RISK PROFILE

State of Maine ENERGY SECTOR RISK PROFILE This State Energy Risk Profile examines the relative magnitude of the risks that the State of Maine’s energy infrastructure routinely encounters in comparison with the probable impacts. Natural and man-made hazards with the potential to cause disruption of the energy infrastructure are identified. The Risk Profile highlights risk considerations relating to the electric, petroleum and natural gas infrastructures to become more aware of risks to these energy systems and assets. MAINE STATE FACTS State Overview Annual Energy Production Population: 1.33 million (<1% total U.S.) Electric Power Generation: 14.4 TWh (<1% total U.S.) Housing Units: 0.72 million (1% total U.S.) Coal: 0 TWh, <1% [0.1 GW total capacity] Business Establishments: 0.04 million (1% total U.S.) Petroleum: 0.1 TWh, <1% [1 GW total capacity] Natural Gas: 6 TWh, 42% [1.9 GW total capacity] Nuclear: 0 TWh, 0% [0 GW total capacity] Annual Energy Consumption Hydro: 3.7 TWh, 26% [0.7 GW total capacity] Electric Power: 11.6 TWh (<1% total U.S.) Other Renewable: 0.9 TWh, 6% [1 GW total capacity] Coal: 0 MSTN (0% total U.S.) Natural Gas: 413 Bcf (2% total U.S.) Coal: 0 MSTN (0% total U.S.) Motor Gasoline: 16,100 Mbarrels (1% total U.S.) Natural Gas: 0 Bcf (0% total U.S.) Distillate Fuel: 10,800 Mbarrels (1% total U.S.) Crude Oil: 0 Mbarrels (0% total U.S.) Ethanol: 0 Mbarrels (0% total U.S.) NATURAL HAZARDS OVERVIEW Annual Frequency of Occurrence of Natural Hazards in Maine Annualized Property Loss due to Natural Hazards in Maine (1996–2014) (1996–2014) ❱ According to NOAA, the most common natural hazard in Maine ❱ As reported by NOAA, the natural hazard in Maine that caused the is Thunderstorm & Lightning, which occurs once every 9.5 days greatest overall property loss during 1996 to 2014 is Winter Storm & on the average during the months of March to October. -

DCR's Beaver Brook Reservation

Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection Resource Management Planning Program RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN DCR’s Beaver Brook Reservation Historic Beaver Brook Reservation and Beaver Brook North Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts March 2010 DCR’s Beaver Brook Reservation Historic Beaver Brook Reservation and Beaver Brook North Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2010 Deval L. Patrick, Governor Timothy P. Murray, Lt. Governor Ian A. Bowles, Secretary Richard K. Sullivan, Jr., Commissioner Jack Murray, Deputy Commissioner for Parks Operations The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), an agency of the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, oversees 450,000 acres of parks and forests, beaches, bike trails, watersheds, dams, and parkways. Led by Commissioner Richard K. Sullivan Jr., the agency’s mission is to protect, promote, and enhance our common wealth of natural, cultural, and recreational resources. To learn more about DCR, our facilities, and our programs, please visit www.mass.gov/dcr. Contact us at [email protected]. Printed on Recycled Paper RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN Expanded Beaver Brook Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 Planning Process 2 Distinctive Characteristics of the Expanded Reservation 2 Priority Findings 3 Recommendations 5 Capital Improvements 7 Land Stewardship Zoning Guidelines 9 Management -

COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS SUFFOLK, Ss

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS SUFFOLK, ss SUPERIOR COURT _________________________________________ ) COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS, ) ) STATEMENT OF Plaintiff, ) INTEREST BY THE ) UNITED STATES v. ) ) PENNSYLVANIA HIGHER EDUCATION ) Case No. 1784CV02682 ASSISTANCE AGENCY, ) d/b/a FedLoan Servicing, ) ) Defendant. ) __________________________________________) INTRODUCTION The United States respectfully submits this brief pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 517.1 The United States has a substantial interest in, and a long history of, developing programs to help students access postsecondary education. For decades, the United States has sought to increase access to higher education by serving as a reinsurer and guarantor of private loans, serving as the sole originator and holder of Direct Loans, and also establishing a variety of other federal programs to aid students. Here, Massachusetts alleges that the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA), an entity that contracts with the Federal Government to service federal loans, has violated state and federal consumer protection laws. As relevant here, Massachusetts alleges that PHEAA wrongfully failed to count periods of forbearance for borrowers to satisfy the requirements of certain loan forgiveness programs, that PHEAA 1 “The Solicitor General, or any officer of the Department of Justice, may be sent by the Attorney General to any State or district in the United States to attend to the interests of the United States in a suit pending in a court of the United States, or in a court of a State, or to attend to any other interest of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 517. wrongfully converted the grants of participants who had not filed the correct documentation for loans as required by the Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) Grant Program, and that PHEAA wrongfully allocated certain overpayments to interest and fees. -

