A Cruise to the North Channel of Lake Huron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Environment City Greater Sudbury

Physical Environment–Sudbury; OGS Special Volume 6 Selected Headings for Chapter 9, The Past, Present and Future of Sudbury’s Lakes Abstract......................................................................................................................................................... 195 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 195 Geological Control of Sudbury’s Lakes ....................................................................................................... 195 Watersheds and Watershed Units ................................................................................................................. 198 Watersheds in the City ........................................................................................................................... 198 Watershed Units ..................................................................................................................................... 199 Environmental History and Prognosis .......................................................................................................... 199 Pre-Settlement ........................................................................................................................................ 199 The Impact of Industrial Environmental Stresses .................................................................................. 199 Erosion............................................................................................................................................ -

Michigan Study No.: 230703 Project No.: F-80-R-5 Title

STUDY PERFORMANCE REPORT State: Michigan Project No.: F-80-R-5 Study No.: 230703 Title: Lakewide assessment of the contribution of natural recruitment to the chinook salmon population of Lake Huron. Period Covered: October 1, 2003 to September 30, 2004 Study Objective: (1) To estimate annual natural recruitment of chinook salmon to Lake Huron for the 2000 to 2003 year classes; (2) To determine contributions from natural reproduction to the spawning populations of selected tributaries to Lake Huron; (3) To refine recruitment modules of Lake Huron’s bioenergetics and catch-at-age models, which will, in turn, be used to prescribe stocking levels for Lake Huron. Summary: This was the third year of funding for this project. All chinook salmon stocked in lakes Huron and Michigan, except those stocked by Ontario, were marked using oxytetracycline administered in feed. All chinook salmon stocked in Ontario waters of Lake Huron were fin clipped. Quality control samples of vertebrae were received during May and June 2003 from Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin hatcheries and the samples were checked for quality of the oxytetracycline mark. We used ultraviolet microscope equipment and imaging software to enhance reproducibility and specimen processing speed. Vertebrae images and biological data from the Chinook salmon sampled were electronically archived in a database developed cooperatively with Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. These data were shared with other cooperating agencies on the Lake Huron Technical Committee. This year was the third year of field collections and creel clerks and coded-wire tag recovery personnel were trained in gathering vertebrae for the recruitment study. -

The State of Lake Huron in 2010 Special Publication 13-01

THE STATE OF LAKE HURON IN 2010 SPECIAL PUBLICATION 13-01 The Great Lakes Fishery Commission was established by the Convention on Great Lakes Fisheries between Canada and the United States, which was ratified on October 11, 1955. It was organized in April 1956 and assumed its duties as set forth in the Convention on July 1, 1956. The Commission has two major responsibilities: first, develop coordinated programs of research in the Great Lakes, and, on the basis of the findings, recommend measures which will permit the maximum sustained productivity of stocks of fish of common concern; second, formulate and implement a program to eradicate or minimize sea lamprey populations in the Great Lakes. The Commission is also required to publish or authorize the publication of scientific or other information obtained in the performance of its duties. In fulfillment of this requirement the Commission publishes the Technical Report Series, intended for peer-reviewed scientific literature; Special Publications, designed primarily for dissemination of reports produced by working committees of the Commission; and other (non-serial) publications. Technical Reports are most suitable for either interdisciplinary review and synthesis papers of general interest to Great Lakes fisheries researchers, managers, and administrators, or more narrowly focused material with special relevance to a single but important aspect of the Commission's program. Special Publications, being working documents, may evolve with the findings of and charges to a particular committee. Both publications follow the style of the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. Sponsorship of Technical Reports or Special Publications does not necessarily imply that the findings or conclusions contained therein are endorsed by the Commission. -

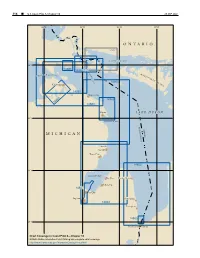

M I C H I G a N O N T a R

314 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 26 SEP 2021 85°W 84°W 83°W 82°W ONTARIO 2251 NORTH CHANNEL 46°N D E 14885 T 14882 O U R M S O F M A C K I N A A I T A C P S T R N I A T O S U S L A I N G I S E 14864 L A N Cheboygan D 14881 Rogers City 14869 14865 14880 Alpena L AKE HURON 45°N THUNDER BAY UNITED ST CANADA MICHIGAN A TES Oscoda Au Sable Tawas City 14862 44°N SAGINAW BAY Bay Port Harbor Beach Sebewaing 14867 Bay City Saginaw Port Sanilac 14863 Lexington 14865 43°N Port Huron Sarnia Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 6—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 ¢ 315 Lake Huron (1) Lawrence, Great Lakes, Lake Winnipeg and Eastern Chart Datum, Lake Huron Arctic for complete information.) (2) Depths and vertical clearances under overhead (12) cables and bridges given in this chapter are referred to Fluctuations of water level Low Water Datum, which for Lake Huron is on elevation (13) The normal elevation of the lake surface varies 577.5 feet (176.0 meters) above mean water level at irregularly from year to year. During the course of each Rimouski, QC, on International Great Lakes Datum 1985 year, the surface is subject to a consistent seasonal rise (IGLD 1985). -

