SO 003 019 State Univ. of New York, Stony Brook. American the Occasional Paper Is Intended As a Resource Document and Is Designe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinaâ•Žs Cultural Revolution and How the Red Guard

University of Portland Pilot Scholars History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations History 12-2020 The Kids Aren’t Alright: China’s cultural revolution and how the Red Guard impacted family Lillian Healy Follow this and additional works at: https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Chinese Studies Commons Citation: Pilot Scholars Version (Modified MLA Style) Healy, Lillian, "The Kids Aren’t Alright: China’s cultural revolution and how the Red Guard impacted family" (2020). History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations. 32. https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs/32 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Pilot Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Pilot Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Kids Aren’t Alright: China’s cultural revolution and how the Red Guard impacted family By Lillian Healy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History University of Portland December 2020 When talking about the younger generation, many people think about their potential to change the world. As evident by modern social and political issues, young people are more likely to advocate for change. From social media platforms to protests, youth have become increasingly involved due to the information age that we live in. The narrative that kids receive is important, as how children are raised will impact what kind of person they will be. Whether its college students advocating for equal rights or younger students protesting for gun safety regulations, the world view children are exposed to will impact how they think and what they believe in. -

THE SECURITISATION of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract

ПОЛИТИКОЛОГИЈА РЕЛИГИЈЕ бр. 2/2012 год VI • POLITICS AND RELIGION • POLITOLOGIE DES RELIGIONS • Nº 2/2012 Vol. VI ___________________________________________________________________________ Tsering Topgyal 1 Прегледни рад Royal Holloway University of London UDK: 243.4:323(510)”1949/...” United Kingdom THE SECURITISATION OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract This article examines the troubled relationship between Tibetan Buddhism and the Chinese state since 1949. In the history of this relationship, a cyclical pattern of Chinese attempts, both violently assimilative and subtly corrosive, to control Tibetan Buddhism and a multifaceted Tibetan resistance to defend their religious heritage, will be revealed. This article will develop a security-based logic for that cyclical dynamic. For these purposes, a two-level analytical framework will be applied. First, the framework of the insecurity dilemma will be used to draw the broad outlines of the historical cycles of repression and resistance. However, the insecurity dilemma does not look inside the concept of security and it is not helpful to establish how Tibetan Buddhism became a security issue in the first place and continues to retain that status. The theory of securitisation is best suited to perform this analytical task. As such, the cycles of Chinese repression and Tibetan resistance fundamentally originate from the incessant securitisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese state and its apparatchiks. The paper also considers the why, how, and who of this securitisation, setting the stage for a future research project taking up the analytical effort to study the why, how and who of a potential desecuritisation of all things Tibetan, including Tibetan Buddhism, and its benefits for resolving the protracted Sino- Tibetan conflict. -

International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding

The Unintended Consequences of Democracy Promotion: International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anna M. Meyerrose, M.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Alexander Thompson, Co-Advisor Irfan Nooruddin, Co-Advisor Marcus Kurtz William Minozzi Sara Watson c Copyright by Anna M. Meyerrose 2019 Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, international organizations (IOs) have engaged in unprecedented levels of democracy promotion and are widely viewed as positive forces for democracy. However, this increased emphasis on democracy has more re- cently been accompanied by rampant illiberalism and a sharp rise in cases of demo- cratic backsliding in new democracies. What explains democratic backsliding in an age of unparalleled international support for democracy? Democratic backsliding oc- curs when elected officials weaken or erode democratic institutions and results in an illiberal or diminished form of democracy, rather than autocracy. This dissertation argues that IOs commonly associated with democracy promotion can support tran- sitions to democracy but unintentionally make democratic backsliding more likely in new democracies. Specifically, I identify three interrelated mechanisms linking IOs to democratic backsliding. These organizations neglect to support democratic insti- tutions other than executives and elections; they increase relative executive power; and they limit states’ domestic policy options via requirements for membership. Lim- ited policy options stunt the development of representative institutions and make it more difficult for leaders to govern. Unable to appeal to voters based on records of effective governance or policy alternatives, executives manipulate weak institutions to maintain power, thus increasing the likelihood of backsliding. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party - Introduction

