History of Self Research - 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applications of Buddhist Philosophy in Psychotherapy

Psychology | Research The Self and the Non-Self: Applications of Buddhist Philosophy in Psychotherapy Contributed by William Van Gordon, Edo Shonin, and Mark D. Griffiths Division of Psychology, Nottingham Trent University Psychological approaches to treating mental illness or improving psychological wellbeing are invariably based on the explicit or implicit understanding that there is an intrinsically existing ‘self’ or ‘I’ entity. In other words, regardless of whether a cognitive-behavioural, psychodynamic, or humanistic psychotherapy treatment model is employed, these approaches are ultimately concerned with changing how the ‘I’ relates to its thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, and/or to its physical, social, and spiritual environment. Although each of these psychotherapeutic modalities have been shown to have utility for improving psychological health, there are inevitably limitations to their effectiveness and there will always be those individuals for whom they are incompatible. Given such limitations, research continuously attempts to identify and empirically validate more effective, acceptable and/or diverse treatment approaches. One such approach gaining momentum is the use of techniques that derive from Buddhist contemplative practice. Although mindfulness is arguably the most popular and empirically researched example, there is also growing interest into the psychotherapeutic applications of Buddhism’s ‘non-self’ ontological standpoint (in which ontology is basically the philosophical study of the nature or essence of being, existence, or reality). Within Buddhism, the term ‘non-self’ refers to the realisation that the ‘self’ or the ‘I’ is absent of inherent existence. On first inspection, this might seem to be a somewhat abstract concept but it is actually common sense and the principle of ‘non-self’ is universal in its application. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Chapter 02 Who Am I?

January 8, 2013 at 10:30 AM 452_chapter_02.docx page 1 of 52 CHAPTER 02 WHO AM I? I. WHO AM I? ...................................................................................................................................... 3 A. THREE COMPONENTS OF THE EMPIRICAL SELF (OR ME) ............................................................................. 4 B. EXTENSIONS AND REFINEMENTS OF JAMES’S THEORY ................................................................................ 9 II. SELF-FEELING, SELF-SEEKING, AND SELF-PRESERVATION ............................................................... 14 A. SELF-FEELINGS AS BASIC EMOTIONS ..................................................................................................... 15 B. SELF-CONSCIOUS EMOTIONS .............................................................................................................. 15 C. SELF-FEELINGS AND SELF-STANDARDS .................................................................................................. 17 D. SELF-FEELINGS AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS ........................................................................................... 20 E. SUMMARY AND SYNTHESIS ................................................................................................................. 21 III. GROUP DIFFERENCES IN THE SELF-CONCEPT .................................................................................. 21 A. CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN THE SELF-CONCEPT ..................................................................................... -

Summer 2013 Section B01 Syllabus

George Mason University College of Education and Human Development Secondary Education Program EDUC 672 Human Development and Learning: Secondary Education Summer 2013 Instructor: David Vallett, PhD Day and Time: Tuesday and Thursday 4:30-7:10 Class Location: Robinson A 412 Telephone: 910 352 8275 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By appointment Required Textbooks: Snowman, J., & MCCown, R. (2013). Educational psychology. Wadsworth, Cengage Publishing. (This is an interactive e-book that includes video cases and auto-graded quizzes among other online supports.) Other articles and handouts will be distributed during class or posted on-line on Bb. The site for our course is at http://mymasonportal.gmu.edu. Course Description Education 672 explores the processes that influence the intellectual, social, emotional and physical development of middle and high school students. Within that context, the course further examines the processes and theories that provide a basis for understanding the learning process. Particular attention is given to constructivist theories and practices of learning, the role of symbolic competence as a mediator of learning, understanding, and knowing, and the facilitation of critical thinking and problem solving. Processes of developing and learning are considered as they impact the design of instruction and the selection of curriculum. The course also explores the relation of theories of learning to the construction of learning environments, student motivation, classroom management, assessment and how technology supports teaching and learning. Course Methodology The course is structured around readings, case analyses, reflections on those readings, conceptual analyses of developmental psychology and learning theories, expert group projects, a review of current research, and technology activities in a seminar format. -

