The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue …

In This Issue … INLAND SEAS®VOLUME 72 WINTER 2016 NUMBER 4 MAUMEE VALLEY COMES HOME . 290 by Christopher H. Gillcrist KEEPING IT IN TRIM: BALLAST AND GREAT LAKES SHIPPING . 292 by Matthew Daley, Grand Valley State University Jeffrey L. Ram, Wayne State University RUNNING OUT OF STEAM, NOTES AND OBSERVATIONS FROM THE SS HERBERT C. JACKSON . 319 by Patrick D. Lapinski NATIONAL RECREATION AREAS AND THE CREATION OF PICTURED ROCKS NATIONAL LAKESHORE . 344 by Kathy S. Mason BOOKS . 354 GREAT LAKES NEWS . 356 by Greg Rudnick MUSEUM COLUMN . 374 by Carrie Sowden 289 KEEPING IT IN TRIM: BALLAST AND GREAT LAKES SHIPPING by Matthew Daley, Grand Valley State University Jeffrey L. Ram, Wayne State University n the morning of July 24, 1915, hundreds of employees of the West- Oern Electric Company and their families boarded the passenger steamship Eastland for a day trip to Michigan City, Indiana. Built in 1903, this twin screw, steel hulled steamship was considered a fast boat on her regular run. Yet throughout her service life, her design revealed a series of problems with stability. Additionally, changes such as more lifeboats in the aftermath of the Titanic disaster, repositioning of engines, and alterations to her upper cabins, made these built-in issues far worse. These failings would come to a disastrous head at the dock on the Chicago River. With over 2,500 passengers aboard, the ship heeled back and forth as the chief engineer struggled to control the ship’s stability and failed. At 7:30 a.m., the Eastland heeled to port, coming to rest on the river bottom, trapping pas- sengers inside the hull and throwing many more into the river. -

Native American Context Statement and Reconnaissance Level Survey Supplement

NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for The City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning & Economic Development Prepared by Two Pines Resource Group, LLC FINAL July 2016 Cover Image Indian Tepees on the Site of Bridge Square with the John H. Stevens House, 1852 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 583) Minneapolis Pow Wow, 1951 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 35609) Minneapolis American Indian Center 1530 E Franklin Avenue NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development 250 South 4th Street Room 300, Public Service Center Minneapolis, MN 55415 Prepared by Eva B. Terrell, M.A. and Michelle M. Terrell, Ph.D., RPA Two Pines Resource Group, LLC 17711 260th Street Shafer, MN 55074 FINAL July 2016 MINNEAPOLIS NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT This project is funded by the City of Minneapolis and with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. -

The Lure of Niagara

The Lure of Niagara Highlights from the Charles Rand Penney Historical Niagara Falls Print Collection 1 3 Arthur Lumley (Irish, 1837-1912), Niagara Seen with Different Eyes from Harper’s Weekly (detail), 1873, wood engraving, 13 ⁄2 x20 ⁄8 in. Robert Hancock (English, 1730-1817), The Waterfall of Niagara—La Cascade de Niagara , 1 1 1794, engraving with hand color, 9 ⁄4x 15 ⁄4 in. Asa Smith (American), View of the Meteoric Shower, as seen at Niagara Falls on the Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826-1900), The Great Fall—Niagara , 1875, 5 Night of the 12th and 13th of November , 1833 from Smith's Illustrated Astronomy, chromolithograph with hand color, 16 ⁄8 x 36 in. Designed for the use of the Public or Common Schools in the United States , 1863, 1 1 wood engraving, 11 ⁄4 x 9 ⁄2 in. IntroTdheu Cchtairolen s Rand Penney Collection of Historical It is believed that more prints were made of Niagara Falls before Niagara Falls Prints the twentieth century than of any other specific place, and the Charles Rand Penney Collection of Historical Niagara Falls Prints The Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University acquired the Charles Rand is one of the largest collections of this genre. Viewing so many Penney Collection of Historical Niagara Falls Prints in 2006. This collection, images of one subject together, we can gain new insights not only a generous donation from Dr. Charles Rand Penney, was partially funded by about the location itself, but also about the manner in which the the Castellani Purchase Fund, with additional funding from Mr. -