(Updated on January 12, 2005) Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party - Introduction More than a decade after the fall of the former Soviet Union and Eastern European communist regimes, the international communist movement has been spurned worldwide. The demise of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is only a matter of time. Nevertheless, before its complete collapse, the CCP is trying to tie its fate to the Chinese nation, with its 5000 years of civilization. This is a disaster for the Chinese people. The Chinese people must now face the impending questions of how to view the CCP, how to evolve China into a society without the CCP, and how to pass The Epoch Times is now publishing a special editori al series, on the Chinese heritage. The Epoch Times is “Nine Commentaries on the Chinese Communist Party.” now publishing a special editorial series, “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party.” Before the lid is laid on the coffin of the CCP, we wish to pass a final judgment on it and on the international communist movement, which has been a scourge to humanity for over a century. Throughout its 80-plus years, everything the CCP has touched has been marred with lies, wars, famine, tyranny, massacre and terror. Traditional faiths and principles have been violently destroyed. Original ethical concepts and social structures have been disintegrated by force. Empathy, love and harmony among people have been twisted into struggle and hatred. Veneration and appreciation of the heaven and earth have been replaced by an arrogant desire to “fight with heaven and earth.” The result has been a total collapse of social, moral and ecological systems, and a profound crisis for the Chinese people, and indeed for humanity. -

SOCIALISM CANNOT BE BUILT in ALLIANCE with the BOURGEOISIE the Experience of the Revolutions in Albania and China Jim Washington, About 1980, USA

SOCIALISM CANNOT BE BUILT IN ALLIANCE WITH THE BOURGEOISIE The Experience of the Revolutions in Albania and China Jim Washington, about 1980, USA CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION 1 I CHINA 4 1 “New Democracy” 4 2 Four Classes in Power 6 3 Gradual and Peaceful Transition to Socialism 7 4 Liu Shao-chi and the Right Wing of the CPC 10 5 The Transformation of Industry and Commerce 13 6 The Eighth Congress of the CPC 15 7 The Decentralization of the Economy and the Wage Reform of 1956 18 8 The “Rectification” of the Party 21 9 “Contradictions Among the People” 23 II ALBANIA 26 1 The Democratic Revolution 26 2 Conciliation With or Expropriation and Suppression of the Bourgeoisie? 27 3 The Struggle Against the Titoite Revisionists 29 4 The Consolidation of Socialist Relations of Production 30 5 The Struggle Against the Soviet Revisionists 34 III THE PLA’S CRITIQUE OF “NEW DEMOCRACY” IS CORRECT 38 1 The Popularization of the Theory of “New Democracy” 38 2 Alliances with Sectors of the Bourgeoisie in National-Democratic Revolutions 39 3 The Nature of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat and the Class Struggle During 42 the Transition to Socialism IV INTRODUCTION TO PART TWO: CLASS STRUGGLE IN SOCIALIST 50 SOCIETY V LEARNING FROM THE CHINESE AND ALBANIAN EXPERIENCES 56 NOTES 58 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 INTRODUCTION The seizure of power in China by the Teng Hsiao-ping revisionist clique stunned the com- munist movement in our country. Some organizations displayed their opportunism and hastened to consolidate themselves around the increasingly open reactionary line of the Chinese Com- munist Party. -

Chinese Cultural Revolution

Chinese Cultural Revolution Background Guide Written by: Sruthi Venkatachalam and Patrick Lee, Case Western Reserve University The Rise of Modern China The reign of the Chinese dynasties ended in 1911 leading to China’s emergence into the modern world. China’s weakness in the 20th century, as seen in the devastating loss in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, stirred unrest and murmurs of uprising among the population. In 1911, armed rebellions broke out in response to the nationalization of railways in the Sichuan province, word of which spread across China. This snowballed and lead warlords to rebel against the weak imperial regime. Such rebellion in Wuchuan led to the overthrow of the provincial government and revolutionary leader Sun Yixian took advantage of the regime’s weakness. He later returned from exile, elected provisional president He saw that the emperor be abdicated, and resign power allowing Yuan Shikai, imperial minster entrusted with full power via the courts, to become the nation’s first president.1 In early 1912, the reign of Imperial China, Yuan Shikai’s attempt to become military dictator was thwarted and the Nationalist party, the Guomindang, also known as the Kuomintang (GMD) took control of the country in 1923. Sun Yixian, now president, reorganized the party that made it a centralized, democratic party. The GMD worked with the nearly formed Chinese Communist Party, with Soviet assistance, to reunite China and end the control of warlords running rampant in the 1 Wang, Yi Chu. “Sun Yat-sen : Chinese Leader.” n.d. Britannica. Accessed November 9. 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sun-Yat-sen country. -

