Canberra Bird Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whistler3 Frontcover

The Whistler is the occasionally issued journal of the Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. ISSN 1835-7385 The aims of the Hunter Bird Observers Club (HBOC), which is affiliated with Bird Observation and Conservation Australia, are: To encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat To encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity HBOC is administered by a Committee: Executive: Committee Members: President: Paul Baird Craig Anderson Vice-President: Grant Brosie Liz Crawford Secretary: Tom Clarke Ann Lindsey Treasurer: Rowley Smith Robert McDonald Ian Martin Mick Roderick Publication of The Whistler is supported by a Sub-committee: Mike Newman (Joint Editor) Harold Tarrant (Joint Editor) Liz Crawford (Production Manager) Chris Herbert (Cover design) Liz Huxtable Ann Lindsey Jenny Powers Mick Roderick Alan Stuart Authors wishing to submit manuscripts for consideration for publication should consult Instructions for Authors on page 61 and submit to the Editors: Mike Newman [email protected] and/or Harold Tarrant [email protected] Authors wishing to contribute articles of general bird and birdwatching news to the club newsletter, which has 6 issues per year, should submit to the Newsletter Editor: Liz Crawford [email protected] © Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Website: www.hboc.org.au Front cover: Australian Painted Snipe Rostratula australis – Photo: Ann Lindsey Back cover: Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva - Photo: Chris Herbert The Whistler is proudly supported by the Hunter-Central Rivers Catchment Management Authority Editorial The Whistler 3 (2009): i-ii The Whistler – Editorial The Editors are pleased to provide our members hopefully make good reading now, but will and other ornithological enthusiasts with the third certainly provide a useful point of reference for issue of the club’s emerging journal. -

A 'Slow Pace of Life' in Australian Old-Endemic Passerine Birds Is Not Accompanied by Low Basal Metabolic Rates

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2016 A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Claus Bech University of Wollongong Mark A. Chappell University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lee B. Astheimer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gustavo A. Londoño Universidad Icesi William A. Buttemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bech, Claus; Chappell, Mark A.; Astheimer, Lee B.; Londoño, Gustavo A.; and Buttemer, William A., "A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates" (2016). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3841. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3841 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Abstract Life history theory suggests that species experiencing high extrinsic mortality rates allocate more resources toward reproduction relative to self-maintenance and reach maturity earlier ('fast pace of life') than those having greater life expectancy and reproducing at a lower rate ('slow pace of life'). Among birds, many studies have shown that tropical species have a slower pace of life than temperate-breeding species. -

The Ecological Basis of Sensitivity of Brown Treecreepers to Habitat Fragmentation: a Preliminary Assessment

Biological Conservation 90 (1999) 13±20 The ecological basis of sensitivity of brown treecreepers to habitat fragmentation: a preliminary assessment Jerey R. Walters a,*, Hugh A. Ford b, Caren B. Cooper c aDepartment of Zoology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695-7617, USA bDepartment of Zoology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia cDepartment of Biology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061-0406, USA Received 4 April 1998; received in revised form 22 October 1998; accepted 5 January 1999 Abstract We attempted to identify the mechanisms responsible for adverse eects of habitat fragmentation on brown treecreepers (Cli- macteris picumnus) inhabiting eucalyptus woodland in northeastern New South Wales, Australia by comparing demography and foraging ecology of birds in highly fragmented and relatively unfragmented landscapes. In particular, we investigated three possi- bilities, disrupted dispersal due to patch isolation, reduced fecundity due to elevated nest predation, and reduced food availability due to habitat degradation. Nesting success was high in both highly fragmented and less fragmented habitat. Of ®rst nests, 88% were successful, and 60% of successful groups attempted a second brood. However, there were many more groups in the more fragmented habitat than in the less fragmented habitat that lacked a female for most or all of the breeding season, and thus did not attempt nesting (64% vs 13%). In both the more fragmented and the less fragmented habitat, both males and females spent about 70% of their time foraging and 65% of their foraging time on the ground. We reject reduced fecundity in fragmented habitat as an explanation of adverse eects of habitat fragmentation on brown treecreepers. -

