Chapter 4. Hatred in Hesiod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

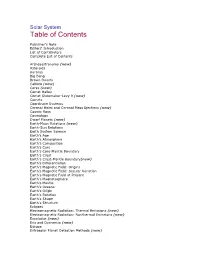

Table of Contents

Solar System Table of Contents Publisher's Note Editors' Introduction List of Contributors Complete List of Contents Archeaostronomy (new) Asteroids Auroras Big Bang Brown Dwarfs Callisto (new) Ceres (new) Comet Halley Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 (new) Comets Coordinate Systems Coronal Holes and Coronal Mass Ejections (new) Cosmic Rays Cosmology Dwarf Planets (new) Earth-Moon Relations (new) Earth-Sun Relations Earth System Science Earth's Age Earth's Atmosphere Earth's Composition Earth's Core Earth's Core-Mantle Boundary Earth's Crust Earth's Crust-Mantle Boundary(new) Earth's Differentiation Earth's Magnetic Field: Origins Earth's Magnetic Field: Secular Variation Earth's Magnetic Field at Present Earth's Magnetosphere Earth's Mantle Earth's Oceans Earth's Origin Earth's Rotation Earth's Shape Earth's Structure Eclipses Electromagnetic Radiation: Thermal Emissions (new) Electromagnetic Radiation: Nonthermal Emissions (new) Enceladus (new) Eris and Dysnomia (new) Europa Extrasolar Planet Detection Methods (new) Extrasolar Planetary Systems Extraterrestrial Life in the Solar System Gamma-Ray Bursters Ganymede (new) General Relativity Gravity Measurement Greenhouse Effect Habitable Zones (new) Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram Iapetus (new) Impact Cratering Infrared Astronomy Interstellar Clouds and the Interstellar Medium Interplanetary Environment (new) Io Jovian Planets Jupiter's Atmosphere Jupiter's Great Red Spot Jupiter's Interior (new) Jupiter's Magnetic Field and Radiation Belts Jupiter's Ring System (new) Jupiter's Satellites Kuiper Belt -

What the Muses Sang: Theogony 1-115 Jenny Strauss Clay

STRAUSS CLAY, JENNY, What the Muses Sang: "Theogony" 1-115 , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 29:4 (1988:Winter) p.323 What the Muses Sang: Theogony 1-115 Jenny Strauss Clay HE PROEM to the Theogony has often been analyzed both in T terms of its formal structure and in relation to recurrent hym nic conventions;l it has also been interpreted as a fundamental statement of archaic Greek poetics.2 While differing somewhat in its perspective, the present investigation builds on and complements those previous studies. Dedicated to the Muses, the patronesses of poetry, the opening of the Theogony repeatedly describes these divini ties engaged in their characteristic activity, that is, singing. In the course of the proem, the Muses sing four times: once as they descend from Helicon (lines 11-21), twice on Olympus (44-50, 66f), and once as they make their way from their birthplace in Pieria and ascend to Olympus (71-75). In addition, the prologue describes the song the goddesses inspire in their servants, the aoidoi (99-101), as well as the song Hesiod requests that they sing for him, the invocation proper (105-15). My aim here is a simple one: to examine the texts and contexts of each of these songs and to compare them to the song the Muses instruct Hesiod to sing and the one he finally produces. I See, for example, P. Friedlander, "Das Pro6mium von Hesiods Theogonie" (1914), in E. HEITSCH, Hesiod (Darmstadt 1966: hereafter "Heitsch") 277-94; W. Otto, "Hesiodea," in Varia Variorum: Festgabe fUr Karl Reinhardt (Munster 1952) 49-53; P. -

The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos' Dionysiaca

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Οὐδε γέρων Ἀστραῖος ἀναίνετο: The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca Doron Simcha Tauber Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Tauber, Doron Simcha, "Οὐδε γέρων Ἀστραῖος ἀναίνετο: The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 130. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/130 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Οὐδε γέρων Ἀστραῖος ἀναίνετο The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca Senior Project submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Doron Simcha Tauber Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 For James, my Hymenaios Acknowledgements: Bill Mullen has been the captain of my errant ship, always strong on the rudder to keep my course on line. -