Applicant's Environmental Report –

Prairie Island Nuclear Generating Plant License Renewal Application Appendix E - Environmental Report Applicant’s Environmental Report – Operating License Renewal Stage Prairie Island Nuclear Generating Plant Nuclear Management Company, LLC Units 1 and 2 Docket Nos. 50-282 and 50-306 License Nos. DPR-42 and DPR-60 April 2008 Prairie Island Nuclear Generating Plant License Renewal Application Appendix E - Environmental Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.................................................................... xi 1.0 PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION ................................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction and Background........................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Statement of Purpose and Need .................................................................. 1-2 1.3 Environmental Report Scope and Methodology ........................................... 1-3 1.4 Prairie Island Nuclear Generating Plant Licensee and Ownership ............... 1-4 1.5 References ................................................................................................ 1-7 2.0 SITE AND ENVIRONMENTAL INTERFACES............................................. 2-1 2.1 General Site Description............................................................................... 2-1 2.1.1 Regional Features and General Features in the 6-Mile Vicinity............................................................................................. 2-2 2.1.2 PINGP Site Features...................................................................... -

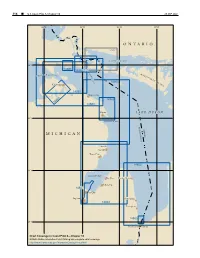

M I C H I G a N O N T a R

314 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 26 SEP 2021 85°W 84°W 83°W 82°W ONTARIO 2251 NORTH CHANNEL 46°N D E 14885 T 14882 O U R M S O F M A C K I N A A I T A C P S T R N I A T O S U S L A I N G I S E 14864 L A N Cheboygan D 14881 Rogers City 14869 14865 14880 Alpena L AKE HURON 45°N THUNDER BAY UNITED ST CANADA MICHIGAN A TES Oscoda Au Sable Tawas City 14862 44°N SAGINAW BAY Bay Port Harbor Beach Sebewaing 14867 Bay City Saginaw Port Sanilac 14863 Lexington 14865 43°N Port Huron Sarnia Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 6—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 ¢ 315 Lake Huron (1) Lawrence, Great Lakes, Lake Winnipeg and Eastern Chart Datum, Lake Huron Arctic for complete information.) (2) Depths and vertical clearances under overhead (12) cables and bridges given in this chapter are referred to Fluctuations of water level Low Water Datum, which for Lake Huron is on elevation (13) The normal elevation of the lake surface varies 577.5 feet (176.0 meters) above mean water level at irregularly from year to year. During the course of each Rimouski, QC, on International Great Lakes Datum 1985 year, the surface is subject to a consistent seasonal rise (IGLD 1985). -

Portrayals of Hennepin

Portrayals of Hennepin "Discoverer" of the Falls of St. Anthony, 1680 Patricia Condon Jofinston IT HAS BEEN 300 years since Father Louis Hennepin, souls. To boot, he struggled with a seemingly insatiable one of the most controversial of explorers, "discovered " appetite for adventure. Because of this last, and his flair the Falls of St. Anthony. The story is an oft-repeated as a publicist, but also owing to fortuitous circumstances one. Hennepin himself told it first when he published — by chance, he happened to be in the right place first Description of Louisiana in Paris in 1683. Much to his — he is one of the best-remembered personages of the discredit, though, he also told it a second time and more. seventeenth century. Artists have contributed minimally These later editions of his travels were an incredible to his fame, too (of which more later), although there is no embroidery.' superabundance of depictions of him and his exploits. There seems to be no reason to doubt the piety of the Almost nothing is known of Hennepin's early life. stern-faced, straitlaced cleric. He evidently made a good Most historians agree that he was probably born and missionary, with a main concern for saving heathen baptized at Ath, Belgium, in 1640. At the age of about twenty, in France, he took the gray-cowled habit of the 'Concerning Father Hennepin in this paragraph and sev Recoflect fathers, mendicant preachers who belonged to eral following, the author consulted Father Louis Hennejiin, Description of Louisiana (Minneapolis, 1938), translated by the Franciscan order. In 1675, in the company of four Marion E. -