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026 Prepared by: Infrastructure Services & Planning and Ecology Australia Contents Acknowledgments 4 A Vision for the Future 5 Introduction 6 Summary of state and extent of biodiversity in Greater Dandenong 7 Study area 7 Flora and fauna 9 Existing landscape habitat types 10 Key threats to local biodiversity values 12 Habitat assessments 15 Habitat connectivity for icon species 16 Community consultation and engagement 18 Biodiversity legislation considerations 20 Council strategies 22 Actions 23 Protection and enhancement of existing biodiversity values 24 Improving knowledge of biodiversity values 26 Facilitating and encouraging biodiversity conservation and enhancement on private land 27 Managing threatening processes 28 Community engagement and education 30 References 32 Tables Table 1 Summary of most common reasons why biodiversity is considered important from online survey and examples of comments provided 19 Table 2 Commonwealth and Victorian biodiversity legislation 20 Plates Plate 1 City of Greater Dandenong LGA and municipality study area, including surrounding areas of biodiversity significance. 8 Plate 2 Potential connectivity sites within Greater Dandenong for all five icon species 17 DRAFT City of Greater Dandenong Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 – 2026 ii Appendices Appendix 1 Vegetation coverage across the City of Greater Dandenong pre 1750 (left) and today (right). 34 Appendix 2 Fauna species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ....................................................................................................... 35 Appendix 3 Flora species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ...................................................................................................... -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

The Crimson Finch

PUBLISHED FOR BIRD LOVERS BY BIRD LOVERS life Aviarywww.aviarylife.com.au Issue 04/2015 $12.45 Incl. GST Australia The Red Strawberry Finch Crimson Finch Black-capped Lory One Week in Brazil The Red-breasted Goose ISSN 1832-3405 White-browed Woodswallow The Crimson Finch A Striking Little Aussie! Text by Glenn Johnson Photos by Julian Robinson www.flickr.com/photos/ozjulian/ Barbara Harris www.flickr.com/photos/12539790@N00/ Jon Irvine www.flickr.com/photos/33820263@N07/ and Aviarylife. Introduction he Crimson Finch Neochmia phaeton has Talways been one of the rarer Australian finches in captivity, and even more so since the white- the mid-late 1980’s, when the previously legal bellied. The trapping of wild finches in Australia was crown is dark prohibited across all states. They unfortunately brown, the back and have a bad reputation for being aggressive, wings are paler brown washed with red, the tail and this together with the fact that they is long, scarlet on top and black underneath. are reasonably expensive in comparison to The cheeks along with the entire under parts are many other finches, could well be a couple deep crimson, the flanks are spotted white, and of the main reasons as to why they are not so the centre of the belly is black in the nominate commonly kept. race and white for N. p. evangelinae, and the Description beak is red. Hens are duller, with black beaks. They are an elegant bird, generally standing There are two types of Crimson Finches, the very upright on the perch, and range from 120- black-bellied, which is the nominate form and 140mm in length. -

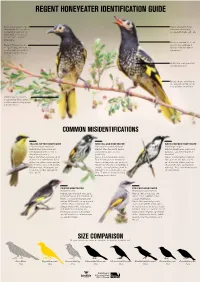

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Download Preprint

A continental measure of urbanness predicts avian response to local urbanization Corey T. Callaghan*1 (0000-0003-0415-2709), Richard E. Major1,2 (0000-0002-1334-9864), William K. Cornwell1,3 (0000-0003-4080-4073), Alistair G. B. Poore3 (0000-0002-3560- 3659), John H. Wilshire1, Mitchell B. Lyons1 (0000-0003-3960-3522) 1Centre for Ecosystem Science; School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences; UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 3Evolution and Ecology Research Centre; School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences; UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia *Corresponding author: [email protected] NOTE: This is a pre-print, and the final published version of this manuscript can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04863 Acknowledgements Funding for this work was provided by the Australian Wildlife Society. Mark Ley, Simon Gorta, and Max Breckenridge were instrumental in conducting surveys in the Blue Mountains. We also are grateful to the numerous volunteers who submit their data to eBird, and the dedicated team of reviewers who ensure the quality of the database. We thank the associate editor and two anonymous reviewers for comments that improved this manuscript. Author contributions CTC, WKC, JHW, and REM conceptualized the data processing to assign urban scores. CTC, MBL, and REM designed the study. CTC performed the data analysis with insight from WKC and AGBP. All authors contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. Data accessibility Code and data necessary to reproduce these analyses have been uploaded as supplementary material alongside this manuscript, and will be made available as a permanently archived Zenodo repository upon acceptance of the manuscript. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