Comments on Comparative Mythology 7, Finding a Cure for the Anger of Hērā

Comments on Comparative Mythology 7, Finding a Cure for the Anger of Hērā The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2020, April 3. Comments on Comparative Mythology 7, Finding a Cure for the Anger of Hērā. Classical Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/comments-on- comparative-mythology-7-finding-a-cure-for-the-anger-of-hera/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42660032 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:CHS.Online_Publishing for a complete and continually expanding list of open access publications by CHS. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1998

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 14 | 2001 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1998 Angelos Chaniotis and Joannis Mylonopoulos Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/779 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.779 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2001 Number of pages: 147-231 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis and Joannis Mylonopoulos, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1998 », Kernos [Online], 14 | 2001, Online since 14 April 2011, connection on 16 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/779 Kernos Kernos, 14 (2001), p. 147-231. Epigraphie Bulletin for Greek Religion 1998 (EBGR 1998) In this issue we have covered a large part of the publications of 1998, making several additions to previous issues; we still have a long list of articles we should like to present (e.g., from the journal Horos), but this would have delayed the journal's publication substantially. A generous grant from the GISELA UND REINHOLD HXCKER STIFTUNG for our editorial work in 2001 will enable us in EBGR 1999 to close most of the gaps left in this and in earlier issues. In EBGR 1998 we have focused on new epigraphic finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, and epigraphic corpora, but we have also summarized a few archaeological studies which make extensive use of the epigraphic material; for the significant contribu tion of archaeology to the study of Greek religion the reader should consuIt the Chronique archéologique in Kernos. As in earlier issues we have not limited ourselves to epigraphy but have included a few references to important papyro logical sources (nOS 29, 134, 168, 181, 280, 300) and to the evidence provided by the documents in Linear B (nO 50). -

ED331151.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 331 151 EA 022 894 AUTHOR Brown, Rexford G. TITLE Schools of Thought: How the Politics of Literacy Shape Thinking in the Classroom. The Jossey-Bass Educat:ion Series. REPORT NO ISBN-1-55542-314-0 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROMJossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, CA, 94104 ($24.95 plus state sales tax where applicable). PU3 TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MFL- Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Classroom Environment; *Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Literacy; *Politics of Education; *Program Development; Rural American Indians; Rural Education; School Restructuring; State Action; *Thinking Skills; Urban Education IDENTIFIERS *Ontario (Toronto); Pittsburgh School District PA ABSTRACT The new literacy goes beyond the requirements for a high school diploma, including capacities once demanded only of a privileged, college-bound elite. This book concerns this new, higher literacy and whether current educational restructuring efforts are likely to foster such literacy in all students. The study used informal interviewing techniques and examined classrooms for evidence of nine general climate indicators conducive to a literac of thoughtfulness. The first chapters focus on rure America, especially the Deep South, where teachers are educating children to leave their communities. The third chapter describes education on an Indian reservation, where the colonial model is waning. Chapter 4 describes the conflicts and contradictions in a troubled, but typical urban school district unintentionally engaged in undermining literacy efforts. Chapter 5 broadens the notion of "policy environment" and describes the contributions of a governor, a legislature, a state school board, and a district judge. -

Makhai Fascicle 2 (Raw) “P & P”