HERBERT ROSENFELD This Article Was First Published in 1971 in P

HERBERT ROSENFELD This article was first published in 1971 in P. Doucet and C. Laurin (eds) Problems of Psychosis, The Hague: Exceqita Medica, 115-28. Following the suggestion of the organizers of the Symposium that I should discuss the importance of projective identification and ego splitting in the psychopathology of the psychotic patient, I shall attempt to give you a survey of the processes described under the term: 'projective identification'. I shall first define the meaning of the term 'projective identification' and quote from the work of Melanie Klein, as it was she who developed the concept. Then I shall go on to discuss very briefly the work of two other writers whose use appeared to be related to, but not identical with, Melanie Klein's use of the term. 'Projective identification' relates first of all to a splitting process of the early ego, where either good or bad parts of the self are split off from the ego and arc as a further step projected in love or hatred into external objects whi~h leads to fusion and identification of the projected parts of the self with the external objects. There are important paranoid anxieties related to these processes as the objects filled with aggressive parts of the self become persecuting and are experienced by the patient as threatening to retaliate by forcing themselves and the bad parts of the self which they contain back again into the ego. In her paper on schizoid mechanisms Melanie IKlein (1946j considers first of all the importance of the processes of splitting and 117 Melanie Klein Today: Projective Identification denial and omnipotence which during the early phase of develop ment play a role similar to that of repression at a later stage of ego development. -

PERSONAL and SOCIAL IDENTITY: SELF and SOCIAL CONTEXT John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, S. Alexander Haslam and Craig Mcgarty D

PERSONAL AND SOCIAL IDENTITY: SELF AND SOCIAL CONTEXT John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, S. Alexander Haslam and Craig McGarty Department of Psychology Australian National University Paper presented to the Conference on "The Self and the Collective" Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, 7-10 May 1992 A revised version of this paper will appear in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Special Issue on The Self and the Collective Professor J. C. Turner Department of Psychology GPO Box 4, ANU Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia Tel: 06 249 3094 Fax: 06 249 0499 Email: [email protected] 30 April 1992 2 Abstract Social identity and self-categorization theories provide a distinctive perspective on the relationship between the self and the collective. They assume that individuals can and do act as both individual persons and social groups and that, since both individuals and social groups exist objectively, both personal and social categorical self-categorizations provide valid representations of self in differing social contexts. As social psychological theories of collective behaviour, they take for granted that they cannot provide a complete explanation of the concrete social realities of collective life. They define their task as providing an analysis of the psychological processes that interact with and make possible the distinctive "group facts" of social life. From the early 1970s, beginning with Tajfel's research on social categorization and intergroup discrimination, social identity theory has explored the links between the self- evaluative aspects of social'identity and intergroup conflict. Self-categorization theory, emerging from social identity research in the late 1970s, made a basic distinction between personal and social identity as differing levels of inclusiveness in self-categorization and sought to show how the emergent, higher-order properties of group processes could be explained in terms of a functional shift in self-perception from personal to social identity. -

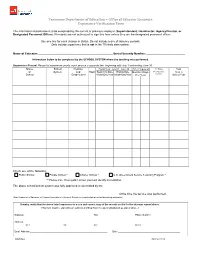

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

The Development of Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales For

Gilbert et al. Journal of Compassionate Health Care (2017) 4:4 DOI 10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Open Access The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others Paul Gilbert1*, Francisca Catarino2, Cristiana Duarte3, Marcela Matos3, Russell Kolts4, James Stubbs5, Laura Ceresatto6, Joana Duarte3, José Pinto-Gouveia3 and Jaskaran Basran1 Abstract Background: Studies of the value of compassion on physical and mental health and social relationships have proliferated in the last 25 years. Although, there are several conceptualisations and measures of compassion, this study develops three new measures of compassion competencies derived from an evolutionary, motivational approach. The scales assess 1. the compassion we experience for others, 2. the compassion we experience from others, and 3. self-compassion based on a standard definition of compassion as a ‘sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it’. We explored these in relationship to other compassion scales, self-criticism, depression, anxiety, stress and well-being. Methods: Participants from three different countries (UK, Portugal and USA) completed a range of scales including compassion for others, self-compassion, self-criticism, shame, depression, anxiety and stress with the newly developed ‘The Compassionate Engagement and Actions’ scale. Results: All three scales have good validity. Interestingly, we found that the three orientations of compassion are only moderately correlated to one another (r < .5). We also found that some elements of self-compassion (e.g., being sensitive to, and moved by one’s suffering) have a complex relationship with other attributes of compassion (e.g., empathy), and with depression, anxiety and stress. -