MARINE NEWS 2. As Mentioned Briefly Last Issue, The

2. MARINE NEWS As mentioned briefly last issue, the sale of the USS Great Lakes Fleet Inc. self-unloaders CALCITE II, MYRON C. TAYLOR and GEORGE A. SLOAN to the Lower Lakes Towing interests was completed on March 31st, thus ensuring the opera ting future of these three venerable vessels that might otherwise have faced nothing but the scrapyard. CALCITE II has been renamed (c) MAUMEE, for the river which serves as Toledo's port; the TAYLOR is now (b) CALUMET, for the Calumet River at Chicago, and the SLOAN is now (b) MISSISSAGI, apparently named in honour of the Mississagi Strait of northern Lake Huron. The three vessels were rechristened in triple ceremonies (the first such in memory) which took place at Sarnia on April 21st. CALUMET's sponsor was Donna Rohn, wife of the president of Grand River Navigation; MAUMEE was christened by Martha Pierson, the wife of Robert Pierson, and MISSISSAGI was sponsored by Judy Kehoe. Following the ceremonies, the fitting out of the three motorships was com pleted, and they look great in Lower Lakes colours. MISSISSAGI is registered at Nanticoke, Ontario, and bears the Lower Lakes Towing Ltd. name on her bows. CALUMET and MAUMEE are registered at Cleveland, and the company name showing on their bows is Lower Lakes Transportation Inc. Interestingly, the first of the ships to enter service was the one whose future was most in doubt before the sale. MAUMEE departed Sarnia on April 28th, bound for Stoneport, and her first cargo took her to Saginaw, where she arrived on the morning of May 1st. -

Download Download

2016. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 125(2):151–157 131ST ANNUAL ACADEMY MEETING1 Presidential Plenary Address by Michael A. Homoya2 ‘‘INDIANA 1816 – CONNECTING WITH OUR PAST,PRESERVING FOR OUR FUTURE’’ Although some text has been added, the following This year, 2016, is Indiana’s bicentennial, and I generally adheres to the outline and content of would like to return to the topic, to remember a Michael Homoya’s presidential address given at the land of vast forests, expansive wetlands, clear 131st Annual Academy Meeting held in Indianapolis flowing waterways and lakes, and prairies stretch- on March 26, 2016. Citations have been added. ing across the horizon as far as the eye could see; to remember a time when herds of bison traveled INTRODUCTION ancient paths, passenger pigeons darkened the In 1916 the annual meeting of the Indiana skies, and wolves, bears and panthers roamed the Academy of Science (IAS) occurred during the land. centennial anniversary of Indiana’s statehood. The Join me as we turn the clock back more than 300 IAS president reported on the general advance- years and begin with what may be the earliest first- ments in science that had occurred worldwide person written account of Indiana’s landscape. (Bigney 1917), while others addressed advance- THE FRENCH CONNECTION ments made in Indiana during the previous 100 years, e.g., Evermann (1917) and Coulter (1917) on In December 1679, while traveling in a canoe zoology and botany, respectively. They all make with La Salle and othersdownthe Kankakee River, for interesting reading, but it was a presentation Fr. -

LAKES of the HURON BASIN: THEIR RECORD of RUNOFF from the LAURENTIDE ICE Sheetq[

Quaterna~ ScienceReviews, Vol. 13, pp. 891-922, 1994. t Pergamon Copyright © 1995 Elsevier Science Ltd. Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved. 0277-3791/94 $26.00 0277-3791 (94)00126-X LAKES OF THE HURON BASIN: THEIR RECORD OF RUNOFF FROM THE LAURENTIDE ICE SHEETq[ C.F. MICHAEL LEWIS,* THEODORE C. MOORE, JR,t~: DAVID K. REA, DAVID L. DETTMAN,$ ALISON M. SMITH§ and LARRY A. MAYERII *Geological Survey of Canada, Box 1006, Dartmouth, N.S., Canada B2 Y 4A2 tCenter for Great Lakes and Aquatic Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. ::Department of Geological Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. §Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, 0H44242, U.S.A. IIDepartment of Geomatics and Survey Engineering, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, N.B., Canada E3B 5A3 Abstract--The 189'000 km2 Hur°n basin is central in the catchment area °f the present Q S R Lanrentian Great Lakes that now drain via the St. Lawrence River to the North Atlantic Ocean. During deglaciation from 21-7.5 ka BP, and owing to the interactions of ice margin positions, crustal rebound and regional topography, this basin was much more widely connected hydrologi- cally, draining by various routes to the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean, and receiving over- ~ flows from lakes impounded north and west of the Great Lakes-Hudson Bay drainage divide. /~ Early ice-marginal lakes formed by impoundment between the Laurentide Ice Sheet and the southern margin of the basin during recessions to interstadial positions at 15.5 and 13.2 ka BE In ~ ~i each of these recessions, lake drainage was initially southward to the Mississippi River and Gulf of ~ Mexico. -