Comrades-In-Arms: the Chinese Communist Party's Relations With

Cold War History ISSN: 1468-2745 (Print) 1743-7962 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcwh20 Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76 Joshua Eisenman To cite this article: Joshua Eisenman (2018): Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76, Cold War History To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2018.1440549 Published online: 20 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fcwh20 COLD WAR HISTORY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2018.1440549 Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76 Joshua Eisenman LBJ School of Public Affairs, the University of Texas at Austin, Austin, United States ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This study examines the evolution of the Chinese Communist China; Africa; Communism; Party’s (CCP) motives, objectives, and methods vis-à-vis its African Mao; Soviet Union counterparts during the Mao era, 1949–76. Beginning in the mid- 1950s, to oppose colonialism and US imperialism, the CCP created front groups to administer its political outreach in Africa. In the 1960s and 1970s, this strategy evolved to combat Soviet hegemony. Although these policy shifts are distinguished by changes in CCP methods and objectives towards Africa, they were motivated primarily by life-or- death intraparty struggles among rival political factions in Beijing and the party’s pursuit of external sources of regime legitimacy. -

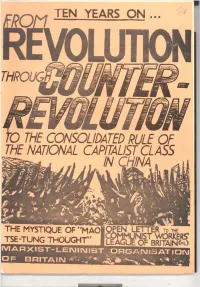

The Consolidated Rule of the National Capitalist Class in ~Na

TEN YEARS ON ... · THE CONSOLIDATED RULE OF THE NATIONAL CAPITALIST CLASS IN ~NA THE MYSTIQUE OF ''MAO _ __... TSE -TUNG THOUGHT'' I N T R 0 D U C T I 0 N THE HISTORY OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA SINCE 1966 HAS FULLY VINDICATED THE MLOBiS EXPOSuRE OF .THE COUNTER-REVOLUTIO~ARY "GREAT PROLETARIAN CULTURAL REVOLUTION" It is now almost 10 years since the Marxist-Leninist Organisation of Britain issued its historic "Report on the Situation in the People's Republic of China". This now classic analysis of the origins L s!e.yelopment and alignment of class forces in the "Great -Proletarian Cultural Revolution" of 1966-68 showed tha.b behind the demagogic mask of "socialism" in China lay: a tacTica_]J.y con:c;aled~apparatus of p ower through which- the chineE_e national- capitalist class could make its dictator ship effective in the specific conditions of a Chine. the workers and peasants of which had carried through, 17 years earlier ~ -a victu~ious national-democratic revol ution and whose revolutionary zeal and striving for fundamental social change remained at a high level. The objective situation ~n the newly-founded People's Republic of China in which, in the years immediately following the victory of the national-democratic revolution in 1949, the national capitalist class found itself, in which it was compelled to lay the first foundations of its economic system and to mould and strengthen its state apparatus of rule - the two together, base and superstructure, making up the system of "new democracy", the blueprint-for which was -

WORLD OUTLOOK PERSPECTIVE MONDIALE Un Service De Presse O Uv N ·E R -'-- ;__..-:'--...______