Selected Books, Articles, and Monographs for the Guidance Of

Dnet,MFti R F SUMF CG 002 982 ED 023 121 24 By -McGuire, Carson Behavioral Science Memorandum Number10. Texas Univ., Austin. Research andDevelopment Center for TeacherEducation. Spons Agency -Office of Education(DHEW), Washington, D C. Report No -BSR -M -10 Bureau No -BR -5 -0249 Pub Date 66 Contract -OEC -6 -10 -108 Note -36p.; Includes Addenda toBehavioral Science MemorandumNumber 10. EDRS Price MF -$025 HC -$190 Development, *Teacher Education Descriptors -*Annotated Bibliographies,*Child Development, *Human Number 10 was theinitial venture intoannotating Behavioral Science Memorandum of busy instructors selected books, articles,and monographsfor the guidance responsible for teacher education.The responses to theannotated bibliographies Apparently some sortof handbook forlearning throughguided have been positive. teacher discovery is a possible meansof orienting collegeprofessors and students in education to the realizationthat the mafor objective inthe educational encounter is regurgitation" in examinationsbut the not "soaking vp"information for later "selective information as it intellectual capabilities necessaryto relate new acquisition of the annotated entries) develops to theunderlying principles of afield study. (137 (AUTHOR) via_57-0.240 EDUCATION RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENTCENTER TN TEAChTH THE UNIVERSITY OFTEXAS Behavioral ScienceMemorandum No. 10 July, 1966 S.H. 308 Bibliographies other Child and HumanDevelopment and the The two bibliographies in thismemorandum, one on and literature. They point to books on Human Development andEducation, merely sample the well as some tiresomereading. What the journals which provide many ideasand explanations, as be of interest toother persons. writer regards as "tiresome" orirrelevant, of course, may IMPORTANT NOTE without much writtenfeedback. The A number of memoranda and aNewsletter have been issued from our readers. -

Four Perspectives

Educational Psychology important notes Theories about human learning can be grouped into four broad "perspectives". These are Behaviorism - focus on observable behavior Cognitive - learning as purely a mental/ neurological process Humanistic - emotions and affect play a role in learning Social - humans learn best in group activities The development of these theories over many decades is a fascinating story. Some theories developed as a negative reaction to earlier ones. Others built upon foundational theories, looking at specific contexts for learning, or taking them to a more sophisticated level. There is also information here about general theories of learning, memory, and instructional methodology. Read brief descriptions of these four general perspectives here: Learning www.allonlinefree.comTheories: Four Perspectives Within each "perspective" listed below, there may be more than one cluster of theories. Click on the name of the theorist to go to the page with biographical information and a description of the key elements of his/her theory. www.allonlinefree.com Educational Psychology important notes 1. Behaviorist Perspective Classical Conditioning: Stimulus/Response Ivan Pavlov 1849-1936 Classical Conditioning Theory Behaviorism: Stimulus, Response, Reinforcement John B. Watson 1878-1958 Behaviorism Edward L. Thorndike 1874-1949 Connectivism Edwin Guthrie 1886-1959 Contiguity Theory B. F. Skinner 1904-1990 Operant Conditioning William Kaye Estes 1919 - Stimulus Sampling Theory Neo-behaviorism: Stimulus-Response; Intervening Internal -

A Critical Examination of the Theoretical and Empirical Overlap Between Overt Narcissism and Male Narcissism and Between Covert Narcissism and Female Narcissism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Smith College: Smith ScholarWorks Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2009 A critical examination of the theoretical and empirical overlap between overt narcissism and male narcissism and between covert narcissism and female narcissism Lydia Onofrei Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Onofrei, Lydia, "A critical examination of the theoretical and empirical overlap between overt narcissism and male narcissism and between covert narcissism and female narcissism" (2009). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1133 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lydia Onofrei A Critical Examination of the Theoretical and Empirical Overlap Between Overt Narcissism and Male Narcissism, and Between Covert Narcissism and Female Narcissism ABSTRACT Within the past twenty years, there has been a proliferation of empirical research seeking to distinguish between overt and covert types of narcissism and to elucidate the differences between narcissistic pathology among men and women, yet these two areas of research have largely been carried out independently of one another in spite of clinical observations suggesting a relationship between them. This project was undertaken to systematically examine whether an overlap exists between the clinical category of overt narcissism and male/masculine narcissism, or between the category of covert narcissism and female/feminine narcissism. Secondly, it sought to elaborate on areas of overlap between these categories. -

Final Thesis Shahram Rafieian Koupaei.Pdf

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dissociation, unconscious and social theory : towards an embodied relational sociology Rafieian Koupaei, Shahram Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Dissociation, unconscious and social theory towards an embodied relational sociology Thesis submitted for examination for: PhD in Sociology and Social Policy Shahram Rafieian koupaei School of Social Sciences Bangor University 2015 I hereby declare that (i) the thesis is not one for which a degree has been or will be conferred by any other university or institution; (ii) the thesis is not one for which a degree has already been conferred by this University; (iii) the work for the thesis is my own work and that, where material submitted by me for another degree or work undertaken by me as part of a research group has been incorporated into the thesis, the extent of the work thus incorporated has been clearly indicated.