Lake Huron North Channel : Section 6

Lake Huron North Channel : Section 6 p i v R a a er iver l n Rushbrook i Capreol R s h i v Cartier R Val 84 Legend / Légende e i Levack r v 8 Therese e Han awhide a r Waterfront Trail - On-road / Sur la route Washrooms / Washrooms 810 Onaping Lake u P Blezard Valley x r r S o Waterfront Trail - Off-road / Hors route e e 15 r a v Chelmsford Val Ca $ Commercial Area / Zone commerciale v b i i n y Lake ssagi l Wind Waterfront Trail - Gravel road / e aux c R s 86 Route en gravier i Dowling 35 80 Railway Crossing / Passage à niveau a h Azilda P s l i 55 Waterfront Trail - Proposed / Proposée P r n Copper Cliff o 8 a a 1 A Roofed Accommodation / Hébergement avec toiture p 24 v r Fairbank 5 S Alerts / Alertes Quirke k i * n Lively 12 Su Lake c $ Commercial Area / Zone commerciale i 5.0 Distance / Distance (km) Sables a 15 55 l Worthington liot Lake P High Falls 4 Naughton Other Trails - Routes / a Agnew D'autres pistes - Routes Wifi / Wifi 8 r k Lake Turbine Whitefish 42 Whitefish Lake Superior Water Trail / 38 10 Sec 553 Birch L. 17 Lake Sentier maritime du lac Supérieur Restaurants / Restaurants McKerrow 13Nairn Centre McVit Panache Hospital / Hôpital Webbwood Lake Burwa Serpent Chutes HCR Espanola LCBO Liquor Control Board of Ontario / Régie des alcools de l'Ontario River 12 Killarney Lakelands Attraction / Attraction Walford and Headwaters Beach / Plage Border Crossing / Poste de frontière gge Cutler 66 Massey 225 Spanish 53 Sagamok Willisville Parc provincial Campground / Camping Conservation Area / Zone de protection de la nature Killarney -

MARINE NEWS 2. As Mentioned Briefly Last Issue, The

2. MARINE NEWS As mentioned briefly last issue, the sale of the USS Great Lakes Fleet Inc. self-unloaders CALCITE II, MYRON C. TAYLOR and GEORGE A. SLOAN to the Lower Lakes Towing interests was completed on March 31st, thus ensuring the opera ting future of these three venerable vessels that might otherwise have faced nothing but the scrapyard. CALCITE II has been renamed (c) MAUMEE, for the river which serves as Toledo's port; the TAYLOR is now (b) CALUMET, for the Calumet River at Chicago, and the SLOAN is now (b) MISSISSAGI, apparently named in honour of the Mississagi Strait of northern Lake Huron. The three vessels were rechristened in triple ceremonies (the first such in memory) which took place at Sarnia on April 21st. CALUMET's sponsor was Donna Rohn, wife of the president of Grand River Navigation; MAUMEE was christened by Martha Pierson, the wife of Robert Pierson, and MISSISSAGI was sponsored by Judy Kehoe. Following the ceremonies, the fitting out of the three motorships was com pleted, and they look great in Lower Lakes colours. MISSISSAGI is registered at Nanticoke, Ontario, and bears the Lower Lakes Towing Ltd. name on her bows. CALUMET and MAUMEE are registered at Cleveland, and the company name showing on their bows is Lower Lakes Transportation Inc. Interestingly, the first of the ships to enter service was the one whose future was most in doubt before the sale. MAUMEE departed Sarnia on April 28th, bound for Stoneport, and her first cargo took her to Saginaw, where she arrived on the morning of May 1st. -