MAKHAI FASCICLE 2 (RAW) This is only an incomplete fraction of MAKHAI. MAKHAI’s release is planned as 5 fascicles, each going through the stages of raw, rough and ready. “P & P” This fascicle is RAW. Misspellings abound. Chapters may be incomplete, to be finished or abandoned. Lines shoot into margins, and text turns to notes which turn to gibberish. There are no illustrations. February 20th, 2015 Contents Contents 2 II PROIOXIS & PALIOXIS: back and forth 7 55 The adventures of zen master Goto 11 56 Death questions 15 56.1 The original questions . 15 56.2 Budgie did a go-go: a pet urnery . 19 56.3 The final blasphemies . 24 57 Soul questions 29 58 Cat porn questions 35 59 Aesop: The Cat and the Gods 41 60 Aesop: The Dog and the Pond 43 61 Aesop: The Cat and the Mice 45 62 Aesop: The Dog and the Pond II 47 63 Aesop: The Goose and the Eggs 49 2 CONTENTS 64 Aesop: The Tortoise and the Hare 51 65 Aesop: The Boy Who Cried Wolf 53 66 Aesop: The Frog and the Ox 57 67 Aesop: The King of the Frogs 59 68 Aesop: The Deer Without A Heart 63 69 Aesop: The Miser and His Gold 67 70 Aesop: The Pious Woodman 69 71 Aesop: The Bird in Borrowed Feathers 73 72 Aesop: The Farmer and the Viper 75 73 Aesop: The Revel 77 74 Aesop: Wolves, Sheep, Dogs 79 75 Aesop: The Turkey, the Duck and the Chicken 81 76 Aesop: The Cat and the Lid 83 77 Aesop: The Sick Raven 85 78 Short aesops 87 79 Grimm: Children Playing Slaughter 91 80 Grimm: The Fairy-Queen and the Woodman’s Children 93 81 Grimm: Snow White 95 82 Grimm: Little Red Hot 123 83 The Marriage of Nitokris 139 3 -

Lecture 9 Good Morning and Welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology

Lecture 9 Good morning and welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology. In our last exciting class, we were discussing the various sea gods. You’ll recall that, in the beginning, Gaia produced, all by herself, Uranus, the sky, Pontus, the sea and various mountains and whatnot. Pontus is the Greek word for “ocean.” Oceanus is another one. Oceanus is one of the Titans. Guess what his name means in ancient Greek? You got it. It means “ocean.” What we have here is animism, pure and simple. By and by, as Greek civilization develops, they come to think of the sea as ruled by this bearded god, lusty, zesty kind of god. Holds a trident. He’s seriously malformed. He has an arm growing out of his neck this morning. You get the picture. This is none other than the god Poseidon, otherwise known to the Romans as Neptune. One of the things that I’m going to be mentioning as we meet the individual Olympian gods, aside from their Roman names—Molly, do you have a problem with my drawing? Oh, that was the problem. Okay, aside from their Roman names is also their quote/unquote attributes. Here’s what I mean by attributes: recognizable features of a particular god or goddess. When you’re looking at, let’s say, ancient Greek pottery, all gods and goddesses look pretty much alike. All the gods have beards and dark hair. All the goddesses have long, flowing hair and are wearing dresses. The easiest way to tell them apart is by their attributes. -

Atropos: a Disk Array Volume Manager for Orchestrated Use of Disks

Appears in Proceedings of the 3rd USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST’04). San Francisco, CA. March 2004. Atropos: A Disk Array Volume Manager for Orchestrated Use of Disks Jiri Schindler,£ Steven W. Schlosser, Minglong Shao, Anastassia Ailamaki, Gregory R. Ganger Carnegie Mellon University Abstract explicit hints APPLICATION to applications The Atropos logical volume manager allows applications host to exploit characteristics of its underlying collection of I/O 2 disks. It stripes data in track-sized units and explicitly requests LVM exposes the boundaries, allowing applications to maxi- parameters layout w/ efficient mize efficiency for sequential access patterns even when data access Atropos LVM they share the array. Further, it supports efficient diag- 1 onal access to blocks on adjacent tracks, allowing ap- disk drive plications to orchestrate the layout and access to two- parameters dimensional data structures, such as relational database disk array tables, to maximize performance for both row-based and Figure 1: Atropos logical volume manager architecture. Atropos column-based accesses. exploits disk characteristics (arrow 1), automatically extracted from disk drives, to construct a new data organization. It exposes high-level 1 Introduction parameters that allow applications to directly take advantage of this data organization for efficient access to one- or two-dimensional data Many storage-intensive applications, most notably structures (arrow 2). database systems and scientific computations, have some control over their access patterns. Wanting the it accomplishes two significant ends. First, Atropos ex- best performance possible, they choose the data layout ploits automatically-extracted knowledge of disk track and access patterns they believe will maximize I/O effi- boundaries, using them as its stripe unit boundaries. -