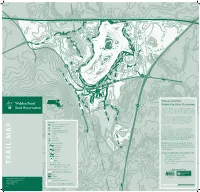

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

The Everyday Life of the Maine Colonists in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 4-1940 The Everyday Life of the Maine Colonists in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Linnea Beatrice Westin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVERYDAY LIFE OF THE MAINE COLONISTS IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES By LINNEA BEATRICE WESTIN A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History College of Arts and Sciences University of Maine Orono April, 1940 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I Introduction, The Background of the Every day Life of the People 1 II The Character of the People 9 III How They Built and Furnished Their• Homes 17 IV The Food They Ate and the Clothes They Wore 29 V Their Customs and Pleasures 38 VI Their Educational Training 48 VII The Religion They Lived 54 VIII The Occupations They Practiced 62 IX Their Crimes and Punishments They Suffered 73 Bibliography 80 140880 PREFACE The everyday life of the colonists who settled in Maine is a field in which very little work has been done as yet* Formerly historians placed the emphasis upon political events and wars; only recently has there been interest taken in all the facts which influence life and make history* The life they lived from day to day, their intel lectual, moral and spiritual aspirations, the houses in which they lived, the food they ate and the clothes they wore, the occupations in which they engaged, their customs and pleasures, are all subjects in which we are in terested, but alas, the material is all too meagre to satisfy our curiosity* The colonial period in Maine is very hazy and much that we would like to know will remain forever hidden under the broad veil of obscurity. -

Ed Muskie, Political Parties, and the Art of Governance

Maine Policy Review Volume 29 Issue 2 Maine's Bicentennial 2020 Ed Muskie, Political Parties, and the Art of Governance Don Nicoll [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Nicoll, Don. "Ed Muskie, Political Parties, and the Art of Governance." Maine Policy Review 29.2 (2020) : 34 -38, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr/vol29/iss2/5. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. ART OF GOVERNANCE Ed Muskie, Political Parties, and the Art of Governance by Don Nicoll creating parties, recreating them, dumping Abstract some and building others, and struggling In its 200-year history as a state, Maine has gone through three major political for power continues today, with credible realignments and is now in the midst of a fourth. The Jefferson Democratic Re- fears about the viability of our representa- publicans supplanted the Federalists to achieve statehood. The Republican Par- tive democracy. ty dominated state politics from the eve of the Civil War until 1954. The Maine The year 2020, the bicentennial of Democratic Party, under the leadership of Edmund S. Muskie and Frank Coffin, the creation of the state of Maine, may be transformed it into a competitive two-party state. Now the goals of open, re- another seminal year in the political life of sponsive, and responsible governance that Muskie and Coffin sought through the United States and the survival of healthy competition and civil discourse are threatened by bitter, dysfunctional representative democracy. -

670 the NEW ENGLAND QUARTERLY Boston, but Class And

670 THE NEW ENGLAND QUARTERLY Boston, but class and status mattered more” and “race determined place in [the] social order” (p. 4). While it is certainly true, as the author demonstrates, that poor whites and persons of color on the margins of society labored together, socialized, and even married— and that the authorities tended to regulate all persons of color as one—perpetual chattel slavery was a unique institution and largely limited to blacks. Perhaps the greatest difficulty is that the book’s ambitions outrun its limited, albeit compelling, sources. Even though relatively short, the book is strikingly repetitive. At that, the author has to reach be- yond Boston in order to fill in the story, a difficulty since one of the book’s theses is that slavery in Boston was different from slavery elsewhere in New England. More significantly, for a book ostensibly framed around eighteenth-century Boston, the book fails to treat in any detail the changes in slave culture that resulted from the spread of revolutionary ideology with its broad message of equality and human rights. Indeed, the book provides only a superficial account—roughly eighteen pages—of the slaves’ transition from meliorative resistance to demands for emancipation in the last quarter of the century and the role of Boston’s black freed people in aiding that change. Nev- ertheless, the book represents a real achievement in adding to our understanding of slavery and the life of slaves in Boston in the first half of the eighteenth century. Marc Arkin is a professor of law at Fordham University. -

Fish Population Sampling

2005 Deerfield River Watershed Fish Population Assessment Robert J. Maietta Watershed Planning Program Worcester, MA January, 2007 CN: 223.4 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ian Bowles, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Arleen O’Donnell, Acting Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Glenn Haas, Acting Assistant Commissioner Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director Introduction Fish population surveys were conducted in the Deerfield River Watershed during the late summer of 2005 using techniques similar to Rapid Bioassessment Protocol V as described originally by Plafkin et al.(1989) and later by Barbour et al. (1999). Standard Operating Procedures are described in MassDEP Method CN 075.1 Fish Population SOP. Surveys also included a habitat assessment component modified from that described in the aforementioned document (Barbour et al. 1999). Fish populations were sampled by electrofishing using a Smith Root Model 12 battery powered backpack electrofisher. A reach of between 80m and 100m was sampled by passing a pole mounted anode ring, side to side through the stream channel and in and around likely fish holding cover. All fish shocked were netted and held in buckets. Sampling proceeded from an obstruction or constriction, upstream to an endpoint at another obstruction or constriction such as a waterfall or shallow riffle. Following completion of a sampling run, all fish were identified to species, measured, and released. Results of the fish population surveys can be found in Table 1. It should be noted that young of the year (yoy) fish from most species, with the exception of salmonids are not targeted for collection. Young-of-the-year fishes which are collected, either on purpose or inadvertently, are noted in Table 1.