LAKES of the HURON BASIN: THEIR RECORD of RUNOFF from the LAURENTIDE ICE Sheetq[

Quaterna~ ScienceReviews, Vol. 13, pp. 891-922, 1994. t Pergamon Copyright © 1995 Elsevier Science Ltd. Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved. 0277-3791/94 $26.00 0277-3791 (94)00126-X LAKES OF THE HURON BASIN: THEIR RECORD OF RUNOFF FROM THE LAURENTIDE ICE SHEETq[ C.F. MICHAEL LEWIS,* THEODORE C. MOORE, JR,t~: DAVID K. REA, DAVID L. DETTMAN,$ ALISON M. SMITH§ and LARRY A. MAYERII *Geological Survey of Canada, Box 1006, Dartmouth, N.S., Canada B2 Y 4A2 tCenter for Great Lakes and Aquatic Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. ::Department of Geological Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. §Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, 0H44242, U.S.A. IIDepartment of Geomatics and Survey Engineering, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, N.B., Canada E3B 5A3 Abstract--The 189'000 km2 Hur°n basin is central in the catchment area °f the present Q S R Lanrentian Great Lakes that now drain via the St. Lawrence River to the North Atlantic Ocean. During deglaciation from 21-7.5 ka BP, and owing to the interactions of ice margin positions, crustal rebound and regional topography, this basin was much more widely connected hydrologi- cally, draining by various routes to the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean, and receiving over- ~ flows from lakes impounded north and west of the Great Lakes-Hudson Bay drainage divide. /~ Early ice-marginal lakes formed by impoundment between the Laurentide Ice Sheet and the southern margin of the basin during recessions to interstadial positions at 15.5 and 13.2 ka BE In ~ ~i each of these recessions, lake drainage was initially southward to the Mississippi River and Gulf of ~ Mexico. -

Great Lakes Research Review

Volume 8 2011 Great Lakes Research Review Great Lakes Research Consortium The Saint Lawrence River: Flowing towards Regional Governance Volume 8 2011 Great Lakes Research Review TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to The Saint Lawrence River: Flowing towards Regional Governance Michael R. Twiss, Jeffrey J. Ridal, and Martin Heintzelman .........................................4 A Sustainable Future for the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River Region Rick Findlay ....................................................................................................................5 Governance along the St. Lawrence River: Expanding Beyond Remedial Action Plans Alicia L. Ritcey, Linda M. Campbell, and Jeffrey J. Ridal ...........................................11 The St. Lawrence River Flowing Forward Together Remedial Action Plans for Areas of Concern and Their Role in Saint Lawrence River Governance Katherine Beehler and Jeffrey J. Ridal .........................................................................18 The St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Dam Project: Construction Feat – Economic Failure Claire Puccia Parham ....................................................................................................22 Making the Links: Pollution, Poverty, and Environmental Justice Renee Griffin and Theresa McClenaghan .....................................................................27 The Struggle to Balance Environmental and Economic Interests on the Danube River Suzanne Ebert ...............................................................................................................34 -

Eagle Lake Silver Lake Lawre Lake Jackfish Lake Esox Lak Osb River

98° 97° 96° 95° 94° 93° 92° 91° 90° 89° 88° 87° 86° 85° 84° 83° 82° 81° 80° 79° 78° 77° 76° 75° 74° 73° 72° 71° Natural Resources Canada 56° East r Pen Island CANADA LANDS - ONTARIO e v er i iv R e R ttl k e c K u FIRST NATIONS LANDS AND 56° D k c a l B Hudson Bay NATIONAL PARKS River kibi Nis Produced by the Surveyor General Branch, Geomatics Canada, Natural Resources Canada. Mistahayo ver October 2011 Edition. Spect witan Ri or Lake Lake Pipo To order this product contact: FORT SEVERN I H NDIAN RESERVE Surveyor General Branch, Geomatics Canada, Natural Resources Canada osea Lake NO. 89 Partridge Is land Ontario Client Liaison Unit, Toronto, Ontario, Telephone (416) 973-1010 or r ive E-mail: [email protected] R r e For other related products from the Surveyor General Branch, see website sgb.nrcan.gc.ca v a MA e r 55° N B e I v T i O k k © 2011. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. B R e A e y e e e r r C k C ic p e D s a 55° o r S t turge o on Lak r e B r G e k e k v e a e e v a e e e iv e r r St r r R u e C S C Riv n B r rgeon r d e e o k t v o e v i Scale: 1:2 000 000 or one centimetre equals 20 kilometres S i W t o k s n R i o in e M o u R r 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 kilometres B m berr Wabuk Point i a se y B k v l Goo roo r l g Cape Lookout e e Point e ff h a Flagsta e Cape v r Littl S h i S R S g a Lambert Conformal Conical Projection, Standard Parallels 49° N and 77° N c F Shagamu ta Maria n Henriet r h a Cape i i e g w Lake o iv o h R R n R c ai iv iv Mis Polar Bear Provincial Park E h er e ha r tc r r m ve ua r e a i q v tt N as ve i awa R ey Lake P Ri k NOTE: rne R ee ho se r T e C This map is not to be used for defining boundaries. -