a labor press s~rvice WORLD OUTLOOK PERSPECTIVE MONDIALE Un service de presse _o_uv_n_·e_r_-'--_;__..-:'--...__ ______...... PARIS OFFICE: Pierre Frank, 21 rue d'Aboukir, Paris 2, France NEW YORK OFFICE: World Outlook, P. 0. Box 635, Madison Sq . Station, New York, N. Y. 10010 Vol. 5, No. 6 February 10, 1967 In this issue 100,000 Workers Demonstrate in .Madrid ____ _____ _ 137 Fascist Shoots Down Young Communist in London 139 .Mao's "Cultural Revolution" (Interview with Peng 140 War Hawks in Washington Eye Coni'lict in China __ ___ _______ _ 149 Clergymen Demonstrate against Johnson's War 149 Hugo Blanco Case: Campaign in Argentina for Hugo Blanco 150 Chilean Chamber of Deputies Intervenes in Behalf of Hugo Blanco 150 Pro-Cuban .Magazine in Chile Opens Campaign for Hugo Blanco 150 Labour l'1P' s Appeal for Clemency in Blanco Case ___________________________ _ 151 Solidarity Rally for Hugo Blanco in London -- by Charles van Gelderen 151 "Newsletter" Reports Appeals for Blanco _____ _________ __ _ 152 Andre Gunder Frank Speaks for Hugo Blanco at Toronto Rally -- by Ross Dowson 152 Guatemalan Guerrilla Movement Continues to Grow 153 The New U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearings by George Novack 154 Socialist Party Suffers Setback in Japanese Elections 155 Cultural Revolution Remolds Music in Ch ina 156 .Mao's Thought Proves Too Much for Night-Soil Collector 157 Chinese Transport Workers Overfulfill 1966 Plan 157 More about the Events in Shanghai ---- ---------- ---- ------ --- 158 Price of Rice in Saigon Jumps Thirty Percent __ ___ 159 War Crimes Team Give First Results of Inquiry in North Vietnam 160 Japanese War Crimes Team Reports Preliminary Findings 161 Sartre Invited to Speak at Antiwar Assembly in Toronto 162 From the Pickax to the Pen -- or, Progress of the "New Criticism" -- II -- by L. -

MARIANA RUPPRECHT ZABLONSKY.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ MARIANA RUPPRECHT ZABLONSKY O DISCURSO DA NAÇÃO SOMALI E A PROPAGANDA NACIONALISTA DURANTE O REGIME MILITAR (1969-1976) CURITIBA 2019 MARIANA RUPPRECHT ZABLONSKY O DISCURSO DA NAÇÃO SOMALI E A PROPAGANDA NACIONALISTA DURANTE O REGIME MILITAR (1969-1976) Dissertação apresentada ao curso de Pós- Graduação em História, Setor de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de mestre em História. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Hector Hernandez Rolando Guerra. CURITIBA 2019 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ERRATA Zablonsky, Mariana Rupprecht. O Discurso da nação somali e a propaganda nacionalista durante o regime militar (1969-1976). / Mariana Rupprecht Zablonsky. - Curitiba, 2019. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em História do Setor de Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Folha Linha Onde se lê Leia-se 04 04 (1969-1977) (1969-1976) Dedico esta dissertação aos meus avós que sempre estiveram presentes em minha vida e me ajudaram a trilhar este caminho. E a todos os Somalis espalhados pelo globo. AGRADECIMENTOS A pesquisa do mestrado tem duração de dois anos e nesta curta jornada devo muito aos meus amigos e a minha família. Agradeço imensamente o apoio psicológico e financeiro fornecido pelos meus pais, João e Adriana, que sempre acreditaram na minha capacidade de realizar uma pesquisa relevante. Agradeço a minha irmã Joana, a primeira mestre da família, que me incentivou a fazer a pesquisa e me mostrou que conhecimento é um das coisas mais relevantes da vida. Sou grata aos meus grandes amigos Eric, Thais, Andressa que estiveram ao meu lado para ouvir lamentações e me lembraram que ao fim eu me sentiria grata por esta jornada. -

Red Scarf Girl

A Facing History and Ourselves Study Guide Teaching RED SCARF GIRL Created to Accompany the Memoir Red Scarf Girl, by Ji-li Jiang A Facing History and Ourselves Study Guide Teaching RED SCARF GIRL Created to Accompany the Memoir Red Scarf Girl, by Ji-li Jiang Facing History and Ourselves is an international educational and professional development organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote the development of a more humane and informed citizenry. By studying the historical development of the Holocaust and other examples of genocide, students make the essential connection between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives. For more information about Facing History and Ourselves, please visit our website at www.facinghistory.org. The front cover illustration is a section from a propaganda poster created during the beginning of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1968), the same years Ji-li describes in her memoir. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China 1949, government and party officials used mass- produced posters as a way to promote nationalism and convey the values of the Communist Party. Propaganda posters were especially important during the Cultural Revolution, and this poster represents many dominant themes of this media: the glorification of Mao, the color red symbolizing China and the Chinese Communist Party, and the depiction of youth as foot-soldiers for the revolution. The slogan on the poster expresses a popular anthem of the era: Chairman Mao is the Reddest Reddest Red Sun in Our Hearts.