On the Hennepin Trail

ON THE HENNEPIN TRAIL^ Of the city of Ath, in the province of Hainault, Belgium, Baedeker says that it is an ancient town but that " it need not detain the tourist long." Baedeker, however, when he made this statement evidently did not have several days on his hands before the steamer sailed from Cherbourg, nor above all did he have the reverential attitude that all dwellers by the Falls of St. Anthony of Padua in the New World ought to have toward Ath as the birthplace of Father Louis Hennepin. In point of fact Baedeker does not mention Hennepin at all. And yet the famous missionary adventurer is not without honor in his own country, as will shortly be seen. Ath has a population of about ten thousand and carries on some little commercial and manufacturing business with the outside world. It is one of those tightly built little towns of narrow streets that one sees everywhere in Belgium; withal a pleasant little city in an equally pleasant setting of gently rolling and carefully cultivated country. Like so many cities in the low countries it has its canal connecting it commercially with the outside world. Its little river, in this case the Dendre, flowing in stretches through walled banks, gives the city a decidedly picturesque air. An occasional pair of wooden shoes rattles along over the cobblestone pavement. There is an ancient church or two, a donjon tower constructed by a cer tain count of Hainault at some time in the remote past, and the usual market place or " cloth market" where on certain days you can bargain with tight-fisted old women for the produce of the country and relieve your ensuing exhaustion at some one of the numerous cafes which line the square. -

Eagle Lake Silver Lake Lawre Lake Jackfish Lake Esox Lak Osb River

98° 97° 96° 95° 94° 93° 92° 91° 90° 89° 88° 87° 86° 85° 84° 83° 82° 81° 80° 79° 78° 77° 76° 75° 74° 73° 72° 71° Natural Resources Canada 56° East r Pen Island CANADA LANDS - ONTARIO e v er i iv R e R ttl k e c K u FIRST NATIONS LANDS AND 56° D k c a l B Hudson Bay NATIONAL PARKS River kibi Nis Produced by the Surveyor General Branch, Geomatics Canada, Natural Resources Canada. Mistahayo ver October 2011 Edition. Spect witan Ri or Lake Lake Pipo To order this product contact: FORT SEVERN I H NDIAN RESERVE Surveyor General Branch, Geomatics Canada, Natural Resources Canada osea Lake NO. 89 Partridge Is land Ontario Client Liaison Unit, Toronto, Ontario, Telephone (416) 973-1010 or r ive E-mail: [email protected] R r e For other related products from the Surveyor General Branch, see website sgb.nrcan.gc.ca v a MA e r 55° N B e I v T i O k k © 2011. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. B R e A e y e e e r r C k C ic p e D s a 55° o r S t turge o on Lak r e B r G e k e k v e a e e v a e e e iv e r r St r r R u e C S C Riv n B r rgeon r d e e o k t v o e v i Scale: 1:2 000 000 or one centimetre equals 20 kilometres S i W t o k s n R i o in e M o u R r 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 kilometres B m berr Wabuk Point i a se y B k v l Goo roo r l g Cape Lookout e e Point e ff h a Flagsta e Cape v r Littl S h i S R S g a Lambert Conformal Conical Projection, Standard Parallels 49° N and 77° N c F Shagamu ta Maria n Henriet r h a Cape i i e g w Lake o iv o h R R n R c ai iv iv Mis Polar Bear Provincial Park E h er e ha r tc r r m ve ua r e a i q v tt N as ve i awa R ey Lake P Ri k NOTE: rne R ee ho se r T e C This map is not to be used for defining boundaries. -

Father Louis Hennepin, Belgian

FATHER LOUIS HENNEPIN, 1694 - [From an oil painting by an unknown artist in the museum of the Minn^ sota Historical Society.] FATHER LOUIS HENNEPIN, BELGIAN' It is extremely gratifying to me and to every Belgian to find that the memory of our compatriot, Father Louis Henne pin, is revered and the history of his achievements commemo rated here on the spot where he made the great discovery of the falls which he named in honor of St. Anthony of Padua. I want to thank you, not only on my own behalf, but also on behalf of the Belgian nation for this splendid tribute to the memory of our feUow countryman. And, although I have received no special message from the spirit world, I am con fident that the good Father Hennepin himself must look down with satisfaction upon this scene and that he is gratified to know that his great exploit is not forgotten by those who followed in his footsteps and who have built a great metropolis where he found a primeval forest. Although I have no direct communication from Father Hen nepin, I have here a message, which I will now read to you, from his fellow townsmen and from the mayor of Ath, where he was born: ADMINISTRATION OF THE COMMUNE OF ATH ATH, September 20th, 1930 To HIS HIGHNESS THE PRINCE ALBERT DE LIGNE, BELGIAN AMBASSADOR, WASHINGTON. HIGHNESS: The population of Ath has been deeply gratified to learn that the City of Minneapolis proposes to celebrate, on the 12th day of October next, the 250th Anniversary of the Discovery of the Falls of the Mississippi by a son of Ath, the Father Hennepin.