Accepted Version

ACCEPTED VERSION Patrick L. Taggart Are blood haemoglobin concentrations a reliable indicator of parasitism and individual condition in New Holland honeyeaters (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae)? Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 2016; 140(1):17-27 © 2016 Royal Society of South Australia "This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia on 01 Mar 2016 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2016.1151970 PERMISSIONS http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/sharing-your-work/ Accepted Manuscript (AM) As a Taylor & Francis author, you can post your Accepted Manuscript (AM) on your personal website at any point after publication of your article (this includes posting to Facebook, Google groups, and LinkedIn, and linking from Twitter). To encourage citation of your work we recommend that you insert a link from your posted AM to the published article on Taylor & Francis Online with the following text: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in [JOURNAL TITLE] on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI].” For example: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Africa Review on 17/04/2014, available online:http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/12345678.1234.123456. N.B. Using a real DOI will form a link to the Version of Record on Taylor & Francis Online. The AM is defined by the National Information Standards Organization as: “The version of a journal article that has been accepted for publication in a journal.” This means the version that has been through peer review and been accepted by a journal editor. -

Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterraneanclimate Ecosystem

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit -- Staff Publications Unit 2002 Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterraneanclimate Ecosystem Craig R. Allen U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Denis A. Saunders Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ncfwrustaff Part of the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Allen, Craig R. and Saunders, Denis A., "Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterraneanclimate Ecosystem" (2002). Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit -- Staff Publications. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ncfwrustaff/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit -- Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Ecosystems (2002) 5: 348–359 DOI: 10.1007/s10021-001-0079-2 ECOSYSTEMS © 2002 Springer-Verlag Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterranean- climate Ecosystem Craig R. Allen1* and Denis A. Saunders2 1US Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, South Carolina Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, G27 Lehotsky, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634, USA; and 2CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, GPO Box 284, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia ABSTRACT Nomadism in animals is a response to resource dis- cance of the variables body mass and diet (nectar) tributions that are highly variable in time and space. may reflect the greater energy requirements of Using the avian fauna of the Mediterranean-climate large birds and the inherent variability of nectar as region of southcentral Australia, we tested a num- a food source. -

December 2016 Vol

Castlemaine Naturalist December 2016 Vol. 41.11 #449 Monthly newsletter of the Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club Inc. Powerful Owl chick - photo Noel Young Moths of Victoria – and Castlemaine CFNC members were fortunate to have Marilyn Hewish as guest speaker at the Club’s November meeting. Marilyn is a distinguished naturalist, who received the Australian Natural History Medallion in 2013 for her decades of work on Australian birds and her more recent contributions to studies of the moths of Victoria. She told us how she had become a “moth addict” and that most of the commonly stated ways to distinguish moths and butterflies are myths – some moths are active during daylight, many are highly coloured (not “brown and boring”), some have clubbed antennae. The technical difference is in the way the forewings and hindwings are linked – needing microscopic examination! Moths and their caterpillars play a major ecological role, for example as a significant food source for birds, bats, reptiles, small mammals and larger invertebrates. Some caterpillars feed on leaf litter, thus recycling nutrients and reducing the intensity of fires. Some day-flying moths pollinate flowers. Though butterflies are more familiar to most naturalists, they are far outnumbered by moth species in Australia: about 400 species of butterflies and more than 20,000 moths (the exact figure is not known). The studies of Victorian moths are in very early stages compared to our knowledge of Australian birds. Marilyn and Dean are frequently in the field – at night (even when cold and wet), surveying moths at sites across Victoria. They often record large extensions in distributions, species not previously known from the state, and even species new to science.