I CAUSES OP the CURRENT in LITTLE CURRENT CHANNEL OP

i CAUSES OP THE CURRENT IN LITTLE CURRENT CHANNEL OP LAKE HURON by WARREN DAVID FORRESTER B.A. The University of Toronto, 191+7 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT S POR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Physics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLOMBIA April," 1961 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (W.D. Forrester) Department of Physics The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 3, Canada. Date April, 1961. ABb2ftACT A current is observed to flow most of the time through Little Current Channel, between North Channel of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. The current varies considerably in its speed, and frequently reverses its direction. Inconvenience is experienc• ed by ships wishing to pass through the narrow and shallow chann el at Little Current, as they must await an opportunity to do so at slack water or on an opposing current. A field survey was carried out during the summer of 1959 in the vicinity of Little Current, Ontario, to determine the cau ses of this current and to ascertain whether or not predictions for the state of the current might be made sufficiently in ad• vance to be of assistance to shipping in the area. -

The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon

The Pilot of La Salle’s Griffon Joe Calnan L’explorateur français Robert Cavelier de La Salle (1643-1687) avait un petit caboteur à voile gréé en barque construit en 1679 pour voyager entre la rivière Niagara et le lac Michigan. La Salle a embauché un pilote qualifié et expérimenté pour mener le navire sur ces eaux, mais en moins de neuf mois suivant le début de son emploi sur les Grands Lacs, le pilote avait perdu deux barques qui lui ont été confiées et a disparu avec l’équipage entier. La perte du Griffon de La Salle a été chroniqué par le missionnaire récollet Louis Hennepin, et est devenu l’un des grands mystères des Grands Lacs . Aujourd’hui, le pilote a acquis une notoriété comme un grand hérétique danois, de mauvaise humeur, grand de sept pieds, nommé Luke Dare; mais si ce personnage a son fondement dans les sources primaires ou dans le folklore n’a jamais été clairement établi. En examinant systématiquement les origines de l'information que nous avons sur le pilote dans les documents autant primaires que secondaires, le présent article tente de séparer le folklore des sources vérifiables et mettre en lumière une image plus précise du pilote du Griffon de La Salle. At the ship’s helm was an odd sort of character. Standing seven feet tall, Luke the Dane was known for his violent temper and an attitude that spoke “does not work well with others.” Yet he was a good pilot and was needed if the Griffon was to be a success.1 We saw near the village of Matchinkoa a tree from which the bark had been removed three or four years ago, and on which was depicted a man with a tapabord hat pulled down below his ears, a grey justaucorps, breeches, short legs, a big beard, and a gun in his hand, another figure near him, tied up like a slave, and four scalps.2 When Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle was given permission by Louis XIV to 1 Colleen Burcar, It Happened in Michigan: Remarkable Events That Shaped History (Guilford, 2010), 8. -

Ontario History Scholarly Journal of the Ontario Historical Society Since 1899

Ontario History Scholarly Journal of The Ontario Historical Society Since 1899 Papers and Records [called Ontario History after 1946] Volume XI, 1913 Published by The Ontario Historical Society, 1913 The Ontario Historical Society Established in 1888, the OHS is a non-profit corporation and registered charity; a non- government group bringing together people of all ages, all walks of life and all cultural backgrounds interested in preserving some aspect of Ontario's history. Learn more at www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca. ®ntario 1DistoricaI Society PAPERS AND RECORDS TORONTO PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY 1913 (lDntarin fiiatnriral Svnrivtg. PAPERS AND RECORDS VOL. X1. TORONTO: PUBLISHED BY THE SOCKET‘! I913 OFFICERS, 1912,13 President Honorary : THE HONORABLE THE MINISTER or EDUCATION or ONTARIQ. President : JOHN i)EARNEss, M.A., London. lst Vice'President: CLARANCE M. WARNER, Napanee. i Vice’ President 2nd : SIR EDMUND WALKER, Toronto ; Secretary and Acting Treasurer: ALEXANDER FRASER, LL.D., LiTT. D., Toronto. Auditors : J. J. MURPHY, Toronto. FRANK YEIGH, Toronto Councillors : A. F. HUNTER, M.A. W. STEWART WALLACE. B.A. J. STE-‘.\\'ART CARSTAIRS, B.A. W. L. GRANT, M.A. ALEXANDER FRAsER, LL.D.. LXTT. D.. F.S.A., SCOT. (Edin.) The Ontario Historical Society does not a:~sume 1'espu11sibilit)' for the statements of its contributors. Place/Names in Georgian Bay (Including the North Channel) BY JAMES WHITE, F.R.G.S. For convenience and on account Of the historical connection, the North Channel names have also been included in this compila- tion. Place—names in the area covered by this paper can be assigned to three distinct periods first.