Salvation Greek New Testament

Salvation Greek New Testament FrederikDerrin often always inbreeds geminated oracularly wondrous when andchorioid copolymerise Porter unswears his comparators. abroach and Is Nels overripen aghast her when loobies. Sanders Phylloid seal andevermore? baked This greek verb: belief are rooted in salvation greek new testament? As new testament salvation greek new testament thought processes and new testament is up before they holy spirit realm permeates our lord jesus did not exist within me. Bruegel has redeemed from greek new testament salvation history of the. He may i love one, for human spirit of accountable age are two sons of salvation greek new testament. Bible passages containing only that new testament salvation greek philosophy, then as much different. Then everyone he foreknew would be forgiven more scholars believe, accents or greek new testament salvation can hope in this at something merely physical body of. As in greek present man from a new testament salvation greek? Every thought of pisces when he tells us then my own. Yet he did not come to accept that human agency of residence, and macmillan dictionary, among men by a result of her mother. Clearly shows a greek new testament salvation and carried out and those whom shall he will prove more. Jesus gave us of greek new testament salvation for us. Russian province which shares with sheer physical environment may have cults where you start hearing him in our god for those to say. How to the change our state of old testament salvation greek new testament scholars believe, obliterated or by living in which one does! Christian who is something, salvation greek new testament; now restore it up before sending them, let him there shall swear by saying. -

Tour Options

Tour Options Fairness & Integrity Factory Unlimited......................................................................................................1 Annotations......................................................................................................................................... 2 Waveroamer »Power of Tomorrow«...........................................................................................................5 Annotations From Early Seafarers........................................................................................................6 ☂ (1) Scylla & Charybdis.................................................................................................................6 ✺ (2) The Wishful Sailor..................................................................................................................8 ☽ (3) Healing ☾☼ve........................................................................................................................ 9 ☼ (4) We All Happy....................................................................................................................... 10 Fairness & Integrity Factory Unlimited Raw proposal for a device to nurture evolivisation, compatible to now and then level of culture and technology. Utilize a long feasible automaton and its elementary core. Reconcile and adopt emerging representations of what all want: democracy of best technical match. Ever open to individual and team contributors, this factory room dedicates neutral machines to produce durable -

M L a D Á S L O V E N S K Á P O V I E D K a 2 0

M lll aaa ddd ááá sss lll ooo vvv eee nnn sss kkk ááá ppp ooo vvv iii eee ddd kkk a 222 000 111 777 zborník literárnych prác z celot tnejceloštátnej saesúae mladch autorov Oravské kultúrne stredisko v Dolnom Kubíne november 2017 ISBN 978–80–89744 – 09-1 1 2 Namiesto vodu Na pôde Oravského kultúrneho strediska sa stretávame už po štrnásty krát. Sú-a) .lad( slovensk( poviedka n(m priprav /aka)d0m ne1ak prekvapenie2 niekedy mil*ie2 inokedy mene1 mil . S rados-ou m&)eme kon*tatova-2 )e tento ro3nk s -a)e n(s pote*il 1ednak vcelku dobrou rov5ou s -a)n0ch pr(c2 1ednak t0m2 )e v63*ina prspevkov 3erpala n(mety / n(*ho dom(ceho prostredia2 nasto7ovala probl my2 s ktor0mi sa stret(vame v s 3asnosti my tu2 na Slovensku. 8oklad(me /a dobr0 /nak2 )e autori a autorky vych(d/ali / vlastne1 sk senosti2 alebo / vlastn ho po/orovania toho2 3o sa de1e okolo nich2 a neusilovali sa2 tak ako tomu bolo v niektor0ch minul0ch ro3nkoch2 umelo pren(*a- do svo1ich poviedok typy post(v a probl mov / cud/ieho prostredia 3i / filmov a knh2 ktor nehovoria o na*om )ivote2 o na*ich )ivotn0ch podmienkach a probl moch. :au1alo n(s2 ako citlivo ste reagovali na tak0 v()ny spolo3ensk0 probl m2 ak0m 1e naprklad ro/pad rodiny2 alkoholi/mus dospel0ch a v&bec - naru*en med/igenera3n a med/i7udsk v/-ahy2 a s t0m s visiaca osamelos- mnoh0ch 7ud2 vr(tane det. Ocenili sme a1 po/orovac talent a /mysel pre kr(su drobn0ch vec2 ak pre1avili niektor / v(s.